|

HOPEWELL FURNACE

Guidebook 1940 |

|

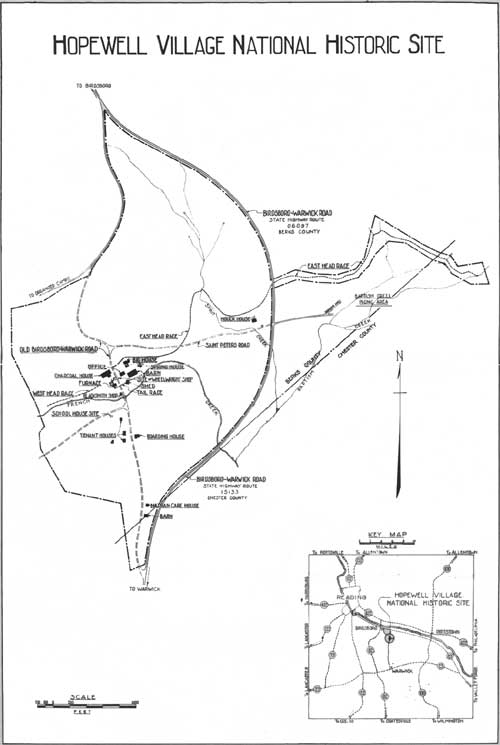

HOPEWELL VILLAGE NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE

Pennsylvania

Hopewell Village National Historic Site, six miles southeast of Birdsboro, Pennsylvania, in the Reading district of Berks County, contains 214 acres embracing the remains of a typical early American iron-making community. It was established in August 1938 as a unit of the National Park Service, United States Department of the Interior. Surrounding the site is the French Creek Recreational Demonstration Area, nearly 6,000 mores in extent, where picnic grounds, organized camps, and other public use facilities have been developed by the National Park Service.

THE EARLY AMERICAN IRON INDUSTRY

Like many ether now gigantic industries, the iron and steel industry of modern America had humble pioneer beginnings. One of its early centers was the Schuylkill Valley of Pennsylvania. where extensive resources of limestone, iron ore, water power and timber for the making of charcoal (all necessary in the cold-blast process of iron manufacture) were found within easy reach of navigable rivers and streams. In this region, near Pottstown. Pennsylvania's first bloomery forge was built in 1716, and three or four years later the first furnace. Colebrookdale, began operations. Two men Thomas Rutter and Thomas Potts, led the way in these enterprises, and others soon followed; by 1771 there were sore than 50 iron forges operating in the vicinity.

Among the far-seeing men whose imaginations were fired with the idea of building an American iron empire was William Bird, an English youth who came to Pennsylvania in the early eighteenth century. Working as a wood chopper for Rutter in 1733, he saved his money and finally went into business for himself. He acquired extensive lands west of the Schuylkill River near Hay Creek, built the first Birdsboro Forge there in 1740, and three years later began the construction of Hopewell Forge at or near the present Hopewell Furnace site. By 1756 his land holdings had grown to about 3,000 acres, he had built the mansion which still stands in Birdsboro, and his position as an important figure in the social, political, and economic life of eastern Pennsylvania was secure.

When William Bird died in 1761, his son Mark inherited the family business, which he soon expanded. The following year he went into partnership with George Ross. a prominent Lancaster lawyer, and together they built Mary Ann Furnace, the first iron furnace west of the Susquehanna River. Then, apparently dismantling or abandoning his father's earlier Hopewell Forge, Bird erected Hopewell Furnace on French Creek, along the old Birdsboro-Warwick Road.

The new furnace became the nucleus of Hopewell Village, a small, semifeudal settlement of colliers, teamsters, wheelwrights, moulders, blacksmiths, wood choppers, and other workers. Most of these employees lived in tenant houses built at the ironmaster's expense, while Bird or his manager at Hopewell occupied the so-called Big House, adjoining the group of smaller dwellings. A common store, tenant gardens, and nearby farms operated by the Bird family supplied all ordinary economic wants. Wagons and other necessary equipment were constructed or repaired in the Hopewell shops, and the farm animals and mules used for hauling purposes were stabled in the community barns. There was even a school for the village children.

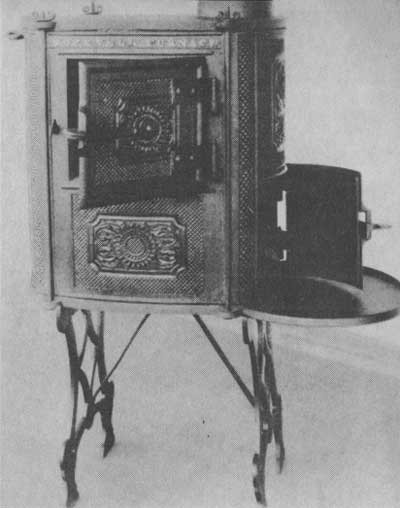

A Hopewell Ten-Plate Stove.

Nearly all the early Pennsylvania furnaces, Hopewell included, cast stoves and hollow ware, such as pots and kettles, in addition to manufacturing pig iron. The first stove castings were flat plates of iron with tulips, hearts, Biblical figures, and mottoes as decorations. One old stove marked "Hopewell Furnace" can still be seen at the historic site, while other representative castings are in the collections of the Historical Society of Berks County in Reading and of the Berks County Historical Society in Doylestown, Pennsylvania.

With the outbreak of the Revolutionary War, peacetime manufacturing at Hopewell gave way to the production of war materials. Mark Bird himself rendered active military service in the patriot cause. In August 1776 he fitted out 300 men of the Second Battalion, Berks County militia, at his own expense; later he went to Washington's aid after the Battle of Brandywine, September 11, 1777. The papers of the Continental Congress show that he also supplied large quantities of food and Hopewell iron to the United States Government, and that in so doing he ran heavily into debt. Bird's efforts to collect even part payment were apparently fruitless. A flood on Hay Creek added to the ruin of his property, and currency depreciation struck the final blow, Hopewell Furnace was finally advertised for sheriff's sale in April 1788, and at about the same time Bird moved to North Carolina where he died in comparative poverty. The Furnace lands were acquired in 1800 by Daniel Buckley and Thomas and Matthew Brooke, and from that time were owned and operated by the Brooks family until their transfer to the Federal Government.

Except for a few intermittent periods, Hopewell Furnace remained in operation until June 1883, when it was blown out for the last time. It was never converted to the hot-blast process, which came into almost universal use after 1850 and inaugurated a new era in the iron industry. Castings continued to be made at the Village until 1840, when the patterns were sold. After this, nearly all Hopewell pig iron, about 1.200 tons annually, went to various forges in Pennsylvania, bringing prices ranging from $28 to $45 a ton, except in 1864, when Civil War demand shot the price up to $99. A. Whitney & Sons, the Philadelphia carwheel manufacturers, contracted for the entire Furnace output from 1870 to 1883; it is therefore probable that Hopewell iron has rolled over several of the nation's transcontinental railroads.

This was the residence of Hopewell ironmasters and their families.

After 1883, when the making of cold-blast charcoal iron ceased to be profitable and the works closed down, the adjoining woodland continued to make good returns for several years. The active days of Hopewell Village were over, however, symbolizing in their passing the end of a long and picturesque period in the history of the iron industry, yielding to newer and more effective techniques.

THE RESTORATION PLAN

Long years of inactivity and neglect have left their mark on Hopewell Village. The bridge house, wheelwright shop. and wheel house are gone, together with the old schoolhouse which once stood on the road to Joanna Furnace. Still preserved, however, are the Furnace stack, the Big House and several of its outbuildings, the charcoal house, the blacksmith shop, a few of the old tenant houses, and the now dismantled water wheel and blast machinery, last used in 1883. The raceways which carried water to and from the Furnace are also in evidence.

Old Tenant House at Hopewell

Gradual restoration of Hopewell Village is contemplated by the National Park Service, although much historical, architectural, and archeological research remains to be done before all details are decided upon. It is hoped, however, that water will eventually run through the races again, turn the Furnace wheel, and thus operate the reproduced blast machinery. Restoration of other remaining and once existing buildings is planned to follow. Old-fashioned flowers and vegetables may be cultivated once more in the Village gardens, and the blacksmith shop, where much of the original equipment is still in place, will ring anew with the activities of hearth and anvil.

HOW TO REACH THE HISTORIC SITE

Hopewell Village National Historic Site is accessible from the north via U. S. Route 422. State Route 82, and county road. From the south it is reached over State Route 23 and county road. There is a station of the Reading Railroad at Birdsboro, where connections may be made with trains of the Pennsylvania Railroad.

Charcoal Burners at Work

FACILITIES FOR VISITORS

Guide service for visitors is furnished, covering the most important points of interest in the historic site. Picnic grounds are available in the adjoining French Creek Recreational Demonstration Area, where there are also facilities for swimming, hiking, riding, fishing, and camping.

ADMINISTRATION

Hopewell Village is under the jurisdiction of the National Park Service, United States Department of the Interior. Communications and inquiries should be addressed to the Superintendent, Hopewell Village National Historic Site, Birdsboro, Pennsylvania.

June 1940

HOPEWELL VILLAGE NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE

(click on image for a PDF version)

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> |

1940/hofu/sec1.htm

Last Updated: 20-Jun-2010