|

Geological Survey Bulletin 612

Guidebook of the Western United States: Part B |

ITINERARY

|

|

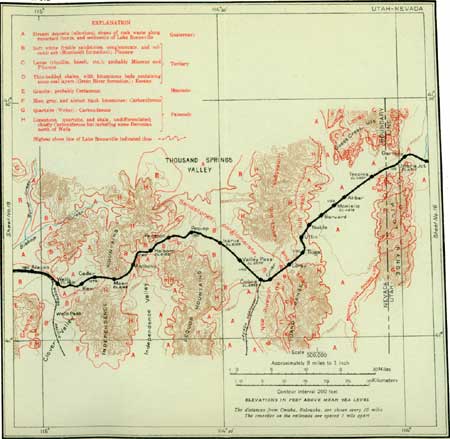

SHEET No. 17. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

The actual junction of the present line with the original route of the Central Pacific around the north end of Great Salt Lake is at Umbria Junction (see sheet 17, p. 162), half a mile beyond Lucin station. Once a week a train is sent over the old route.

Between Umbria Junction and Tecoma light-colored clay and gravels in regularly bedded deposits are exposed along the railroad. These are either deposits in the waters of Lake Bonneville or later stream deposits of wash brought down by erosion from lake-bed clays and beach materials higher up. These beds show a slight tilt toward the east, indicating that they were probably left here by running water.

The Utah-Nevada State line, marked by a monument and a fancifully decorative design in set stones at the north side of the track, is passed opposite the first ranch building seen west of Great Salt Lake. To the south the State line passes over the escarpment capped by lava (basalt), the columnar jointing (see footnote on p. 121) of which may be distinguished even at this distance.

|

Nevada. |

Nevada is a Spanish word meaning "snowy" or "white as snow," and the name of the State was derived from the Sierra Nevada. The State ranks sixth in size in the Union. Its length from north to south is 484 miles, its width 321 miles, and its area 109,821 square miles, of which about 60 per cent has been covered by public-land surveys and approximately 21 per cent has been appropriated. National forests in Nevada cover an area of 8,683 square miles, and Anaho Island, in Pyramid Lake, has been made a bird reservation. The population of Nevada, according to the latest census, was 81,875, or about one person for each 1.4 square miles.

Nevada is one of the most important metal-mining States of the West and has yielded large quantities of gold, silver, and lead. Of late also it has become a large producer of copper.

The history of Nevada is chiefly the history of its mines. Since the discovery of the Comstock lode and other famous ore bodies, periods of activity and prosperity have alternated with periods of depression. Each discovery of high-grade ore in noteworthy quantity has been followed by rapid settlement in that locality and the establishment of one or more towns. Exhaustion of the richer or more accessible ores or the bursting of overinflated speculative bubbles has been followed by at least local stagnation and depopulation. In 1890-1893 a sharp decline in the price of silver initiated or accompanied a period of depression in Nevada's mining and general industrial prosperity. Silver is so important a resource of the State that to a large extent even now its prosperity depends upon the market for that metal. Of late years, however, an increased production of gold, copper, and recently of platinum has accompanied a gradual and, it is hoped, substantial industrial progress. Permanent towns have grown up and agriculture and related pursuits are becoming firmly established.

The mining districts in the State number about 200 and are widely distributed over its area. Almost every one of the larger mountain ranges contains some ore. In the following pages emphasis will be laid on the record and the development of mining districts adjacent or tributary to the railroad. More complete accounts of most of the districts may be found in the publications of the United States Geological Survey.

The geology of Nevada is that typical of the Great Basin, in which the two prevalent topographic elements are the basin ranges and the intervening valley plains. In the mountains probably the most conspicuous rocks are the Tertiary lavas, although a full series of sedimentary beds is also present, as well as great masses of intrusive igneous rocks of various types. The rocks may be briefly mentioned in the order of age. (See table on p. 2.) The pre-Cambrian basal or foundation rocks, on which the younger sedimentary rocks and lavas rest, are visible in a few places. East of a line passing somewhat east of Winnemucca through Austin to a point a little west of Tonopah Paleozoic strata are the predominating sedimentary rocks in the mountain ranges, which include few or no Mesozoic beds. The enormous thickness of the Paleozoic section at Eureka (almost 30,000 feet) suggests that the shore line of the Paleozoic sea was somewhere near this place. This is further indicated by the fact that west of the line mentioned the Paleozoic rocks disappear and are succeeded by a thick series of Triassic and Jurassic sediments. During the Paleozoic era western Nevada was apparently a land from which sediments were washed into a sea on the east. In Mesozoic time the situation seems to have been reversed. The Jurassic and Triassic sediments were apparently derived from a land area of uplifted Paleozoic strata in the eastern part of the State. The Triassic limestone, slate, and sandstone and the associated lavas of the Humboldt Range have an estimated thickness of 10,000 feet. Somewhat similar Jurassic rocks add several thousand feet more to the record of deposition in this region during Mesozoic time. No Cretaceous sediments have been found in Nevada, and it is therefore supposed that the Great Basin during that period was a land area.

Large and small bodies of granular intrusive igneous rocks, chiefly such as may be called granite (including quartz monzonite, granodiorite, and similar rocks), extend from the great masses in the Sierra Nevada to the eastern part of the State or beyond. All these bodies may be more or less related; they appear to be younger than most of the Jurassic sediments but older than the Tertiary rocks and are probably of Cretaceous age. The Tertiary lavas (rhyolite, andesite, and basalt) are widely distributed and cover large areas, some ranges being entirely made up of them. Vast areas in the valleys are covered with the gravelly deposits of streams, with material laid down in lakes, or with the ash or pumice ejected with the lava during volcanic eruptions.

The movements by which the mountains and valleys have been formed probably occurred in different periods, but it is evident that most of them broke and shifted the sheets of Tertiary lava, and were therefore subsequent to these lava flows in date. The present ranges in the Great Basin are therefore young compared with mountains in general. They are supposed to have been uplifted by movements that lasted at least through a part of Tertiary time and perhaps have extended to the present day. The earth breaks or faults along which the mountain blocks were upheaved are still recognizable at many places in the topographic form of the mountains.

|

Tecoma, Nev. Elevation 4,807 feet. Omaha 1,114 miles. |

As a supply or trading point Lucin is now largely superseded by Tecoma, a considerable settlement a few miles farther west. Of the mines in the Lucin district,1 south of Tecoma, only the Copper Mountain mine has lately shipped much ore. This mine is connected with the railroad by a 6-mile spur track and an aerial (wire cable) tramway. Stock raising is now the principal industry in this region, but north of the railroad there are some large land holdings which are to be subdivided and utilized under a private irrigation project.

1The Lucin mining district is in the Ombe or Pilot Range, a few miles south of Tecoma. Ore was discovered in the district about 1869, and there was a considerable output of silver and lead until about 1876, after which the district was nearly deserted. The increasing demand for copper in recent years has encouraged the development of the copper deposits in the Lucin district, and the value of the copper produced there from 1906 to 1912, inclusive, was approximately $1,700,000.

The sedimentary rocks of the district are chiefly of Carboniferous age. They have been invaded by igneous rocks of various kinds, the larger bodies of which consist of a coarsely porphyritic rock of granitic character (quartz monzonite porphyry). The black rocks seen from the railroad at the north end of the range are basaltic lavas.

The ore bodies, which embrace copper deposits and lead-silver deposits, have resulted from the replacement of limestone adjacent to faults and fissures. The copper ores are oxidized, no sulphides having yet been reached. The lead-silver ores are also oxidized. Wulfenite, the yellow molybdate of lead, is abundant, and the district is probably best known to mineralogists for the beautiful crystalline specimens of this mineral that it has yielded.

After ascending the drainage channel above Lucin, the railroad passes out into a broader and more open valley through which the track heads straightaway toward Montello. In this valley the railroad reaches the elevation of the uppermost water level of the former Lake Bonneville, but traces of the old lake shores are not readily discerned.

|

Montello. Elevation 4,878 feet. Population 355.* Omaha 1,120 miles. |

Montello is a railroad town and the first freight terminal west of Ogden. The characteristic Nevada or Great Basin scenery is well displayed here, steep mountain ranges with rugged declivities contrasting sharply with the broad, gentle slopes of rock waste and gravel from which they project. The railroad winds in and out among such ranges all the way across Nevada, generally finding low passes through them or going around the end of the ranges.

Leaving Montello the road begins the steeper climb by which it passes over the divide and out of the Bonneville Basin. The highest water level of old Lake Bonneville lay somewhere near Montello, at an elevation of about 5,000 feet, probably just above the town, but no distinct traces of the old water line can be seen from the train. Looking back or down across the valley (southward), the traveler may see Pilot Peak, the highest point at the south end of the Pilot Range. Banvard (elevation, 4,976 feet), Noble (5,117 feet), Ullin (5,256 feet), Tioga (5,597 feet), and Omar (5,640 feet), passed in the order named, are mere sidetracks or minor stations.

The surface material of the valley is mostly a light-colored clay mingled with pebbles and fragments of rock. The fragments include many of light-gray limestone, evidently representing rock that is exposed in the adjacent mountains. The valley is covered with a fairly uniform growth of brush, and the sparse grass which in less arid regions would hardly be noticed affords good grazing for stock. The mountains appear smooth and rounded as seen from a distance and are in part covered with a scanty growth of cedars.

Just beyond Tioga, a sidetrack and signboard near milepost 653, the railroad reaches the head of the open valley. Bedrock projects in many places, and ridges of rock extend down from the mountain front to the north toward the railroad. These are limestones and quartzites of Carboniferous age. Similar rocks show as rugged edges on the more distant mountains to the south. In the reports of the Fortieth Parallel Survey the pass through which the railroad climbs was named Toano Pass, and the mountains to the south were called the Gosiute Range and those to the north the Toano Mountains. A large part of the high country for a long distance beyond Toano Pass is made up of Carboniferous sediments. Phosphate rock is reported to have been found in these rocks in the same relative position as in the great phosphate fields of southern Idaho and vicinity, but in Nevada the beds, so far as known, are too thin to be of commercial value.

From the upper end of Toano Pass, near milepost 649, may be seen in the valleys on both sides beds that are conspicuously exposed as chalky-white cliffs or as bare white patches on the rolling plains or on low ridges. These beds are composed mainly of friable gray, white, and drab sandstone and marly limestone, at many places containing a great deal of volcanic material, chiefly the tuff or ash that accompanied lava (rhyolitic) eruptions. These rocks belong to the Humboldt formation1 and cover large areas in this part of Nevada.

1The Humboldt formation was described by Clarence King in 1878 as the deposit of a great lake which he thought had occupied most of the territory from the Wasatch Mountains in Utah to the Sierra Nevada, in Pliocene time. He named this hypothetical body of water Shoshone Lake, and these sediments, which he supposed had been laid down in its water, he called the "Humboldt series." During recent years little attention has been given to the further study of this formation, but geologists of the present day are much inclined to doubt the existence of the extensive lake thus conjectured, as well as the necessity for assuming that these beds as a whole were lake deposits.

|

Cobre. Elevation 5,922 feet. Omaha 1,138 miles. |

At Cobre (pronounced co'bray, Spanish for copper) is the junction with the Nevada Northern Railroad, which since 1906 has given access to the Ely or Robinson copper districts,1 140 miles to the south, and a number of other less well-known districts, including Cherry Creek and Egan Canyon.2

1The first mining locations in the vicinity of Ely were made in 1867, three years after the organization of the Eureka mining district, in the same year in which bonanza silver ores were discovered in the White Pine district, 60 miles to the west. Early operations disclosed a few deposits of lead-bearing ores carrying precious metals to the value of $10 to $40 a ton. Occasionally small bonanzas were found, and shallow deposits of rich copper ore were mined.

The present copper industry of the district is the outgrowth of explorations that began about 1901. The aggregate quantity of low-grade sulphide ore developed is perhaps 80 million tons, in which the mean copper content is a little over 1-1/2 per cent. In 1906 extensive reduction works were built at McGill, on the east side of Steptoe Valley, about 25 miles from the mines.

The sedimentary rocks of the district, comprising limestones, quartzites, and shales, range in age from Ordovician to Pennsylvanian. They have been disturbed by folding and especially by faulting and have been invaded by masses of igneous rocks (monzonite porphyry).

The ore, like the greater part of that at Bingham, Utah, consists of monzonite porphyry, greatly altered (metamorphosed) as a result of the igneous intrusions, carrying disseminated grains of pyrite and chalcopyrite, and varying amounts of chalcocite. Masses of porphyry which, through metamorphism, had been almost uniformly charged with grains of pyrite and chalcopyrite became subject to erosion and oxidation. As the rock was gradually worn down, surface waters attacking the metallic sulphides and charged with copper derived from them soaked downward into the rock and deposited the dissolved copper by chemical reaction with the pyrite and chalcopyrite in the rock. In this way a part of the rock was gradually converted into ore by addition of the copper sulphide. Superficial examination of ore samples shows a white to gray rock specked through and through with a black mineral, which is the rich copper sulphide chalcocite. On close inspection it is found that this mineral occurs mainly as films or coatings on grains of the pale-yellow iron mineral pyrite or the deeper yellow copper-iron sulphide chalcopyrite. The oxidized capping or overburden has an average thickness of about 100 feet. The underlying ore blankets are from 15 to 500 feet thick. Up to the present time comparatively little underground mining has been done, though caving methods were employed in the Veteran mine. The Ruth ore body, estimated to contain 5 to 10 million tons of ore carrying over 40 pounds of copper to the ton, may be mined in a similar way. Where the overburden is shallow the ore is mined by steam shovels, and between 1908 and January, 1914, nearly 12 million tons of ore averaging about 38 pounds of copper to the ton had been produced in this way, and in addition some 20 million tons of overburden had been removed.

2On the west side of Steptoe Valley, 93 miles south of Cobre, are the Cherry Creek and Egan Canyon mines, in a low pass that was used by the Pony Express and Overland Stage in pioneer days. Gold was discovered here in 1861, and between 1872 and 1882 the district supported a population of about 3,000. The total production amounted to several million dollars, but at present comparatively little work is in progress. Gold ores and silver-lead ores occur here in sedimentary rocks, principally in quartzite.

In the Gosiute mining district, which lies 20 miles south of Cherry Creek, in the Egan Range, silver-lead ores have recently been mined from veins occurring in limestone. The Spruce Mountain, Hunter, Schellbourne, Duck Creek, and Ward mining districts, in which work has been more or less active during recent years, are also tributary to the Nevada Northern Railroad.

West of Cobre the railroad crosses a number of scarcely perceptible divides. The old town of Toano, opposite milepost 643, is now represented only by a few fallen and deserted stone buildings. These were built from blocks cut from the sandstone of the Humboldt formation (Pliocene) near by. Valley Pass (elevation 6,072 feet) is the highest of the low divides just mentioned. It is marked by a railroad station and a water tank. The mountains across the rolling valley to the north, grassy on top but more or less thickly covered with scrubby cedar trees on their lower slopes, are composed of Paleozoic sandstone, shale, and limestone.

Beyond Valley Pass the drainage channels lead off to the northwest toward Thousand Springs Valley. The broad brush-covered plains adjacent to the railroad have little distinctive character geologically or otherwise. They are presumably underlain by the volcanic ash beds (tuffs) and other beds of the Humboldt formation, which are trenched by shallow gullies. Cuts along the railroad show stream-deposited gravels.

Within the 30 miles west of milepost 637 the train passes Icarus (elevation 6,108 feet), Pequop (6,143 feet), Fenelon (6,153 feet), Holborn (6,103 feet), Anthony (6,124 feet), Moor (6,166 feet), Cedar (5,969 feet), and Kaw (5,831 feet)—merely sidetracks, section houses, or water tanks maintained chiefly for the use of the railroad. For a long distance the coarse white tuffaceous sandstones of the Humboldt formation are the principal rocks seen near the railroad. Just beyond Pequop, however, between mileposts 630 and 629, are conglomeratic strata interlayered with evenly bedded clays or clay shales of a distinct light-greenish color, which are believed to be of older Tertiary age (Eocene, Green River formation). Faults displacing the clays and conglomerate are visible in the railroad cuts but possibly would not ordinarily be noticed from the train.

Between Anthony and Moor an extensive view may be had to the south and southeast over the north end of Independence Valley, the larger part of which lies beyond the range of vision. This valley constitutes another of the distinct drainage units of which the Great Basin is composed. The railroad continues to ascend gradually, skirting the slopes at the north edge of the valley. For several miles near the summit of this part of the route the road passes through groves of cedars, such as are frequently observed from a distance on the flanks of desert mountain ranges.

|

Moor. Elevation 6,166 feet. Omaha 1,166 miles. |

At Moor the divide between the drainage of Independence Valley and that of Humboldt River is reached, and the traveler enters the area tributary to the ancient Lake Lahontan, an extensive body of water that formerly spread out through most of the lower valleys in northwestern Nevada. (See p. 172.)

From the summit of Moor the train makes a long westward descent, at first down a heavy grade between Moor and Wells. Minor stations along the way are Cedar and Kaw. A broad valley extends off toward the north, the railroad skirting its southern side. Tulasco Peak, the prominent pointed summit in the range across this valley, is formed of limestone and quartzite of Carboniferous age, with lava (rhyolite) at its base and beds of Pliocene tuff in the valley.

|

Wells. Elevation 5,631 feet. Population 598.* Omaha 1,175 miles. |

Wells, formerly a more important settlement and trading center than it is now, was named from a group of springs called Humboldt Wells, an objective point along the branch of the old overland emigrant trail, which here comes from the south into the route followed by the Southern Pacific. From Great Salt Lake to Wells the trail followed in general the route which has been taken by the Western Pacific Railway. From Wells to a point a little beyond Winnemucca both the Southern Pacific and the Western Pacific run in nearly parallel lines down the valley of Humboldt River, beyond which they diverge to separate passes across the Sierra Nevada.

The springs at Wells are reported to be from 30 to 150 in number and range in size from a few inches to 3 or 4 rods across. They are inconspicuous little pools scattered about in a grassy meadow just north of the railroad, a short distance west of the town. The flow is variable; it reaches a maximum about October, but during a large part of the year there is no overflow at all. This variability with the season indicates that the springs may originate in the underflow drainage in the valley, rather than from some deeper-seated source, which probably would not be so subject to seasonal influences. These wells have been called the head of Humboldt River, but that stream has longer branches, which enter the valley below Wells.

Wells is still the center of an extensive cattle and sheep industry, which has now largely replaced the mining of earlier days. A large private irrigation project is being carried out in the valley beyond the high mountains to the north. Near Wells, Humboldt River, Willow Creek, Trout Creek, and Meadow Creek supply water for the irrigation of 1,900 acres, or about 3 square miles of land, which is devoted principally to growing winter feed for stock, although, according to reports, barley, oats, potatoes, and cabbage are also raised. Clover Valley, at the foot of the Ruby or East Humboldt Range, south of Wells, is a good agricultural and stock-raising valley that was formerly dependent for its transportation facilities on Wells but is now served by the Western Pacific Railway.

Humboldt River, which was so named by Frémont, and which is one of the largest river systems in Nevada, heads entirely within the desert ranges of the central Great Basin. It rises on the eastern border of Nevada and flows westward for about 200 miles. Near some of the higher mountains it receives considerable water, but it dwindles downstream and finally disappears. It enters the basin formerly flooded by the waters of Lake Lahontan near the present town of Golconda and from that point continues its course through Lake Lahontan beds for nearly 100 miles to Humboldt Lake. In the dry season the river water gets no farther than Humboldt Lake, but during the winter this lake commonly overflows, the waters passing on to the Carson Sink, where they are evaporated. Throughout its course it is almost if not quite destitute of native trees along its channel. In its upper course Humboldt River receives a number of tributaries, the largest of these being Reese River, which enters it from the south. During the summer and fall several of these streams, including Reese River, commonly dry up before they reach the main channel.

Just below Wells the train runs along the margin of a strip of meadowland and then passes into a narrower portion of the valley hemmed in by low bluffs on each side. These bluffs and the cuts along the railroad show bedded deposits of white and greenish clays or sand, which are classed with the Tertiary Humboldt formation. Beyond the narrows lies a broader valley.

As the valley opens out the traveler may see to the south a panorama of the Ruby or East Humboldt Range, the highest and most rugged mountain mass in Nevada. The name Ruby Mountains, or Ruby Range, is locally accepted in preference to East Humboldt and seems to have priority. Old settlers describe the finding of "rubies" and "ruby sand" in the gravels of some of the streams coming from these mountains. Specimens of these "rubies" are in fact red garnet, a rather common mineral developed in rock under the influence of the heat accompanying igneous intrusion.

At first only the north end of the range, around which the railroad passes, is seen, but farther west the western flank and the lofty summits come into view. A number of these peaks attain a height of 11,000 or 12,000 feet, and snow lingers along the crest of the range late into the spring and comes early in the fall. Owing to their height these rugged slopes receive a larger rainfall than the surrounding country and supply water to the adjacent valleys, which contain some of the most productive agricultural regions in the State. On the east slope of the Ruby Range the waters quickly disappear in the beds of the narrow canyons but break out again lower down in cold springs that feed Ruby and Franklin lakes. On the west side the descent is more gentle and the waters gather in the South Fork of the Humboldt. The crest of the Ruby Range is included in the Humboldt National Forest.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

bul/612/sec26.htm

Last Updated: 28-Mar-2006