INTRODUCTION

By Marian Albright Schenk

FOREWORD

By Dean Knudsen

SECTION 1

Primary Themes of Jackson's Art

SECTION 2

Paintings of the Oregon Trail

SECTION 3

Historic Scenes From the West

|

| During the 1935 Gettysburg veteran's reunion, William Henry Jackson was photographed in front of his tent with his new 35mm camera. Jackson jokingly referred to this camera as his "vest pocket" or "miniature" camera. (SCBL 978) |

Section 3: Historic Scenes from the West

THE CATTLE INDUSTRY

Cattle have played a key role in the frontier economy ever since their introduction by Spanish explorers in the Sixteenth century. The rolling, grass-covered prairies offer an environment in which cattle can thrive in their millions, but if they cannot be brought to a ready market they are of little value to the producers.

|

| In February of 1867 Jackson and a traveling companion named Bill Maddern had to save themselves from a cattle stampede by waving their jackets and shouting at the top of their lungs. This incident took place in the Mojave Desert. (SCBL 141) |

Thus was born the cowboy and the cattle drive. Cattle drives have actually been a feature of the American economy for centuries. Herds of cattle were moved from Florida up into New England as early as the American Revolution, but it is the Texas cattle drives of the 1860s and 1870s that are credited with the development of the American cowboy.

In spire of the long hours and short life expectancy, the romantic life of a cowboy has come to play a dominant role in the literature of the West. Popular authors such as Owen Wister, Zane Gray and Louis Lamour have created fictional characters of few words and mighty deeds who wanted nothing but to be left to their thoughts on the open range.

Of course, the reality of a cowboy's life was anything but romantic. As a rule the cowboy's day was harsh and dangerous. By its very nature, the job offered a wide variety of ways to get killed or crippled and very few ways to grow old gracefully. William Henry Jackson first encountered the West's cattle culture as he began his journey back east in 1867. As he describes it:

Crossing a broad valley grown over with sagebrush and cactus, we saw a sizeable herd of cattle off to our right. Then we noted that the animals were moving toward us. Soon the thudding of their hoofs had increased to an ominous rumble, and we realized that the longhorns were preparing to stampede. With no mounted herdsmen in sight to cut them off Bill and I had to stop them—or else.

We shouted and waved our hats and jumped into the air. We yelled and whirled our coats and jumped even higher. Still they came on, until not more than a hundred feet lay between the animals and ourselves. Then the herd leader, a black bull, slowed.

At fifty fret he was dubious about continuing—but the pressure from behind forced him to within fifteen or twenty feet of us before we felt even moderately safe.1

Beginning in 1849 the California Gold Rush offered an irresistible market of hungry miners, and drives of Texas beef were made across the Southwest.2 The two most famous cattle routes came into use after the Civil War: the Chisholm Trail which drove due north from Texas into central Kansas; and the Goodnight-Loving Trail which swung west into New Mexico before turning north into Colorado.3

It was on these epic drives that the myth of the American cowboy took shape. Unfortunately the myth does not take into account either the drudgery and bone-numbing fatigue that actually characterized life on a cattle drive, or the diverse contributions made by other cattle drives to the American economy.

1. Jackson, Time Exposure, 152-153.

2. Garnet M. Brayer and Herbert O. Beater, American Cattle Trails, 1590-1900 (Denver: The Smith-Brooks Printing Co., 1952), 39.

3. Ibid., 55f.

|

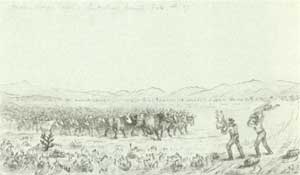

| The Chisholm Trail. Signed and dated 1941. 25.4 x 38.1 cm. (SCBL 163) |

|

scbl/knudsen/sec3h.htm Last Updated: 14-Apr-2006 |

|