|

Grant-Kohrs Ranch

Administrative History |

|

INTRODUCTION

In the decade following World War II an expanding and prospering American public frequented its national parks as never before. It was predicted that visitation to the National Park System would double by 1960. However, by the mid-1950s most park facilities had seen no major improvements since the days of the Civilian Conservation Corps, in the 1930s, when great amounts of money and labor had been infused into the System. In the intervening years, during which the nation's attention had been dominated by World War II and the Korean War, roads, bridges, and utilities systems had deteriorated to an alarming degree. Housing for park employees was often worse, consisting of make-shift and barely habitable cabins. [1]

Alarmed at the impacts of this massive influx of people, National Park Service Director Conrad L. Wirth proposed to Congress a ten-year program aimed at rehabilitating the system. This major overhaul of the national parks, termed the Mission 66 Program, was to be accomplished in conjunction with the 1966 fiftieth anniversary of the National Park Service. Both the Eisenhower administration and Congress endorsed Wirth's ambitious plan.

In addition to the general improvement of facilities and the construction of dozens of new visitor centers, hundreds of employee houses, as well as new roads, trails, and maintenance buildings, Mission 66 also affected a dramatic expansion of the Park System. The Survey of Historic Sites and Buildings, administered by the Department of the Interior, was reactivated in 1957 following a hiatus of several years. The program was intended to identify and evaluate nationally significant properties throughout the United States and, with owner consent, designate them as National Historic Landmarks. Ultimately, these were eligible for consideration for inclusion in the System. A similar program was initiated for natural history areas. Even when designated properties lacked the qualities to meet basic criteria to become official units of the System, these inventories nevertheless provided official recognition, and local attention, to thousands of sites that otherwise might have been destroyed inadvertently.

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

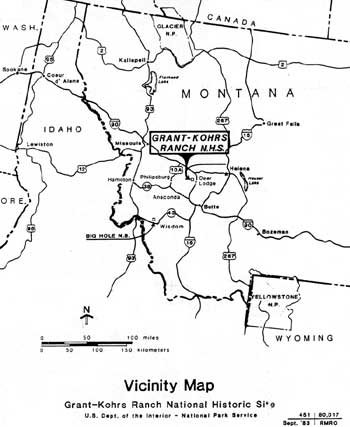

One of the properties singled out during this process was a working cattle ranch owned by Conrad Kohrs Warren at Deer Lodge, Montana. Now known as the Grant Kohrs Ranch, it was the site of one of the Montana's earliest ranches, which eventually became one of the largest cattle raising operations in the West.

The ranch that would eventually burgeon into a cattle empire had humble, if not unlikely, origins in the commerce of the Oregon Trail. "Captain" Richard Grant, a Canadian of Scottish and French ancestry, was already a twenty-seven year veteran of the Northwest fur trade when the Hudson's Bay Company assigned him to manage its affairs at Fort Hall, in what is now the state of Idaho. The company had purchased this post on the Snake River in 1837 for the purpose of extending its wilderness trading empire, as well as to bar American trade from expanding into the Pacific Northwest. By all accounts Grant was a large man, who was "pleasant for an Englishman," according to one Yankee passerby. [2] Grant assumed his new duties as factor in June, 1842,* little realizing then that his tenure there would span more than a decade.

Besides continuing a profitable business trading manufactured goods to the Indians in exchange for furs, Grant fell into a lucrative sideline. By the mid-1840s there was a significant number of emigrants passing over the trail to Oregon. Those who made it that far often were burdened with half-starved, footsore cattle and horses. Although the short-horned cattle were frequently of good English-American blood lines, having been selected to start herds in the promised lands of Oregon and California, these animals were all but useless by the time they reached Fort Hall. Grant saw this as an advantageous opportunity to relieve the emigrants of their lame cattle, and at a handsome profit for the company. An emigrant arriving at the post in 1845 observed that,

The garrison was supplied with flour, which had been procured from the settlements in Oregon, and brought here on pack horses. They sold it to the emigrants for twenty dollars per cwt. [100 lbs], taking cattle in exchange; and as many of the emigrants were nearly out of flour, and had a few lame cattle with them, a brisk trade was carried on between them and the inhabitants of the fort. In the exchange of cattle for flour, an allowance was made of from five to twelve dollars per head. They also had horses which they readily exchanged for cattle, or sold for cash... They could not be prevailed upon to receive anything in exchange for their goods or provisions, excepting cattle or money. [3]

Grant pastured the cattle from one season to the next, time enough for them to regain their weight and health. The following year he would offer west-bound emigrants in need of fresh stock one of these rehabilitated animals in exchange for two head of their worn out cattle. [4]

While Grant showed no hesitation in profiting from the Oregon Trail traffic, some passersby were of the opinion that he was "unwilling to have the country settled by the Americans." [5] Unquestionably loyal to the Hudson's Bay Company, Grant may have simply represented his employer's interests by attempting to discourage emigrants from continuing their journey to the Oregon Territory, a region whose ownership still was disputed by both Great Britain and the United States. Grant no doubt appreciated the potential threat that a great influx of American settlers may have posed to British control of the Northwest. According to other accounts, however, Grant simply informed travelers of the rugged conditions to be encountered on that route, often suggesting that they take the alternate, more easily traveled trail branching off to California. To those who insisted upon going to Oregon, Grant sometimes made an exception by offering to take wagons, for which he had little use, in trade for supplies. The truth of the matter probably lies in a combination of influences, wherein interests of both California and the Hudson Bay Company came into play. [6]

By 1851 an aging Richard Grant recognized that the fur trade was all but dead. When declining health posed a hindrance to his transfer to a more northerly post, as ordered by the Hudson's Bay Company, Grant elected to retire and take up the life of a free mountaineer. He afterward established his residence at an abandoned army cantonment near Fort Hall, from which he conducted personal trading operations with both emigrants and Indians. [7]

Grant's younger adult son from his first marriage, John Francis, was already well-established as a mountaineer and trader in his own right, having struck out independently two years earlier. His taking of a Northern Shoshone wife further enhanced his status and business opportunities among some of the native inhabitants. Based at Soda Springs, east of Fort Hall near the fork of the Hudspeth Cutoff, the Grants continued to actively trade replacement cattle to emigrant farmers, as well as to eager California-bound prospectors. They augmented lucrative summers on the trail by wintering in the mountains along the Salmon River where they traded goods with the Indians. [8]

The Grants traditionally drove their cattle north across the Continental Divide to pasture on the lush grass in the Beaverhead country, in present southwestern Montana. There, sheltered and unmolested by Indians, the stock could recuperate and fatten in a relatively mild climate. In summer part of the herds were separated and driven southward to the trail for use as trading stock to the emigrants.

Reacting to rumors of sedition among the Mormons in 1857, the United States Government ordered a strong military expedition under the command of General Albert Sidney Johnston to Utah to quell the alleged rebellion, if not to subjugate the Mormon population. Latter Day Saints leader Brigham Young immediately ordered his followers to mobilize to resist the threatening invasion. The Mormons quickly took the offensive by sending out armed parties along the trail east of Salt Lake City to destroy potential supply points, including Fort Bridger, and to execute a "scorched earth" policy aimed at denying forage to the advancing federal army.

Meantime, the Grants returned to the Beaverhead region in the fall, happy enough to distance themselves from an impending war. There Richard resided "in a good three room log house" at the mouth of Stinking Water Creek, just north of present-day Dillon, Montana. From this base, Richard Grant and a group of former Hudson's Bay employees continued trading on the emigrant road, as well as with the Indians in the region. [9]

John Grant remained for a time near his father's camp, later moving to the Deer Lodge Valley for the winter of 1857-58. When a government contractor negotiated a deal to purchase two hundred head of cattle from Grant to supply Johnston's column at Fort Bridger, Grant declined to deliver the herd for fear the Saints would retaliate against him. By this time Grant considered himself a permanent resident and businessman in the region and thus had no desire to make enemies of the Mormons, with whom he had to deal, war or not. Salt Lake City was, in fact, his principal point of supply. Despite the loss of this sale, Grant later chanced selling the troops a few dozen horses, which he drove to Fort Bridger the following spring. [10]

The elder Grant, also concerned for the safety of his property, packed his goods and trekked farther north to Hell Gate, in the vicinity of modern-day Missoula, early in 1858. There in the Flathead Indian country of the Bitterroot he continued to raise cattle successfully for another three years, until a particularly hard winter decimated his herd. His roving days came to an end when he journeyed to The Dalles in Oregon to obtain supplies over the winter of 1861-62. On the return trip in the spring, Grant suffered from over-exertion and died before reaching home. [11]

In the summer of 1858 Johnny Grant, as he was universally known, returned to the Bitterroot, where he had left his cattle on shares with John M. Jacobs during his trip to Fort Bridger. He then drove this stock back to Henry's Ford, near Fort Bridger, where he happily discovered that the other traders had disposed of their entire herds to supply the Utah Expedition. As a result, Grant's competitors were left with only the emaciated cattle they had been able to buy from passing emigrants that season, When Johnny arrived with his fresh herd that fall, he immediately began trading his fat steers, at the rate of one head for two. That winter he chanced grazing these cattle in the vicinity, rather than returning to Montana, so that by the next spring he had a sizeable herd to offer the emigrants.

Although Johnny Grant was in an advantageous trading position during the summer of 1859, he perceived that the traffic over the trail was less than it had been previously, a factor that likely prompted him to return to the Deer Lodge Valley that fall. [12] The relatively mild climate, clear mountain streams, and an endless abundance of rich grass made it a near-perfect place for raising cattle. It was a good place to settle down with his family, which by this time had grown to include three Indian wives and a number of children. His rough-hewn log cabin stood at the mouth of Little Blackfoot Creek, about twelve miles north of the present ranch. [13]

Despite the prosperity he found in the Deer Lodge Valley, Grant discovered that it was a lonely existence for a family accustomed to interacting with people during the Fort Hall days and later with their mountaineer clan on the Beaverhead. A few Indians and even fewer white men occasionally passed through, but none stayed. Bored by the solitude, Johnny decided to journey back to the Oregon-California Trail to see if he could induce some of the west-bound settlers to follow him back to Montana. His glowing descriptions of the country persuaded about a dozen families to redirect their destinies to the Deer Lodge Valley. These few formed the nucleus of a settlement christened, appropriately, "Cottonwood." Later, it would re-named Deer Lodge.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

grko/adhi/adhi0.htm

Last Updated: 28-Aug-2006