|

Idaho Bureau of Mines and Geology Bulletin

Craters of the Moon National Monument, Idaho |

GENERAL VIEW OF THE AREA.

CRATERS OF THE MOON NATIONAL

MONUMENT, IDAHO

By DR. HAROLD T. STEARNS

"An area of about 60 miles in diameter, where nothing meets the eye but a desolate and awful waste, where no grass grows nor water runs, and where nothing is to be seen but lava."1 Undoubtedly Irving's description has reference to the area now known as the Craters of the Moon region of Butte and Blaine counties, Idaho. About 39 square miles2 of this unique volcanic area was proclaimed the Craters of the Moon National Monument by President Coolidge on May 2, 1924. It is administered by the National Park Service of the Department of the Interior. The address of the custodian of the Monument is Arco, Idaho. During the summer season several cabins are available for those who wish to remain in the Monument overnight.

1IRVING. WASHINGTON, The Adventures of Captain Bonneville, U. S. A. Hudson ed., p. 205. New York, 1868.

2Since this report was first published the area has been increased to about 80 square miles, making it one of the largest national monuments under supervision of the National Park Service.

The Monument is reached by a drive of 26 miles from Arco southwest along the Idaho Central Highway. It is easily accessible to tourists on the way to or from Yellowstone National Park. Upon entering the Monument the road leaves the dusty sagebrush desert and enters an area of barren black cinders and lava. Here it winds among the smooth cones and across strips of rough, fresh-looking rock. The similarity of the dark craters and the cold lava nearly destitute of vegetation to the surface of the moon as seen through a telescope gives to these peculiar features their name. The Monument comprises the most interesting and recent part of a vast lava field that covers hundreds of square miles and merges westward into the Columbia Plateau. This plateau covers about 200,000 square miles.

|

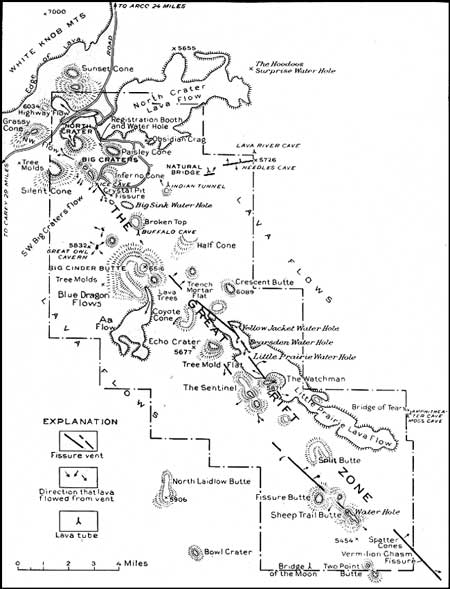

| PLATE I—Sketch Map of the Craters of the Moon National Monument. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

A marvelous view of this desolate lava waste is obtained from the summit of Big Cinder Butte, which rises to an altitude of 6,516 feet and ranks among the largest purely basaltic cinder cones of the world. To the east stretches barren black lava until it fades into the desert haze. Nothing breaks its monotony except one group of grass-covered cones which were not inundated by the floods of lava and which now stand together as a yellow island in a sea of black. Farther east rises Big Butte, the sentinel of the Snake River desert. A little beyond and to the northeast of it, seeming to float in the blue haze, are two smaller peaks known as the Twin Buttes. These peaks have been majestic watchmen on the plain since the first eruptions of lava in the Monument.

|

| PLATE II—View looking southeastward from Big Cinder Butte, showing a double line of cinder cones, many of them grass-covered and all of them vents of numerous flows which unite southward into one great field of lava, lonely and uninhabited. The symmetrical crater bowl on the southeast side of Big Cinder Butte lies in the foreground. Photograph by H. T. Stearns. |

To the southeast from Big Cinder Butte extends a double line of cinder cones, many of them grass-covered and all of them vents of volcanic flows which unite farther south into one great lonely and uninhabited field of lava. Black Top Butte, the farthest in this march of cones, lies approximately 11 miles southeast of Big Cinder Butte. Still farther away are yellow grass-covered cones, and in the distance are barely discernible the snow-covered Portneuf and Bannock mountains.

Four miles to the south of Big Cinder Butte lies a chaos of cinder crags and jagged lava, surrounding a high cinder cone called North Laidlow Butte. Half a mile beyond this cone is Little Laidlow Park, a grass-covered field of ancient lava, appearing pale yellow under the bright midday sun. Farther away on the plain are low lava domes, and in the extreme distance, beyond Snake River, are pale blue mountains along the Idaho-Utah line.

To the west for about 6 miles the lava flowed against the southern spur of the White Knob Mountains, filling the valleys as if they were bays and leaving the ridges like projecting headlands in a black sea. Black and barren as it is, the lava surface has a weird scenic charm.

To the northwest there are crater pits, spatter cones, cinder cones, and lava flows, massed along the Great Rift. Many of the cinder cones are brilliant red at noon but slowly change to purple by sundown. On the tops of many of them are discernible yawning crater pits, which are especially beautiful under the lengthened purple shadows of evening. Beyond this chaotic display of volcanic features rise the impressive White Knob Mountains, covered with grass and streaked with small groves of quaking aspen, golden with autumn foliage and snuggled away in twisted ravines and canyons. Farther north are the snow-clad Sawtooth Mountains, the pride of all Idaho. This grand array of hills and mountains presents an inspiring scene and toward evening becomes pale and soft and velvety, like a staghorn in spring. To those who tarry long, these hills are "never the same, yet are always the same through each changing."

|

|

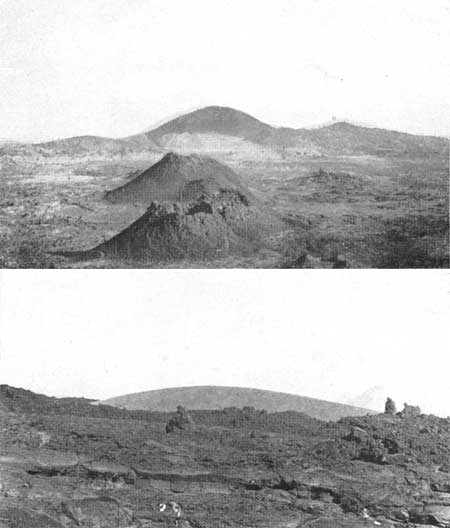

PLATE III—A.—A chain of very symmetrical

spatter cones marks the site of Crystal Fissure, near the end of the

automobile road. Big Cinder Butte in the background. Photograph by H.

T. Stearns. (top) B.—Round Knoll, an ancient grass-covered cinder cone, stands as a yellow island in a sea of black lava. Photograph by H. T. Stearns. (bottom) |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

id/1928-13/sec1.htm

Last Updated: 28-Mar-2006