|

INDEPENDENCE National Historical Park |

|

The Story of a Symbol

The Liberty Bell is the most venerated symbol of patriotism in the United States; its fame as an emblem of liberty is worldwide. In the affections of the American people today it overshadows even Independence Hall, although veneration for the latter began much earlier. Its history, a combination of facts and folklore, has firmly established the Liberty Bell as the tangible image of political freedom. To understand this unique position of the bell, one must go beyond authenticated history (for the bell is rarely mentioned in early records) and study the folklore which has grown up.

The known facts about the Liberty Bell can be quickly told. Properly, the story starts on November 1, 1751, when the superintendents of the State House of the Province of Pennsylvania (now Independence Hall) ordered a "bell of about two thousand pounds weight" for use in that building. They stipulated that the bell should have cast around its crown the Old Testament quotation, "Proclaim liberty throughout all the land, unto all the inhabitants thereof." Most likely, this phrase was chosen in commemoration of William Penn's Charter of Privileges issued 50 years earlier.

Thomas Lester's foundry at Whitechapel, in London, was the scene of casting the bell. Soon after its arrival in Philadelphia, in August 1752, the brand new bell was cracked "by a stroke of the clapper without any other violence as it was hung up to try the sound." At this juncture, those now famous "two ingenious workmen of Philadelphia," Pass and Stow, undertook to recast the cracked bell. After at least one recorded failure to produce an instrument of pleasing tone, their efforts were successful, and, in 1753, the bell began its period of service, summoning the legislators to the Assembly and opening the courts of justice in the State House.

Speaker's desk in Assembly Room, with Syng inkstand, "Rising Sun" chair, and Peale portrait of Washington. |

With the threat of British occupation of Philadelphia in 1777, the State House bell and other bells were hastily moved from the City to prevent their falling into British hands and being made into cannon. Taken to Allentown, the bell remained hidden under the floor of the Zion Reformed Church for almost a year. In the summer of 1778, upon the withdrawal of the British, it was deemed safe to return the bells to Philadelphia.

By 1773, the State House steeple had become so dangerously weakened that it was removed in 1781 and the bell lowered into the brick tower. Some 50 years later, in 1828, when the wooden steeple was rebuilt, a new and larger bell was acquired. The old bell, almost for gotten, probably remained in the tower. The new one was obtained, perhaps, because the original had either cracked or had shown indications of cracking. Traditionally, the fracture occurred while the bell was being tolled during the funeral procession of Chief Justice John Marshall some 7 years later. In 1846, an attempt was made to restore the bell's tone by drilling the crack so as to separate the sides of the fracture, This attempt failed. The bell was actually tolled for Washington's birthday, but for the last time, for the crack began to spread.

Now that the bell was mute, useless as a summoner or sounder of alarms, it began to assume a new and more vital role. Over the years it came to be a symbol of human liberty—a very substantial symbol of 2,080 pounds of cast metal—inscribed with the Biblical admonition to "proclaim liberty."

An early use of the Liberty Bell as a symbolic device. From R. H. Smith, Philadelphia As It Is, 1852. |

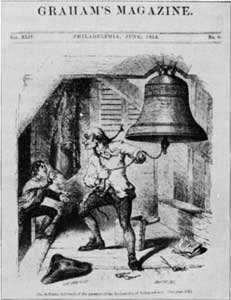

"The Bellman informed of the passage of the Declaration of Independence." Lippard's legend of the Liberty Bell was incorporated by Joel Tyler Headley in hisLife of George Washington, which ran serially in Graham's Magazine in 1854. This illustration appeared in the June issue. |

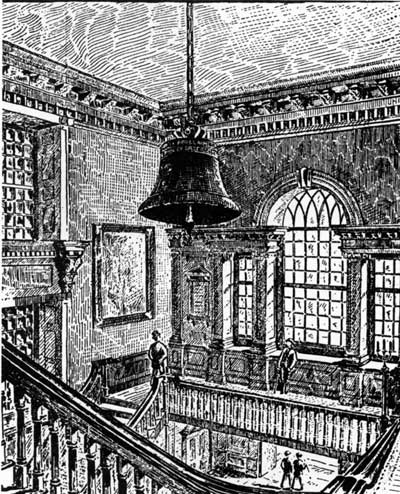

Between 1854 and 1876, the Liberty Bell stood on display in the Assembly Room on a 13-sided pedestal representing the Thirteen Original States. Sketch by Theo. R. Davis in Harper's Weekly. July 10, 1869. |

It is difficult to find the exact beginnings of this veneration for the Liberty Bell. Independence Hall, the building with which it is so intimately associated, began its evolution as a patriotic shrine about the time of Lafayette's visit in 1824, but the bell, rarely mentioned earlier, still received no notice. Illustrative of this lack of interest, perhaps, is the late 19th-century tradition, only recently disproved, that in 1828 the Liberty Bell was offered as scrap metal valued at $400 in partial payment to the manufacturer for the new State House bell.

Probably the first use of the bell as a symbolic device dates from 1839. In that year, some unknown person apparently noted the forgotten inscription on the bell. This was immediately seized upon by adherents of the antislavery movement who published a pamphlet, entitled The Liberty Bell. This is also the first known use of that name. Previously, the bell was called the Old State House Bell, the Bell of the Revolution, or Old Independence. That publication was followed by others which displayed the bell, greatly idealized, as a frontispiece. Thus the bell became identified with early antislavery propaganda, invoking the inscription of a promise of freedom to "all the inhabitants" During this time, it is interesting to note, the symbolism of the bell served a narrow field; little, if any, thought was given it as a patriotic relic.

But patriotism was the next logical step. In the first half of the 19th century the bell became the subject of legendary tales which it has not been possible to verify. These legends have been recited in prose and poetry; they have found their way into children's textbooks; and they have contributed greatly to rousing the patriotic enthusiasm of succeeding generations of Americans. Accepted by all classes of people, these legends have done more than anything else to make the bell an object of veneration.

From 1876 to 1885, the bell hung in the tower room

from a chain of 13 links.

Wood engraving in David

Scattergood, Hand Book of the State House, Philadelphia,

1890.

The patriotic folklore apparently began with George Lippard, a popular novelist of Philadelphia. It was Lippard who wrote that most thrilling and irrepressible tale of the bell, the vivid story of the old bellringer waiting to ring the bell on July 4, 1776. This tale first appeared in 1847 in the Philadelphia Saturday Courier under the name, "Fourth of July, 1776," one of a collection called Legends of the Revolution.

The popularity of Lippard's legend soon brought imitations. The noted Benson J. Lossing, gathering material for his popular Field Book of the Revolution, visited Philadelphia in 1848 and recorded the story. This gave the legend historical credence in the minds of Lossing's host of readers. Taking the story presumably from Lossing, Joel Tyler Headley, another well-known historian, included it with certain variations of his own in his Life of George Washington. which was published first serially in 1854 in Graham's Magazine and then in book form.

Firmly established as history by Lossing and Headley, Lippard's story also found poetic expression. The date of the first poem on this theme has not been established, but, once written, it found its way into school readers and into collections of patriotic verse. The most widely read was probably G. S. Hillard's Franklin Fifth Reader, issued in 1871, although the poem had been in popular use for some time before. Beginning with "There was a tumult in the city, in the quaint old Quaker town," the poem became a popular recitation piece which every schoolboy knew. The best known lines read:

Hushed the people's swelling murmur,

Whilst the boy cries joyously;

"Ring!" he's shouting, "ring, grandfather,

Ring! Oh, ring for Liberty!"

Quickly at the given signal

The old bellman lifts his hand.

Forth he sends the good news, making

Iron music through the land,

The Liberty Bell in a glass case, 1895—1915. From victor Rosewater, The Liberty Bell Its History and Significance, D. Appleton and Co., New York, 1926. Courtesy Appleton-Century-Croft Inc. |

The growing legend of the Liberty Bell aroused curiosity in the relic itself, hidden from view in the tower. It was consequently brought down to the first floor of Independence Hall. In 1852, during a convention of delegates from the Thirteen Original States in Independence Hall, the bell was placed on a temporary pedestal in the Assembly Room—the east room. Two years later the temporary platform was replaced by a massive pedestal having 13 sides ornamented by Roman fasces, liberty caps, and festooned flags. The bell was topped by Charles Willson Peale's mounted eagle.

In this position the Liberty Bell remained until a more intense interest, awakened by the approaching celebration of the Centennial Anniversary, caused it to be moved to the hallway. Here it was mounted on its old wooden frame which had been found in the tower. A plain iron railing enclosed the bell and frame.

The bell stayed in this location for only a short time. A few years later it and the frame were placed in the Supreme Court Chamber—the west room—near one of the front windows. Displaying it in its heavy wooden frame evidently proved unsatisfactory, because the bell itself was practically concealed. The next move, therefore, was to suspend it from the ceiling of the tower room by a chain of 13 links.

Probably because the inscription was difficult to read while the bell was suspended from the chain, it was lowered about 1895, placed in a large, glass-enclosed mahogany case, and again put in the Assembly Room. For 20 years it remained in this case, located part of the time in the Assembly Room and part of the time in the tower room. Finally, it was decided that visitors should be permitted to touch the bell, which was removed from the glass case in 1915 and exhibited on a frame and pedestal. With the whole arrangement on wheels, it could be quickly rolled out of the building in an emergency. This is the manner in which it is displayed today. Located just inside the south, or tower, door, the Liberty Bell is illuminated at night so that visitors may see it from Independence Square.

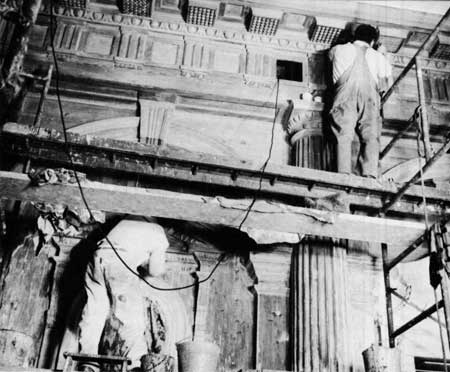

Architectural investigation in Independence Hall,

1956. Top: Removal of paint and restoration of woodwork. Bottom: Detail

of hand-carved decoration after paint removal.

The growing importance of the Liberty Bell as a patriotic symbol aroused popular demand for its movement around the country so that more people could see it. The first long journey was in the winter of 1885 to New Orleans and through the South. Later trips took the bell to Chicago in 1893, to Atlanta in 1895, to Charleston in 1902, to Boston in 1903, and to San Francisco in 1915. On each trip the arrival of the bell was the occasion for celebrations by patriotic groups and citizens, many of whom traveled long distances to see and touch the venerated relic. During these trips, however, the crack in the bell increased, and finally its condition became so dangerous that all future travel had to be prohibited.

The affectionate reverence inspired by the Liberty Bell is demonstrated by the endless stream of visitors who come to see it, touch it, or simply stand quietly beside it. No other patriotic relic in America has had a more distinguished visitation. Almost every President of the United States since Abraham Lincoln has come to Independence Hall to pay his respect to the Liberty Bell. Statesmen and great military leaders of the world have joined the masses of ordinary people in honoring it. Poets and other literary figures have attempted to express the meaning of the bell, and John Philip Sousa, the "March King," composed a Liberty Bell March. It has been pictured on postage stamps, 50-cent pieces, and on national bond drive posters.

The Liberty Bell has served to arouse the patriotic instincts of more than one generation of Americans. It is today surrounded by a cloak of veneration. Even more, it has come to be regarded by countless millions throughout the world as a great symbol of freedom, liberty, and justice.

|

| History | Links to the Past | National Park Service | Search | Contact |

|

Last Modified: Mon, Dec 2 2002 10:00:00 am PDT |