.gif)

MENU

Design Ethic Origins

(1916-1927)

Design Policy & Process

(1916-1927)

![]() Western Field Office

Western Field Office

(1927-1932)

Decade of Expansion

(1933-1942)

State Parks

(1933-1942)

|

Presenting Nature:

The Historic Landscape Design of the National Park Service, 1916-1942 |

|

IV. THE WORK OF THE WESTERN FIELD OFFICE, 1927 TO 1932 (continued)

A PROGRAM OF LANDSCAPE NATURALIZATION

The naturalistic landscape gardening practices that had evolved in the 1920s called for the planting of groupings of native trees, shrubs, and grasses along roadways, construction sites, and eroded areas and the removal of vegetation for fire control and beautification. As construction took place in the parks, trees and shrubs were removed from the construction sites of buildings, roads, overlooks, and parking areas and transplanted in temporary nurseries or on the sites of completed construction. This process of transplanting and replanting became known as "landscape naturalization" by 1930. At this time, the National Park Service under the leadership of Harold C. Bryant banned the introduction of exotic plants into the parks and encouraged the elimination of exotics already growing in the parks. This change occurred at the same time that park service landscape architects were developing a process of flattening and rounding slopes to curb erosion and naturalize park roadways.

National park designers recognized the benefits of planting in the late 1910s and early 1920s. Charles Punchard had encouraged Yosemite's park superintendent and concessionaires to use techniques of the Arts and Crafts movement to conceal artificial surfaces with a mantle of vines and other native plants. He had drawn attention to the need to replant the giant sequoias of Sequoia National Park in 1919. In 1925, Hull called for reforestation to screen or mask unsightly objects or burned over areas. That year, in cooperation with the Public Health Service, Hull had used plantings to rehabilitate the Apollinaris Spring in Yellowstone, making the area more attractive and sanitary, and recommended that springs in other parks be studied with the idea of "increasing their usefulness and beauty." It was not until the end of the decade, however, that planting was done in a routine or serious manner either as a consequence of construction or as an effort to add to the scenic beauty of the park. [81]

In spring of 1927, Vint hired Ernest Davidson, who had substantial experience in planting and transplanting trees and shrubs. Davidson's first assignment was to supervise the planting of trees at the Gardiner Gate at Yellowstone. Here the year before, Vint and the concessionaire had discussed plans to redesign the approach to the Gardiner Gate and build new company garages. Davidson drew up a planting plan that screened the company garages from public view and restored a natural appearance to the area in front of the entry arch where a reflecting pool had been filled in. Concerned by the loss of vegetation, he transplanted trees and shrubs in the Mammoth Hot Springs and Canyon campgrounds. By September, Davidson's plantings had taken hold with only a few having died. Davidson believed that if proper care was given to transplanted materials for two months one could successfully transplant even late in the season when the leaves were fairly well developed. Vint's decision to hire Davidson may well have been influenced by the recognition that a planting program could solve many of the park service's landscape problems. [82]

Later that year at Mount Rainier, Davidson began the first serious planting program in a park village. He and a small crew planted evergreen trees, shrubs, and ferns and constructed some rockwork near the grand log arch at the Nisqually Entrance. By planting alders, vine maples, and evergreens, they screened the old switchback road from the view of the new Nisqually Road. Davidson's projects for Longmire Village included planting plans for four new cottages, which called for simple foundation plantings that the residents could plant and care for. At the campground, soil was hauled in to grade the grounds around the new community building, and small evergreens, maples, alders, and similar shrubs were planted around the building. Ferns were planted about the foundation and the entry walk, which was outlined by rock cobbles embedded in the soil. This work improved the visitor's access to the site, erased the scars of construction, and created the illusion that the woodland had never been disturbed. The thick forests at Longmire consisted of a canopy of mature trees that consisted predominately of western hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla), Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii), western red cedar (Thuja plicata), and Alaskan cedar (Chamaecyparis nootkatensis) and an understory of herbaceous plants and shrubs that included salal (Gaultheria shallon), sword fern (Polisticum munitum), Oregon grape (Berberis nervosa), and vine maple (Acer circinatum). Davidson also conducted several experiments with the planting of sloped banks of the new roads, by planting the root cuttings of various shrubs and plants including brake ferns (possibly the cliffbrake fern, Pellaea glabella), salal (Gaultheria shallon), and huckleberry (Vaccinium spp.). [83]

Davidson continued his planting program at Mount Rainier in 1928, taking special interest in the new administration building, which was taking form on the village plaza according to his designs. A year with the park service had shown Davidson that planting was not considered a serious part of park development and needed funding. Davidson wrote to Vint,

It seems extremely difficult to establish the fact that landscape planting is work and must be handled on the same plans as any construction and that it is important work, if we expect to make a material change for the better in some of our most prominent park community appearances. This does not especially apply to any park, but to all in which I have had experience. [84]

Mount Rainier's Superintendent Owen Tomlinson favored the planting program and would become one of the strongest advocates of such work. He issued a memorandum to all park residents encouraging them to use native flowers, shrubs, and trees and offering them Davidson's services in preparing planting plans for their residences. Tomlinson praised many of Mount Rainier's native plants for their ornamental purposes. [85]

Davidson and Merel Sager spent a substantial amount of time at Mount Rainier in 1928 working on landscaping projects, in addition to supervising the construction of roads, guardrails, and bridges along the Yakima Park Road. At Paradise, Sager planted the entrance to the new community building with fir trees and other evergreens six to eight feet high. These plantings apparently included subalpine fir (Abies lasiocarpa), Pacific silver fir (Abies amabalis), and Alaskan cedar (Chamaecyparis nootkatensis), which came through in "splendid condition" and "greatly improved the appearance of the building." In this subalpine terrain on a ridge with sparse vegetation, the trees were planted in small groups along the front of the building and created vertical accents that echoed the massive vertical timbers of the building that repeated across the facade. Davidson and Sager also assisted the concessionaire in planting the grounds of the Paradise Inn with trees transplanted from the construction site for the new lodge and housekeeping cabins. [86]

The new administration building, the centerpiece of the plaza at Longmire, was near completion and ready for grading in October 1928, when funds ran out. Davidson scraped together enough money and labor to plant a screen of six- to fourteen-foot evergreens, including western hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla) and Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii), at the northeast corner to block the view of the duplex dwelling from the plaza. These supplemented the few trees untouched during construction, the most prominent of which was the stalwart Douglas fir on what was to become the front lawn. [87]

In 1929, with the grading and development of the plaza, the grounds of the administration building were graded and a lawn was seeded. At the same time, landscape improvements were made throughout the village. Over a two-week period in November 1929, several hundred trees and shrubs were transplanted by a crew of four men supervised by Davidson. Stone curbs consisting of large and medium-sized boulders were placed around the plaza according to the plan for the Longmire Plaza development. Several large Douglas firs on the grounds of the residences were cut down because they were damaged or hazardous to residents. [88]

Davidson's estimate for the November 1929 planting called for 112 evergreen trees two to twelve feet in height, 441 deciduous trees and shrubs one to ten feet in height, 149 small perennial plants, and a large number of ferns. Evergreen trees likely included the western hemlock, Douglas fir, western red cedar, silver fir, grand fir, and western white pine. Deciduous trees were likely red alder, Douglas maple, vine maple, bitter cherry, Sitka alder, Sitka willow, creambush, western serviceberry, red elderberry, Indian plum, Pacific ninebark, and western hazelnut. Shrubs likely included red flowering currant, black twinberry, evergreen huckleberry, salmonberry, goatsbeard, Cascades azaleas, gooseberry, salal, snowberry, and Douglas spirea. Various ferns, ground covers such as pipsissewa and bunchberry, and perennial herbs such as wood violets and twinflowers were likely planted as ground cover. [89]

Changes to the road leading past the administration building caused the removal of several cottonwoods and evergreens on the building's south side. Davidson was determined to restore the effect after the roadway was fixed because, in his opinion, they formed a natural terminus to the plaza and helped frame the new building. By 1932, a grouping of evergreens, predominantly western red cedar, were planted at this location.

For several seasons, Davidson worked individually with residents in the village for planting newly completed dwellings, where tall evergreens had been thinned to provide light and air and space for yards. He also provided the concessionaire with a plan for planting the newly constructed cabin court. Winding cobble-edged paths and understory and foundation plantings of sword ferns, salal, and other low-growing plants throughout began to give the village the unified appearance of a sylvan garden. A rock garden shaped from native boulders was planted with ferns at the entry of the administration building and small rock gardens appeared throughout the village in the yards of park staff. Davidson's work received Superintendent Tomlinson's praise and recommendation that such work be encouraged through year-to-year appropriations. [90]

|

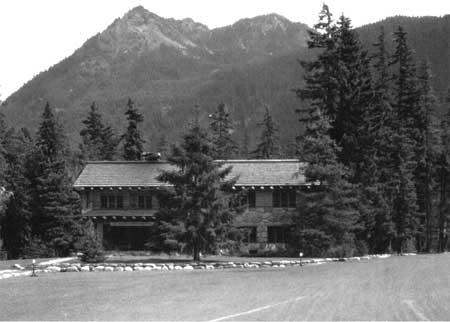

| Photographed in 1932, the "naturalized" plaza at Longmire in Mount Rainier National Park reflected the manifold achievements of the National Park Service's Landscape Division on the eve of the New Deal. Completed in 1928 and constructed of massive native boulders and stout logs, the administration building was the focal point of the village. It resulted from a synthesis of rustic design principles, including the use of native materials, pioneer building methods, and elements that stressed irregular lines and horizontality. Native firs, hemlocks, and cedars were left in place or planted around three sides and at the corners of the building Ferns and other low-growing native plants were planted in the rock-garden by the entry porch and along the foundation. A flagstone walkway and curbing comprised of horizontally-laid, lichen- and moss-covered stream boulders further unified the village setting. The plantings and rockwork represented the beginnings of a program of landscape naturalization intended to erase the scars of construction, to provide village improvements, and to blend manmade structures with a park's natural setting. (National Park Service Historic Photography Collection) |

It appears from historic photographs and the physical evidence of the hardier of plantings in the park landscape that Davidson and Sager followed Henry Hubbard's advice on planting around buildings from the Introduction to the Study of Landscape Design. Hubbard had written:

In its relation to architectural structures, planting bears its part in a landscape composition in these ways: it enframes, limiting the composition of which the structure is the dominant object and concentrating attention upon the structure; it leads up to the structure as a subordinate mass to a dominant one,—tying the structure to the ground, as the phrase goes; and it decorates, perhaps paneling the face of a structure with chosen patterns of green, perhaps changing the texture of parts of the facade from that of stone to that of leaves. [91]

Hubbard recommended that trees and shrubs be planted at the corners of buildings to create a foreground for the facade, to enframe the building with vegetation, and to make the main entrance more prominent. The shadows cast by trees placed at the corners could furthermore relieve an otherwise monotonous expanse by creating a "tracery of winter branches or the dappling of summer shade." [92]

Hubbard also urged the planting of low-growing plants in naturalistic scenes. Ground cover was an artistic medium that gave the designer an opportunity to model the ground, add interest to a particular area, or differentiate one area from another by choosing different ground-covering plants. Hubbard wrote, "A bed of ferns may grace the foot of a rock or a mat of partridge vine run over it, the darkness of a dell may be made still brighter by a carpet of blue-green myrtle, a sunny open space may be made still brighter by the yellow green of moneywort." The choice of ground cover was to depend on suitability to growing conditions and landscape character. Native ferns were an ideal material for foundation plantings and ground cover in temperate climates and moist woodland settings. They were commonly planted along the foundations of Adirondack lodges and were well-suited to the forested setting of Longmire village at Mount Rainier. [93]

Using the example of the Scarborough Bridge in Franklin Park, Hubbard stressed the compositional value of planting the areas abutting newly constructed bridges:

The span of a bridge is necessarily somewhat bounded and enframed by its abutments when it is looked at along the reach of water which it crosses, but the compositional strength of the masses on each side between which the bridge springs can be much increased by planting which rises well above the level of the bridge . . . The best outlook from the bridge is presumably up or down the stream from well out upon the bridge span, and these same plantations will give some sense of enframement to this view as well. [94]

Planting could be used to enhance architectural structures and to blend them visually into their surroundings. Park designers had certainly recognized the value of plantings as screens to hide monotonous or unpleasing surfaces, such as the power plant in Yosemite Valley. And park designers encouraged concessionaires to incorporate plantings and walks and drives into their own projects. But until 1927, it does not appear that the park designers had used planting to blend new structures to their site after construction in any routine way.

Davidson documented his work in an illustrated report in 1929, and Vint used Davidson's successful results to encourage landscape work and help justify the costs for transplanting and planting projects in other parks. Upon seeing this report, Director Albright immediately became committed to making this work a routine aspect of park construction. Albright wrote to Vint,

Mr. Davidson has kindly given me an opportunity to read his report on "Landscape Naturalization (transplanting and planting)" within the national parks. I am writing this letter to tell you that this report has made a profound impression on me and for the first time has brought me to full realization that we have not been giving enough attention to planting in the national parks. . . . I am disposed at the present time to take an unusual interest in this sort of thing and would like to take steps as soon as possible to make this so-called "naturalization" work a definite feature of National Park Service activity. [95]

The report—brief, concise, and illustrated with photographs—also established a model that would be followed in the reports of landscape architects to Vint and, later, the narrative reports for Emergency Conservation Work in both national and state parks. Davidson's work illustrated how natural vegetation could be planted in conjunction with grading the grounds of new buildings and making naturalistic improvements, such as curvilinear walkways, parking areas, and rock gardens.

Encouraged by Albright's interest, Vint asked his staff to develop cost estimates for similar work in other parks. Davidson's cost estimates for the 1929 planting at Longmire were circulated to park resident landscape architects and superintendents in fall 1929 as an example of how similar naturalization work could be included under budget requests for 1931. Vint's intention was to convince superintendents to include an item for landscape naturalization each year to improve existing conditions as well as to naturalize the sites of new construction. Because few work crews were trained in this kind of work, Vint recommended confining efforts to one or more buildings or groups of buildings, "doing a complete and finished job," that is, one that included grading, flagstone paving, and the construction of "furniture and fixtures," such as drinking fountains and stone seats. [96]

Vint's definition of landscape naturalization was:

Grading around buildings or elsewhere for better topographical effects; filling and fertilizing of soils; transplanting or planting of trees, shrubs, lawns, flowers, to make artificial work harmonize with its surroundings; erection of outdoor furniture such as stone seats, drinking fountains, flagstone walks, etc.; vista clearing and screen planting and cleanup in areas not included as Roadside Cleanup. [97]

Vint distinguished this work from roadside cleanup, which was funded under annual appropriations for roads and trails and included restoring natural conditions along highways by clearing dead timber and debris, repairing construction damage, planting slopes, screening the traces of old roads, clearing vistas, and planting old roadways and borrow pits. [98]

Under landscape naturalization, Vint grouped much of the work that had been the responsibility of park designers since Punchard's tenure, such as the clearing of vistas and campground development. Realizing, however, that landscape harmonization required much more than locating and constructing rustic structures whose design and materials blended with the natural setting of a park, he added planting and transplanting and the construction of small-scale landscape features, such as water fountains and walkways. These improvements were essential to the village concept, making the village setting more attractive and the visitor's stay more comfortable. Such improvements also enabled park designers to better manage pedestrian and motor traffic, ensure safety and sanitation, and alleviate some of the wear and tear of visitor use. Decades of increasing visitation and use were already affecting the natural character of parks. The low-budget expedients such as wooden-frame stairways and boulder-edged drives were wearing out and could no longer accommodate the increasing numbers of park visitors. Improvements in the roads and trails program had demonstrated the value of stone curbs and sturdily built trails, walkways, and guardrails. Walkways and curbing allowed park designers and managers to channel pedestrian and automobile traffic and thus minimize the wear and tear of visitor use on park resources, while guardrails ensured safety at precipitous points. The transformation of springs into pipe-fed pools and lush rock gardens ensured sanitation and provided places of appealing beauty. In short, the park designers faced the challenge of solving urban-scale problems without sacrificing natural features and scenic qualities. The program of landscape naturalization enabled park designers to create or maintain the illusion that nature had experienced little disturbance from improvements and that a stone water fountain or flagstone terrace was as much at home in a park as a stand of hemlocks or meadow of wild flowers.

Large-scale revegetation programs were instituted in several parks. One of the earliest was Rocky Mountain National Park. In 1930, Vint and Charles Peterson visited the park with ASLA representatives Gilmore Clarke and Charles W. Eliot II to examine the park boundaries and make recommendations for restoring the natural landscape in areas, such as Aspenglen, that had been heavily grazed or logged. Later that year, 1,200 three-year old western yellow pine trees were planted near the Aspenglen campground. Local hiking and conservation organizations commonly assisted in some of these early efforts. [99]

Trees were now protected during the construction of buildings; afterward they became the screens to hide development or were blended with new plantings in naturalistic groupings. Provisions were entered into the wording of contracts for the construction of buildings that required contractors to protect trees in the vicinity of their work. Not only did landscape architects confer on the location of sites for buildings, but they also identified the trees that were to be retained. This process also applied to the clearing of selected trees and vegetation in campgrounds or picnic areas. Construction scars were erased as native grasses, ferns, and shrubs embraced battered stone foundations. Tall trees were planted individually or in small clusters at the ends of bridges and corners of buildings to blend the construction with the natural setting.

Landscape naturalization revived many of the planting practices that Downing, Repton, Robinson, Hubbard, and Parsons had promoted. Several of these techniques, including the planting of climbing vines to disguise concrete and stone walls and ferns around foundations, had been favored by the Arts and Crafts movement and accompanied the use of native wood and rock as construction materials to harmonize a structure with its natural setting. Naturalistic devices such as rock gardens, fern gardens, vine-draped walls, curvilinear paths and stairs, and boulder-lined walks had been popular in the Adirondacks and had regional equivalents in California gardening.

The expanding natural history programs of the parks provided a wealth of information about the plant ecology, natural features, and native species of each park. With this information, landscape architects could readily apply Waugh's ecological approach of grouping plants, shrubs, and trees according to their associations in nature. Such work was often done informally as landscape architects and foremen on site drew materials and ideas for species composition from the surrounding woodlands and meadows. In other places, efforts were made to recreate lost plant colonies, such as wild flowers in the meadows of Yosemite. These plantings were motivated by the need to naturalize an area whose vegetation had been destroyed by construction, erosion, excessive use, or the elimination of old roads and trails. It was also motivated by the need to create an artificial screen or windbreak.

By the early 1930s, the aesthetic value of landscape naturalization was well recognized, and this kind of work became the focus of village "beautification" programs and accompanied other village improvements such as the installation of curbs, parking areas, and sidewalks and the construction of signs, lights, and water fountains. Beginning in 1933, many landscape naturalization projects were carried out with the labor and technical expertise of the Civilian Conservation Corps; this was the case with improvements carried out in Yosemite Village from 1933 to 1936.

An extensive program of naturalization occurred at Crater Lake's Rim Village, where decades of use, poor soil of ash and pumice, and harsh winter weather had contributed to the loss of natural grasses and trees. In 1930, a half-mile promenade marked by a masonry parapet wall of native rock with observation bays was constructed along the rim. Following the natural undulations of the caldera, the promenade connected the information center located in the former Kiser Studio, the Sinnott Memorial, parking areas, and the Crater Lake Lodge. Along with the walk, a fully orchestrated program of rustic and naturalistic design was planned. Experiments with native grasses were made to determine the most appropriate cover for the area before a sod mixture of wild flowers was selected. Mature trees of several native species—white fir (Abies concolor), subalpine fir (Abies lasiocarpa), noble fir (Abies nobilis), and mountain hemlocks (Tsuga mertensiana)—were transplanted from construction sites in other parts of the park. The density and arrangement of the trees followed the natural distribution and clustering found in similar areas of the park and allowed vistas of the lake from many points. The careful attention to detail even extended to the creation of water fountains imitating the crater rim in a pier of the wall and the retention of ghost trees along the slopes of the caldera. [100]

Merel Sager's program of restoration for the Rim Village was inspired by the park's primeval natural character. Sager believed that the rim area had originally had the same appearance as Sun Notch, an unspoiled and undeveloped region of the park that offered one of most attractive views of the lake. Sager wrote of Sun Notch, "Here, we find trees in abundance along the Rim, with open areas covered with grass, sedges and wild flowers. Here, in spite of sandy soil and extreme climatic conditions, nature has seen to it that beauty flourishes." Interestingly, Sager claimed this view was supported by a professor of fine arts at University of California, Wirth Ryder, and an artist of national park scenery, Gunnar Widfores, indicating the extent to which such projects were, in 1930, considered a matter of aesthetic, and not merely ecological, concern. [101]

Sager's report indicated that the work of restoration would be twofold. First, it was necessary to install walks, parking areas, curbs, and parapets to eliminate the trampling of the area by automobiles and pedestrians. Although parking restrictions imposed in 1928 had helped somewhat to remedy the situation, the soil was in such poor condition and pedestrian traffic so heavy that it was unlikely that the vegetation would recover on its own. Second, an aggressive planting project was necessary. The plan, beginning in 1930, was to recondition the soil, plant sod, and transplant evergreen trees. The trees were to be arranged in small groups to "lend variety" but not in great enough numbers to obstruct the view of the lake from the road. This planting program was to be accompanied by the installation of a system of pathways linking the parking areas and lodge with the promenade, trails, and key viewpoints.

In 1931, Congress suspended funding for capital improvements, and the work of the landscape architects was redirected to compiling development plans for the parks. It is unclear whether Albright ever approached Congress for additional funding for landscape naturalization work. What is clear, however, is that naturalization projects were funded and carried out in a number of parks that year, including Crater Lake, where the multiyear landscape restoration project got under way, and Yosemite, where meadows were cleared. The landscape naturalization program gave the landscape architects control over the many small details that could affect the scenic character of a developed area. It expanded their responsibility as protectors of the landscape to the design of the landscape itself. The program, occurring just as the park service was making major advances in park planning, set important precedents for the emergency conservation work by the Civilian Conservation Corps, which would begin in spring 1933.

PROHIBITION OF EXOTIC SEEDS AND PLANTS

In 1930, the National Park Service established a policy excluding all exotic seeds, plants, and animals from the national parks. This policy drew greater attention to the emerging program for landscape naturalization, which dealt primarily with transplanting native plants, shrubs, and trees from one location in a park to another. In November 1930, Albright issued a "set of ideals" for the use of native flora and the elimination of exotics already planted around hotels, lodges, and private dwellings. Harold C. Bryant, assistant director for education, had prepared these ideals after consulting with Thomas Vint, chief landscape architect, and the park superintendents. [102]

This policy was by no means sudden or unprecedented. Many park superintendents already had set forth similar rules for concessionaires and park residents. Joseph Grinnell and Tracy Storer of the University of California, Berkeley, had called for the elimination of exotic plants and animals from the national parks in an article in Science in 1916. In 1921, the American Association for the Advancement of Science had issued a resolution strongly opposing the introduction of nonnative plants and animals into the national parks and all other unessential interference with natural conditions. The association presented this resolution at the Second National Conference on State Parks in May 1922, urging the National Park Service to prohibit such introductions and interferences on the basis that one of its primary duties was to pass on to future generations natural areas where native flora and fauna might be found undisturbed. Planting nonnative trees, shrubs, or other plants, stocking waters with nonnative fish, and liberating nonnative game animals impaired or destroyed the natural conditions and native wilderness of the parks. [103]

The set of ideals offered the first servicewide guidelines for the management of vegetation. It was of particular importance to the work of both the Landscape Division and the Educational Division. Bryant's statement excluding all exotic seeds, plants, animals, and insects and strongly emphasizing the use of native plants in all landscape work was motivated by the serious ecological damage done by introduced species in various parts of the world. He described how "escaped" plants, such as Europe's St.-John's wort, had harmed the landscape and hindered sheep raising in Australia, how the uncontrolled growth of lantana in the tropical jungles of the South Pacific had made many areas impenetrable, and how the introduction of the American prickly pear to Australia had made large areas useless for cattle grazing and resulted in a quarantine between North and South Australia. [104]

|

SET OF IDEALS It is the consensus of opinion that national parks should stress the protection and conservation of native plants and animals, and . . . the introduction of exotic species endangers the native forms through competition and destroys the normal flora and fauna, and . . . it is the duty of the National Park Service to protect nature unchanged for the benefit of this and future generations. . . . 1. It is important that a serious attempt be made to exclude all exotic seeds and plants from the national parks and monuments. Concessionaires and residents are asked to cooperate in following carefully this endeavor to hold closely to a fundamental national park principle. (Grass seed for lawns will have to be an exception to the rule.) All concerned should avoid looking at this plan as a curtailment of personal liberty. Rather should it be regarded as an opportunity to make a garden which is unique and more difficult, therefore indicative of real achievement, certainly one more fitted to park ideals. 2. Constant endeavor should be made to eliminate exotics already planted around hotels, lodges, and private dwellings, and energy directed to the replacement of these with native shrubs and flowers. (The Landscape Division will cooperate in every way with suggestions as to the most suitable plants for replacements.) 3. As far as is possible, the same ruling shall apply to all forms of life: birds, animals, reptiles, insects. In the case of fish planted, efforts should be made to allocate exotic species (Loch Leven, Eastern Brook, etc.) to certain restricted localities. Wider planting of native species should be encouraged, with the hope that eventually non-native forms may be largely eliminated. — Harold C. Bryant, |

Grasses were not prohibited because, by 1930, the parks had little control over the many exotic species that already existed. At Yosemite, numerous exotic grass species had entered the park through the feed for the horses used in patrolling the park and in construction work. Furthermore, the artificial moisture conditions created by road construction and banking, made it necessary to use nonnative grasses for stabilizing slopes in some cases.

In formulating the statement of ideals, Bryant requested the opinions of park superintendents on the issue of exotics in the parks, an issue raised by Yosemite's Superintendent C. G. Thomson. Speaking from his experience at Mount Rainier, Superintendent Tomlinson replied,

There is a fundamental national park principle involved in this question, and it is my opinion that it is mandatory for the National Park Service to prohibit, or at least greatly restrict the planting of exotics of all kinds in the national parks if we are to pass them on to future generations in an unmodified condition. I do not see how the Service can very well permit the introduction of exotics without infringing on a vital park policy. . . . With proper care and the expert assistance of the Landscape Division, I believe there will be no great difficulty in properly beautifying residences, camps, hotels, and other "modified" areas by planting and transplanting native flowers and shrubs. [105]

Vint supported Bryant's statement but was concerned with the reaction of park residents to the prohibition. He wrote,

In order to help sell the idea it might be well to point out in the memorandum the advantages of having a garden of native plants rather than one of exotics. In a way it is an opportunity that few people get in their efforts at building a garden for personal enjoyment. It is a more difficult task than making a garden of commercial bulbs and flowers, yet when it is done is afar greater achievement. . . . Not many park employees look at this problem in that light. They look at it as an restriction of their personal liberties rather than as an opportunity to do something that cannot be done outside. I think it might be well to add a paragraph or so to your memorandum expounding the advantages of a native garden over an exotic one. Otherwise I think it is perfectly satisfactory and not a bit too strong. [106]

The prohibition on introducing exotic species into the parks was upheld by a 1932 study on what policies Congress expected would govern the National Parks based on the 1916 enabling legislation, stating that proper administration will retain these areas in their natural condition sparing them the vandalism of improvement" and "exotic animal or plant life should not be introduced." This policy would become one of the basic guidelines for Emergency Conservation Work in the national parks. [107]

Continued >>>

Top

Top

Last Modified: Mon, Oct 31, 2002 10:00:00 pm PDT

http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/mcclelland/mcclelland4d.htm

![]()