Historical Background

| August 13-17 1805 |

A fortuitous meeting

About a mile farther down the trail, now dusty and apparently recently traveled by men and horses, Lewis and his group suddenly came upon a native woman and two young girls, only 30 paces away. Until then, ravines had prevented the two parties from seeing each other. One of the girls immediately took flight, but her companions remained. Lewis laid down his gun and advanced toward them. Alarmed, they sat down, holding their heads "as if reconciled to die which the[y] expected no doubt would be their fate." Lewis walked up to them, took the older woman by the hand, raised her up, and repeated the expression "tab-ba-bone." At the same time, aware that the rest of his body was so tanned he resembled an Indian, he lifted his shirt sleeve to show his white skin and then passed out presents. These actions had a calming effect. Drouillard, McNeal, and Shields came up.

Lewis, fearful that the second young girl, who was watching from a distance, might leave and alarm her camp, directed Drouillard to tell the older woman in sign language to call back the younger one. She did this. Lewis gave the newcomer gifts, and used vermilion from his trade goods to paint the cheeks of all three—a practice Sacagawea had said signified peace to the Shoshonis. Drouillard indicated to the woman and girls that Lewis wanted them to lead him to their village to see their chief. They readily assented and led the way down the trail along the Lemhi River.

When about 2 miles had been traversed, a band of 60 braves galloped up. They were responding to an alarm carried to the village by the first group of Indians that the Lewis complement had seen, and were riding out to meet what they thought was a Blackfeet war party. Lewis, putting down his gun and carrying the flag, advanced a short distance ahead of his group. Tension subsided as soon as the three women informed the chief, Cameahwait, of the friendliness of the white men, none of whom this band of Shoshonis had ever seen. [108]

Greetings were exchanged until Lewis grew "tired of the national hug." After the pipe was smoked, Lewis presented the chief with the flag and other gifts, and the Indians painted the four visitors. Every one then moved to the Indian village, about 4 miles northward on the east bank of the Lemhi River. Lewis and his companions were made comfortable in a skin tipi. It was the only one in the village; the other lodges were also conical but constructed of willow brush. A gift of a piece of salmon from one of the natives that evening convinced Lewis beyond doubt that he was on waters leading to the Columbia.

Realizing mounts would be needed to reach navigable waters of that system, the next day Lewis carefully examined the large horse-herd, which numbered around 700. He observed that most of the animals, some of which carried Spanish brands, were in good condition and would "make a figure on the South side of James River or the land of fine horses." The herd included about 20 mules, also of Spanish origin and highly valued by the Indians.

Despite their wealth in horses, the Shoshonis were near starvation, living on roots, berries, fish, and an occasional antelope or deer. Thus, despite the general hospitality extended to them, Lewis and his men had to eat their own limited rations, supplemented by berries and what game they could find.

Drouillard could communicate well with Cameahwait in sign language. Lewis experienced difficulty in persuading the chief to provide horses and return with him to the point where he planned to meet Clark and the boat party, at the junction of Horse Prairie Creek and the Red Rock River. Lewis was afraid that if he lost contact with the Indians he might not find them again. The Shoshonis mortally feared meeting the Blackfeet, who raided from as far away as present Canada, as well as the Minitaris. Only that spring a Blackfeet war party had attacked, killed, or captured 20 men; stole many horses; and destroyed all the skin tipis except the one Lewis and his men occupied. But at last, employing all the diplomacy at his command, including the questioning of Indian courage, Lewis convinced Cameahwait to make the crossing and bring along a group of his braves.

On August 15 the trek began back through Lemhi Pass to the planned rendezvous point with Clark, reached the next day. Lewis was alarmed to find that Clark and his party, who had been making only slow progress up the rugged Beaverhead, had not arrived yet. This presented a dilemma, for the Shoshonis suspected treachery. Lewis resorted to all sorts of stratagems. He turned over the party's guns to Cameahwait, tried to deceive him into believing that a note he had earlier left for Clark telling him to wait there was actually from Clark saying he was coming up, and promised to show him a black man. Everything, possibly even the success of the entire expedition, depended on Clark's arrival the next morning, particularly because Sacagawea was with him and she would reassure the Shoshonis.

When dawn did not bring Clark, the distraught Lewis dispatched Drouillard, accompanied by several mounted braves, with a note urging all haste. Two hours later, an Indian who had strayed a short way from camp, ran in and stated that the white men were coming in boats.

|

|

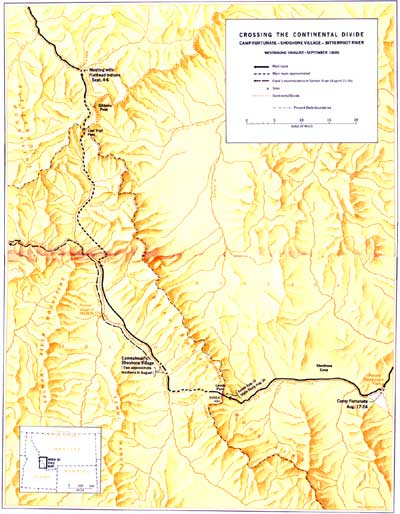

Crossing the Continental Divide — Camp Fortunate, Shoshone Village,

Bitterroot River. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

AT 7 o'clock that same morning Clark, his feet much improved and eager to contact Lewis or the Shoshonis, had set out ahead of the boat party with Charbonneau and Sacagawea. The latter, in her home country, was in the lead. They had not gone more than a mile when Clark saw her stop, dance with joy, signal to him, point to some mounted Indians approaching, and start sucking her fingers to signify that they were her own people. After greeting Drouillard and his companions, the entire party moved forward. About noon, as it approached the Lewis-Cameahwait camp, a young Indian woman ran out and embraced Sacagawea. As a child, she had been captured by the Minitaris at the same time as Sacagawea but had escaped.

The boat party had ended its last day of toil westward on the waters of the Missouri drainage. There were good reasons for the tardy arrival. Daily progress had finally averaged only 4 or 5 miles. It had been necessary literally to drag the canoes along the shallow, boulder-covered bed of the Upper Beaverhead, by this time no more than a large creek. Accidents and injuries were frequent. Clark ignored repeated entreaties to leave the canoes and proceed overland.

|

http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/lewisandclark/intro41.htm

Last Updated: 22-Feb-2004