|

COLORADO

Guidebook 1964 |

|

". . . ever the land and sea are changing; old

lands are buried, and new lands are born."

. . . John Wesley Powell.

COLORADO NATIONAL MONUMENT

In west-central Colorado, nature for eons has been sculpturing a gigantic and fantastic landscape.

Here, the Uncompahgre Highland, a great upwarp in the earth's crust, has been worn down by erosion—the same forces that are wearing down all the great mountains of today. As the highland eroded away, streams and winds carried sediments into the lowlands or seas on either side.

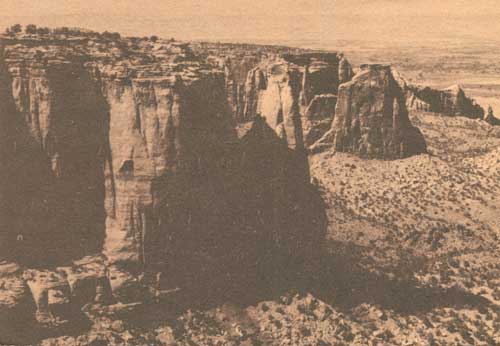

It was this slow, steady cutting, plus persistent erosion by rain, frost action, and wind, that gave us the corridorlike canyons lined with sheer cliffs, the towering monoliths, and the weird rock formations.

In the process, dinosaur bones over a hundred million years old have been exposed, petrified logs laid bare, and colorful stones washed out. Evidences of prehistoric Indians have been found on the canyon floors.

The numerous steep-walled canyons and sparsely distributed springs have helped to determine the present habitat and environment of many plants and animals. A pinyon pine-Utah juniper forest provides homes for many large and small mammals as well as for many species of birds and reptiles.

So outstanding is this area scenically and geologically that it has been set aside as Colorado National Monument.

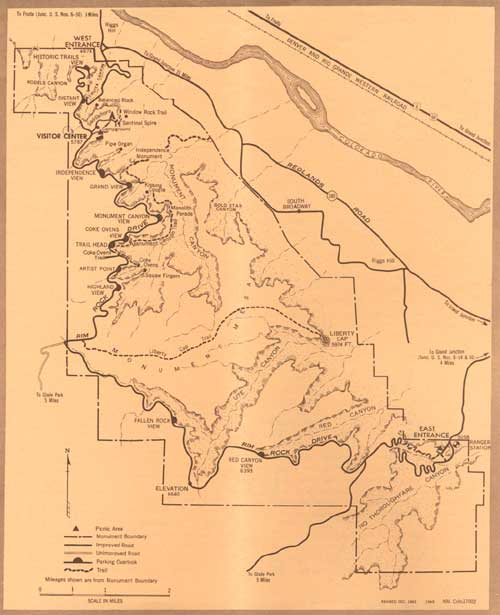

Balanced Rock, Coke Ovens, Sentinel Spire, Independence Monument, and Window Rock are but a few of the features you can see along 22-mile Rim Rock Drive, which skirts the walls of Red, Ute, No Thoroughfare, and Monument Canyons. To the north and northeast, the Book Cliffs form the skyline and mark the north side of Grand Valley. Grand Mesa looms to the eastward.

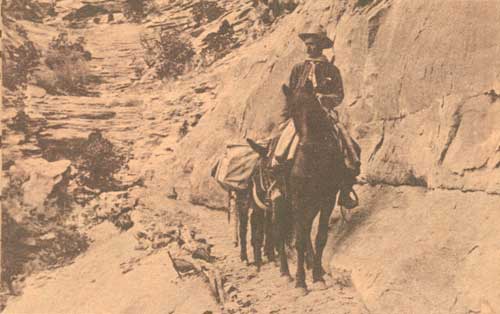

John Otto on one of his many trails in Colorado National Monument. From a print in the National Archives |

View down Monument Canyon from the road. |

ABOUT YOUR VISIT

The monument is 4 miles west of Grand Junction and 3-1/2 miles south of Fruita, Colo. Frontier and United Airlines and the Denver and Rio Grande Western Railroad serve Grand Junction. Continental Trailways buses serve both towns and the monument.

Special sightseeing trips are scheduled in summer from Grand Junction; for information, write Grand Junction and Fruita chambers of commerce. Cars may be rented at Grand Junction.

The monument is easily accessible by highway: U.S. 6, 24, 50 to Grand Junction; and U.S. 6 and 50 to Fruita.

At the Saddlehorn is a campground (no reservations) and picnic area, with tables, fireplaces, water, firewood, and toilets. Near the east entrance is a picnic area with shelter, restrooms, charcoal grills, and tables. Food, gasoline, and camping supplies are not available in the monument. There are accommodations in Grand Junction and Fruita.

In the visitor center, open all year, exhibits explain the prehistory, history, and natural history of the monument.

Window Rock and Coke Ovens Self-guiding Trails provide short, enjoyable walks along the canyon rims. Leaflets explain trailside features. Liberty Cap and Monument Canyon Trails are longer. Before taking the longer trails, tell a ranger at monument headquarters your hiking plans. In summer, be sure to take water.

HELP PROTECT YOUR MONUMENT

Natural features—Picking, disturbing, or damaging flowers, trees, or other plants, or removing rocks, minerals, or any other things native to the monument is prohibited.

Defacing signs, buildings, or other structures is illegal.

Fires are permitted only in campground fireplaces. Use—sparingly!—only wood prepared and placed there. You must obtain permission from the chief ranger's office to build fires elsewhere. Put your campfire OUT before you leave it.

Litter. Put refuse in the cans provided.

Do not throw or roll rocks or other objects into the canyons. This practice is destructive to the monument's natural beauty and endangers persons below.

Never hike or climb alone. If you plan to hike on Liberty Cap or Serpent Trail, tell someone where you are going and when you will return. Check with a ranger on trail conditions.

Pets are not allowed in the visitor center and must be under physical control at all times.

Maximum speed on the monument road is 35 miles per hour. Reduce speed on sharp and blind curves. Please do not park on or off the roadway—use use turnouts provided. Drive carefully.

Hunting is not allowed within monument boundaries. Firearms must be cased, broken down, or sealed to prevent their use.

(click on image for a PDF version)

THE MONUMENT'S GEOLOGY

Moisture and frost action, loss of cementing agents between sandstone grains, temperature variations, the work of floodwaters after heavy thunderstorms, and, above all, sapping or undercutting have formed these canyon landscapes.

At Colorado National Monument, you can stand at a number of points and see fine examples of rocks of many eras of geological time—from the ancient rocks of the Precambrian (over a billion years old) to the lava flows capping Grand Mesa, east of the monument, which were erupted less than a million years ago.

The core of the Uncompahgre Highland was composed of crystalline rock—granite, gneiss, schist, and pegmatite dikes—belonging to the Precambrian. Hundreds of millions of years elapsed as the highland eroded away. During this period, its surface was covered alternately with stream and lake deposits and with dunes of windblown sand. Then, at about the time the Rocky Mountains were being formed, tremendous earth forces lifted the Uncompahgre Plateau above the surrounding country.

Small canyons began to take form. Undermining of softer sections of sandstone layers caused them to break off continually, thus deepening and widening the canyons. As weathering continued, the thin ridges were cut through, and fractures or joints widened, leaving isolated columns of rocks or monoliths such as Independence Monument.

Great rock displacements, associated with the mountain-making uplifts in the Rocky Mountain region, cracked the crust of the earth to form a 10-mile-long fault. Today this forms a conspicuous escarpment, hundreds of feet high, that crosses the monument and constitutes one of its more spectacular features.

Rapid runoff from each summer shower pushes more mud and sand down the Colorado River drainage toward the sea. During the ice age the rainfall was probably much heavier than today's average of about 11 inches annually. The Colorado River must have been a much more formidable stream than it is now when it drained the many melting glaciers of the mountains to the east.

Nonetheless, despite today's aridity, Nature is removing rock, grain by grain, and is still carving the fantastic monoliths, open caves, and other forms that characterize Colorado National Monument.

PREHISTORY AND HISTORY

The artifacts, burials, and habitations found throughout most of the Southwest indicate that prehistoric basket-makers once lived in the area that includes Colorado National Monument.

The Ute Indians were the more modern inhabitants of this area. They occupied western Colorado when the white man first appeared.

Fray Francisco Atanasio Dominguez, accompanied by Fray Silvestro Velez de Escalante and nine others, five of whom were soldiers, representing the authority of Spain, set out from Santa Fe for Monterey, Calif., on July 29, 1776. According to Escalante's journal, the party passed north of the site of the present monument about August 27.

Antoine Robidoux, a Frenchman from St. Louis, established a trappers' supply and Indian trading post in the 1830's near the site of present-day Delta, Colo. (about 60 miles south of the monument). Unquestionably many trappers, including the famous Kit Carson, who visited Fort Robidoux, passed by what is now Colorado National Monument.

The modern story of the monument starts around the turn of the century when John Otto, a wanderer and visionary, settled in Monument Canyon.

Otto was a trailblazer who built roads and trails throughout the area. Not satisfied with his private enjoyment of the beauties of the red-and-tan canyon walls, he turned to publicizing them—by writing letters to interest people in setting aside the scenic area for the public. By 1907, he had aroused sufficient interest for a petition to be drawn up asking the Secretary of the Interior to consider preserving the area as a public park.

Otto's dreams came true; on May 24, 1911, President William Howard Taft signed a proclamation establishing the monument. Otto was named its first custodian.

FLORA AND FAUNA

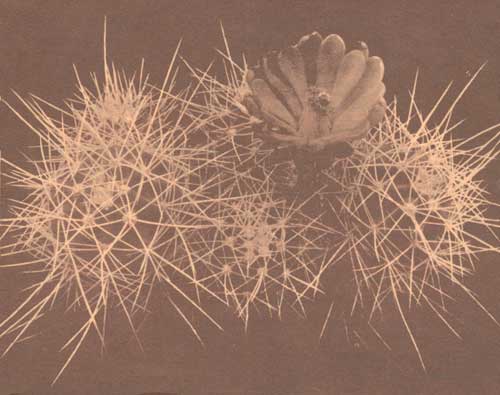

Wildflowers dot early spring and late summer landscapes; bright cactus blossoms and creamy spikes of yucca are particularly conspicuous. The forest cover is chiefly Utah juniper and pinyon pine, interspersed with such brushy and shrubby plants as sagebrush, serviceberry, and mountain-mahogany.

The monument is a wildlife sanctuary; deer, foxes, and bobcats are plentiful, and American elk are seen occasionally. Birds of many species are frequently seen.

As you drive through the pinyon pine-juniper forest, you will notice that many pinyons have been damaged by porcupines. The inner bark is eaten by "porky" when winter snows cover low-growing plants on which he normally feeds.

The clown of the monument's animal family is the ring-tail. Nocturnal in habit, it feeds on small rodents, birds, insects, and fruits. It is, surprisingly, unafraid of people, and puts on occasional nighttime shows along Rim Rock Drive.

In 1926, three bison were transplanted from the Denver Mountain Parks. The herd, now maintained at about 15 head because of the sparseness of forage, are occasionally seen in the canyons from Rim Rock Drive or from Redlands Road, grazing along the base of the escarpment.

ADMINISTRATION

Colorado National Monument, 28 square miles in area, is administered by the National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior.

The National Park System, of which this area is a unit, is dedicated to conserving the scenic, scientific, and historic heritage of the United States for the benefit and enjoyment of its people.

Development of this area is part of Mission 66, a dynamic conservation program designed to unfold the full potential of the National Park System for the use and enjoyment of present and future generations.

A superintendent, whose address is Box 438, Fruita, Colo., is in immediate charge of the monument.

AMERICA'S NATURAL RESOURCES

Created in 1849, the Department of the Interior—America's Department of Natural Resources—is concerned with the management, conservation, and development of the Nation's water, wildlife, mineral, forest and park and recreational resources. It also has major responsibilities for Indian and territorial affairs.

As the Nation's principal conservation agency, the Department works to assure that nonrenewable resources are developed and used wisely, that park and recreational resources make their full contribution to the progress, prosperity, and security of the United States—now and in the future.

VISITOR-USE FEES

Fees for 15-day or annual permits are collected for each vehicle entering the monument. During its valid period, the cost of the 15-day permit may be applied toward the annual permit.

All fees are deposited as revenue in the U.S. Treasury and offset, in part, the cost of operating the monument.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> |

1964/colm/sec1.htm

Last Updated: 20-Jun-2010