|

Geological Survey Bulletin 611

Guidebook of the Western United States: Part A |

ITINERARY

|

|

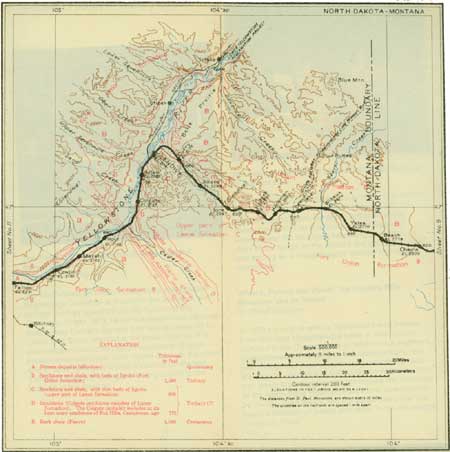

SHEET No. 10. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

|

Beach, N. Dak. Elevation 2,779 feet. Population 1,003. St. Paul 626 miles. |

Beach (see sheet 10, p. 68) is one of the towns that have recently grown up as a result of the successful farming of this region. West of Beach the railway crosses the State line into Montana, a little west of milepost 176. The position of the State line is indicated by a sign on the left of the track.

|

Montana. |

The State of Montana has an area of 146,572 square miles, or a little more than that of the States of New York, New Jersey, Delaware, Pennsylvania, and Ohio. It was admitted to the Union in 1889 and according to the census of 1910 had a population of 376,053. Montana has long been known as a metal-producing State, and many have thought of it as being entirely mountainous and as suited only for mining. As a matter of fact, the western half alone is mountainous; the eastern half, an area nearly as large as North Dakota, is in the Great Plains.

Although placer gold was discovered in Montana in 1852, it was not until 10 or 12 years had elapsed that the "gold rush" began and the outside world was made acquainted with the wondrous wealth of its mountain gravel. Many persons starting for the new gold diggings stopped in the more promising valleys, such as the Gallatin and the Bitterroot, and farming began almost as soon as the panning of gold. The mining industry of the State has passed through a number of changes from placer mining to lode mining of gold and silver and, finally, of copper as the leading metal. Before the development of the great copper mines at Butte, Michigan was the leading State in the production of copper, but it soon gave place to Montana, which for a number of years stood at the head. Recently Arizona has forged to the front and Montana has dropped to second place in the rank of copper producers. Despite the fact that Montana ranks second in the amount of copper produced annually, it still is first in the total amount produced. The total for the three leading States up to the close of 1913 is as follows: Montana, 3,214,775 tons; Michigan, 2,759,721 tons; Arizona, 2,324,719 tons.

At first agriculture flourished only in the mountain valleys, where there was protection from the frost and the wind, and the plains portion of the State was devoted to the grazing of stock. Immense herds of cattle roamed the plains, and for a number of years Montana held first place in the number of sheep and the value of the wool shipped out of the State. Irrigation was finally undertaken in many of the valleys, and large crops of wheat, oats, alfalfa, and sugar beets are now being raised. The most recent change has been the influx of the dry-land farmer and the taking up and fencing of most of the land in the eastern and central parts of the State. This has materially decreased the number of live stock, and in the sheep industry Montana has dropped to second place, Wyoming taking the lead. Dry farming has not been universally successful, but sufficient has been accomplished to demonstrate that it is feasible when rightly carried on and with sufficient capital to enable the farmer to tide over years of drought and crop failure. The most important crop in the State is forage, amounting in 1909 to over $12,000,000.

Probably few persons realize that the value of manufactured articles in Montana exceeds that of the output of the mines, but such is the case. The smelting and refining of copper are the leading industries, but the value of the manufactured product is not given in the census reports. It is, however, roughly the same as the output of the mines. Aside from the manufacture of copper, the leading manufacturing industry is that of lumber and timber, which in 1909 amounted to over $6,000,000. The values of the products of the State, exclusive of the copper smelted and refined, are about as follows: Manufacturing (1909), $73,000,000; mining (1913), $69,000,000; agriculture, (1909), $63,000,000.

|

Wibaux, Mont. Elevation 2,674 feet. Population 487. St. Paul 636 miles. |

The country continues to be rolling to the valley of Beaver Creek, a tributary of Little Missouri River, on which is situated the town of Wibaux (we'bo), in the midst of an excellent farming district. Four miles west of Wibaux the railway crosses the summit between the drainage basin of Little Missouri River on the east and that of Yellowstone River on the west, and then begins a long descent down Glendive Creek to the Yellowstone. This valley was a famous hunting ground in early days, and the name Glendive was applied to it by Sir George Gore, an Irish nobleman, who hunted buffalo here in the winter of 1855-56.

The rocks, which to the eye appear to be horizontal, in reality rise steadily toward the southwest as part of a broad and gently curved arch in the strata, more fully described on page 68. The rise of the rocks in this direction brings to the surface those crossed in the badlands east of Medora and others that lie below the level of Little Missouri River at that place, but the country is so generally grass covered that the traveler can not see them all.

At Hodges there is a bed of lignite which is supposed to mark the base of the Fort Union formation, and may be the same as the bed reported to be 23 feet thick under Medora. The rocks below this bed, which are scarcely distinguishable from the rocks above, belong to the Lance formation, in which the valley of Glendive Creek is cut from Hodges to Yellowstone River. In most places the valley is bounded by bare walls of somber-colored rocks and subdued badlands, but they are neither so imposing nor so picturesque as those of Pyramid Park. The Lance formation carries some beds of lignite, but generally they are too thin to mine.

|

Allard. Elevation 2,269 feet. St. Paul 657 miles. |

Below Allard the Lance formation constitutes the valley walls as far as Yellowstone River. Along this part of the valley no two of the topographic forms are the same, but there is a similarity of type and color that soon becomes extremely monotonous. There are, however, some well-defined terraces which in a measure tend to relieve the dullness of the landscape. The upper terrace probably records an epoch when the stream was flowing at a higher level than it is to-day, these terraces being remnants of the old valley floor. The lower terraces, which are well developed near the river, may record flood stages of the Yellowstone, when slack water from the river backed up into all the tributary valleys and caused sand and mud to be deposited.

|

Glendive. Elevation 2,091 feet. Population 2,428. St. Paul 667 miles. |

At milepost 213 the train swings out from the mouth of Glendive Creek into the broad valley of the Yellowstone and in a few minutes reaches Glendive, the end of the division the county seat of Dawson County, and one of the largest towns in eastern Montana. In building the main line of the Northern Pacific Railway in 1879-80 this was the most important town between Missouri River and Helena, for it was the point from which construction was carried on in both directions. This was made possible by the transportation of supplies from Bismarck by way of Missouri and Yellowstone rivers. When through travel was established, however, Glendive lost most of its importance, and for a long time its growth was slow, as the country roundabout was but sparsely settled and its principal business was that of a division terminal of the railroad. Recently, with the impetus given to agriculture by the introduction of dry-farming methods and with the completion of the Lower Yellowstone irrigation project by the United States Reclamation Service,1 settlers have flocked in, and the country which 10 years ago was an open range is now almost all cut up into small farms. This change has removed from this region one of the picturesque types of western life—the "cow-puncher" of the early days. The traveler may still see a few poor imitations or caricatures, but the real article—the fearless, daredevil rider who was an equally fearless "booze fighter" when he came to town—is no more. The big herds are gone, and with them the men who tended them.

1In the Yellowstone Valley in eastern Montana, tributary to the Northern Pacific and Great Northern railways, the Government has built an irrigation system to cover a strip of land 70 miles long lying on both sides of the river and extending over the boundary line into North Dakota. The irrigable area consists of about 60,000 acres of land lying in the midst of one of the best and largest grazing areas in the United States.

The soil is a deep sandy loam and when properly cultivated produces abundant crops of hay and grain. Alfalfa, the great forage crop of the West, grows to perfection here, and dairying and the winter feeding and fattening of stock are profitable industries.

The towns of Intake, Burns, Savage, Craneville, Sidney, and Fairview, Mont., and Dore, N. Dak., are in the area covered by the project. Nearly all the Government lands have been filed upon, but several hundred farms are for sale on easy terms and at reasonable prices. The cost of water right is $45 an acre, payable in annual installments to the Government.

The general elevation is 1,900 feet above sea level, and the temperature ranges from 30° below to 100° above zero. The advantages of the valley in the way of fertile soil, assured water supply, favorable climate, low prices, and transportation facilities make it one of the most desirable locations in the Northwest.

At Glendive the railway route again touches the trail of Lewis and Clark, for in their homeward journey Capt. Clark with a small party descended Yellowstone River.2 As nearly as can be determined, they passed the site of Glendive on August 1, 1806.

2The name Yellowstone was doubtless given to the river because of some outcrop of yellow rocks along its banks; but where do such rocks occur? The traveler in passing up the valley sees no distinctly yellow rocks between Glendive and Livingston, and if he goes to Yellowstone Park he will see none as far as Gardiner, the northern entrance to the park. With in the park the conditions are different. The canyon of the Yellowstone below the falls is noted the world over for its gorgeous display of colors, among which the most brilliant and dominating tint is yellow. Here is the only place on the river where the rocks are so distinctly yellow as to have suggested a name for the stream, and the conclusion seems inevitable that here the name originated.

As the evidence available seems to indicate that the name did not originate with the English explorers, it must have been given by some early French traveler or by the Indians who inhabited the region. The only Frenchman who is thought to have seen the upper part of the Yellowstone Valley before the time of Lewis and Clark was Verandrye, who, between the years 1738 and 1742, penetrated the wilderness far to the west of Lake Winnipeg and who wandered for a long time among the mountains in an ineffectual attempt to reach the Pacific slope. It is said that he reached the headwaters of the Missouri and even penetrated as far south as the central part of Wyoming, where he was so beset by hostile Indians that he was forced to return to the east.

None of the points described by Verandrye have been recognized, so the identity of the country which he traversed will always remain a matter of doubt. It seems incredible, however, that he should have visited the site of the present Yellowstone Park without noting at least some of the wonderful geysers and hot springs. On this negative evidence it is reasonable to conclude that he did not visit the canyon of the Yellowstone, and therefore that the Indians were the first people to apply the name.

South of Glendive there can be seen on the left (east) badland bluffs and on the right the muddy river, which, a short distance above the town, is crossed by the new branch railway leading to Intake and other towns established under the Lower Yellowstone irrigation project. Still farther south the railway passes through deep cuts in massive white sandstone and skirts a prominent pinnacle of the same rock, known as Eagle Butte. This white sandstone with a buff layer at the bottom is known to geologists by the local name of Colgate sandstone. The lower part contains in places casts of sea weeds and marine shells, so that it is believed to represent the sandy shore of an ancient sea. It is supposed to be in part equivalent to the Fox Hills sandstone of South Dakota. The rocks overlying the Colgate sandstone in this region are all of fresh-water origin. At Eagle Butte the sandstone appears to be nearly horizontal, but it rises gently toward the southwest and near milepost 7 it is high in the hills, and the shale below it appears at railroad level. The hill near milepost 7, known as Iron Bluff, is noted for the beauty and abundance of the fossil shells that occur in limestone concretions1 in the dark shale. The shells are so perfectly preserved that they retain their pearly luster. From the kinds of shells occurring in the shale and from its character it is known to be the same as the dark shale that is poorly exposed in the river bluffs at Valley City, N. Dak. It is called the Pierre shale and is of Upper Cretaceous age. The fossil shells show clearly that the sea must have occupied this part of the country when the shale was deposited. At that time, instead of rolling prairies across North Dakota and eastern Montana, there were rolling waves and abundant marine life.

1The term concretion is applied to rounded bodies of rock that are somewhat harder and more resistant than the main mass of the formation in which they are contained and for that reason remain on the surface after the rest of the formation has decayed. In many places they are nearly spherical, but as a rule they are irregular in outline, either elongated in a mass resembling the trunk of a tree or flattened like a disk.

The material composing concretions differs greatly; in sandstone or sandy shale it is generally sand, or sand containing a large amount of iron; in limestone it is generally chert (a form of silica); in shale it consists of limestone or ironstone.

The concretions of Iron Bluff are doubly interesting because they are made up almost exclusively of fossil shells. It seems probable that the shells grew in colonies and thus provided the lime of which the concretions are composed. The result is very beautiful and many of the coiled shells are so perfect that they might inspire another Holmes to write a poem on the chambered nautilus of the ancient sea.

The Pierre shale continues to Cedar Creek, 11 miles beyond Glendive, where, if the traveler looks ahead on the left at milepost 11, he will see on the far side of the valley a large ridge in which the rocks dip as much as 20° in the direction in which he is going, the opposite direction from their dip between Glendive and Cedar Creek. In other words, the train has crossed a great arch or anticline in the rocks, the highest point of which is at Cedar Creek. The Glendive anticline is the most pronounced fold in eastern Montana. It extends from Yellowstone River in a straight line southeastward into the extreme northwest corner of South Dakota. It brings to the surface the Pierre shale on the center of the arch, and as this shale is softer than the rocks on either side, it gives rise to a belt of country having little relief. For this reason it was followed by the Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul Railway from Marmarth, N. Dak., to Baker, Mont. The shale is everywhere rimmed about by the hard Colgate sandstone, and this in turn by the Lance and Fort Union formations. The form of this fold is shown in figure 7, which represents the strata as they would appear if the observer were in an airplane hovering over the flat on the far side of the river and looking up the valley of Cedar Creek to the southeast. A short distance beyond the mouth of the creek the steep dips die out and the rocks are so nearly flat that they seem to be horizontal.

|

| FIGURE 7.—Diagram of Glendive anticline, Mont., looking east. Gentle dips on northeast side; steep dips on southwest side. |

At milepost 17, between Hoyt and Marsh, there is a large gravel pit on the left from which ballast has been hauled as far east as Richardton, N. Dak. This gravel, as well as that occurring at other places along the river, contains many moss agates which have been washed down from the mountains in the vicinity of Yellowstone Park, and many fine specimens have been picked up along the track.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

bul/611/sec11.htm

Last Updated: 28-Mar-2006