|

Capitol Reef

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER 8:

THE ESTABLISHMENT OF

CAPITOL REEF NATIONAL MONUMENT (continued)

Wayne Wonderland To Capitol Reef,

1933-1936

The campaign for Wayne Wonderland in the early 1930s seems to have taken a back seat to the struggle for Cedar Breaks, but this probably had to do with Roger Toll's busy schedule. Before Toll's next visit to Capitol Reef in November 1933, there was a considerable amount of maneuvering both in support and opposition to the proposed national park.

Ephraim Pectol was now the Wayne County representative to the Utah Legislature. Through his efforts, a memorial resolution was passed urging quick action on a Wayne Wonderland national park or monument. Signed by Gov. Henry Hooper Blood on March 15, 1933, the resolution to Congress is the first document detailing the area's proposed boundaries and the motives behind local support for Capitol Reef. [49]

The resolution, passed unanimously by the House, urged that the "scenic, archeological and geological value" of the area, "pronounced worthy" by "competent authorities," could be "brought to the attention of the American people only by having them set apart and designated as a national park or a national monument." This resolution marks the first time that a national monument was considered by promoters to be as acceptable as a national park. This may have been as result of the investigations of Allen and Toll the previous two years, or it may simply have shown the flexibility of supporters desiring any kind of federal designation for the area. The second part of the resolution combined the creation of a national park or monument with the hopes for "future highway construction" that would connect a "chain of natural wonders" from Mesa Verde and Natural Bridges to Bryce Canyon, Zion and Cedar Breaks. [50]

The connection of a Wayne Wonderland park with future highways has been evident since the first promotions a decade earlier. Local and state interest in this national park or monument clearly was overwhelmingly motivated by a desire for economic benefits that a tourist boom would bring to the area. This desire was particularly understandable, considering that these events occurred in the depths of the Great Depression. According to the Richfield Reaper:

The creation of a national monument in Wayne County is regarded as the first step toward completing an east-west highway across southern Utah...Such a route would provide an all-winter auto highway from Texas and other states in the southwest and south into southern California, and would also open up a new line of travel for the remainder of the year to tourists who seek opportunity to visit the newer wonderlands of Utah. [51]

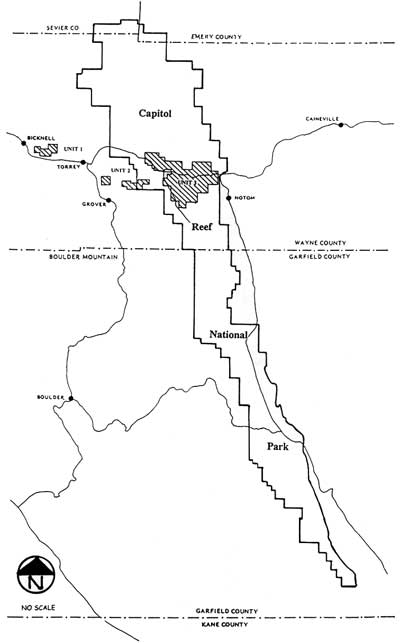

The boundaries as proposed in the 1933 resolution were most likely drawn by Rep. Pectol. Three separate units were proposed: Unit 1 would encompass Velvet Ridge, the colorful bands of Chinle exposed above the Mummy Cliffs between Bicknell and Torrey; Unit 2 would protect the archeological and scenic features within the Fremont River corridor west of Fruita; and the boundary of Unit 3, the heart of new park, took in the lands from Chimney Rock Mesa north of the approach highway, east through Longleaf Flat to the Navajo Sandstone Domes and perhaps as far as Hickman Bridge and Capitol Dome. The line was south of Spring Canyon. From Capitol Dome, the boundary went south, which would have protected only the western rim of the cliff line as far Grand Wash, and then it jogged southeast to include the slickrock domes around Fern's Nipple. Only the western entrance to Grand Wash was included. The western line of Unit 3 would have enclosed only about one mile of the road to Capitol Gorge (at the entrance to Grand Wash) and would have skirted around the private lands of Fruita. In general, the Unit 3 boundaries would have included just the northern and eastern cliff rim, including the Navajo Knobs and Cohab Canyon, plus the scenic heart of the Fremont River canyon as far as Capitol Dome. In its gerrymandering around the private lands of Fruita, the resolution appears to have omitted Hickman Bridge. This proposal also left out the Grand Wash narrows and Capitol Gorge (Fig. 17). [52]

|

| Figure 17. 1933 monument boundaries, as proposed by Utah State Legislature. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

No documentation has been found justifying the proposed boundaries or indicating influence by economic concerns. Except for small areas near the Fremont River corridor and the Longleaf Flats area just north of Fruita, all the proposed land was free of traditional grazing use. Apparently, Pectol had wanted to include the upper Pleasant Creek drainages west of the Waterpocket Fold, but this idea was dropped in response to objections by stockmen. [53] The reason for excluding Fruita was obvious.

Pectol wrote to Director Albright informing him of the resolution and the desire for action. Albright responded with cautious encouragement. The director noted that he had heard "very fine reports on the Wayne Wonderland," but added that further investigation would be necessary before the National Park Service could proceed any further. [54]

With the legislature's resolution as a tangible framework to follow, Roger Toll arrived in Torrey on October 31, 1933. In the company of Bishop Pectol, Toll spent four days in a car, on foot, and on horseback examining the three sections proposed in the resolution. Pectol took Toll to the top of Boulder Mountain, to Velvet Ridge, and to an overlook of the upper Fremont River canyon. They concentrated most of their attention on the "Chimney Rock" unit. After viewing Hickman Bridge and Cassidy Arch, Spring and Chimney Rock Canyons, Grand Wash, Capitol Gorge, and specific archeological sites, Toll proclaimed the area to be "the best of the three units." This was because, he reported later, the Chimney Rock unit included "narrow gorges, sandstone cliffs, two natural bridges, archeological remains, pictographs, petrified trees," and other interesting features. "It is," he added, "rich in color." [55]

After Toll left Fruita for the last time, it would take him six months to complete his report and send it on to Arno Cammerer, the new National Park Service director. The final report recommended that the Chimney Rock and Palisade Canyon (Fremont River gorge) areas (Units 2 and 3 of the state resolution) be accurately surveyed and then established as Wayne Wonderland National Monument. [56]

The Unit 1 or Velvet Ridge section was dropped from consideration because it was mostly Forest Service land and its scenic value was far less than that of the other two units. Interestingly, this Velvet Ridge unit was the watershed for Torrey. Toll implies that the motivation for reserving this land in a national monument was to prevent grazing near the streams and open ditches carrying Torrey's water down the mountain. Of course, the ongoing disputes with the Forest Service also must have had an impact on Toll's decision to omit this small, disconnected section from the proposed monument boundaries. [57]

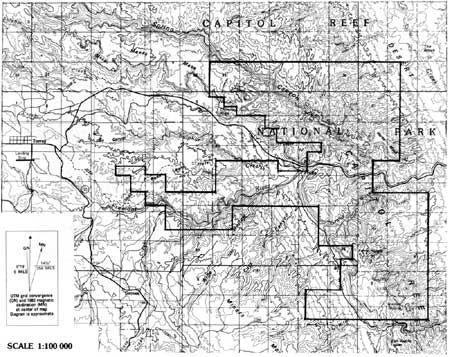

Toll's report refined the boundaries as first submitted in the concurrent resolution, expanding some of the areas and correcting some minor discrepancies. Toll recommended the boundaries be enlarged to include Horse Mesa, lower Spring Canyon to its mouth, all of Grand Wash, and the Capitol Reef section of the Waterpocket Fold down to the domes and canyons just north of Capitol Gorge. He further recommended that the Fremont River section and the Capitol Reef sections be joined just south of Fruita, bringing almost the entire Fremont River corridor into the proposed monument. As for the private lands of Fruita, they were bypassed once again (Fig. 18). [58]

|

| Figure 18. 1934 monument boundaries, as proposed by Roger Toll. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

As Toll was finalizing his report and recommendations, the ACCSU, elected officials, and the livestock lobby were also increasing their activities. In January, the civic clubs drafted their own resolution endorsing a Wayne Wonderland National Park. Other than specifically mentioning support for a national park, the ACCSU resolution is remarkably similar to that passed by the state legislature a year earlier. The ACCSU resolution was sent to the National Park Service, Gov. Henry Blood, Senators Elbert Thomas and William King, and Reps. Jim Robinson and Abe Murdock. The correspondence among these parties indicates their continued support for the project. Sen. King took it a step further, requesting a progress report from the National Park Service. Associate Director Demaray replied that, due to Toll's busy schedule, the final field report was not yet completed and that no action could be taken until then. [59]

Two weeks after requesting this update, King wrote to Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes. This letter, however was not an endorsement, but rather a cover letter to petitions signed by Wayne County residents against the proposed park. Ickes responded that the petitions would be taken into account once the field reports were completed. [60]

The petitions, with 91 signatories opposed to the creation of a national park in Wayne County, are the only surviving documentation of resistance. Prior to this substantial expression of opposition, grazing issues, such as the incompatibility between livestock needs with National Park Service policy, had been considered with every resolution and boundary proposal. According to the petition, however, the local ranchers felt that their concerns had been ignored. This is evident in the letter to Sen. King:

Through newspaper articles of recent date, it is apparent that certain organizations and individuals are sponsoring a move to create a National Park here in Wayne County, State of Utah. It is apparent that these people are in most cases not residents of Wayne County and not interested in the well-fair [sic] of the local residents. The question of a National Park has never been presented for consideration of the public and does not represent the desires and wishes of the voting population. Since the livestock industry is the principle occupation of a majority of the residents and is the source of their means of living, we feel that it would be unjust and a detriment to permit the passage of any bill that would authorize the creation of a National Park thereby causing the curtailment or withdrawal of our grazing privileges. [61]

This petition crystallized resistance from stockmen. Had the ranchers been approached by agency officials about the early boundary proposals, this opposition from a powerful interest group may have been avoided. Instead, Rep. Pectol, the ACCSU, and other park supporters seem to have been the only ones consulted.

For example, in a letter to Rep. Pectol written on the same day that Toll filed his final report, Toll asked if this resistance from grazing interests reflected the "general sentiment of the County and of the State" and wondered exactly how his proposed boundary revisions would affect livestock. Pectol happily replied that opposition from grazing interests had been eliminated:

Our stock growers met with our Commercial Club, and the misunderstandings were quite well ironed out and eliminated, to the extent that many expressed regret that they were misinformed as to the extent and intent of the park, and many have signed a reversal which will be sent direct to Director Arno B. Cammerer. [62]

The minutes of that meeting are not available, but presumably the ranchers agreed to withdraw their opposition to the monument once they were assured that it would be small and include little or no grazing land. In a statement from Alenander A. Clarke, president of the North Slope Grazer's Association, it is clear that the stock growers' objections were tied to the rumored extent of the monument's size:

[T]he opposition and antagonism once existing against said park has greatly subsided....I will state further that most all were misinformed as to the extent and location of the park and the present outlines, as has been designated to Roger W. Toll, seems to meet with no objection as no grazing interests are at stake. [63]

From this point on, there is no documented resistance to the proposed national monument, yet the impact remained indefinitely. The petition and its withdrawal were all based on concerns over the monument's size and its impact on grazing. The lasting effect of the petition was not only to delay National Park Service action on the proposed area, but more significantly, to help sway agency officials toward the less threatening national monument status.

As to the issue of boundary adjustments, Pectol agreed with most of Toll's proposed additions to the north, east and south. The Utah State Legislature's Committee on Parks and Roads, on which Pectol served, endorsed Toll's recommendation, with a small southern addition to take in both sides of Capitol Gorge. The committee also voted to exclude Units 1 and 2, thus eliminating the Velvet Ridge and the Fremont River corridor east of Fruita. [64]

Toll endorsed the addition of Capitol Gorge and elimination of the Fremont River gorge, sending the recommendations on to Washington, D.C. He informed Pectol that an accurate boundary survey was the next step, before anything else could be done. Toll also specifically recommended that national monument status should be pursued, since the congressional action needed to establish a national park was doubtful, given the pressing needs of the Great Depression. Although not mentioned in this letter, the grazing conflict must have been an important factor in this decision, as well. Sensing his disappointment, Toll assured Pectol that "there have been several instances where national monuments have been changed to national parks when their value has been fully demonstrated." [65]

Meanwhile, the Utah State Planning Board was conducting its own independent investigation of the potential of Wayne Wonderland. Paul Arentz, supervising engineer for the board, visited the area during the early summer of 1934 and was impressed by the scenic variety of Capitol Reef. It is unlikely that he talked with either Pectol or any National Park Service officials, as he states that the area suggested by the "the citizens" is "an area of 6 miles by 20 miles." Even this area, over four times larger than the area under official consideration, was not enough for Arentz. He proposed that Wayne Wonderland be extended to include all the area from

Thousand Lake Mountain to the desert 30 miles thence south, bounded on the north by Boulder Mountain and on the east by the desert to an area southeast of Boulder Mountain called the Circle Cliffs near the old town of Boulder, Utah. This area recommended for Wayne Wonderland comprise[d] approximately 570 square miles. [66]

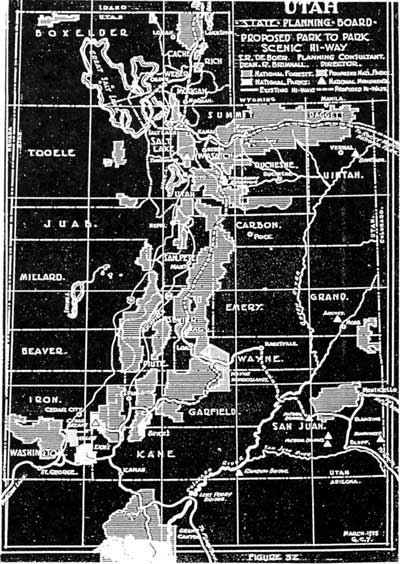

In the final report to the state board, consultant S. R. DeBoer recommended that "not less than 360 square miles should be acquired." Obviously, some members of state government were urging an enormous Wayne Wonderland national park or monument, even while the local grazing interests were trying to limit the area that the National Park Service would consider. DeBoer, Arentz, and others, however, were motivated by the limitless potential they saw for Utah as a recreational playground for tourists from around the country. To help sell Utah, they proposed a number of impressive projects. For example, they proposed building a series of scenic highways from the Grand Canyon to Salt Lake, and thence north to Yellowstone or east to the Rocky Mountains. From these main arteries, a secondary highway would be built from Zion and Bryce Canyon through Wayne Wonderland to Natural Bridges and beyond. This was an extension of Stephen Mather's park-to-park highway proposals back in the 1920s.

An additional, more ambitious scheme called for dredging the Green River through Stillwater Canyon to the junction of the Colorado to enable tour boats to navigate the rivers to a planned hotel at the confluence. This project was soon dropped from official consideration, but the link between a large Wayne Wonderland and the scenic highway that would bring tourism and business to southern Utah was endorsed in every year's recreational plans throughout the 1930s. [67]

When Arentz was in Wayne County, he noticed that Emergency Conservation Work crews were busy improving the road over Boulder Mountain from Boulder to Grover. He wondered if such crews could be put to use improving Wayne Wonderland as well. Herbert Maier, National Park Service/State Parks coordinator for the ECW, responded that the application was interesting, but that it arrived too late for consideration for at least another year. [68]

At the beginning of 1935, National Park Service Director Arno Cammerer officially petitioned Secretary Ickes, asking that lands being considered for monument inclusion be withdrawn from Taylor Act grazing districts. Included in this request were Wayne Wonderland, the Kolob Canyons adjacent to Zion National Park, a Yampa Canyon National Monument near Dinosaur National Monument, and an enormous area "in southeastern Utah and northern Arizona, on both sides of the Colorado River, from its junction with the Green River to Grand Canyon National Park." This huge area would be proposed a year later as Escalante National Monument. As for Wayne Wonderland, Cammerer described "spectacular scenery of red and white sandstone formation, narrow gorges, several natural bridges, some cliff dwellings of prehistoric Indian tribes, petrified trees, and other features of interest." Its attractions were at that time viewed by few people other than local residents, he observed, noting, "If a project for a highway across the Colorado River ...should materialize...[the area's] accessibility would be greatly increased." [69]

From this description, it is clear that the National Park Service was also hoping for the construction of that southern Utah highway to link its national parks from Mesa Verde to Zion.

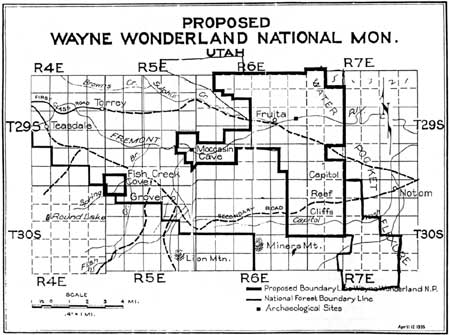

In 1935, Conrad Wirth, National Park Service assistant director for land planning, suggested expanding the boundaries to include the Moccasin Cave and Fish Creek Cove archeological sites west of the proposed monument. Because of a report from the Peabody Museum at Harvard (which sponsored the first archeological surveys by Noel Morss of the area back in the late 1920s), Wirth asked Pectol to consider reattaching the Fremont River gorge and extending this strip all the way to include Fish Creek Cove, near Teasdale. Wirth makes it clear that grazing considerations, rights-of-way, and the "successful cultivations" at Fruita would need to be considered before such an addition would be made. [70]

This proposed addition of the Fremont River gorge and Fish Creek would receive a great deal of attention throughout the year. The desire to incorporate Fruita as a smooth connection between the Capitol Reef sections and the narrow strip toward Fish Creek Cove would become the most significant legacy of this latest boundary debate. In April 1935, Pectol was officially informed by Associate Director Demaray that the town of Fruita was being considered as part of the monument in order to "provide for better administrative control along the course of the Fremont River." Assurances were made that "this arrangement would not place any hardship on the owners of private land as the proclamation for establishment would be drawn up to protect existing rights." [71]

In early 1935, the revised state plan for recreation was still promoting a 360-square-mile park. The scale makes specific boundaries difficult to determine, yet it appears that the state plan called for including the entire Spring Canyon and Polk Creek drainages up to the national forest boundary in the north, and the Waterpocket Fold as far south as the Circle Cliffs. The south and west boundaries would also abut the national forest line on the flanks of Boulder Mountain (Fig. 19). Nothing more specific is detailed in this 1935 state plan. It seems likely, however, that this proposal from various Utah officials was independently made, and was not being submitted with either the help or knowledge of the National Park Service, Pectol, or the Associated Civic Clubs of Southern Utah. [72]

|

| Figure 19. 1935 boundaries, as proposed by the Utah State Planning Board. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Meanwhile, the ACCSU was concerned that the National Park Service proposal for monument as opposed to park status would adversely affect development in Wayne Wonderland. Director Cammerer reiterated that the scientific and archeological features in the area lent themselves more toward monument status. Cammerer tried to calm the boosters' fears by reminding them, "Wayne Wonderland is no less important than other areas which have been classified as national parks." [73] Zion Superintendent Preston Patraw also tried to assure the ACCSU and Rep. Pectol that monument status was the best at the time. While acknowledging that monuments tend to receive less money and staff than national parks, he pointed out that funding is usually allocated on the basis of need. In other words, if Wayne Wonderland were made a national monument, its future allotment of funds would be governed more by its needs for protection and for service to visitors than by the fact that it was a monument rather than a park. Patraw pointed out that a Wayne Wonderland National Monument could be created through presidential proclamation much more quickly than a park could be established through the slow, congressional process. This would "hasten the time" when the area could receive improvements, as from the CCC. [74]

The CCC possibility must have been attractive to local businessmen because of the positive economic impacts it promised depressed rural Utah. Another argument for monument status came from Rep. Abe Murdock, who told the ACCSU that continued reports of opposition to Wayne Wonderland from area ranchers were "holding up the park status." Accordingly, the ACCSU decided to accept the national monument designation for the time being, but to continue pushing for a future upgrade to national park status. [75]

Superintendent Patraw visited Wayne County for the first time in March 1935 and was impressed not only by the scenery, but also by the recently graded dirt road into Fruita. Patraw reported to the director that the improved road would soon bring more tourists to the area. He urged that a couple of CCC camps be established within the year to begin work on "campgrounds, water and sanitation systems, trails, and so forth." [76] This visit by Patraw once again buoyed local hope for an imminent proclamation from the federal government. The Richfield Reaper reported that Patraw's visit meant that, at long last, the National Park Service finally intended to take action.

"When President Roosevelt issues the proclamation making the region a national monument," the Reaper predicted, "one of the most persistent fights ever started in southern Utah will end." According to the paper, all that was needed was a final boundary survey to pacify the grazing interest, and then the president could act. Few people, including Superintendent Patraw, realized that it would be another two years before the monument was established. [77]

In June, Patraw returned to Wayne County to conduct that final survey. Traveling by car, horseback, on foot, and by airplane, Patraw and his accompanying survey engineer, architect, and wildlife technician accomplished a great deal. They determined a new set of boundaries and the exact amount of public and alienated lands, evaluated the potential of the Fish Creek Cove addition, and conducted the first scientific examination of flora and fauna. The airplane trip (the first documented aerial inspection of the park) was significant because Patraw and his party determined that the Navajo Domes above Cottonwood and Burro Washes should be included, as should the entire eastern slope of the Waterpocket Fold (Fig. 20). This latest revision now put the southern boundary along the Wayne-Garfield county line and added several square miles to the east. Patraw talked with the Durfey family of Notom Ranch and Rudolph Cook of Floral Ranch, both along Pleasant Creek; neither objected to this expansion. The main argument for including the eastern sections was to encompass "the toe of the east slope of the Fold, for geologic reasons and to provide additional winter range considered by the Wildlife Division representative to be needed." [78]

|

| Figure 20. 1935 boundaries as proposed by Preston Patraw. The additions are imprecise, owing to aerial reconnaissance. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Patraw dismissed the potential of grazing in the proposed monument, suggesting that any extant grazing rights could be eliminated without too much of a problem. Yet, Zion National Park's superintendent was quite aware of potential conflicts with area stock growers. Apparently, Pectol tried to reassure Patraw that the ranchers would not object to these extensions because they incorporated no good grazing land. Patraw, however, was unconvinced. He reported, "[T]his assurance may not be taken as entirely accurate, but sufficiently so to indicate that whatever opposition might develop would probably be based more on the enlargement itself than on any grazing value included in the enlarged area." [79]

It seems Patraw realized that opposition was not tied directly to established grazing rights, but was generally concerned with any attempt by the federal government to restrict use of the open range. Bear in mind that at the same time Wayne Wonderland's boundaries were being drawn, the new grazing districts authorized by the Taylor Grazing Act were also being mapped out. Area ranchers sensed that their traditional, open use of the desert lands of Wayne and Garfield Counties was over. They must have been even more concerned over a national monument that seemed to be expanding, even if very slightly, with each National Park Service visit.

The private lands in Fruita were another concern for Patraw. He agreed with the National Park Service director's suggestion that Pectol work out new boundaries that would include Fruita. Yet, in Patraw's opinion, the National Park Service should actively attempt to purchase all the private lands. He argued:

Fruita is the logical place for locating the center of future monument developments, and under continued private ownership uncontrolled and competitive development of tourist accommodations is bound to follow progressively with [the] increase of tourist visitation. Owners will want to put up tourist camps, serve meals, sell souvenirs, and run dude ranches, or lease out parcels of their lands to others for the purpose. [80]

Patraw warned that the price, rather than the availability, of the land would be the main obstacle to purchasing the private holdings. There were an estimated 100 acres in fruit and alfalfa cultivation. One owner hinted that $1,000 an acre would buy him out, whereas the largest landowner, Cass Mulford, wanted $5,000 per acre. Obviously, at least some of the residents of Fruita were willing to sell their orchard farms, so long as their asking price was met.

The report concluded that administration and protection of the proposed monument would not present many problems--except for the private lands at Fruita. Trails from the canyon bottoms to scenic features such as Hickman Bridge could be easily built, and the only road through the monument was bound to get better. As a matter of fact, plans were already being made to divert Utah Highway 24 from Capitol Gorge to the Fremont River corridor. As for the Fish Creek Cove area, Patraw reported that the archeological ruins had already been extensively dug up, and that recent inscriptions had spoiled the rock art. Because of this vandalism, plus the fact that much of the area was privately owned, he advised eliminating this area and the Fremont River gorge (again) from consideration, unless a competent archeologist disagreed. [81]

Perhaps the most significant suggestion in Patraw's report was the change in name from Wayne Wonderland to Capitol Reef. According to Patraw, neither "Wayne" nor "Wonderland" were "sufficiently distinctive" to describe the proposed area. Since "Waterpocket Fold National Monument" was too long, Patraw suggested "Capitol Reef," the local name for the prominent domes and cliffs that would be at the center of the new monument. [82]

Some local residents and historians have assumed that the new name, "Capitol Reef," was thrust on the monument without the consent of the Wayne County boosters. [83] First, the name "Capitol Reef" was actually not very new at all. It was being used interchangeably with "Wayne Wonderland" in The Richfield Reaper as early as the 1925 promotions for a state park. [84] Second, the assumption that the name Capitol Reef was selected without local approval is also untrue. Roger Toll wrote Pectol after receiving Patraw's report, and asked his opinion. Toll liked the name change because "it is undesirable to apply the name of a county to the area since that suggests a much more local type of interest." [85] Contrary to some accounts, super-booster Ephraim Pectol seems to have agreed readily to the name change. A week later, Pectol wrote Toll:

Capitol Reef National Monument has been my selection for a long time as it embraces the Capitol Reef area, but [I] was fearful the service might think this would detract somewhat since 'Wayne Wonderland' had been placed on many of the maps.... 'Capitol Reef National Monument' suits me. [86]

A year later, Pectol did confide with Associate Director Demaray that he would have preferred Wayne Wonderland, but said that he was more than willing to stick with the name Capitol Reef. [87]

Now that the name and monument status were agreed upon, all that remained was to set final boundaries that would meet the approval of all interested parties. Pectol made one last attempt at larger boundaries when he proposed that the entire area between Fruita and the national forest lines be added, including the town of Torrey. Pectol was counseled by both Toll and Patraw that this was not a good idea, due to likely conflicts with private landowners, the forest service, and area ranchers. Finally, at the end of August, Pectol reluctantly withdrew this proposal. Pectol concluded that, since additional delays were undesirable, "the area now embraced [should] be accepted as outlined." [88]

Unfortunately, the definition of final boundaries was not easy. Consideration of private holdings, real and/or potential grazing rights, and the newly proposed, enormous Escalante National Monument would delay Capitol Reef's establishment for another two years.

The Escalante National Monument

Debate

A key reason for Capitol Reef's delay was the displute over the proposed Escalante National Monument. As mentioned earlier, resistance over Cedar Breaks National Monument and to Zion's expansion into the Kolob Canyon area came largely from multiple-use advocates such as miners and ranchers. Faced with a deepening economic depression and the passage of the Taylor Grazing Act, stock growers were particularly wary of additional federal attempts to regulate their livelihood. The announced proposal to exclude almost the entire Colorado Plateau from grazing in order to establish a huge national monument was met with the most determined and vocal resistance to date. The initial plan was to eliminate grazing from almost 7,000 square miles from Green River, Utah, south to the Arizona border, and from Moab and Blanding west to the town of Escalante, pending investigation of the area's merits as a national monument.

The Escalante National Monument proposal delayed Capitol Reef's final reports and boundary surveys, needed before presidential proclamation could establish Capitol Reef National Monument. Shortly after Patraw's report was sent to Toll, Assistant Director for Operations Hillory Tolson suggested that the Wayne Wonderland nomination be postponed until the National Park Service could determine how much land needed to be withdrawn from the newly created grazing districts. Tolson observed that this delay was particularly irritating to Rep. Murdock, who evidently was the only member of the Utah delegation pursuing the project. [89]

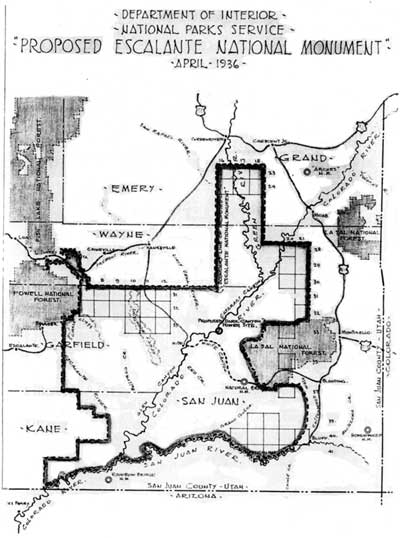

In December, Toll found out just how much land was being considered. The initial desire to create a national monument outlining some of the Colorado River's larger canyons in Utah now included not only the Circle Cliffs, but the proposed Capitol Reef area as well: Capitol Reef was to be swallowed up by Escalante, as it was "more logical to combine in one administrative unit" (Fig. 21). Another option briefly considered was to reduce the size of Escalante, and stretch Capitol Reef's boundaries down the length of the Waterpocket Fold, an option eventually taken some 60 years later. [90]

|

| Figure 21. 1936 proposed Escalante National Monument boundaries. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

In June 1936, National Park Service officials Patraw, Jesse Nusbaum and David Madsen met at Price with affected residents of the proposed Escalante National Monument. Although some (such as from Frank Martines, president of the Associated Civic Clubs of Southern Utah) supported the monument, most were ranchers and miners who made their living on the Colorado Plateau. Rancher after rancher spoke against the proposal. Even the state planning board representative insisted that the proposed area would have to remain open to mining and livestock use. [91] The result of this meeting was an immediate retreat by the National Park Service: the proposed Escalante National Monument was withdrawn for the time being. Further study of the Escalante area was proposed, "to determine where reductions may be made with least detriment to the project and, also, to establish the Capitol Reef area as a national monument without further delay."

The embattled Escalante monument was eventually reduced to a still-imposing strip varying between three and 50 miles in width between the confluence of the Green and Colorado rivers and the Arizona border. In an attempt to secure this land for the National Park Service, compromises would allow grazing and even permit construction of hydroelectric dams at the mouths of Glen and Dark Canyons. This proposed monument eventually evolved into Glen Canyon National Recreation Area and Canyonlands National Park. [92] Meanwhile, the focus shifted once again to creating a small Capitol Reef National Monument in isolated Wayne County.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

http://www.nps.gov/care/adhi/adhi8a.htm

Last Updated: 10-Dec-2002