|

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR

Conservation in the Department of the Interior |

|

CHAPTER X

CONSERVATION OF THE CHILD

OF ALL national assets in the conservation of which the department is concerned the children of the country are by far the most important. We husband our other resources only because there are children who will need them. But we can not take it for granted that our children will live or that they will be fitted to make the most of life's nonmaterial as well as its material resources.

It is with the child's years of rapid development, covering a fifth more or less of his life span, that the Office of Education of the Department of the Interior is concerned. The office is intimately interested in the welfare of the 30,000,000 children in attendance in our public schools and in the thousands who are privileged to be under formal instruction before or after their public-school days, but it conducts no classes and supervises no teachers. Its business is that of securing and distributing such information as will be helpful to educators in their work with children. The office is in a situation to scan the whole educational field in this country and abroad, to learn what is going on, and to point out what seem to be the high spots in its ever-changing procedures.

Life is subject to change, and modern life more than ever. Education is never at a standstill, whether considered transversely or longitudinally. Education is for life, and its processes must be continually adjusted to life as it is. Life grows more and more complex, and with this change education also becomes less simple.

There is need of such a central agency which will observe what is going on locally everywhere to fulfill in his school days the present and future needs of the child. There is abundant need for such information as it can offer.

|

| A Few of Uncle Sam's 30,000,000 Children of School Age |

Time was when only the child's mind, or at most his brain, went to school. True, his legs carried him to a little building of red, or other hue, and he made use of eyes, ears, and hands in the processes that went on therein, but the condition of these tools was of little concern to the schoolmaster, and there was less interest in other physical features of the pupil. Doubtless these matters would have meant more to the master if he (or anyone else) had had any usable information on the subject. Of course, there are those who would say that the child's physical condition is wholly a matter for the home. But what if the home has not been educated, or does nothing in such matters? The school is concerned in the conservation of all the resources of the child. His physical assets come first (if there is any first) and can not be separated from his mental belongings. Both must be at their best if we would make the most of him.

|

| The Illustrated Lecture |

The process of formal schooling in the twentieth century is an expensive one (costing something like $100 per year per child) and there is waste—waste of time, waste of effort, and waste of money in trying to educate children who are not in condition to profit by their schooling. For children absent on account of sickness, the mill runs without grist, and for the child whose life comes prematurely to an end the school machinery has run well-nigh in vain.

The Office of Education has concerned itself lately with the fundamental, though unpleasant, subjects of sickness and death in children of school age. Everyone is vaguely aware that there is needless illness and preventable death, but it takes the jar of big figures to stir us out of the mental habitude with which we are apt to look upon the events of current life. The death or illness of some child is a calamity in the child's home, but it hardly ripples the surface of community consciousness. The fact, furnished by the Office of Education, that a child of school age dies every 10 minutes hits hard, and even those who think only in dollars and cents blink at an estimated annual monetary loss from deaths at school age of about $1,000,000,000. Panics in the stock market and war debts seem insignificant beside such annual waste.

|

| The School Now Considers Matters of Health |

It is too much to expect that, because we are jogged out of lethargy by this information, we can at once do away with the unhappy condition. It is suggested, however, that the premature loss of life could be cut by 25 per cent. Comparisons are odious, but even with this reduction the deaths at school age would not be so proportionately low as they are in a half dozen countries abroad.

We are told that there is an average loss of some seven or eight days of school per child each year on account of illness—a total loss of 1,000,000 school years if one child lost it all. If a school is really worth attending, its efforts are wasted proportionately. If the child falls behind and can not catch up, there is added loss of time and school expenditure.

Again, we can not as yet prevent all this loss, but it could undoubtedly be discounted 25 per cent.

Hit hard by such large figures for sickness, schools are doing much, though they can not do all, to bring about conservation of life and of school days. Where the local schoolmen are not prepared to go about such saving, the department furnishes such information as is available for making school life and all life safer and more sanitary.

But because the child's life is conserved and his days in school are brought to a maximum does not necessarily mean that he is "all there" and making full use of his opportunities even when he is present. He may have been ill fed or have slept badly, and the sleepy and hungry child can not do good work. He may have eyes that see not all that is before them or ears that hear not all that is said to them. Under such circumstances there must be waste of time and effort on the part of the child and the school. School officials are fully informed as to the possibilities of waste from such causes and as to how the teacher, if no one else, may determine when a child is physically in shape for profiting by his schooling.

|

| The Child Needs Plenty of Sleep |

But this has only to do with the average child and from the physical standpoint—of saving him from premature destruction, from absence from school, and from mere unavoidable woolgathering when present. This is only the beginning of education and the conservation of the child. In order to make the most of himself the child needs to learn the value of his own bodily machinery and how to do his share in keeping it at its best. The program of the school itself should be so planned as to conserve his physical powers. "Play is the life of the child," and nowadays there must not only be play periods in the school day but the child must even be taught what and how to play. Life after school is not all work nowadays, and his education in play, physical and mental, becomes education for the conservation of leisure time through all his days.

|

| No Two Children Are Alike |

Not only is more leisure a feature of modern life but there is change in every direction. Education of the child in its mental aspects must keep pace with this change. The education of the past generation is not fitted for the present. While the fundamentals, the three R's, remain, methods of training in these R's change, while preparation for the more practical affairs of life becomes as varied and complex as modern life itself.

One of the fundamental conclusions of the committee on growth and development of the White House Conference was to the effect that "No two children are alike." To most of us this fact is so well known as hardly to deserve mention, and yet it is one which is too often ignored. The Office of Education would reiterate and reemphasize it. No two children are alike; and if we would make the most of each, we must find out how they differ and what can be done to meet the needs of each.

This is not so difficult with the majority, who differ in lesser degree. It is with those who vary further from the average, the "exceptional" children that the educator needs all the information available. Time was when such children simply dropped out of school. This made it easy enough for the school people and, under the circumstances, it was about as well with the child. But if you compel a child to attend school during a certain period of years and if you would make the most of his powers, you should meet his special needs at least halfway. Otherwise his schooling is a waste both for educator and child.

|

The physical side of the child looms up again when we think of children as different. The blind and the deaf are usually taken care of, but what shall be done with the child who can see but who by no means can be made to see as other children see? What about the child who is not deaf but yet can not hear intelligently the ordinary language of teacher or pupil or anyone else? What about the child who lisps or stutters, whose school life is more or less of a hell on earth and who in after days must confine his ambitions to callings in which human contact is nearly ruled out? There are the host of cripples, victims of infantile paralysis, tuberculous infection, and mechanical accidents. They may learn as well as others how to read and write and cipher (provided their arms are not the site of damage), but what of it if they can not get about and can not use their limbs in any calling? Are they to be a constant source of loss to society as well as weariness to themselves?

Last but not least looms the large number of delicate children well enough equipped otherwise to make much of school life but for whom the conditions of that life (easily met by the ordinary child) are unsafe, to say the least. We refer to those who already at school age have become the prey of the tubercle bacillus to a serious degree. Within a decade after school years it is estimated that (judging by the death rate) about 2 per cent of our population are ill in some degree with tuberculosis, and the relation of this figure to that given for school children showing, by X-ray examination, tuberculosis of the juvenile form is, to say the least, ominous. Tuberculosis, though losing power as a destroyer, still takes 1 out of 12 of us, and, in our best years, 1 out of 5. The loss in life and wealth from this cause is terrific.

The problem for educators is to both conserve the child's life and at the same time make the most of his mental possibilities. The Department of the Interior furnishes to educators everywhere the information, so far as it can be obtained, as to how this can best be done.

But does the schooling we furnish meet the needs of differing children from the mental standpoint? If not, there is bound to be waste. If the child is so constituted that he can not profit by the material or methods of instruction, suitable enough perhaps for the average child, education is a waste for him; and if we do not fit him for the limitations which are bound to be his in later life, his education was a waste from its very vacuity. Besides the child with "subnormal" intelligence there is the so-called delinquent, who, innately, is no worse than his more ordinary brother but who is different and needs to be considered so if we would make the most of him.

|

On the other side of the average is the child of exceptional mentality who may literally "know more than the teacher" and who is in danger of wasting much of his time if that time is not rightly occupied.

But even for the children who do not differ widely from the usual, for that great majority whom we call the average, educators must consider whether, in our changing life, they are wasting their own time and energy and the time and energy of these average children (and so doubly wasting public funds). They are doing so if they do not study and meet the interests and aptitudes of the average child. They are not good conservationists if they do not keep in mind our rapidly changing social conditions and prepare the child accordingly. Education is for life and must keep pace with life. We can not afford to allow the child as he leaves school to step into nothingness rather than into an appropriate niche in the realm of vocational life, for toward some vocation he is inevitably headed.

The information furnished by this department indicates that our ambitions for the child are not always carried out, even in the measurable matter of school attendance. It was estimated in 1926 that of 1,000 children who enter school (and very few who are physically able do not enter) only 768 reach the eighth grade. Many of the 768 do not complete this grade. Of 1,000 children who enter high school only 260 are graduated. The average length of public-school life to-day is just beyond the first year of high school. However, the proportion of children attending high schools has greatly increased in the past 10 years, and the average span of school life per child has very much lengthened.

Still, educators have food for thought and especially for asking whether, in the case of the students who drop out of school before the end of 12 years, the school has fully met the needs of the child. Are we conserving the child or conserving the school? Was the curriculum built around the child or was the child made to fit an outworn program planned without reference to the present-day needs of the child? Or is there a reason outside the school? By a special grant of funds by Congress an intensive study is now in progress of our schools of secondary education which will furnish to those working in this field needed information as to the conservation of youth at this period.

|

| Interest in Food Comes Before Interest in Books |

Granted that the educational needs of the child are fully met as regards what he is taught and how he is taught, there are a multitude of details to be worked out as regards the school plant, its heating, lighting, equipment, the number of pupils per teacher for economy of service, the preparation of teachers, the health of teachers, the length of the school day, of the school term, the school year, the question of summer sessions, of the need for care of children in summer playgrounds or camps. There is the need of careful expenditures in all these matters. Information on all these subjects is collected on a nationwide scale and made available for the school administrator through this department.

|

| The School Nursery Is Becoming Popular |

Until recently formal education was concerned with the child of school age. It was taken for granted that the education of the younger child was adequately taken care of in the home. But the home nowadays is often not a home but only a flat where the young child, often with no playfellows, few playthings, no pets, and no sign of a playground, must shift as best he may for better or worse and often not for the best. The kindergarten was the attempt to meet the needs of children in the year before school age. Dipping deeper into the preschool period, the nursery school has come into existence. While to a large degree experimental in this country, school authorities and parents are widely interested in its possibilities for conserving the young child, who in our modern life finds his environment largely barren of human associations and material resources which meet his normal needs for development. The department furnishes information in this new field.

It is not long since education went on without reference to the home. The child was sent to school for a certain number of days and a certain number of years and that was all there was to the matter, unless the child was especially troublesome to the school. Nowadays education proceeds most effectively and most economically if the constant cooperation of parents is secured. This is especially true as regards education for better health all along the line, from the securing of adequate treatment of diseases and defects discovered at school to adequate feeding and resting. We may inform the child in such matters, but his medical care and hygienic practices are a matter for the home to be interested in, to make possible and encourage. The Parent-Teacher Association with its million and a half of members is ample evidence that the home is responding to the need for cooperation with the school to the end of the conservation of the child.

|

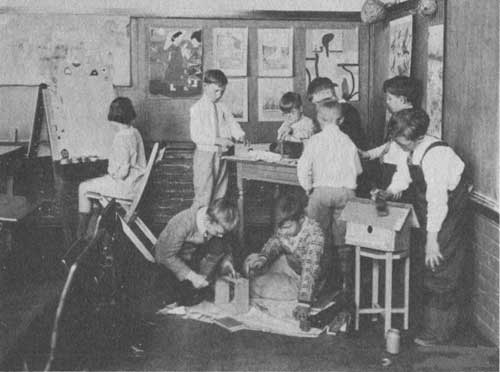

| Education for the Hands |

The parents need information which will aid them in understanding the work of the school and their part in assisting with that work. They need, also, and desire information as to what they can do to make the most of the child's physical, mental, and moral development in the days before he is ready for school, before he can enter the nursery school or the kindergarten. The Office of Education can be looked to as a source of guidance as to where the parent can secure information along these lines.

The whole scheme of education as now set up works to a considerable degree in a virtuous circle for the conservation of our most valuable national asset. It begins with efforts put forth directly by the school to prevent waste and to make the most of the child physically, mentally, and morally. Through instruction and cooperation of parents its endeavors are reinforced and given added impetus. The child of the future will come to the hands of the teacher with a preparation which will involve less expenditure in his schooling, of time, and effort, and of public funds. He will be in better condition to profit by the efforts that are put forth in the school to make of him all that is possible as an individual and as a member of society.

|

| A Happy Family |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

interior-conservation/chap10.htm

Last Updated: 20-Jul-2009