|

Capitol Reef

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER 15:

MINING AND RELATED

ENCROACHMENTS AT CAPITOL REEF NATIONAL PARK (continued)

Mining Regulations And The End Of Claims

Within Capitol Reef

As shown by the cases presented above, the National Park Service historically has not had as much control over mining within its units as one might assume. In fact, prior to the 1976 Mining in the Parks Act, the Bureau of Land Management actually controlled all mining claims on the public lands subject to the antiquated Mining Act of 1872. [106]

Virtually every national park and monument, including Capitol Reef, has been created subject to continuance of valid, existing rights. This stipulation meant that those holding valid, existing mining claims and oil and gas leases could continue working, and that the park or monument had virtually no say in the matter. This fact, together with the lenient regulations of the 1872 Mining Act, allowed uranium mining to proceed within Capitol Reef National Monument during the 1950s. It also enabled owners of the Tappan, Rainy Day, and other unpatented claims to continue blasting, mining, and making road improvements even after Congress created a national park in the area.

The Hard Rock Mining Act of 1872 was passed to legitimize previous claims and stimulate new mining operations on public lands. Under this act, a person could stake a claim, both on the ground and by filling out a one page application in the county recorder's office. An individual claim encompassed 20 acres, but the number of claims a person could acquire was unlimited. A group of up to eight individuals could create an association and claim up to 160 acres. These claims are called "unpatented" because the surface of the land was still owned by the federal government, but the claimant could pretty much do what he wanted on the property: build a home, divert water, cut timber, or graze livestock, for instance. The courts and federal agencies have been continually lenient in this regard. [107] Fortunately for Capitol Reef, the mining claims were on fairly inhospitable lands, which made continued occupation of the site undesirable.

The key to maintaining any mining claim under the 1872 act was to make a "discovery" of a valuable mineral deposit, and prove $100 worth of assessment work every year. Of course, the term "valuable" is open to broad interpretation, with the result that nullification proceedings can be dragged through years of appeals. The annual $100 assessment in 1872 constituted a substantial investment, but is virtually nothing now. Renting a caterpillar tractor and blading the road into the mine once a year could easily cost the required $100. Thus, so long as the claimant could prove a "discovery of valuable minerals" prior to acquisition of the land by the National Park Service, and so long as he kept up with the required assessment work, there was little the agency could do to nullify the existing claim. [108]

The situation changed in 1976 with passage of the Mining in the Parks Act. [109] As part of the 1970s federal land reform movement (which also saw passage of the National Environmental Policy Act and the Federal Land Policy and Management Act), the Mining in the Parks Act sought to give National Park Service officials tighter control over mining within parks and monuments. [110] The act requires claim holders to register all active claims, provide a detailed plan of operation for park manager approval, and purchase a substantial performance bond that must cover all reclamation costs. The law also prohibits new claims in any national park or monument. National recreation areas, however, are specifically exempted from these provisions. [111] Plans of operation and performance bond requirements have been used to prevent work on the Rainy Day mines, and similar requirements were used previous to the 1976 act to challenge Clair Bird's ripple rock operation.

While it could be argued that the 1976 Mining in the Parks Act was not strict enough, especially toward privately owned or patented claims, this act has proven to be a useful tool for National Park Service managers trying to prohibit mining within their parks. [112] One of the most useful aspects was the law's stipulation that all claims must be recorded with the Bureau of Land Management by Sept. 28, 1977, or be declared null and void. This provision enabled many parks to summarily dismiss thousands of outdated claims throughout the West. In Capitol Reef National Park, a total of 189 unpatented claims were recorded by the September 1977 deadline. The National Park Service challenged each of these claims, usually on the inability to prove a valid discovery prior to the 1969 withdrawal of the land. By 1982, all but the Rainy Day Mines #2 and #3 and been declared invalid. [113] When the Rainy Day claims were finally nullified in 1986, the threat of resource damage from hard rock mining within Capitol Reef was over. [114]

There were, however, three oil and gas leases remaining on state-owned sections within park boundaries in 1986, down from 13 in 1970. [115] Since the State of Utah had assured Capitol Reef managers that these leases would not be renewed, and because the possibility of their becoming active was extremely remote, oil and gas leases within the park were effectively curtailed as well. [116] Thus, by the end of the 1980s, mining and mineral exploration within Capitol Reef National Park had been either suspended or eliminated.

Outside encroachments on Capitol Reef National Park, however, are another matter. Since the park was created in 1971, several large energy-extraction ventures in and near the park have been proposed. The first of these were proposals to build power plans southwest and northeast of the park; later came proposed coal, tar sands strip-mine operations, and imaginative plans for tapping oil and gas in the southern end of the park.

Oil And Gas Exploration

There has been periodic drilling of oil and gas in various areas surrounding Capitol Reef National Park since the 1920s. By the time the national park was created in 1971, there were approximately 6,000 acres of leases within the park, mostly on state-owned sections. There were also hundreds of other leases immediately adjoining two-thirds of the park boundary. [117]

By 1974, all but five oil and gas leases within Capitol Reef had either expired or were withdrawn. While the specific reasons for the lease withdrawals are not known, it seems likely that the hindering presence of national park regulations, coupled with high recovery costs, outweighed the possibility that valuable deposits could be found beneath park lands. [118]

The remaining five leases, scheduled for termination by mid-1980, were all located in the southern end of the park. One was just north of the Burr Trail, three were in the vicinity of the Rainy Day Mines, and all of section 18, Township 36 south, Range 9 east was claimed by Viking Exploration, a subsidiary of Sun Oil. This latter lease, along with similarly owned leases in adjoining sections in Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, proved the most troubling of all the oil and gas leases in the immediate area. [119]

Trans Delta/Viking Exploration Lease: 1972-1982

In August 1972, Trans Delta Oil and Gas Company, the designated operator for Viking lease U-9406, notified the regional Bureau of Land Management office in Kanab of its plans to begin initial exploration on leases soon to be incorporated into the new Glen Canyon National Recreation Area. These were less than a half-mile south of Capitol Reef National Park. To gain access, Trans Delta would improve the existing road and build additional road into this rugged, scenic area along the eastern escarpment of the Circle Cliffs. [120]

Trans Delta faced dealing with numerous federal agencies with conflicting missions, mandates, and agendas. The United States Geological Survey, which was responsible for the lease, actively encouraged exploration of the potentially major oil field under the Circle Cliff/Waterpocket Fold contact. The fledgling Glen Canyon National Recreation Area was struggling to comply with congressional requests for wilderness studies, while also permitting mineral exploration. The Bureau of Land Management was placed in the unenviable position of coordinating all the paperwork and correspondence, as well as controlling most of the access route to the drill site. Capitol Reef National Park was involved only because Trans Delta had determined that it would be less expensive and less destructive to detour its access road around the head of a canyon, which meant building a small section within the park. [121]

Throughout 1973, the USGS, the BLM, and the National Park Service attempted to coordinate the necessary environmental assessment. The National Park Service objected that the environmental assessment was not thorough or detailed enough, and argued that an environmental impact statement was needed. The U.S. Geological Survey disagreed, unilaterally approving the Trans Delta drilling application. [122]

At this point, the National Park Service had a choice. It could refuse to issue any special-use permits for the road building and drilling, thereby alienating the USGS just as its support was needed in the upcoming wilderness designations for Glen Canyon National Recreation Area. Or, the National Park Service could reluctantly issue the permits, hoping that environmental organizations would seek an injunction against the operation on the grounds that an environmental impact statement was needed. This second alternative would also show the local communities that some mineral exploration would be approved within the new recreation area. This was the alternative chosen by Regional Director J. Leonard Voltz. For the sake of federal agency unity and positive local publicity, and gambling that the environmentalists' lawsuit would hold up the project, both Capitol Reef National Park and Glen Canyon National Recreation Area were instructed by Voltz to issue the appropriate special-use permits. [123] National Park Service Acting Utah Director James L. Isenogle stated:

We have absolutely no fear of losing the respect or cooperation of the conservationists in the State of Utah as a result of the Trans-Delta case. They perceive our purpose in the sequence of events leading to the litigation and fully understand that the Service can, and probably will win more wilderness in Glen Canyon by losing this case in court than we could hope to by arguing our differences with USGS at the Departmental level and our position with residents of southern Utah and the State Government. [124]

The Sierra Club did indeed seek an injunction against Trans Delta and the various federal agencies in early December 1973. As a result, all oil and gas leases in Glen Canyon were suspended until a comprehensive mineral management plan could be completed. The strategy chosen by the National Park Service had worked. [125]

Then, in 1982 Viking Exploration resumed its request to drill in the same area. [126] This time, an elaborate plan to pipe the oil across Capitol Reef National Park ensured that park managers would be closely involved.

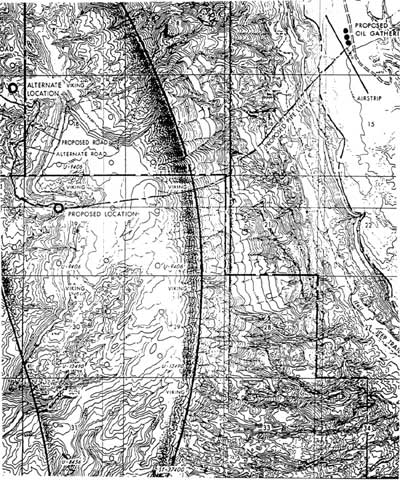

Viking planned to use the access route initially identified by Trans Delta back in 1973. If a valuable discovery were made, Viking would drill on other leases in the immediate area, including those within Capitol Reef. To get the oil from the isolated drill site, Viking proposed constructing a pipeline down the east face of the Waterpocket Fold, across Halls Creek near the Fountain Tank tinajas, and up to an oil storage and loading facility near the abandoned air strip on Thompson Mesa (Fig. 42). Most of this route would be through a state-owned section of land within the national park. [127]

|

| Figure 42. Viking pipeline proposal. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Over two days of meetings (Sept. 28-29, 1982) at Page, Ariz., Viking representatives laid out their proposals to the management staffs of Capitol Reef and Glen Canyon. Superintendent Hambly reported that, while the meetings were cordial, the proposal to construct a pipeline across the lower Waterpocket Fold was a cause of great concern. Viking had already contacted the Utah State Trust Lands Office, which had advised the company to construct the pipeline right away. This action would allow Viking to avoid any entanglements resulting from the likely transfer of state land to Utah's national parks, under consideration as part of the "Project Bold" proposal. This attitude on the part of the State of Utah, according to Hambly, gave Viking the impression that state school sections were "fair game for some sort of activity." [128]

Hambly also thought the Viking representatives were unfamiliar with the topography of the landscape on which they were planning to build. He wrote:

It was pointed out that aside from the undesirability of having pipelines through Halls Creek, Viking would have to contend with a 2,000 foot vertical drop at 50-60 degrees on the east side of the canyon with an additional 800-1000 foot vertical cliff on the east side of Halls Creek - all of this over rock where a pipeline could not be buried or the area reseeded to reclaim the land. Flight over the area on September 29, seemed to convince Viking of the unfeasibility of pipeline construction through Section 16 [the state section in question]. [129]

But Viking did not give up on the pipeline altogether. As an alternative to the climb up Thompson Mesa, the company tentatively proposed building the oil collection facility at the bottom of Halls Creek. Hambly objected to the proposed drilling within park boundaries. Viking responded that directional drilling from outside the park could be done, but it would be prohibitively expensive. [130]

In the end, Viking's elaborate plans never came to fruition. When the company was denied permits in 1981, it renewed efforts the following year. However, Viking was never able to prove it had a valid lease within the park, nor did it ever submit the required plan of operations. Consequently, all of Viking's permit applications were summarily denied. [131] The protections provided by the Mining in the Parks Act put a halt to Viking's plans early in the process.

As of 1994, all oil and gas leases are terminated within Capitol Reef National Park. Under current law and in the current political climate, it is safe to say that oil and gas drilling will not be a threat in the immediate future. Nevertheless, the potential for drilling has been identified and is well known. Future drilling ventures can be anticipated once there is a pivotal change in price of oil.

Coal-burning Power Plants

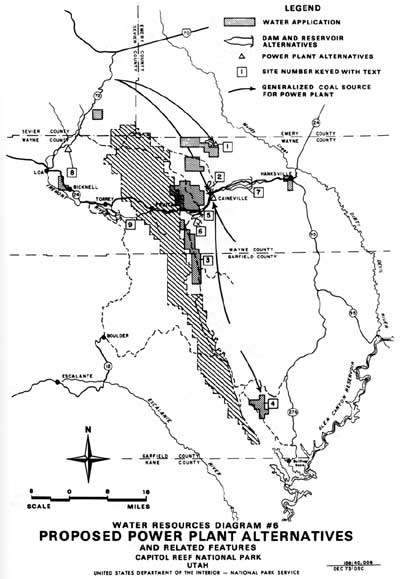

In the early 1970s, a proposal to build a large coal-burning power plant on top of the Kaiparowits Plateau, 30 miles southwest of Capitol Reef, received national attention. [132] Even while this classic battle between developers and environmentalists was shaping up, another enormous power plant was proposed for construction only 10 miles east of Capitol Reef. Located on Salt Wash at the base of Factory Butte, this $3.5 billion plant was projected to bring over 11,000 workers to the area, use 10 million tons of coal a year from neighboring Emery County, and consume 50,000 acre feet of water per year. This water would be provided by a dam and reservoir on the Fremont River, and by supplemental ground water wells. In return, the plant would produce a peak 3,000 megawatts of electricity for several Utah and southern California communities for 35 years (Fig. 43). [133]

|

| Figure 43. Proposed power plant alternatives. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

The Intermountain Power Project (IPP) was funded by a loose consortium of Utah, Nevada, and California communities. In the early 1970s, the IPP was considered only a pipe dream. Then, when the Kaiparowits Project was withdrawn after lengthy court battles made production too costly, IPP was resurrected in 1976. [134]

The close proximity of low-sulfur coal, the unclaimed water in the Fremont River, the assumed support of local communities desperate for economic growth, plus the relative isolation of the Salt Wash site combined to make the Caineville-area site appear ideal. The only stumbling block was the presence of a national park only 10 miles away.

Why IPP officials believed they would be permitted to build an enormous power plant so close to Capitol Reef National Park is unclear. In an apparent attempt to pre-empt objections, IPP emphasized in all its planning documents that its pollution control measures were the most stringent available, and pointed out that prevailing easterly winds would carry smokestack emissions away from the park. Officials predicted that for just a few days of the year would the wind shift and bring an estimated 10 tons of nitrous oxides, 1.6 tons of sulfur dioxide, and 0.4 tons of fly ash per hour into the Waterpocket Fold. [135]

IPP also maintained that considerable thought had gone into selecting the plant location. The facility would be built in a valley surrounded by high Mancos cliffs, so that only the tips of the smoke stacks would ever be visible to passersby. Further, the water necessary to cool the plant operation would consist of the unclaimed winter runoff in the Fremont River. IPP managers argued that their water storage system would actually stimulate agricultural development in the eastern end of Wayne County. Finally, the 11,000 construction workers and 500 full-time employees needed to operate the plant would be accommodated by building one or more complete towns in the area between Caineville and Hanksville. [136]

Although countering objections were raised by some local residents in a rare partnership with environmentalists, air quality regulations would prove to be the silver bullet that killed the proposal. Even while IPP was finalizing its plans, Congress, as part of renewing the Clean Air Act, was deciding whether all national park lands should be designated as Class I airsheds -- meaning that park air quality would be protected by the strictest standards. Even if Congress passed the 18-day variance supported by the Utah delegation, IPP would probably be unable to meet the new requirements. [137] As IPP Project Engineer Jim Anthony complained to the press, "The unrealistic standards of the proposed [Clean Air] legislation would prevent construction of the Intermountain Power Project because of its proximity to Capitol Reef." [138]

Unfortunately for IPP, Congress passed and President Jimmy Carter signed the revised, more restrictive Clean Air Act into law the next year. The August 1977 act states, "National parks which exceed six thousand acres in size and which are in existence on the date of enactment of the Clean Air Act Amendments of 1977 shall be class I areas and may not be redesignated." [139]

Even though Congress allowed each state to permit some variance to the strict Class I requirements, the president, through his secretary of interior, would have the final say. This virtually guaranteed that Capitol Reef National Park would be protected from any nearby coal-burning power plant, so long as environmental protection was a presidential priority. [140]

It soon became clear that the Carter Administration would not condone such a variance for Capitol Reef. Secretary of Interior Cecil B. Andrus quickly notified IPP managers that they had better start looking at other possible sites. [141] Project President Joseph C. Fackrell was understandably "disappointed." After all, $7 million dollars had been spent on background environmental research for the Salt Water location. Secretary Andrus recognized the burden this put on IPP, but maintained that the location so near Capitol Reef was simply unacceptable. Instead, Andrus urged IPP planners to focus their attention on a site near Lynndyl, Utah, just north of Delta and about 100 miles northwest of Capitol Reef. [142]

In 1979, IPP decided to stick with the Salt Wash site as its preferred location, but consented to prepare an environmental impact statement for the Lynndyl site, as well. Even as late as 1981, Garkane Power Association and a group calling itself Deseret continued to hope for a smaller coal-burning power plant in the Salt Wash area. [143] All these plans were rejected by the Department of the Interior, the Lynndyl site was finally chosen, and a half-sized, 1,500 megawatt plant began operations there in 1987. [144]

This plant joined other coal-burning power plants surrounding the national park lands of southern Utah and northern Arizona. As of 1994, conservation measures have actually decreased the demand for the electricity generated from these plants. In fact, once the Lynndyl plant was completed, its 1,500 megawatts of electricity were merely surplus -- not really needed at all. [145]

A convenient, timely change in the 1977 Clean Air Act prevented construction of a huge, coal-burning power plant 10 miles east of Capitol Reef National Park. Remarkably, few people have ever heard of the Intermountain Power Project -- once the most significant threat to Capitol Reef National Park.

Henry Mountain Coal Fields

There are two fairly large concentrations of coal located less than 10 miles from Capitol Reef National Park. The southern end of the Emery coal fields is approximately five miles north of the park boundary. Portions of this field further from the park are presently being mined to supply coal to the Emery (Hunter) power plant near Castle Dale, Utah, and other locations. [146]

The Henry Mountains coal field, located between the park's east boundary and the Henry Mountains, is estimated to contain more than 200 million tons of strip-minable coal. The majority of the extractable coal is located in the Emery Sandstone member of the Mancos Formation. In the early planning stages of the Intermountain Power Project, it was anticipated that this coal could supplement the Emery fields in providing a steady source of fuel for the proposed Factory Butte plant. [147] But according to the 1974 park wilderness proposal, the value of this reserve is "reduced by the relative thinness of the seams..." In addition, states the proposal, "some of the Henry Mountains coal is seriously split by non-coal interbeds and is high in ash." [148]

These disadvantages, plus high transportation costs, have discouraged extraction attempts. Yet, no matter how insignificant the results, each venture proved extremely troubling to Capitol Reef managers.

When Capitol Reef National Monument was expanded in 1969, nearly 1,760 coal prospecting permits were pending. Most of these permits were probably for the western edge of the Henry Mountain coal fields, in the area between Cedar Mesa and the Burr Trail, along the western edge of Swap Mesa. Many of these permits were no doubt excluded when the final park boundary was reduced and relocated along the western rim of Swap Mesa. [149]

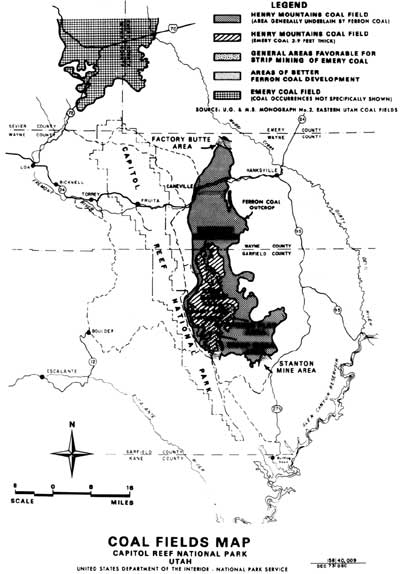

Beginning in 1974, the Utah State Land Board debated whether to withdraw two of its sections from the park so that coal mining could commence. The two sections were the entire state-owned section on the north side of Divide Canyon (T32S R8E S32) and portions of a state-owned section directly south of Divide Canyon on the edge of Swap Mesa (T33S R8E S17). Of the estimated 17 million tons of the Henry Mountain coal fields that were believed to lie within Capitol Reef, these two sections contained a significant percentage (Fig. 44). [150] According to Nephi, Utah mining contractor Robert Steele, who made the initial request to the Utah Land Board, the National Park Service had deliberately blocked access to a location that contained "two beautiful coal banks 15 feet wide." Steele argued that the Divide Canyon section alone held $240 million worth of coal. [151]

|

| Figure 44. Henry Mountain coal fields. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

In 1975, the Utah State Legislature passed a resolution initially sponsored by the Wayne County Board of Commissioners to alter the eastern boundary of Capitol Reef National Park. The alteration would allow access to and coal mining at Divide Canyon and Swap Mesa. The resolution was sent on to the Utah congressional delegation. [152] A year later, the state land board also asked Congress to exclude the two state-owned sections from the park. There is no record of any action taken at the congressional level. [153] In January 1977, the state land board again considered the issue. At that time, NPS Regional Director Lynn Thompson wrote a letter to the board pointing out that the area was on the eastern boundary of the Oyster Shell Reef. The reef, an ancient deposit of fossilized shells and sea life, would be destroyed by any coal mining in the area. [154] At this point, the attempt to carve out these coal-containing sections of Capitol Reef was dropped. This initial effort to mine coal on Swap Mesa most likely died due to a lack of congressional support and the National Park Service's determination to protect the park from coal mining encroachments by maintaining its existing boundaries. [155]

Then, in 1981 and 1982, there was a renewed bid to strip mine the Henry Mountain coal fields. Meadowlark Farms, Inc., a subsidiary of AMAX, submitted a proposal to the Bureau of Land Management to excavate areas on Wildcat, Swap, and Cave Flat Mesas. All these strip mines would be within sight and sound of much of the South District of Capitol Reef. [156] In February 1982, the BLM's Richfield District Office completed a draft unsuitability study on the Meadowlark prospects. [157] It concluded that most of the area was unsuitable for mining because it would threaten the Henry Mountain bison herd's habitat. The area that was determined eligible for coal mining included over 108,000 acres suitable for underground mining and 25,700 acres -- partly bordering Capitol Reef-- suitable for strip mining.

Yet, nowhere in the unsuitability study is Capitol Reef National Park even mentioned. Evidently, the BLM would allow coal strip mines on the park's boundary, within easy sight and sound of park roads and backcountry, without ever considering impacts on Capitol Reef's resources. This oversight brought a strong letter of protest from Regional Director Lorraine Mintzmyer. [158] Meadowlark's mining permits were a significant source of concern for park management through 1983, when AMAX finally relinquished all rights to its preference-right coal leases on the west slopes of the Henry Mountains. [159]

Tar Sands

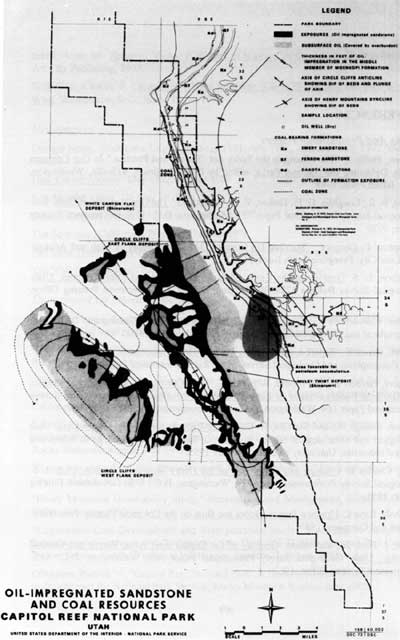

The final encroachment threat to be discussed concerns the large deposits of oil-bearing sandstones found among the Circle Cliffs, partly within park boundaries. From the 1960s to the 1980s, some speculators believed that the thick oil saturating the sedimentary layers could someday be commercially recoverable. In the 1974 draft wilderness study, geologists estimated that the deposit could yield as many as 700 billion gallons of oil, with a potential value of $2.2 billion (Fig. 45). [160]

|

| Figure 45. Circle Cliffs tar sands. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

In the 1969 debates over the monument's expansion, the potential of the Circle Cliffs tar sands was used to argue that the monument boundaries were too large, and would restrict or eliminate multiple uses of certain areas. William P. Hewitt, the director of the Utah Geological Survey, was one who argued during the 1969 congressional hearings that these reserves should not be locked up forever. Hewitt declared, "In today's market, none of these resources represents a commercial deposit; yet, the growing pressure on our known resources insures that any or all of them will become significant in the future." [161]

Hewitt and many others argued that if the monument (and later park) boundaries were to remain as proposed, there should at least be allowances for exploration and future mining to accommodate economic pressures or technological advances.

The most significant attempt to mine the Circle Cliff tar sands occurred in 1983-84. Under federal incentives to produce alternative energy sources, William C. Kirkwood, a Wyoming oil and gas firm, submitted a plan to the Bureau of Land Management to convert oil and gas leases to combined hydrocarbon leases covering 60,000 acres of BLM and Glen Canyon National Recreation Area. Of this, 22 miles would border Capitol Reef National Park. [162] Since the land was contiguous to a national park, the 1982 BLM/NPS Memorandum of Understanding on Combined Hydrocarbon Lease Conversions stipulated that the Bureau of Land Management must consult with the National Park Service before any plan of operation was approved. [163]

The BLM's 1984 draft environmental impact statement on the Circle Cliff tar sands operation determined that a 2,000-barrel per day operation was the preferred alternative. While significantly lower than the 32,000-barrel per day desired by Kirkwood, the smaller amount would barely keep the operation within Capitol Reef's Class I air quality standards. Any expansion of this would violate federal law. The environmental impact statement also determined that the Boulder-Bullfrog road could not be used to haul the oil from the site, since this would adversely impact the nature of the road, which was primarily used by tourists for sightseeing. The BLM suggested that a slurry pipeline through Dixie National Forest would be the best alternative for transporting the processed petroleum out of the area. [164]

Why this project was never initiated could not be determined from available documentation of the matter. More than likely, the fairly strict requirements of the environmental impact statement persuaded Kirkwood to abandon its attempt. A drop in oil prices and lack of success from other oil shale projects may also have discouraged the project. This is the last known effort any company has made to gain access to the Circle Cliff tar sands.

Conclusions

Numerous attempts to extract minerals, coal, and petroleum in and around the Waterpocket Fold country have proven largely unsuccessful. Prior to the 20th century, gold was the prospector's mineral of choice. While the presence of gold in the sandbars of Glen Canyon or in small pockets in the Henry Mountains brought many hopefuls to the region, no one made his fortune mining there. If these first prospectors made any lasting contribution at all, it was in carving out some of the first supply trails on the eastern edge of the Waterpocket Fold.

For the first few decades of the 20th century, mining activities were fairly quiet. Then, Cold War demands for uranium created the largest mining boom on the Colorado Plateau and within Capitol Reef National Monument. Speculation was encouraged by federal government supports and lax, outdated mining laws. The uranium boom threatened the integrity of both Capitol Reef's resources and management. Fortunately, little productive ore was found in the monument, and the Oyler Mine, believed to hold the greatest potential, was snarled in legal red tape throughout the entire boom. Yet, scars were made within the boundaries of the old monument and on lands later incorporated into Capitol Reef National Park. Persistent efforts to mine at Capitol Reef compelled the National Park Service to invest a lot of time and money in having all mining claims within the monument declared null and void.

The combined impact of the 1976 Mining in the Parks Act, the Federal Land Policy and Management Act, and the 1977 Clean Air Act has been to give parks added protection in fending off mining and drilling ventures. These laws have sometimes helped prevent recent attempts to build coal-burning power plants and gain access to oil, gas, coal, and tar sands within or near park lands -- for the time being. "Extraction of coal, oil, and gas near the park," cautions the 1989 Capitol Reef Statement for Management, "remains a possibility." The document continues, "Coal and tar sand deposits are considerable and only slight changes in the international pricing structure and/or internal availability could reawaken active interest in these south central Utah resources....Park personnel will track any reawakened interest in extraction of these mineral resources." [165]

The continued improvement of the region's transportation network could also encourage future mining operations in the previously inaccessible Waterpocket Fold country.

Today's park managers, armed with increasingly detailed resource data, are well prepared to track potential encroachments and evaluate potential resource impacts. Ultimately, however, the best insurance against future threats to the integrity of National Park Service lands and resources is continued enforcement of restrictive regulations and close cooperation with the Bureau of the Land Management, the U.S. Forest Service, and the State of Utah.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

http://www.nps.gov/care/adhi/adhi15b.htm

Last Updated: 10-Dec-2002