|

Geological Survey Bulletin 614

Guidebook of the Western United States: Part D. The Shasta Route and Coast Line |

ITINERARY

|

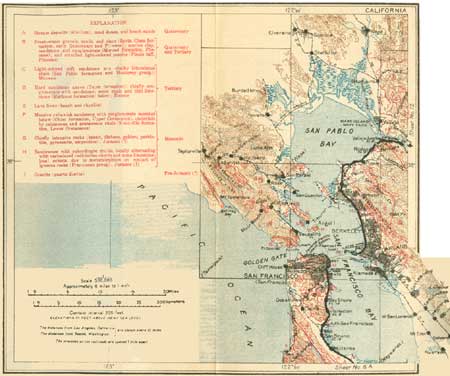

| SHEET No. 13 (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

|

Port Costa. Elevation 11 feet. Seattle 926 miles. |

Port Costa (see sheet 13, p. 90), the western ferry terminus, is a shipping point, particularly for grain, which comes from the interior valley1 and is here loaded into ocean-going vessels. A long line of galvanized-iron grain warehouses may be seen on the water front.

1Agriculture in California had its beginning in wheat raising, and wheat was long the State's greatest crop. Its production steadily increased, until about 1884, to over 54,000,000 bushels annually. The levelness of the great grain fields of the valley led to the utilization of combined harvesters, steam gang plows, and other farm machinery of extraordinary size and efficiency. Recently, however, fruit growing has become a more important industry than grain farming. In the value of its fruit crop California leads all the other States.

On leaving Port Costa the train skirts the south shore of Carquinez Strait, where the steep bluffs offer many good exposures of folded sedimentary rocks. The first rocks seen are Upper Cretaceous (Chico) sandstone and shale. The rocks have a moderately steep westward dip and trend almost directly across the course of the railroad, so that as the train proceeds successively younger formations are crossed. At Eckley, a short distance beyond Port Costa, brick is manufactured from the Cretaceous shale. At Crocket is a large sugar refinery. Mare Island, across Carquinez Strait, is the site of the United States navy yard, which, however, is not readily discerned from this point. The Cretaceous shales and sandstones continue to Vallejo Junction and a little beyond.

On the southeast side of San Pablo Bay, near the west end of Carquinez Strait, there are wave-cut terraces and elevated deposits of marine shells of species that are still living. These terraces and deposits do not show south of San Pablo Bay, and therefore seem to indicate the recent elevation of a block including only a portion of the shore around the bay. This block probably includes the Berkeley Hills and a considerable territory to the east, perhaps even extending to Suisun Bay.

|

Vallejo Junction. Elevation 12 feet. Seattle 929 miles. |

From Vallejo Junction a ferry plies to Vallejo (val-yay'ho), which is on the mainland opposite the navy yard and from which railroad lines extend into the rich Napa and Sonoma valleys. Santa Rosa, the home of the famous Luther Burbank, is in the Sonoma Valley. Vallejo was named from Gen. Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo, who played a prominent part in the early history of California. It was the capital of the State from 1851 to 1853. Beyond Vallejo Junction Carquinez Strait begins to open out into San Pablo Bay.1 (See Pl. XXIV, B, p. 78.)

1The section along the shore of San Pablo Bay between Vallejo Junction and Pinole (see map and section on stub of sheet 13, p. 90) includes six of the most widespread divisions of the sedimentary series in the Coast Range region of California. The formations or groups represented are the Chico (Upper Cretaceous), Martinez (Eocene), Monterey (earlier Miocene), San Pablo (later Miocene), Pinole tuff (Pliocene), and Pleistocene. The only large divisions of the middle Coast Range sequence not represented are the Franciscan (Jurassic?), Tejon (Eocene), and Oligocene, all of which are found within a few miles to the east and south.

In the San Pablo Bay section all the formations below the Pleistocene are included in a syncline, on the northeast side of which the strata are nearly vertical, but on the southeast side the dip of the beds is lower. The Pleistocene beds rest horizontally across the truncated edges of the Miocene and Pliocene. The aggregate thickness of the sediments in the San Pablo Bay section is not lees than 8,000 feet. With the exception of the Pliocene and a portion of the Pleistocene, all the formations are of marine origin. A portion of the Pinole tuff was certainly deposited in fresh water. The Pleistocene beds were deposited under varying marine, estuarine, and fluvial conditions.

Fossil remains are found in all the formations of the San Pablo Bay section, and at least six distinct faunas are represented. Very few specimens have been procured in the Chico near the line of the railroad, but abundant fossils are found in the same formation a few miles to the east. The Martinez fauna is represented in the cliff opposite the Selby smelter. The Monterey and the San Pablo contain abundant remains. The fresh-water fauna of the Pinole tuff is represented by molluscan species. Leaves and remains of vertebrates are also present. The Pleistocene shale contains abundant marine shells of a few species, with mammal bones representing the elephant, horse, camel, bison, ground sloth, antelope, lion, wolf, and other forms.

The dark Cretaceous shales near the railroad station at Vallejo Junction are soon succeeded by brown shales and massive sandstones belonging higher in the Cretaceous system. The contact between the Chico and the Martinez (Eocene) beds is in a fault zone cut by the railroad tunnel a short distance west of Vallejo Junction. Just beyond the tunnel the contact between the Martinez and the Monterey (Miocene) is clearly shown in a high cliff to the left, opposite the Selby Smelting Works, where the buff-colored Monterey sandstones and shales rest with marked unconformity upon the black Eocene shales. Near the contact the Eocene shale is filled with innumerable fossil shells of boring Miocene mollusks. The Monterey beds are extraordinarily well exposed in the cliffs to the left, and immediately beyond the contact, where they consist of fine buff shales with shaly sandstones and thin bands of yellow limestone.

After leaving these cliff exposures the train passes Tormey station, crosses a little swamp, and approaches a tunnel cut into vertical cliffs of massive gray sandstone; this is the type locality of the San Pablo formation (upper Miocene). The refining plant of the Union Oil Co., at the east end of this tunnel, is located on the upper part of the San Pablo beds. Vertical beds of massive tuff immediately west of the oil refinery represent the lower part of the Pinole tuff. Beyond these beds the train crosses another swamp and enters a cut in which white volcanic ash beds of the Pinole tuff dip at a relatively low angle to the northeast. This change in dip shows that these beds are on the southwest side of the San Pablo Bay syncline, the axis of which passes through the swamp area. Resting upon the tilted ash deposits in this part of the section are horizontal beds of Pleistocene shale.

|

Rodeo. Elevation 12 feet. Seattle 932 miles. |

The name Rodeo (ro-day'o), meaning "round-up," indicates that the station so called was formerly a cattle-shipping point. Beyond Rodeo the train enters a series of cuts. Near the station are exposures of massive tuffs close to the base of the Pinole tuff. Beyond this point the San Pablo (Miocene) appears, with low dips to the northeast. In the sea cliffs on San Pablo Bay a few yards from the railroad are excellent exposures of the Miocene capped by Pleistocene shale. At Hercules, where there are large powder works, the railroad cut is in broken shale of the Monterey group, the same beds that were seen near the Selby smelter, on the northeast side of the syncline. Beyond Hercules the railroad passes over Monterey shale to the town of Pinole (pee-no'lay, a Spanish term used by the Indians for parched grain or seeds), where the Pinole tuff is in contact with the Monterey and is covered by a thick mantle of the Pleistocene shale. In the cuts southwest of Pinole the rocks exposed are all either steeply inclined Pliocene tuffs or horizontal Pleistocene beds.

|

Pinole. Population 798. Seattle 935 miles. |

At Krieger, where the tracks of the Santa Fe Route may be seen approaching the bay front from the south, is a so-called "tank farm." The oil-storage tanks, which belong to the Standard Oil Co., are beyond the Santa Fe line. Beyond Sobrante station is Giant, another powder factory, and beyond that are pottery works which obtain clay from Ione, in the Sierra Nevada. The bay shore near Oakland is largely given over to industrial uses, on account of its facilities for rail and water transportation.

|

San Pablo. Elevation 30 feet. Seattle 940 miles. |

Beyond Giant the foothills retreat from the bay shore and the rail road enters the broad lowland on which the cities of Berkeley and Oakland are built. Near San Pablo, in the vicinity of San Pablo and Wildcat creeks, there is a gravel-filled basin. Many wells sunk in this gravel may be seen near the tracks, and from them a municipal water company and both railroads obtain water. West and south west of San Pablo station a line of hills shuts out a view of San Francisco Bay. These hills constitute the Potrero San Pablo, so called because, being separated from the mainland by marshes, they were a convenient place in which to pasture horses during the days of Mexican rule, when fences were practically unknown. The hills are made up wholly of sandstone. belonging to the Franciscan group.1 On the other side of them are wharves, warehouses, and large railway shops belonging to the Santa Fe system. From that side, also, the Santa Fe ferry plies to San Francisco.

1The rocks of the Franciscan group comprise sandstones, conglomerates, shale, and local masses of varicolored thin-bedded flinty rocks. The flinty rocks consist largely of the siliceous skeletons of minute marine animals, low in the scale of life, known as Radiolaria, and on this account they are known to geologists as radiolarian cherts. All the rocks mentioned have been intruded here and there by dark igneous rocks (diabase peridotite, etc.), which generally contain a good deal of magnesia and iron but little silica. The peridotites and related igneous rocks have in large part undergone a chemical and mineralogic change into the rock known as serpentine. Closely associated with the serpentine as a rule are masses of crystalline laminated rock that consist largely of the beautiful blue mineral glaucophane and for that reason are called glaucophane schist. Schist of this character is known in comparatively few parts of the world but is very characteristic of the Franciscan group. It has been formed from other rocks through the chemical action known as contact metamorphism, set up by adjacent freshly intruded igneous rocks. The Franciscan group is one of the most widespread and interesting assemblages of rocks in the Coast ranges.

|

Richmond. Population 6,802. Seattle 942 miles. |

Richmond, on both the Southern Pacific and the Santa Fe lines, is becoming a busy shipping, railroad, and manufacturing point, on account of the congestion of the water front of Oakland and San Francisco. The hills on the east side of the track, known to old Californians as the Contra Costa Hills but now often referred to as the Berkeley Hills, rise steeply from the plain. The most conspicuous summit from the west is Grizzly Peak (1,759 feet), but Bald Peak, just east of it, is 171 feet higher. The hills are generally treeless on their exposed western slopes, although their ravines and the eastern slopes are wooded.1

1The geologic structure of these hills is rather complicated. Along their southwest base, between Berkeley and Oakland, is a belt of the sandstones, cherts, and schists belonging to the Franciscan (Jurassic?) group and characteristically associated with masses of serpentine. Overlying the Franciscan rocks are sandstones, shales, and conglomerates of Cretaceous, Eocene, and Miocene age. These in turn are overlain by tuffs, freshwater beds, and lavas of Pliocene and early Quaternary age. The general structure of the ridge east of Berkeley is synclinal, the beds on both sides dipping into the hills. The upper part of Grizzly Peak is formed chiefly of lava flows of Pliocene age.

Beyond San Pablo and Richmond the rocks of the Franciscan group outcrop in low hills. At Stege the railroad is still close to the shore of the bay. Between this place and the hills is one of the suburbs of Berkeley known as Thousand Oaks. The traveler can get here an unobstructed view out over the bay and through the Golden Gate. Mount Tamalpais is on the right and San Francisco on the left. Just to the left of the Golden Gate the white buildings of the Exposition grounds can readily be distinguished if the day is at all clear. At Nobel station a little wooded hill of Franciscan rocks stands close to the railroad on the left. Beyond Nobel an excellent view may be had of the hilly portion of the city of Berkeley.

|

Berkeley. Elevation 8 feet. Population 40,434. Seattle 948 miles. |

West Berkeley station, also known as University Avenue, is in the older part of the city of Berkeley, and the center of the city is now almost 2-1/2 miles back toward the hills. Berkeley was named after Bishop Berkeley, the English prelate of the eighteenth century who wrote the stanza beginning "Westward the course of empire takes its way," by those who chose it as a site for the University of California. One of them, looking out over the bay and the Golden Gate, quoted the familiar line, and another suggested "Why not name it Berkeley?" and Berkeley it became.

The University of California was founded in 1868. It is one of the largest State universities in America, including besides the regular collegiate and postgraduate departments at Berkeley the Lick Observatory, on Mount Hamilton; colleges of law, art, dentistry, pharmacy, etc., in San Francisco; the Scripps Institution for Biological Research, at La Jolla, near San Diego; and other laboratories for special studies elsewhere. It is a coeducational institution and had a total enrollment for 1914-15, not including that of the summer school, of 6,202. The members of the faculty and other officers of administration and instruction number 890. The university buildings at Berkeley are beautifully situated and have a broad outlook over San Francisco Bay. Their position can readily be identified from the train by the tall clock tower. Another prominent group of buildings occupying a similar site just south of the university grounds is that of the California School for the Deaf and the Blind.

Just before reaching Oakland (Sixteenth Street station) the train passes Shell Mound Park. The mound, which is about 250 feet long and 27 feet high, is on the shore of the bay close to the right side of the track. It is composed of loose soil mixed with an immense number of shells of clams, oysters, abalones, and other shellfish gathered for food by the prehistoric inhabitants of the region and eaten on this spot. The discarded shells, gradually accumulating, built up the mound. Such relics of a prehistoric people are numerous about the bay, for over 400 shell mounds have been discovered within 30 miles of San Francisco. The mound just described is one of the largest, and from excavations in it a great number of crude stone, shell, and bone implements and ornaments have been obtained. The mounds evidently mark the sites of camps or villages that were inhabited during long periods, for the accumulation of such refuse could not have been very rapid. Archeologists who have studied the mound say that it must have been the site of an Indian village over a thousand years ago, and that it was probably inhabited almost continuously to about the time when the Spaniards first entered California.

|

Oakland. Elevation 12 feet. Population 150,174. Seattle 951 miles. |

The first stop in the city of Oakland is made at the Sixteenth Street station, about 1-1/2 miles from the business center of the city. Oakland is the seat of Alameda County and lies on the eastern shore of San Francisco Bay directly opposite San Francisco. Its name is derived from the live oaks which originally covered the site. It is an important manufacturing center and has a fine harbor with 15 miles of water front. Visitors to Oakland should if possible take the electric cars to Piedmont, from which a fine view may be had of San Francisco, the bay, and the Golden Gate. This view is especially good sunset. A walk or drive to Redwood Peak takes the visitor past the former home of Joaquin Miller, author of "Songs of the Sierras" and many other familiar poems, and affords equally fine views.

Leaving the station at Sixteenth Street, the train skirts the west side of the city and runs out on a pier or mole 1-1/3 miles long, from which the rest of the journey must be made on the San Francisco ferries. The distance across the bay is 4 miles, and the trip is made in about 20 minutes. In crossing the bay the traveler sees Goat (or Yerba Buena), Alcatraz, and Angel islands to the right, Marin Peninsula beyond them, and the Golden Gate opening to the west of Alcatraz.

Goat Island lies close to the ferry course across the bay. Like most of the other islands in the bay, it is owned by the Government. On the nearest point there is a lighthouse station, and below it the rocky cliff is painted white to the water's edge. Just to the right of this is the supply station for the lighthouses of the whole coast from Seattle to San Diego. Behind this station is the United States naval training station, of which the officers' quarters may be seen on the hillside and the men's quarters near the larger buildings below. At the extreme northeast point of the island is a torpedo station, where torpedoes are stored for use in the coast defense.

On Alcatraz, the small island west of Goat Island, is a United States disciplinary barracks, and on Angel Island, north of Alcatraz, are barracks and other military buildings, a quarantine station, and an immigrant station.

Few people in viewing the Bay of San Francisco think of it in any other way than as a superb harbor or as a beautiful picture. Yet it has an interesting geologic story. The great depression in which it lies was once a valley formed by the subsidence of a block of the earth's crust—in other words, the valley originated by faulting. The uplifted blocks on each side of it have been so carved and worn by erosion that their blocklike form has long been lost. Erosion also has modified the original valley by supplying the streams with gravel and sand to be carried into it and there in part deposited. The mountains have been worn down and the valley has been partly filled. Possibly the valley at one time drained out to the south. However that may be, at a later stage in its history it drained to the west through a gorge now occupied by the Golden Gate. Subsidence of this part of the coast allowed the ocean water to flow through this gorge, transforming the river channel into a marine strait and the valley into a great bay. Goat Island and other islands in San Francisco Bay suggest partly submerged hills, and such in fact they are.

|

San Francisco. Population 416,912. Seattle 957 miles. |

San Francisco, the chief seaport and the metropolis of the Pacific coast, is the tenth city in population in the United States and the largest and most important city west of Missouri River. The population in 1910 showed a gain of 20 per cent since 1900. The city is beautifully situated at the north end of a peninsula, with the ocean on one side and the Bay of San Francisco on the other. The bay is some 50 miles in length and has an area of more than 300 square miles. The entrance to the bay lies through the Golden Gate, a strait about 5 miles long and a mile wide at its narrowest point.

The site of the city is very hilly, and a line of high rocky elevations runs like a crescent-formed background from northeast to southwest across the peninsula, culminating in the Twin Peaks, 925 feet high. Telegraph Hill, in the northeastern part of the city, is 294 feet above sea level. Here stood the semaphore which signaled the arrival of ships in the days of the gold seekers. The city has been laid out without the slightest regard to topography, consequently many of the streets are so steep as to be traversable only by cable cars and pedestrians. The waters of the bay formerly extended westward to Montgomery Street, and most of the level land in the business section of San Francisco has been made by filling.

Golden Gate Park, containing 1,014 acres and extending westward from the city to the ocean, was a waste of barren sand dunes in 1870, but skillful planting and cultivation have transformed it into one of the most beautiful semitropical public parks in the country. At its west end is the famous Cliff House, overhanging the sea, and a short distance out from the shore are the Seal Rocks, where the great sea lions may often be seen. The Sutro Baths near by, named. after Adolph Sutro, constructor of the famous Sutro tunnel on the Comstock lode, contain one of the largest inclosed pools in the world.

| Commerce. |

San Francisco Bay is the largest and most active harbor of the Pacific coast. Besides the coastwise routes, the port maintains steamship connections with Australia, Hawaii, Mexico, Central and South America, the Philippine Islands, China, and Japan. The direct foreign trade is chiefly with British Columbia, South America, China, and Japan. Although the export grain business has now largely shifted to the ports of Oregon and Washington, San Francisco's permanence as one of the greatest ports of the country is assured by its advantageous position, its wealth of back country, and its command of trans-Pacific and transcontinental trade routes. Three large railroad systems—the Southern Pacific (with two transcontinental lines), the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe, and the Western Pacific—connect it with the East. Lines of the Southern Pacific Co. connect the city with different parts of the State and with the northern transcontinental lines. The Northwestern Pacific serves Mendocino, Sonoma, and Marin counties, on the north, and several smaller lines radiate from different ports on the bay. Only one of the lines mentioned, the Coast Line of the Southern Pacific, actually enters the city. The other roads have their terminals in Oakland and other cities around the bay.

| History. |

The first settlement on the present site of San Francisco dates from 1776. It consisted of a Spanish military post (presidio) and the Franciscan mission of San Francisco de Asís. In 1836 the settlement of Yerba Buena (yair'ba bway'na) was established in a little cove southeast of Telegraph Hill. The name San Francisco was, however, applied to all three of these settlements. The United States flag was raised over the town in 1846, and the population rapidly increased, reaching perhaps 900 in May, 1848. The news of the gold discoveries was followed by the crowds of fortune seekers, so that by the end of 1848 the city had an estimated population of 20,000. From that time on San Francisco has grown rapidly. The first regular overland mail communication with the East was established by pony express in 1860, the charge for postage being $5 for half an ounce. In 1869 the completion of the Central Pacific Railway to Oakland marked the beginning of transcontinental railway communication.

The city suffered from severe earthquakes in 1839, 1865, 1868, and 1906. In respect to property loss the disaster of April 18, 1906, was one of the great catastrophes of history. The actual damage to the city by the earthquake was comparatively slight, but the water mains were broken and it was consequently impossible to check the fires which immediately broke out and which soon destroyed a large part of the city, including most of the business section. Some 500 persons lost their lives, and the estimated damage to property was between $350,000,000 and $500,000,000. Reconstruction began at once, and the city was practically rebuilt in the three years following the earthquake.

| Excursions from San Francisco. |

The Ocean Shore Railroad (station at Twelfth and Mission streets) and connecting automobile line afford a good opportunity to see the geology along the shore from San Francisco to Santa Cruz. The return trip may be made by railroad or stage across the Santa Cruz Mountains. For a distance of 4-1/2 miles north of Mussel Rock (11.9 miles from San Francisco) there is exposed in the bluffs along the coast a remarkable section of the Merced (Pliocene) formation, consisting of about 5,800 feet of highly inclined marine clays, shales, sandstones, conglomerates, and shell beds. In these beds have been found fossil remains of 53 species of marine animals, mostly mollusks, of which three-fourths are still represented by forms living in the ocean to-day. The San Andreas rift (the fracture along which displacement occurred in the San Francisco earthquake of 1906) passes out to sea at the mouth of a little ravine half a mile north of Mussel Rock and is crossed by the railroad. The exposures of the Merced formation along the sea cliffs were much finer before the San Francisco earthquake, which shook down some of the cliffs. From Tobin (18.1 miles) to Green Canyon (21.1 miles) the bed of the Ocean Shore Railroad is cut in bold sea cliffs high above the water and affords not only fine shore scenery but also an excellent section of rocks that probably belong to the Martinez (Eocene) formation. The contact of these rocks with a large mass of pre-Franciscan granite (quartz diorite), which forms Montara Mountain, a bold ridge that extends southeastward from this part of the coast, is crossed by the railroad between Tobin and Green Canyon. At the north end of Seal Cove, opposite Moss Beach station (24.1 miles), the bowldery and fossiliferous sea-beach beds here forming the base of the Merced (Pliocene) and resting on the granite of Montara Mountain are well exposed.

This delightful excursion may be extended down the coast to Pescadero, and the return made by stage across the range and rift zone to San Mateo; or the traveler may continue down the coast to Santa Cruz and return across the range on the Southern Pacific line either by way of the Big Trees and Los Gatos or by Pajaro and Gilroy.

The characteristic thin-bedded radiolarian chert of the Franciscan group is well exposed about Strawberry Hill, in Golden Gate Park. There are good exposures of the chert also on Hunter Point, reached most readily by the Kentucky Street cars from Third and Market streets. The principal rock of the point is serpentine. A mass of basalt in the sea cliffs on the south side presents a remarkable spheroidal and variolitic structure.

The summit of Mount Tamalpais is very easily and comfortably reached by ferry to Sausalito, electric train to Mill Valley, and a mountain railway to the hotel on the top. The ferry trip is one of the best to be had on the bay. The steamer passes close to the small island of Alcatraz, used as a military prison. To the west may be seen the ocean through the Golden Gate. Angel Island, with its interesting glaucophane schists, serpentine, and other rocks, lies to the right as the boat approaches Sausalito. The sedimentary rocks of both islands belong to the Franciscan group and are chiefly sandstone. The trip from Sausalito to Mill Valley by the Northwestern Pacific Railroad gives the traveler opportunity to see some characteristic bay-shore scenery and particularly to note how the waters of the bay appear to have flooded what was once a land valley. Mill Valley is named from an old Spanish sawmill, the frame of which is still standing. The views obtainable from the scenic railway and from the Summit of Mount Tamalpais are extensive and varied. To the south may be seen San Francisco and Mount Hamilton (4,444 feet). To the southeast is Mount Diablo (3,849 feet), through which runs the meridian and base line from which the public-land surveys of a large part of California are reckoned. Nearer at hand is the bay, with its dark-green bordering marshes, through which wind serpentine tidal creeks. Close under the mountain to the north is Lake Lagunitas (an artificial reservoir), and beyond it ridge after ridge of the Coast Range. To the west is the vast Pacific.

From the summit of Tamalpais one sees clearly that San Francisco Bay is a sunken area in which hilltops have become islands and peninsulas. This area is the northern extension of the crustal block whose sinking formed Santa Clara Valley. A later sag admitted the ocean into the valley, and the Golden Gate, formerly a river gorge, became a strait.

Mount Tamalpais has really three peaks: East Peak (2,586 feet), near which the Tavern of Tamalpais is situated; Middle Peak (about 2,575 feet); and West Peak (2,604 feet). From the grassy hills 1-1/2 miles west of West Peak there is a good view of Bolinas Lagoon, through which passes the earthquake rift, but for close views of the rift topography the visitor should walk or drive through the valley between Bolinas Lagoon and Tomales Bay, where the effects of the movement of 1906 are still in many places clearly evident.

Mount Tamalpais is composed wholly of the sediments of the Franciscan group and the igneous rocks usually associated with them, though it is chiefly sandstone. A mass of radiolarian chert occurs near the tavern, and serpentine may be seen at several places beyond West Peak. To one fond of walking and of marine views, a trip on foot to West Peak, thence down the main ridge to Muir Woods (redwoods), and back across the hills to Mill Valley may be heartily recommended. The distance is probably 8 or 9 miles. The Muir Woods, which bear the name of California's greatest nature lover, form a national monument, presented to the nation by William Kent, now Member of Congress from the first California district, for the purpose of preserving untouched by the lumberman one area of redwoods. No fitter memorial could be dedicated to the memory of John Muir, whose writings have contributed so much to the movement for preserving in national ownership, for public enjoyment, some of our finest scenic resources.

|

The earthquake rift. |

The geologic event of greatest human interest on the Pacific coast in modern times was the San Francisco earthquake of 1906. It was produced by a sudden movement of the rocks (faulting) along opposite sides of a fracture which may be traced for many miles in the Coast Range. The fissure existed before the earthquake of 1906, and it is evident from the relations of hills and valleys along it that it has been the scene of earlier and, for the most part, prehistoric movements. The last movement was mainly horizontal and in places amounted to about 20 feet. The San Andreas rift, as this fissure has been called, lies just west of San Francisco, and its course is marked on sheet 13 (p. 90).

The cracks in the soil that mark the line of the last displacement (Pl. XXXIII, B, p. 127) and the parallel ridges and valleys that show older displacements along the fault zone are well displayed in Spring Valley, 13 miles south of San Francisco, and especially near Skinner's ranch, 40 miles northwest of San Francisco.

|

| FIGURE 12.—Earthquake effects at Skinner's ranch, near Olema, Cal. The relative position of the ranch house and trees on opposite sides of the fault plane shows that the horizontal movement was about 15 feet. a, Before earthquake; b, after earthquake. |

To reach Spring Valley the visitor should take a Southern Pacific train to San Mateo (18 miles), where a conveyance may be obtained for a drive through Spring Valley along Crystal Spring and San Andreas lakes.

Skinner's ranch can be reached by the ferry to Sausalito and the Northwestern Pacific Railroad to Point Reyes station, from which the ranch is only 2 miles distant, near Olema. In this region may be seen best the earth cracks along the fault line. Near the ranch house there is striking evidence of the horizontal character of the movement that produced the earthquake. The house formerly had two trees in front of it. The fault line, which trends northwest, passes between the trees and the house, and the trees were moved 1 5 feet to the southeast with reference to the house. (See fig. 12.) There was no perceptible vertical movement nor any change in the water line along Tomales Bay.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

bul/614/sec13.htm

Last Updated: 8-Jan-2007