Historical Background

The British Colonials and Progenitors (continued)

THE DUKE OF YORK'S GRANT

Only a few months before the English conquered New Netherland in 1664, Charles II granted the territory as a proprietorship to his brother, James, Duke of York, to hold with all customary proprietary rights. James, keeping for himself the Hudson Valley and the islands in the harbor, renamed the province, as well as the town on Manhattan Island, New York. He conveyed the southern part of his grant, between the Hudson and the Delaware Rivers, to two loyal Stuart supporters, Lord John Berkeley and Sir George Carteret, who named it New Jersey. New York was quickly amalgamated into the English colonial system and enjoyed a continuing prosperity. When James assumed the throne, the province automatically became a royal colony. It was attached briefly to the Dominion of New England, but regained separate status after the Glorious Revolution (1688).

New Jersey had few settlements when it passed into the possession of the new proprietors. A scattering of Swedes, Dutch, and Finns had filtered into the area from New York. Almost as soon as English control was asserted, New England Puritans moved into the area. They were welcomed by the proprietors' representative, who in 1665 founded the village of Elizabethtown. Because immigration into New Jersey was encouraged by promises of religious toleration, representative government, and moderately priced land, the colony was populated rather quickly.

In 1674, Lord Berkeley sold his interest in New Jersey to two English Quakers. From them, it passed into the hands of three others, one of whom was William Penn. In 1676, Carteret agreed with them to split the colony into East and West Jersey and ceded the latter to them. In 1688, James II reasserted his governing right and brought the Jerseys into the Dominion of New England. After the collapse of the Dominion, in 1689, East and West Jersey reverted to full proprietary control. In 1702, however, the proprietors surrendered their governing power to the Crown, but retained their land titles. In 1738, New Jersey was reestablished as a separate royal colony.

In 1682, to obtain access to the seacoast, William Penn acquired Delaware from the Duke of York, who between 1664 and 1680 had taken over the area on the assumption that it was part of his grant and had divided it into three counties, or "Territories." After Penn's purchase, these counties were at first governed as part of Pennsylvania and basked in the same prosperity. In 1701, however, they were authorized to form a separate assembly, which occurred in 1704, and the colony of Delaware was born. But it remained under the jurisdiction of the Penn family until the War for Independence.

PENNSYLVANIA: A QUAKER PROPRIETORSHIP

Pennsylvania was the most successful of the proprietary colonies. Adm. Sir William Penn was a wealthy and respected friend of Charles II. His son, William, was an associate of George Fox, founder of the Society of Friends—a despised Quaker. When the senior Penn died, in 1670, his Quaker son inherited not only the friendship of the Crown but also an outstanding unpaid debt of some magnitude owed to his father by the King. In settlement, in 1681 he received a grant of land in America, called "Pennsylvania," which he decided to use as a refuge for his persecuted coreligionists. It was a princely domain, extending along the Delaware River from the 40th to the 43d parallel. As proprietor, Penn was both ruler and landlord. The restrictions on the grant were essentially the same as those imposed on the second Lord Baltimore: colonial laws had to be in harmony with those of England and had to be assented to by a representative assembly.

|

| "The Landing of William Penn, 1682." From a painting by J. L. G. Ferris. (Courtesy, William E. Ryder and the Smithsonian Institution.) |

Penn lost little time in advertising his grant and the terms on which he offered settlement. He promised religious freedom and virtually total self-government. More than 1,000 colonists arrived the first year, most of whom were Mennonites and Quakers. Penn himself arrived in 1682 at New Castle and spent the winter at Upland, a Swedish settlement on the Delaware that the English had taken over; he renamed it Chester. He founded a capital city a few miles upstream and named it Philadelphia—the City of Brotherly Love. Well situated and well planned, it grew rapidly. Within 2 years, it had more than 600 houses, many of them hand some brick residences surrounded by lawns and gardens.

Shiploads of Quakers poured into the colony. By the summer of 1683, more than 3,000 settlers had arrived. Welsh, Germans, Scotch-Irish, Mennonites, Quakers, Jews, and Baptists mingled in a New World utopia. Not even the great Puritan migration had populated a colony so fast. Pennsylvania soon rivaled Massachusetts, New York, and Virginia. In part its prosperity is attributable to its splendid location and fertile soils, but even more to the proprietor's felicitous administration. In a series of laws—the Great Law and the First and Second Frames of Government—Penn created one of the most humane and progressive governments then in existence. It was characterized by broad principles of religious toleration, a well-organized bicameral legislature, and a forward-looking penal code.

|

| A group of Cherokee Indians brought to London in 1730 by Sir Alexander Cuming. From an engraving by Isaac Basire, after a painting by Markham, in the British Museum. (Courtesy, Smithsonian Institution.) |

|

| Symbolic scene representing the various treaties William Penn negotiated with the Indians in Pennsylvania. The Indians admired Penn because he dealt fairly with them in land transactions and protected them. From an engraving by John Hall, 1775, after a painting by Benjamin West. (Courtesy, Library of Congress.) |

Another reason for the colony's growth was that, unlike the other colonies, it was not troubled by the Indians. Penn had bought their lands and made a series of peace treaties that were scrupulously fair and rigidly adhered to. For more than half a century, Indians and whites lived in Pennsylvania in peace. Quaker farmers, who were never armed, could leave their children with neighboring "savages" when they went into town for a visit.

By any measure, Penn's "Holy Experiment" was a magnificent success. Penn proved that a state could function smoothly on Quaker principles, without oaths, arms, or priests, and that these principles encouraged individual morality and freedom of conscience. Furthermore, ever a good businessman, he made a personal fortune while treating his subjects with unbending fairness and honesty.

|

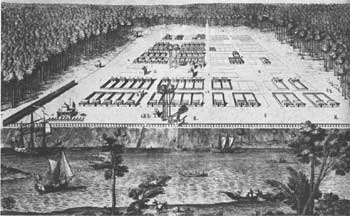

| Savannah, in 1734, the year after James Oglethorpe founded the city and colony of Georgia. From an engraving by P. Fourdrinier, after an on-the-scene drawing by Peter Gordon. (Courtesy, Library of Congress.) |

GEORGIA—EARLY PENETRATION

By 1700, the last of the British colonies in the present United States, Georgia, had not yet been founded. Not until 1733 did the philanthropist Gen. James Oglethorpe begin to settle the colony, which he had conceived as a refuge for oppressed debtors in English prisons [Colonials and Patriots, Vol. VI in this series, pp. 19-20]. As the 17th century neared an end, however, the British were beginning to penetrate the area. English traders set up posts on the Savannah, Oconee, and Ocmulgee Rivers and were active along the Chattahoochee and as far west as the Mississippi. Winning the friendship of two powerful Indian tribes, the Creek and the Chickasaw, they created the antagonism with the Spanish and the French that resulted in the international clashes of the early 1700's.

|

| James Oglethorpe, founder of the colony of Georgia, presents Tomochichi, chief of the Yamacraws, to the Lord Trustees of the colony, in England. Oglethorpe, wearing a black suit, stands in the center. From a painting by William Verelst, 1734. (Courtesy, Smithsonian Institution.) |

SOCIAL AND CULTURAL LIFE

Life in early colonial times was harsh, and the refinements of the mother country were ordinarily lacking. The colonists, however, soon began to mold their English culture into the fresh environment of a new land. The influence of religion permeated the entire way of life. In most southern colonies, the Anglican Church was the legally established church. In New England, the Puritans were dominant; and, in Pennsylvania, the Quakers. Especially in the New England colonies, the local or village church was the hub of community life; the authorities strictly enforced the Sabbath and sometimes banished nonbelievers and dissenters.

Unfortunately, the same sort of religious intolerance, bigotry, and superstition associated with the age of the Reformation in Europe also prevailed in some of the colonies, though on a lesser scale. In the last half of the 17th century, during sporadic outbreaks of religious fanaticism and hysteria, Massachusetts and Connecticut authorities tried and hanged a few women as "witches." Early in the 18th century, some other witchcraft persecution occurred, in Virginia, North Carolina, and Rhode Island. As the decades passed, however, religious toleration developed in the colonies.

Because of the strong religious influence in the colonies, especially in New England, religious instruction and Bible reading played an important part in education. In Massachusetts, for example, a law of 1647 required each town to maintain a grammar school for the purpose of providing religious, as well as general, instruction. In the southern colonies, only a few privately endowed free schools existed. Private tutors instructed the sons of well-to-do planters, who completed their educations in English universities. Young males in poor families throughout the colonies were ordinarily apprenticed for vocational education.

By 1700, two colleges had been founded: Harvard, established by the Massachusetts Legislature in 1636; and William and Mary, in Virginia, which originated in 1693 under a royal charter. Other cultural activities before 1700 were limited. The few literary products of the colonists, mostly historical narratives, journals, sermons, and some poetry, were printed in England. The Bay Psalm Book (1640) was the first book printed in the colonies. Artists and composers were few, and their output was of a relatively simple character.

|

|

http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/explorers-settlers/intro28.htm

Last Updated: 22-Mar-2005