|

Geological Survey Bulletin 845

Guidebook of the Western United States: Part F. Southern Pacific Lines |

ITINERARY

|

|

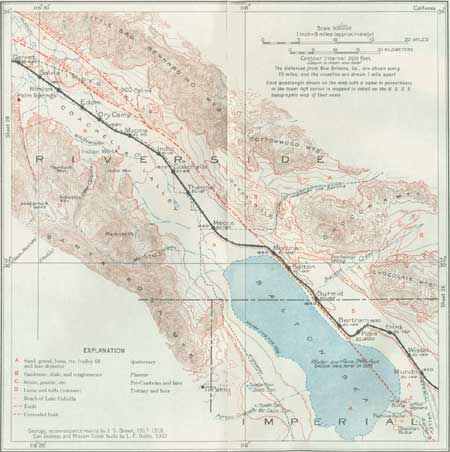

SHEET No. 27 (click in image for an enlargement in a new window) |

At Mundo siding the Salton Sea is in sight (pl. 36, B), and the railroad skirts its north shore nearly to Mecca. It is a weird spectacle in the moonlight.

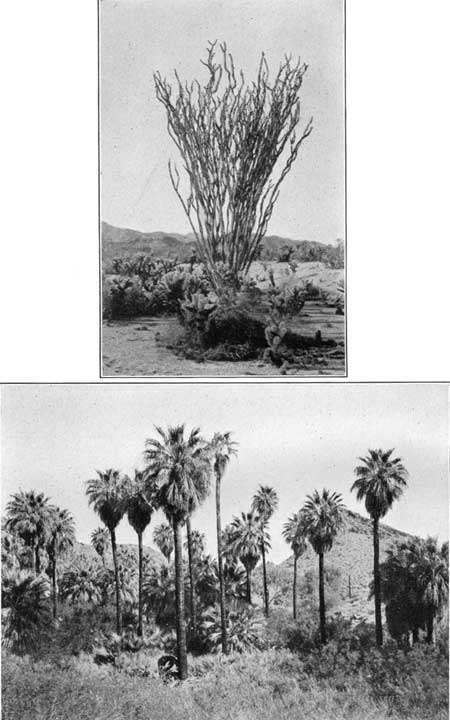

In crossing the Colorado Desert and Coachella Valley from Yuma to Banning striking changes will be noticed in the natural vegetation, especially near Banning, where the xerophilous ("drought loving") Lower Sonoran flora ceases. Near Yuma the desert plants are about the same as those in Arizona, but the sahuaro is absent. The ocotillo (Fouquieria splendens; see pl. 41, A) occurs near the railroad as far west as a point a few miles beyond Glamis, where it recedes to the hillsides on the north, along which it continues to Red Canyon, near Mecca. The paloverde (Cercidium torreyanum) and indigo thorn (Parosela spinosa) continue to Palm Springs, and a few trees like the desert willow (Chilopsis linearis) and the mesquite (Prosopis glandulosa) extend part way though San Gorgonio Pass. The mesquite thrives in the sand dunes in the Indio and Indian Springs region, where a low trailing form (Prosopis juliflora) abounds. The beautiful Washington palm (Neowashingtoniana filamentosa) begins at the Dos Palmas Spring, north of Durmid, and occurs in groups at various springs along the mountain slopes past Indio. There are some groves of this picturesque tree in Palm Canyon, as shown in Plate 41, B. The creosote bush (Covillea) extends all the way up the valley, but in the more sandy places it is widely spaced and greatly stunted. It is the dominant plant near Garnet and Cabazon. The Spanish bayonet (Yucca mohavensis) continues west and is especially conspicuous near Cabazon. The cacti (mostly Opuntia bigelovii, O. basilaris, and O. echinocarpa) extend west along the mountain slopes but do not occur low in the basin, where apparently their altitudinal limit is passed. The ironwood (Olneya tesota) is widely distributed on the dry uplands and bears much mistletoe (Phoradendron californicum), a parasite which also infests the paloverde, mesquite, and other trees.

In the moist alkaline flats of the lower part of the valley the salt bushes (Atriplex canescens and A. polycarpa) and salt grass (Distichlis spicata) are the principal plants, and in wet places near springs rushes (Juncus cooperi), sedges or tules (Scirpus olneyi), arrowweed (Pluchea sericea), and willow (Salix gooddingii) flourish. The willow also forms dense thickets along the overflow lands bordering parts of the Colorado River.

The animals and birds in the desert region of southern California are the same as in southern Arizona and, except the coyote and rabbits, are rarely seen. Large animals occur in the mountains, and deer, sheep, and antelope are occasionally visible in out of the way places.

From Mundo siding to Mortmar siding the railroad is built largely on a bench near the shore of the Salton Sea. A short distance to the northeast of the tracks are hills and badlands of tilted sandstone and shale of Pliocene age. Some distance beyond rise the rugged slopes of the Chocolate and Orocopia Mountains.

At Frink siding is a crusher making "Frink rock" for concrete from detrital material consisting of boulders, mostly of schist, rhyolite, and andesite brought by freshet waters from the mountains. The capacity of the plant is 1,500 tons a day.

|

Bertram. Elevation -189 feet. New Orleans 1,835 miles. |

About 2-1/2 miles northeast of Bertram siding are the "soda mines," where the mineral thenardite, an anhydrous sodium sulphate, with a small amount of the hydrous form (Glauber salts), has been quarried. The mineral occurs in a bed 3 inches to 8 feet thick in the Pliocene sandstones and clays, which here dip about 35° N. The clean mineral is more than 99 per cent pure, and the bed has been traced for 3,000 feet. Several thousand tons a year has been shipped to San Francisco for use in making wood pulp by the sulphite process and also in the manufacture of glass.

From Bertram siding to Mortmar the Orocopia Mountains are conspicuous to the north and northeast, culminating in a dark rounded peak about 3,000 feet high, which is visible for a long distance in the surrounding country. These mountains consist largely of old black schist, but according to Brown andesitic and rhyolitic lavas also occur in them. They are separated from the Chocolate Mountains, to the southeast, by the wide valley of Salton Creek. At their south foot, about 5 miles northeast of Salton siding, is Dos Palmas Spring (Spanish for two palms), a watering place on the old stage road from Ehrenberg to San Bernardino. The water, which is somewhat saline, rises in a marshy pool surrounded by rank vegetation, and on its bank is a small clump of Washington palms. A strip of loose sand marking the old shore of Lake Cahuilla is a notable feature 2 miles south of Dos Palmas Spring.

There are several notable springs along the southwest side of the Salton Basin, due to the escape of ground water under artesian pressure. They are marked by clumps of trees that can be seen across the valley from the railroad, although the distance is 15 miles. One is Kane Spring, nearly due south of Bertram siding. It yields a highly mineralized water rising from uptilted Tertiary strata. Another about 25 miles farther northwest, is Figtree John Spring, which yields good water. It received its name from an Indian who lived there for many years in a grove of fig trees. Near by is Fish Spring, nearly due south of Mecca, where warm water of poor quality forms a large pool and has a flow reported to be 280 gallons a minute. It is an outlet for the artesian flow from the higher part of the Coachella Valley. A small fish, Cyprinodon californensis, lives in the warm water. Near this spring the water line of old Lake Cahuilla (see p. 253) makes a well-marked horizontal band of light-colored travertine on the rocky slope near the base of the mountains and girdling an outlying hill.

Near Mortmar siding the northwest end of the Salton Sea is passed, and in a few miles the route enters the Mecca irrigation district, where an area of considerable extent is irrigated by water pumped from wells of moderate depth.

Most of Coachella Valley is underlain by water-bearing sand and gravel, which in the area below sea level yield artesian flows to many wells. Some water is also raised by pumping. The wells are mostly about Mecca, Thermal, Coachella, and Indio, where the water is used extensively for irrigation. In fact, these places would be only passing sidings were it not for the underground water supply. The artesian water was discovered by the railroad company in 1888 at Thermal and Coachella, and since then 400 or more wells have been sunk, mostly from 500 to 600 feet deep and yielding from 10 to 40 miner's inches (90 to 360 gallons a minute), the amount depending on the size of the well and varying with the locality. The water is contained in sand in the valley fill, and the head is derived from the height of the intake on the sides and higher parts of the valley to the north and is maintained by the impervious cover of fine-grained deposits which occupy the center of the basin. The water is derived from rainfall on the mountains and higher slopes, which passes under ground in the coarse material extending as alluvial fans along the foot of the mountains. Most of the water falling on the mountains runs off the hard rocks and steep slopes but is absorbed by the gravel and sand of the valley fill. Several streams, such as Whitewater Creek, Snow Creek, Tahquitz Creek, Andreas Creek, and the creek in Palm Canyon, sink in that way. In the northern portion of the valley the underground water is of excellent quality, containing only from 150 to 250 parts per million of mineral constituents, but south of a line from the south end of the Santa Rosa Mountains to Salton siding the waters are too saline for use.

The underground water supply about Indio and southward to Mecca is limited in amount, but about 16,000 acres is being irrigated. The crops include melons, dates, grapes, alfalfa, and many other products. The United States Department of Agriculture has made a detailed study of the soils of the Indio area, and many experiments have been made to determine the best crops and proper conditions for their irrigation. Underground waters are pumped at several places west of Indio for irrigation and other purposes. Water furnished by springs and wells east of Salton siding is of too poor quality for irrigation.

|

Mecca. Elevation -188 feet. Population 800.* New Orleans 1,859 miles. |

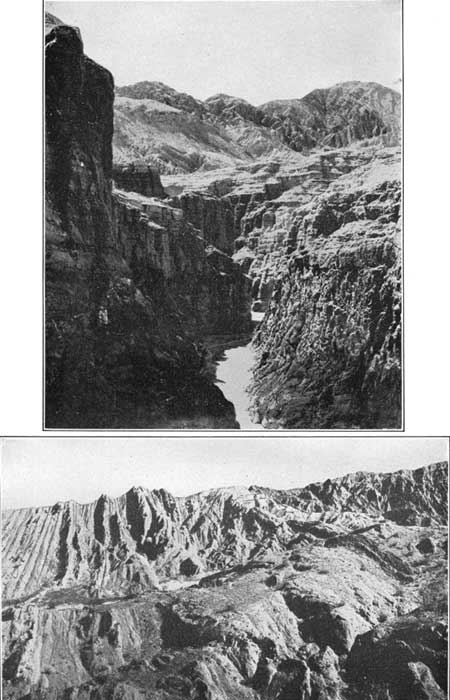

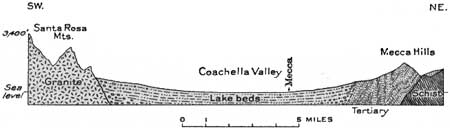

At Mecca (formerly called Walters) the Coachella Valley is a wide alluvial flat extending from the foot of the Santa Rosa Mountains on the southwest to the Mecca Hills on the northeast. The Mecca Hills consist of a 5,000-foot succession of steeply tilted yellowish sandstone and sandy shales with a basal member 1,000 to 1,200 feet thick of brownish-red sandstones and conglomerates. These rocks are well exposed on the Shaver Canyon road east of Mecca. (See also p. 259 and pl. 40, A.) The strata are closely folded, as shown in Figure 62. In Burnt Springs Canyon and near Hidden Spring, east of Mecca, the anticlinal structure of the front ridge is well shown. At Hidden Spring the sedimentary rocks appear to be invaded by a mass of rhyolite. At Shaver Well, about 10 miles east of Mecca, a mass of old schist is exposed in contact with the overlying conglomerate and sandstone. To the east of this place are the high ridges of dark schist known as the Orocopia Mountains. A sandy strip marking the old beach of former Lake Cahuilla is crossed by the highway a few miles east of Mecca, before it enters Shaver Canyon.

|

|

PLATE 40.—A (top), CANYON IN TERTIARY STRATA

EAST OF MECCA, CALIF.. B (bottom), TILTED LATE TERTIARY BEDS IN INDIO HILLS NORTHWEST OF INDIO, CALIF. (Mendenhall.) |

|

| FIGURE 62.—Diagrammatic section across Coachella Valley through Mecca, Calif. By W. C. Mendenhall. |

About Mecca the principal products of irrigation are oranges, dates, and Bermuda onions, which are shipped to all parts of the United States.

Many date palms are growing in the vicinity of Mecca and Indio, where the climate and soil seem particularly favorable. Experimental work on date culture was begun in this area by the United States Department of Agriculture in 1904, utilizing waters pumped from wells. Tests were made of many varieties from the principal date-growing regions of the Old World, but only a few were found to be suitable. The annual rainfall is less than 3 inches, and the humidity is very low. Although the temperature is high for most of the year, it falls below 32° at times, and it has gone to 15°. In midwinter there are light frosts, which seldom continue beyond February. Most varieties of dates are injured by the slightest rainfall or even by dew during the ripening season, so that the complete dryness generally prevailing from August to November is especially favorable to the maturing of the fruit. As the soil at Mecca is nearly pure sand on the old lake beach, care has to be taken to develop sufficient humus and prevent the too rapid sinking of the irrigation water. There is more silt in the soil at Indio. It is necessary also to protect offshoots and seedlings in canvas-covered sheds where suitable temperature and humidity can be maintained. Most dates designed for long keeping and export have to be picked before they are fully ripened and carefully sun dried. Seedling dates are about half females, which alone bear fruit, so that all males in excess of those necessary for pollination are culled out as soon as they can be recognized, which is from the age of 3 to 4 years. Pollination is best accomplished by shaking a frond of male flowers over the female flowers or by tying them together so that the wind will transfer the pollen. Trees usually bear fruit in four years, at first in small amounts and then increasing in size and productiveness for many years. The fruit hangs in great clusters, as shown in Plate 37, A, and ripens in September, October, or November. On the 40-acre experimental date farm of the United States Department of Agriculture, about a mile southeast of Mecca, systematic tests are in progress on the culture not only of dates but of other fruits suitable to the region.

At Mecca the railroad company has a 1,500-foot well which supplies 400 gallons a minute of water of excellent quality, used for locomotives at various places between that place and Glamis. The first well here, bored by the railroad company in 1894, struck an artesian flow similar to that found at Thermal and Coachella several years before.

|

Thermal. Elevation -121 feet. Population 400.* New Orleans 1,865 miles. |

Thermal is a village in the irrigation settlement that extends along the Coachella Valley from Mecca to Indio and beyond. The fine fields of alfalfa and other products of irrigation in this area contrast strongly with the desert conditions in the valley lands which have not been reclaimed. The soil is rich and responds readily to cultivation, and many oranges, dates, and melons are grown, irrigated by water from wells.

|

Coachella. Elevation -66 feet. Population 700.* New Orleans 1,869 miles. |

In ascending the Coachella Valley there are fine views of the adjoining mountains. To the west is the Santa Rosa Range, consisting mainly of hard schists and igneous rocks. To the east are the low but rugged Mecca Hills, consisting mostly of softer sandstones and clays. These and the Indio Hills, their northwesterly continuation, rise about 1,000 feet above the valley plain and show a large amount of badland topography due to rapid erosion cutting steep-sided gullies in soft materials. There are two distinct formations. The lower one, of marine origin and regarded as the same as the late Tertiary beds in the Carrizo Mountains, far to the southeast, crops out in small areas east and west of the mouth of Thousand Palms Canyon and in the northern part of the Indio Hills. It consists of yellow clay with some sandstone and conglomerate and indicates an extension of the waters of the Gulf of California to San Gorgonio Pass in late Tertiary time. In places it carries reefs filled with fossil oysters. It is overlain by several thousand feet of late Tertiary clays, apparently playa deposits, arkosic sandstones, and conglomerates. (Woodring.)78

78At the base of the Tertiary in this region is a conglomerate which at most places near the contact includes many fragments of the underlying schists. The material becomes finer grained farther away from the contact, the conglomerate grading laterally into sand and clay. This gradation is well exhibited in Shaver Canyon, east of Mecca, where near Shaver Well the conglomerate becomes coarser. The sand is mostly an arkosic mixture of quartz and feldspar fragments with more or less mica, all derived from near-by ledges of older rocks. (Brown.)

The strata in the Indio and Mecca Hills are folded in compressed anticlines and synclines, which in general are parallel to the trend of the hills, but the strike is somewhat more to the north and the beds are cut off diagonally by the San Andreas fault, which passes along their south side,79 as shown on sheet 27.80

79Noble, L. F., personal communication.

80At the entrance to Shaver Canyon the beds of soft sandstone and clay dip about 15° SE. The rate of dip increases rapidly, and within half a mile the strata are vertical or slightly overturned in a crushed anticline, as shown in Plate 40, B. Northeast of the axis the dip is to the northeast, and here the anticline is overturned, with vertical dips on its northeast side. This general anticline has been traced southeastward for several miles. East of this anticline there is a broad basin, on the east side of which basal conglomerates rise on the mass of schist that appears at Shaver Well. (Brown.)

The Indio Hills have practically the same structure as the Mecca Hills, except that they consist mainly of two anticlines in a faulted block cut off on the southwest by the San Andreas fault. (Noble, L. F., personal communication.)

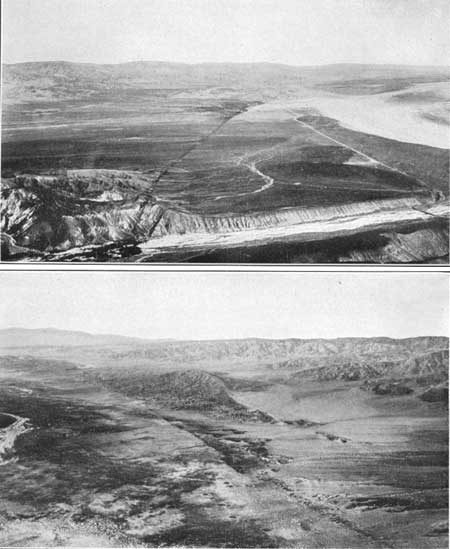

The San Andreas fault is a break in the earth's crust that extends for many miles across southern and central California. Movement along it began far back in the Tertiary period and has progressed at intervals to very recent time.81 It passes along the southwest side of the Mecca and Indio Hills and traverses the valley-fill deposits in the intervals between these ridges, where in places it gives rise to a low cliff. This feature is well shown in the airplane photograph reproduced in Plate 39. Its course, as recently determined by L. F. Noble, is shown on sheets 27 and 28, together with that of another similar break known as the Mission Creek fault; which joins it near Indio.

81That there still is movement along this fault or other faults west of it from time to time is probably indicated by earthquakes in Imperial Valley. One occurred at Brawley March 1, 1930, and another in 1932, and others are recorded at other points at times in Coachella Valley. (See also Beal, C. H., Seismol. Soc. America Bull., vol. 5, pp. 130-148, 1916.) In order to determine the amount of vertical movement on this line of displacement precise levels have been run across this region by the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey through El Centro, Niland, Yuma, and Jacumba, a distance of 158 miles. These, when compared with previous levels, indicate slight vertical displacement a short distance south of Niland (probably on an extension of San Andreas fault), just south of Brawley, and farther south on the supposed eastward continuation of the Elsinore fault. The earthquake of March, 1932, which caused much loss of life and destruction near Long Beach, was due to movement that centered in the ocean, to the west.

|

|

PLATE 39.—A (top), VIEW SOUTHEAST FROM A

POINT 3 MILES NORTH OF BANNING. B (bottom), VIEW NORTHWEST FROM A POINT 2 MILES NORTH-NORTHEAST OF INDIO. Little San Bernardino Mountains in distance. SAN ANDREAS FAULT NEAR BANNING AND INDIO, CALIF. (Continental Air Map Co.). |

The fault trace is less conspicuous along the south side of the Mecca Hills, where in places it is marked by a low bluff, extending as far as Mortmar siding. It is believed by Noble to continue southeastward under the Salton Sea to the mud volcanoes southwest of Niland and thence southeastward by Brawley and Holtville. Another fault beginning in the Indio Hills is believed to extend through Dos Palmas and Frink Springs and continue approximately parallel to the railroad northeast of the sand-hill belt. There are scarps and springs in places along its course.

North of Indio the fault extends along the southwest margin of the Indio Hills nearly parallel to the railroad and from 2 to 3 miles distant.

The older crystaline rocks of the high mountains bordering the Colorado Desert and Coachella Valley are schists and gneisses penetrated by old granite. These schists and granites are cut by younger granitic igneous masses and overlain by a younger series of schists, limestones, and quartzites that are considerably metamorphosed. (Brown, Vaughan, and Frazer.)

|

Indio. Elevation -15 feet. Population 1,500.* New Orleans 1,872 miles. |

About Indio are many trees and fields of alfalfa and various other crops. A large date orchard can be seen just north of the railroad west of Indio, and in the station yard is a fine Deglet Noor date palm (female), imported from North Africa, "the offshoots of which are always true to type." At Indio is the winter resort of the Los Angeles Y. M. C. A., and near by is the attractive resort of La Quinta (keen'ta).

The tilted Tertiary rocks constitute the range of high ridges known as the Indio Hills, which lie about 5 miles northeast of Indio.

In the center of the valley west of Indio and north of Indian Well is a heavy accumulation of dune sand, some of it bearing considerable stunted mesquite. Loose sand is an abundant material in the Coachella Valley, most of it shifted by strong winds that separate the sand from the coarser materials brought into the basin by many side streams. Small sand dunes accumulate, but the material is moved rapidly. The wind-blown sand is a powerful agent of erosion, cutting rocks, metals, and wood; the railroad company finds that the replacement of railroad equipment, telegraph poles, and bridge timbers is a considerable item of expense. It will be noted that many of the telegraph poles are protected by a pile of stones at their base. Sand storms occur occasionally, and if the traveler is not protected he may find them trying. The sand is rounded and worn as it cuts and finally loses most of its abrasive quality. Pebble pavements seen in many desert regions look almost artificial. They owe their origin largely to the removal of sand by the wind so that the pebbles remaining settle down into a pavement that resists further erosion. The surfaces of the pebbles are smoothed and polished by the attrition of sand carried by the wind.82

82Some kinds of igneous rocks and sandstones in desert regions show pitted or cavernous surfaces, with cavities of various sizes up to several inches in diameter, differing materially from the grooving and fluting caused by wind-blown sand. These cavities are believed to be due to inequalities in rock disintegration by solution of the cement or of certain minerals that hold the grains together. Wind and other agencies remove the disintegrated material. The same process has much to do with the isolation and sculpturing of odd-shaped rocks in the desert region. (Blackwelder.)

From Indio northwestward the railroad ascends the Coachella Valley through Myoma, Dry Camp, and Edom sidings. At Edom there is a small irrigated area in which some of the fields are surrounded by tamarisk. This tree was imported from southern Europe, for use in making hedges and windbreaks. As it withstands droughts and thrives under various other adverse conditions, it has proved very useful in the Southwest. As it is not an evergreen and is quite unlike cedar or juniper, the name "salt cedar," by which it is often known, is inappropriate. A wide area of sand occupies the valley from a point beyond Indio to Myoma. To the north are prominent hills of sandstone of late Tertiary age, in front of which passes the San Andreas fault. This fault cuts the sandstone for a short distance near the west end of the range. At intervals along the San Andreas fault and sustained by moisture which it brings to the surface, are small clumps of the Washington palm, mostly visible from the train. Behind the hills about 6 miles northeast of Edom are the Thousand Palm Springs (pl. 41, B), the water of which is believed to rise on the Mission Creek fault. Farther back are the high ridges of the Little San Bernardino Mountains, which consist of a great batholithic mass of granitic rock ranging from pink biotite granite to dark diorite. (Brown.)

|

|

PLATE 41.—A (top), OCOTILLO AND CHOLLA, COACHELLA

VALLEY, CALIF. B (bottom), WASHINGTON PALMS IN PALM CANYON, CALIF. |

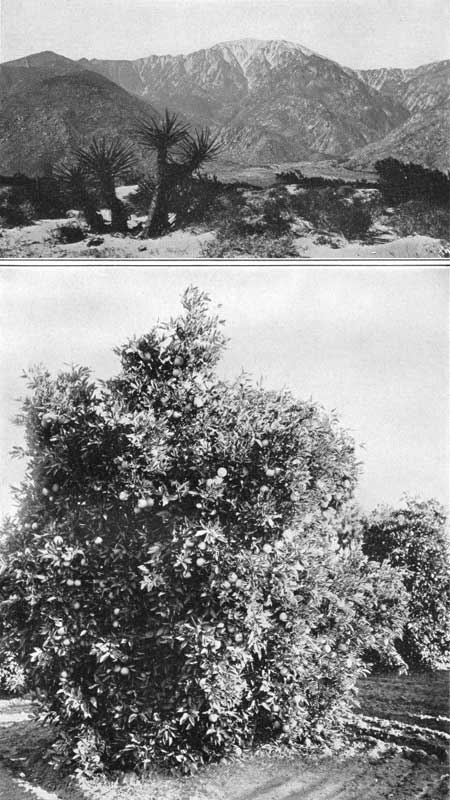

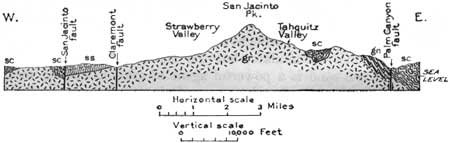

The San Jacinto Mountains, prominently in view to the northwest (pl. 42, A), consist of a huge central mass of granite83 flanked by schistose rocks84 believed to be a contact phase of the granite. (See fig. 63.)

83According to Frazer, the granite mass of the San Jacinto Mountains is mostly a massive light-gray nonporphyritic rock, consisting mainly of orthoclase, microcline, plagioclase, quartz, and biotite, these minerals varying somewhat in proportion and size from place to place. Under the microscope it is seen that the grains are generally fractured but without displacement. The mica constitutes from 8 to 10 per cent and the feldspars 60 to 70 per cent. Some of the rock would be classed as quartz monzonite, granodiorite, and quartz diorite.

84The schists dip away from the central mass at angles mostly from 30° to 60° and in places are overlain by younger schists, 2,600 feet or more thick and varying somewhat in mineralogic character. The younger schists include a small amount of intercalated limestone (marble). These rocks are believed to have been metamorphosed long before the granite was intruded, which may have been in late Jurassic time. The antiquity of their metamorphism is indicated by the fact that they are crystalline far away from the granite contact. Their age may be early Paleozoic, as they resemble rocks of that age in the region to the north. Although the great central mass of granite is massive, there is a marginal phase which is so schistose as to be classed as granite gneiss, a rock extensively exposed on the west side of Palm Canyon and in the region about Andreas Canyon. Its thickness may be 4,000 feet. The intrusive nature of the granite is proved by the contact relation and by the presence of included masses of schist (xenoliths) and limestone. The contact line is very irregular. (Frazer.)

|

|

PLATE 42.—A (top), SAN JACINTO MOUNTAIN, CALIF.,

FROM THE EAST SIDE OF COACHELLA VALLEY. B (bottom), ORANGE TREES IN FRUIT, REDLANDS, CALIF. |

|

| FIGURE 63.—Section through the San Jacinto Mountains, Calif. After Frazer. ss, sandstone; sc, schist; gn, gneiss; gr, granite. |

|

Rimlon. Elevation 400 feet. New Orleans 1,888 miles. |

At Rimlon siding the railroad skirts a large hill of loose conglomerate, mostly covered with white wind-blown sand in which Woodring has found marine Tertiary fossils. These fossils also were found in and near Painted Hill, a ridge east of the Whitewater River not far north of the railroad. There are numerous mollusks in large variety and many Foraminifera.

The Whitewater River is a wide dry wash filled with boulders and sand. It is a flowing stream in the mountains just north of the railroad, but the water sinks rapidly when it reaches the valley fill. In times of flood, however, it runs far down the Coachella Valley and has been known to reach Salton Sea. (Turn to sheet 28.)

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

bul/845/sec27.htm

Last Updated: 16-Apr-2007