|

Geological Survey Bulletin 612

Guidebook of the Western United States: Part B |

ITINERARY

|

|

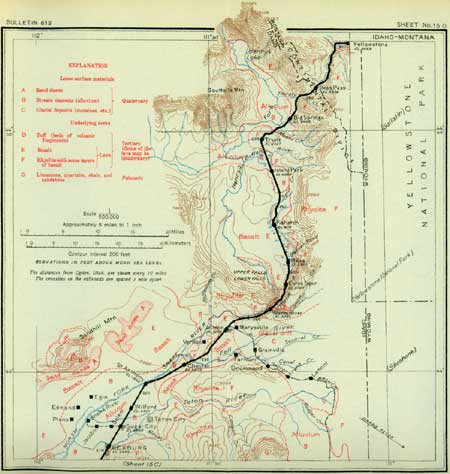

SHEET No. 15D. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

|

Rexburg. Elevation 4,866 feet. Population 1,893. Ogden 210 miles. |

Rexburg (see sheet 15D, p. 148) was founded in 1883 by Thomas Ricks, and the present name is a corruption of Ricksburg. Up to 1896 Rexburg was composed mostly of one-story dirt-roofed houses, but it is now a prosperous and well-appointed village, the county seat of Madison County, and the center of an irrigated agricultural district where crops never fail. Seed peas constitute one of the important crops. The produce forwarded from Rexburg in the 15 months between January 1, 1913, and April 1, 1914, was: Grain, 679 cars; flour, 256 cars; sugar beets, 226 cars; live stock, 190 cars; miscellaneous, 92 cars; total, 1,443 cars. Rexburg station is built of the local rhyolite or pink lava. Soon after leaving Rexburg the train crosses Teton River,1 which drains Teton Basin and the west flank of the Teton Mountains.

1At the mouth of its canyon, a few miles east, Teton River has a mean discharge of about 900 second-feet. The maximum and minimum discharges recorded are 7,620 and 88 second-feet. There is a small hydroelectric power plant on this stream.

|

Sugar City. Elevation 4,890 feet. Population 391. Ogden 214 miles. |

Sugar City is a settlement around a beet-sugar factory which was built in 1904 at a cost of $750,000. This factory contracts for the beets from about 7,000 acres and pays $5 a ton for them. A branch of the railroad runs west from Sugar City to Plano, tapping the lower end of the Egin bench, a celebrated and prosperous farming district on the west side of Henrys Fork.

Four miles northeast of Sugar City is Teton City, a village of a few hundred people on the bank of Teton River, in the midst of grain and pea ranches. This settlement also was founded by Mormons, in 1883. The gently sloping hills from Teton City east to Canyon Creek are made up of rhyolite interbedded with a few thin layers of hard black basalt. The alternate layers of two different kinds of lava in these hills show that in the time of volcanic activity in this part of the country thick flows of rhyolite were succeeded by lesser flows of black lava. That the flows were separated by lapses of considerable time is shown by the presence of layers of soil between them. In a deep well hole sunk in the lava several miles east of Teton City the drill passed through a number of layers of soil between beds of basalt and rhyolite. One bed of soil was encountered at a depth of 400 feet.

A few miles north of Sugar City is a railroad siding known as Wilford. St. Anthony, the county seat of Fremont County, is hidden in the trees ahead. The building with a white dome seen on the left on entering the town is the county courthouse, and the large gray building just beyond the station is a Mormon temple.

|

St. Anthony. Elevation 4,969 feet. Population 1,238. Ogden 221 miles. |

The location of St. Anthony, like that of Idaho Falls, was determined by the fact that the river has here cut a narrow canyon through basalt, with walls so close together that a bridge was easily built. Previous to 1893 this place included only "jack rabbits, lava rock, and Old Man Moon." C. H. Moon, the original settler, came here in 1887, built the first bridge and store, and called the place St. Anthony because of its fancied resemblance to St. Anthonys Falls, Minn. The river in the canyon has a fall of about 30 feet, and the walls at the highway bridge are barely 50 feet apart. Immediately below the bridge the river spreads out to an extreme width of 800 feet.

In the spring of 1893, when St. Anthony was made the county seat of Fremont County, the settlement consisted of three log cabins and one two-story log store building. The population increased rapidly from that date and now numbers about 2,000 persons. St. Anthony has two large schoolhouses, one of which cost $60,000, a $70,000 courthouse, an opera house, a large flouring mill, grain elevators, three banks, and a city water system supplied by pumping with electric power generated by Snake River.

One of the principal industries in the immediate vicinity of St. Anthony is the raising of seed peas. In 1913 there were 26,000 acres of seed peas in Fremont County. They are grown here extensively because the soil and climate are favorable, and under irrigation they yield heavily. There are nine seed warehouses in St. Anthony. The shipments from St. Anthony for the year 1913 were 396 cars of peas, 470 cars of oats, 259 cars of wheat, 10 cars of barley, 50 cars of potatoes, 106 cars of merchandise, 121 cars of stock, 52 cars miscellaneous; total, 1,464 cars. Thousands of head of stock are wintered in this vicinity each year after summering in the mountains.

As the train leaves the station a glimpse is had of Henrys Fork of Snake River. Twelve miles west of St. Anthony a group of hills known as the Sandhill Mountains rise about 1,000 feet above the plain. From a distance they appear to be two lines of hills with nearly parallel tops, but on entering the gap between these lines of hills one finds a cultivated valley surrounded on three sides by a ridge, the crest of which has rudely the outline of a mule shoe. The lava that caps this ridge slopes away on all sides from the central valley. This group of hills apparently is the broken-down remnant of an old crater. A great mass of yellow sand, drifted in from the southwest, is lodged in the north side of the crater.

Sand dunes 8 to 10 miles west of St. Anthony are plainly visible from the train. They consist of fine sand, which is drifting northeastward, and they cover several square miles. Most of the moving dunes are not more than 50 feet high, and between some of them the barren basalt bedrock is exposed. A well in the midst of these dunes is the source of drinking water for ranchers in the sand hills above.

A short distance north of St. Anthony there is a siding known as Twin Grove. To the west black basalt can be seen along Henrys Fork, and there is a broad view beyond the Sandhill Mountains, showing the uneven surface of the lavas in the distance.

|

Chester. Elevation 5,073 feet. Ogden 227 miles. |

Before reaching Chester the train passes through a small cut in basalt and the plain on the east is seen to be less smooth, owing to the thinness of the soil on the irregular surface of the underlying black lava. The low and gently sloping hills beyond are underlain by rhyolite. Far to the north is the flat-topped ridge which forms the front of the great elevated volcanic province around Yellowstone Park and which terminates the Snake River plain. Chester is the site of a grain elevator and a few houses. Where the railroad crosses Fall River1 there are exposures of basalt in the banks and bed of the stream.

1The following measurements of Fall River were made about 12 miles above the railroad bridge in 1904-1909: Maximum discharge, 4,160 cubic feet a second; minimum, 168; mean, 800. No information is available concerning power sites. Water from the river is used for irrigation, but to what extent is not known.

After crossing Fall River the railroad leaves the flat floor of the Snake River plain and heads directly for Ashton over a slightly rolling surface of basalt which is exposed in the railroad cuts. The porous, cellular, or vesicular character of this black rock can be seen from the train. The cavities were developed by expansion of gases (probably for the most part steam) contained in the molten rock and are a common characteristic of the Snake River lava.

|

Ashton. Elevation 5,256 feet. Population 502. Ogden 235 miles. |

Practically all the cultivated land hereabouts is in grain, and four grain elevators at Ashton are seen directly ahead. Ashton, which was started in 1906 when the railroad reached this point, was named for the original owner of the town site. The water supply is pumped from a deep well, and electricity is brought from a hydroelectric plant on Snake River. Ashton is an outfitting point for the fishing and hunting grounds to the north and east and for camping parties bound for Yellowstone Park.

The view of the Teton peaks from Ashton (fig. 15) is superb and doubtless has been the inducement for many a tourist and sportsman to leave the main line for the Teton Range and the Jackson Hole country in pursuit of elk, sheep, trout, and unsurpassed mountain scenery. Owen Wister's "Virginian" was glad to get out of these mountains because, as he explained, "They're most too big."

|

| FIGURE 15.—The Three Tetons, looking east. |

The average American, who has only a vague conception of the natural beauties of the Rocky Mountains and imagines that real alpine forms are found only in Switzerland, must be surprised when he first sees the lofty peaks of the Tetons. Even a man who has climbed the Matterhorn would hesitate before daring to try Grand Teton. According to local report, this peak has been ascended only twice, in 1872 and 1894. As the snow-clad mountains along the Alaskan Archipelago, rising to cloud-reaching heights, stand with their feet bathed in the ocean, so from a viewpoint near Ashton the Tetons, towering to the sky, rise from the billowy surface of a sea of golden grain. The people who live within the shadow of these mighty peaks soon look to them only as barometers of to-morrow's weather; they no longer see the grandeur that thrills the traveler, heartens the hunter, and inspires the artist.

Ashton is the junction point of the Victor branch of the Oregon Short Line, which was built to Teton Basin in 1912. On this branch 1-1/2 miles from Ashton is Marysville, a small rural settlement that can be recognized from a distance by its grain elevator. From Marysville to Jenkins all the railroad cuts appear to be in glacial material and probably a glacier heading in the Teton Mountains once extended nearly to Ashton. The canyons of Fall River and Squirrel and Bitch creeks, which the branch line crosses on high trestles, are cut in rhyolite. It was along Bitch Creek that the "Virginian" idled and fished on the day after Steve and Ed, the horse thieves, paid the penalty. Drummond, Driggs, Tetonia, and Victor are the main settlements on the branch. Victor, the terminus, is a small village 46 miles from Ashton, from which the mail stage road climbs over the Teton Range to Jackson Hole. There is a trail over the range from Driggs also. On the west side of the Teton Basin, near Victor, is the Horseshoe Creek coal district, which contains several beds of excellent bituminous coal of Cretaceous age.1

1The coal beds are irregular in thickness and extent, are displaced by numerous faults, and dip at steep angles. The Government geologist who examined the field concluded that the coal beds are thick enough to be mined profitably if they were horizontal; but the steep dip and the breaks in the continuity of the beds render mining expensive, difficult, and uncertain. The district can supply a local domestic trade for a long time, but can not be reckoned as a factor in the great coal industry of the Rocky Mountain region.

North of Ashton fields of grain slope gently to the river. Here the Snake River plain ends and the train enters a region of wooded hills. The upland against which the great plain terminates is the edge of the Yellowstone Park plateau, an elevated area of volcanic origin. In geologically recent time (Eocene and Neocene epochs) volcanoes on the east, north, and west of the park poured out enormous volumes of molten rock. Flows of rhyolitic lava filled the depressed basin between the encircling mountains and moved down the outer slopes to a considerable distance. It is the outer edge of these lava flows that the train crosses on entering the shallow rock-ribbed canyon of Henrys Fork. Here outcrops of rhyolite are seen close to the track for the first time on this line. From the entrance of this canyon to the end of the railroad the route is across lavas which are older than the basalt underlying the Snake River plain. Rhyolite is the predominant rock in Warm River canyon and on the Continental Divide, but basalt, which is interbedded with the rhyolite, and is much more resistant to weathering and erosion, underlies the mesas and caps the canyon cliffs.

In the canyon of Henrys Fork rounded outcrops of rhyolite stick their heads above the river and form the lower part of the vertical walls. Basalt makes the rim of the canyon, and its columnar jointing and cellular character may be seen from the train. The trees are Douglas fir, outliers of the Targhee National Forest, within whose boundaries the route continues to Reas Pass.

|

Warm River. Elevation 5,284 feet. Population 146.* Ogden 242 miles. |

Warm River station is at the junction of Warm River and Henrys Fork. The few settlers whose homes are along the valley bottoms cultivate the benches above the canyon rim. Warm River is so called because it has a warmer temperature than that of other waters in the region. This immediate vicinity fits the description of the country where Owen Wister's "Virginian" caught and hung the horse thieves. That job was done west of the Tetons and a day's ride from Bitch Creek.

Here the railroad leaves Henrys Fork and follows the canyon of Warm River through the wildest scenery on the entire route from Ogden to Yellowstone. The first bridge above the station crosses Robinson Creek.1

1The discharge of all three streams has been gaged near this station with the following results, expressed in second-feet (cubic feet a second):

Maximum. Minimum. Mean. Henrys Fork, 1910-1913 3,300 705 1,260 Warm River, 1912-13 900 192 295 Robinson Creek, 1912-13 1,140 53 180 There are no existing power developments on Warm River and Robinson Creek, and the water of these streams is not used to any great extent for irrigation.

Just beyond this bridge the train crosses Warm River and begins to ascend along its west bank. The grade of the track is greater than that of the stream, so the train is soon well above the dashing, tumbling, noisy brook. From this place to Mesa the angler will mentally choose his flies and long for a chance at the trout that must be hidden in those pools and rapids. Little will he care that the roadbed is a niche cut in rhyolite and that there is a small fault marked by little springs in opalescent-colored lava just below milepost 62. Immediately at the milepost the rhyolite is turned on edge, crushed, and clay streaked, but the beds at the top of the cut are horizontal, showing that there was considerable disturbance and faulting before the later lava flow. The dashing mountain stream, tumbling and jumping over bowlders, makes a more vivid appeal to the traveler than the evidences of that stream's ancient history, which is recorded in the thick beds of finely sorted sand and the thin beds of gravel exposed above and below the tracks at milepost 63. This material was deposited in ponded water after the river had cut its channel nearly to the present depth. To the question, What and where was the dam that made a pond 100 feet deep in this canyon? the geologist has not yet found an answer.

Near milepost 63 a 561-foot tunnel is to be driven to avoid the danger from the scaling off of rocks in the points around which the track now winds. A short distance beyond the trestle, at milepost 66, the train leaves the canyon and comes out on a flat surface underlain by basalt.

|

Mesa. Elevation 5,920 feet. Ogden 251 miles. |

Mesa is a siding and Y in a natural park in the forest. The principal timber seen here is Douglas fir. From Mesa the serrate crest of the Teton Range is again in view, and a mile or two away on the right is the front of a great sheet of lava, now covered with grass and trees, rising 500 feet above the flat.

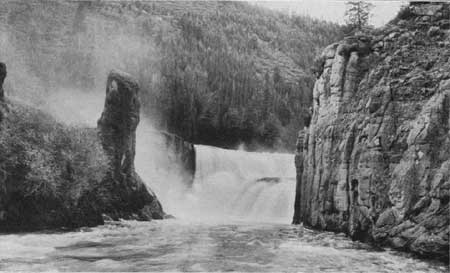

About 4 miles southwest of Mesa Henrys Fork plunges over a precipice 96 feet high with a sheer drop, and a mile below there is another fall of about 70 feet. (See Pls. XXXII and XXXIII.) The river between these two falls flows rapidly in a canyon about 250 feet deep. The land in the vicinity is now owned by a Montana electric company, which contemplates building a dam 2 miles above the upper fall and carrying the water to a power house below the lower fall, thereby getting a drop of about 450 feet with a force sufficient to develop 40,000 horsepower.

|

| PLATE XXXII.—UPPER FALLS, HENRYS FORK OF SNAKE RIVER. Photograph furnished by Oregon Short Line Railroad Co. |

|

| PLATE XXXIII.—LOWER FALLS, HENRYS FORK OF SNAKE RIVER. Photograph furnished by Oregon Short Line Railroad Co. |

About a mile north of Mesa, east of the track, there is a beaver pond, recognizable by dead trees standing in a marsh. From Mesa to Fishatch the railroad runs in a lane hewn through the forest and there is little to be seen. All the rock exposed is dark porous basalt. The low ridges through which railroad cuts have been made to depths of 6 to 10 feet—for example, that just north of milepost 70—show either arched structure or a roof-like form cracked along the top. These are called pressure ridges and seem to have been produced by an internal movement in the lava after the surface had hardened and become more or less rigid.

|

Fishatch. Elevation 6,119 feet. Ogden 257 miles. |

A State fish hatchery built in 1908 is located at the station called Fishatch, on the bank of Warm River. The main building is a log structure 40 by 80 feet, equipped with 56 hatching troughs. These troughs are supplied with water from Warm River, which passes under the railroad at this point in a concrete culvert. The hatchery breeds trout exclusively, including rainbow, eastern brook, and native trout. The hatchery has a capacity of 3,000,000 fry annually. Beef liver, ground very fine, is the principal food of trout fry. Within the State reservation of 1,280 acres there are large springs of fresh water with a temperature of 42°, which supply the spawning pond and several concrete rearing ponds. Black and brown bear and moose are hunted successfully in this vicinity.

For half a mile north of Fishatch the view from the rear of the train shows the distant snowy Teton peaks framed in a lane through the evergreen forest. On the west, at milepost 75, an old beaver dam, now grown up with willows, is seen in the ponded Warm River close to the track. Fishing for native and eastern brook trout is said to be good here.

|

Island Park. Elevation 6,290 feet. Ogden 265 miles. |

At milepost 78 the train enters the lower end of the Island Park country. Here are pits from which sand is taken by steam shovel for railroad ballast. Island Park is an open sagebrush tract several square miles in area, surrounded by a solid wall of lodgepole pine with a border of aspen. This broad flat is underlain by sand and fine gravel, composed largely of disintegrated volcanic rocks with a considerable percentage of black volcanic glass or obsidian. This mixed material is either alluvium deposited by Henrys Fork on its wide valley floor or a lake deposit. It may have been laid down in a lake caused by the ponding of the river by a glacier in the canyon below Mesa. An ice tongue or glacial dam in this canyon would have held the water back in a broad lake in which would have accumulated a deposit of sand and gravel such as is seen in the ballast pits. A low rise indicated by a slightly greater height of the tree tops about 3 miles west of Island Park is said to be an old volcanic crater. Mrs. E. H. Harriman has a large cattle ranch on the river 6 miles west.

At milepost 84 the railroad crosses Buffalo River, and a third of a mile north of the bridge there is a small cut in rhyolite, the first exposure of bedrock along the track north of Island Park. This stretch of straight track heads nearly into the gap below Henrys Lake. On the left of the gap is Sauttelle Peak, flat-topped and rising 10,123 feet above sea level, or 3,800 feet above the river. Three miles west of it is Bald Peak. The mountains east of the gap are called the Henrys Lake Mountains.

|

Trude. Elevation 6,327 feet. Ogden 270 miles. Big Springs. Elevation 6,409 feet. Ogden 275 miles. |

Trude is a siding for loading lumber and the station for Macks Place and the fishing clubs on the river. Snow lies so deep here in midwinter that the residents get about on snowshoes or skis and by dog teams. North of Trude rhyolite is seen in the rock cuts. Smoothed rock surfaces and large rounded bowlders perched on nearby knolls indicate that this country once was covered by a glacier.

At milepost 90 Henrys Fork of Snake River is seen on the west. The stream crossed at this point is formed by the discharge of Big Springs, which are half a mile east of the railroad and are reached by a wagon road that goes through a straight-cut lane in the forest to Big Spring Inn and a fishing club house. Most of the water issues at two places about 300 yards apart, and at each are several springs. The discharge of the two groups joins midway between them and at a bridge just below the junction is 120 feet wide and 3 to 4 feet deep.

A mile and a half north of Big Springs is a high wooded slope trending southeastward, the front of a great flat-topped mass of lava which came from Yellowstone Park. As the train climbs the mountain soon after leaving Big Springs, rhyolite is seen in the railroad cuts and bowlders of black glistening obsidian or volcanic glass strew the surface. These bowlders have come from ledges in the mountain side above the track. Beyond milepost 93 there is a wide view over a timbered plateau and the alluvial flat of Henrys Fork. At the upper end of this flat is Henrys Lake, which is not visible from the train. One of the railroad cuts near by yielded the material for building the station at Yellowstone.

|

Reas Pass, Idaho. Elevation 6,938 feet. Ogden 281 miles. |

At Reas Pass the train stops to test the air brakes before descending the grade to Yellowstone Park. Here the route crosses the Continental Divide, going from the Pacific slope to the valley of a small stream that flows into Madison River, thence to the Missouri, the Mississippi, and the Gulf of Mexico. Where the train enters a rock cut just beyond the railroad Y on which the helper engine turns before going back, a signboard marks the State line between Idaho and Montana. This board says that the boundary is 9 miles from Yellowstone and 6,914 feet above the sea. The rock in the cut at the divide is light-colored rhyolitic lava, but the ledges 100 feet above the track on the east are obsidian or volcanic glass. This black glass, which crumbles rather rapidly under the sudden and great changes of temperature common at this altitude, is the source of a large part of the sand that covers the broad flats below.

That glaciers once existed on the mountains around Reas Pass is shown by the ice-sculptured surface, by old glacial moraines, and by large bowlders which have evidently been transported by ice. Such bowlders may be seen as the train descends the north side of the mountain. The timber at Reas Pass is mostly a dense growth of young lodgepole pine, through which it is difficult to travel except by the opened roads and trails, because of the intricate network of fallen poles killed by fire.

The train runs slowly down the steep grade north of the pass as it follows a small, rapid brook which to a fisherman's eye looks like good trout water. Light-colored rhyolite is exposed in the railroad cuts. Down a little valley the train goes, and the view reaches no farther than the wooded flat-topped mountains near by. In fact, there is practically nothing to see but trees from this point to Yellowstone station. At milepost 105 the foot of the grade is reached, and from this point to Yellowstone the road bed is on the flat pine-covered surface of a wide alluvial deposit, made by Madison River when it flowed over this part of its flood plain.

The sand carried by the river and spread on its flood plain is derived from the crumbling of volcanic rocks and owes its dark color to a considerable percentage of black volcanic glass. The forest here is practically all young lodgepole pine, sometimes called jack pine.

|

Yellowstone, Mont. Elevation 6,669 feet. Ogden 291 miles. |

As the traveler alights at Yellowstone, the terminus of the railroad, his eye will turn from the attractive station, built of pink rhyolite, to the four-horse stage coaches waiting for passengers. He may not notice that the engine is within a few rods of a line of blazed trees at the end of the station grounds, but those blazed trees are significant. They mark the boundary of Yellowstone National Park.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

bul/612/sec23.htm

Last Updated: 28-Mar-2006