|

Geological Survey Bulletin 611

Guidebook of the Western United States: Part A |

ITINERARY

|

|

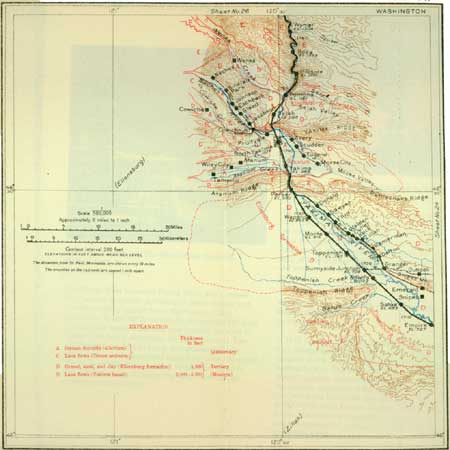

SHEET No. 25. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

|

Alfalfa. Elevation 723 feet. Population 81.* St. Paul 1,717 miles. |

After passing Empire (see sheet 25, p. 176), Satus, Toppenish Ridge, and Alfalfa the traveler can get a full view of Mount Adams, far to the west. Although it is here more than 50 miles distant, its great height (12,307 feet above sea level) makes it conspicuous. (See Pl. XXIII, p. 167.) To one unaccustomed to judging of the magnitude of distant mountains, the first view of Mount Adams may be disappointing, but after watching it for some time and comparing it with objects near by the observer will find that its enormous bulk becomes more apparent. How cold it seems in its eternal pall of white! The mountain looks like some patrician of old, holding himself erect and aloof from all surroundings! Long ago it was an active volcano emitting molten lava, but its activity ceased, and for unknown ages the mountain has stood the cold, calm, rugged peak it is to-day. Just beyond Mount Adams and from many points of view hidden by it is Mount St. Helens, which within the memory of the white man has showed signs of volcanic activity. It is apparent that the volcanoes of the Cascade Range, while possibly extinct, have not been so for a great length of time. That they may be only smoldering is indicated by the recent outburst of Lassen Peak, in California, which stands along the same line of volcanic disturbance.1 Mount Adams remains a magnificent spectacle, until the view of it is shut off by the Atanum Ridge, north of Parker. Although the country about Toppenish lies within the Yakima Indian Reservation, it is well watered by ditches that receive their supply from the river in the vicinity of the next ridge, which can be seen in the distance. The land is well cultivated, though not so intensively as that covered by the Sunnyside reclamation project across the river.

1The view from Alfalfa or Toppenish gives to the traveler an excellent idea of the height and character of the Cascade Range and of the volcanic cones which project above its apparently even crest line. In order, however, to understand fully the relations of those cones and the character of topography of the platform upon which they are built, it is necessary to know something of the geologic history of the range and of the conditions which have tended to produce its present form.

After the great lava sheets were spread out and somewhat deformed by folding, the region was subject to the action of the elements, and the rain and streams reduced the surface to a nearly uniform plain only a slight distance above sea level. From this plain the present Cascade Range was formed by a gradual uplift of the surface along the axis of the mountains. This upward movement continued until the surface was raised to a height of 4,000 feet above sea level in the south and about 8,000 feet in the north, In this uplifted mass the streams carved deep channels or canyons, almost destroying the plateau and leaving only the high summits to mark its once even surface. When seen from a distant point, as from Toppenish, the tops fall into line and have the appearance of an unbroken upland mass.

At the same time that the streams were engaged in trenching the mountains, vents were formed here and there along the range, through which ash and lava reached the surface and were deposited on the platform of the range. As lava flow succeeded lava flow, and showers of ash fell upon the area surrounding the vent, a cone was gradually built up, forming the present high peaks. These volcanic cones between Canada and Columbia River are Mount Baker, Glacier Peak, Mount Rainier (Tacoma), Mount Adams, and Mount St. Helens.

The view from Alfalfa or Toppenish shows clearly that Mount Adams rests on the platform called the Cascade Range, but that it is not really a part of that range, but rather an excrescence upon the apparently rounded, tree-covered surface of the plateau.

|

Toppenish. Elevation 765 feet. Population 1,598. St. Paul 1,721 miles. |

While enjoying the beautiful spectacle of Mount Adams, the traveler should look a little farther to the north where, if the atmosphere is clear and no cloud banners intervene, he may be fortunate enough to catch a view of the summit of Mount Rainier (Tacoma), 14,408 feet in altitude, the highest peak of the Cascade Range, but this view gives him little idea of the magnitude and grandeur of the mountain.

|

Wapato. Elevation 865 feet. Population 400. St. Paul 1,729 miles. |

The great sheets of basalt that underlie the Yakima Valley are in places thrown into low folds by pressure in the crust of the earth exerted in a north-south direction, and consequently the folds trend at right angles to that direction, or nearly east and west. As these folds bring up the hard basalt, they make ridges or mountains across the country, the length of the ridge depending on the the extent of the fold. The big ridge lying to the south of the railway from Kennewick to Mabton is supposed to be of this character, although its structure has not been accurately determined. This broad upland, from its original cover of abundant and nutritious bunch grass, is known as Horse Heaven. The next ridges to the north are Toppenish Ridge west of the river and Snipes Mountain on the east. These appear to be parts of one general line of disturbance but are separate folds. In Snipes Mountain the arch is so low that the basalt is scarcely visible under the cover of the Ellensburg formation.

|

Parker. Elevation 930 feet. Population 823.* St. Paul 1,733 miles. |

The next anticline to the north, which lies north of Toppenish, is known west of the river as Atanum Ridge and east of the river as Rattlesnake Ridge. The Yakima has made a deep, narrow cut, called Union Gap, through this ridge north of Parker. At the south entrance to the gap the Northern Pacific crosses the North Yakima branch of the Oregon-Washington Railroad. The gap is about a mile in length, and the sheets of lava at the south entrance dip toward the south at an angle of about 20° The opposite dip on the north side of the fold is not so apparent, for it is much steeper and in some places the layers are crushed and overturned, so that the dip is toward the south.

In a region in which the annual precipitation is so small (8.9 inches) as it is in the Yakima Valley the quantity of water flowing in the streams and available for irrigation is of the utmost importance. In order to determine the volume of water in Yakima River the United States Geological Survey maintained for a number of years a gaging station in Union Gap, but for the last six years the station has been near Wapato, a few miles below the gap. By means of a small car swinging from a steel cable the engineer is able to measure the velocity of the current at a number of points across the stream, and from these measurements, together with other measurements of the cross section of the river, compute the volume of water available for irrigation and the development of power.1

1A gaging station has been maintained in this vicinity since November, 1896. It shows a mean annual flow of 4,640 second-feet (a second-foot means 1 cubic foot per second), which equals 3,360,000 acre-feet (an acre-foot is 43,560 cubic feet, or the quantity required to cover 1 acre to the depth of 1 foot).

About 1,500 river-measuring stations similar to the one at Union Gap are now maintained by the United States Geological Survey on the more important streams in the United States and in the Hawaiian Islands. The data collected at these gaging stations are of prime importance in developing the water resources of the country and are used in designing and operating power and irrigation plants, city waterworks, and other works whose establishment and successful operation depend on a knowledge of the quantity of water flowing in surface streams.

North of Union Gap the valley broadens into a parklike country, all of which is under irrigation and highly cultivated, except near the river, where the land is excessively wet. The original Yakima City was situated just above Union Gap, and the station, the only remaining structure on the site, can be seen near milepost 86. Trouble arose between the railway and the town promoters and the station was abandoned, and a new station, called North Yakima, established about 4 miles north of the old one. With the growth of the new town of North Yakima the older settlement soon died out.

|

North Yakima. Elevation 1,076 feet. Population 14,082. St. Paul 1,741 miles. |

North Yakima is the largest town in central Washington and is the commercial and social center of the Yakima Valley, one of the largest areas of irrigated land in the West and, one that is noted the world over for the fine fruit which it produces. The valley, although semiarid,2 is well supplied with water from Yakima River and its tributary, Naches River, both of which head in the Cascade Range, where the snowfall is abundant. Fruit raising is the principal occupation, but there are also broad fields of grain, alfalfa, and hops, indicating that the farmers feel the necessity of a diversity of crops, so that in case of an oversupply of one they will have another to fall back upon.

2According to the United States Weather Bureau, the mean annual precipitation in the Yakima Valley from 1893 to 1903 was 8.9 inches, divided as follows: Winter, 4 inches; spring, 2 inches; summer, 0.7 inch; autumn, 2.2 inches.

The volcanic rocks that border the Naches Valley and extend within a few miles of North Yakima furnish an interesting example of a recent lava flow. The hummocky surface of this plateau between Naches River and Cowiche Creek, although in places covered by sagebrush and bunch grass, exhibits the essential features of a cooling lava flow, and at many points on its borders the characteristic jointing due to contraction on cooling is shown in rare perfection. (See Pl. XXIV, B.)

|

| PLATE XXIV.—A (top), YAKIMA CANYON, WASH. The hard basalt rapidly breaks down under the influence of the weather, and the broken fragments largely conceal the underlying rocks. B (bottom), COLUMNAR ANDESITE NEAR YAKIMA CANYON, WASH. |

North of North Yakima the railway crosses Naches River and then passes through Yakima Ridge in a short canyon cut in the thick layers of basalt, which have here, as in the other ridges to the south, been folded into a low anticline.1

1After having traveled up Yakima River for nearly 100 miles and passed through a number of basalt ridges, the traveler may be surprised at the apparent disregard of the stream for the ridges and valleys. As stated previously, the principal arches and troughs into which the rocks have been bent trend in a nearly east-west direction, and if the streams followed similar courses they would encounter little difficulty in reaching their destinations. But instead of following the synclinal valleys Yakima River flows almost due south and crosses in this part of its course no less than seven ridges of arched or upturned basalt. What made the stream select its present course, and why did it persist in this course across the arches of hard rock when it might have found an outlet to the Columbia on the east by an open synclinal valley?

In order to answer this question it will be necessary to go back in imagination to a time before the ridges were formed, when the Ellensburg formation (sand, gravel, and volcanic ash) was laid down in a shallow lake on the Yakima basalt. Finally the lake was filled or there was an uplift of the region which changed it to a land area. Over this newly made land streams flowed down the slope on their way to the sea. In this epoch Yakima and Columbia rivers were formed, before the great arches in the rocks had been produced. After the streams were well established, in about the same courses that they follow today, a great north-south pressure wrinkled the rocks into a series of broad, shallow troughs and rather short arches. Many persons think of such a movement as having occurred suddenly and as having crumpled the rocky layers as leaves of paper may be crumpled in the hand. If the movement had been sudden, then the southward-flowing stream would have been dammed wherever one of the arches crossed its pathway, and Yakima River, instead of flowing as it does to-day, would have been broken into a number of separate streams, each of which would probably have found an outlet to the east into Columbia River. As this did not happen, it seems evident that the movement was not rapid, but was so slow that the stream cut the rock away as fast as it was forced up. As the downward cutting of a stream in hard rocks is done very slowly, it follows that the arching of the strata must also have been a very slow process, probably occupying thousands of years. Although the movement was slow, it persisted until some of the arches attained an altitude of 2,000 or 3,000 feet; but the stream maintained its course and now presents the apparently anomalous feature of cutting directly through ridge after ridge, disregarding the structure or topography of the region.

|

Selah. Elevation 1,108 feet. Population 1,524.* St. Paul 1,744 miles. |

The canyon is short and north of the ridge lies Selah Valley, one of the prettiest valleys in this part of the country. The land is rolling or even hilly along the sides of the valley, but water is carried in a high-line canal, so that all the hills and slopes below it are highly cultivated, and orchards extend as far as the eye can see. The basalt dips under the valley, but a little farther north it rises above water level, and the river has cut a sharp canyon with vertical walls from 50 to 70 feet high. The main canyon, which begins near milepost 99 (see Pl. XXIV, A) is cut through three separate but parallel ridges of basalt, each of which was produced by a low up-arching of the lava, as shown in figure 36. At the entrance to the deeper part of the canyon the great sheets of lava, each representing an individual flow, rise more steeply toward the north, their dip (20° or 25°) corresponding in a general way with the south slope of the ridge. The walls of the canyon increase in height until at milepost 103, where the railway crosses the river, they are nearly 2,000 feet high. Here the rocks are about horizontal, indicating that this is the middle (axis) of the fold, from which the beds dip in opposite directions. North of the axis the layers of basalt dip 30° or 35° to the north.

|

| FIGURE 36.—Fold in basalt north of Roza, Wash., as seen from a point near Wymer, looking southeast. |

The northward dip continues to Roza, near milepost 106, where two lateral valleys entering on opposite sides of the river mark the depression or trough between the ridges. Toward the east the ridge south of Roza extends for a long distance, but in the other direction it dies down rapidly, and in a distance of 5 or 6 miles has disappeared.

|

Roza. Elevation 1,258 feet. St. Paul 1,756 miles. |

Beyond Roza the beds of lava rise northward about 30° up the slope of Umptanum Ridge, which is a few hundred feet higher than the one south of Roza. The axis of the fold is reached about milepost 109, and beyond this point the beds can be seen to bend over in a great arch; but the traveler is so close to the rocky wall that it is impossible for him to obtain a satisfactory idea of the size or shape of the fold until he has gone some distance past it. At Wymer siding, between mileposts 110 and 111, a good view of the fold on the east side of the river can be obtained by looking directly back from the rear of the train. (See fig. 36.) From this point the fold is seen to be unsymmetrical, with the steepest dips on the north side.

All the lava folds crossed so far in the Yakima Valley are either steepest on the north side or overturned, like that of Atanum Ridge at Union Gap. This overturning toward the north indicates that when the folds were produced the thrust came from the south, and it continued not only until the beds were arched but until the arch was pushed over, so that the beds on the north side stand nearly vertical or dip steeply toward the south. The northern limit of this fold is marked by the valley of Umptanum Creek (see sheet 26, p. 186), which enters the river near milepost 114.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

bul/611/sec26.htm

Last Updated: 28-Mar-2006