|

BADLANDS National Park |

|

Secondary Features

At some stage after the badlands rocks had been laid down, the upper exposed part was subjected to drying and, as a result, a series of nearly vertical cracks or fissures developed. Later, percolating ground water dissolved silica from the surrounding rocks and deposited it in these fissures. The most common mineral thus produced was chalcedony—a hard, brittle, waxy, bluish-tinged substance that strongly resists erosion. The soft surface rocks have been worn away and the hard, thin, knifelike ridges (dikes) stand out in sharp relief. In some places they can be traced for considerable distances. Some of the fissures were filled with softer material of contrasting color, such as brown silt or white volcanic ash. Where the filling is softer than the enclosing rock, erosion often produces a slight trough along the line of the dike.

In places, very thin cracks have been filled with chalcedony, which has later weathered out in thin, flat fragments. Indians often worked one edge of these flintlike natural blades into cutting tools, which have become known as "badlands knives" because they are found only in this region.

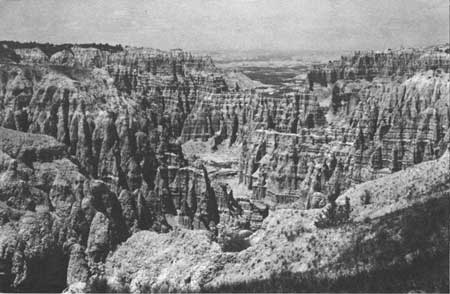

Erosion carves the badlands and then destroys them |

At certain levels in the badlands rocks, small, roughly spherical cavities developed, probably as a result of dissolving away of materials. Later, percolating ground waters lined these cavities with chalcedony. In many instances, silica crystals (quartz) grew inward from the cavity walls, sometimes completely filling them. These spherical nodules are called geodes. In some parts of the United States they occur in sizes as large as a basketball or even larger. Badlands geodes are quite small—about the size of a lemon. Since the silica is relatively resistant, the geodes wash out of the soft clays and tumble to the base of the cliffs—in considerable numbers.

Sometimes the quartz crystals do not completely fill the geodes and, occasionally, a crystal becomes detached and is loose within the cavity. When such a geode is shaken, a harsh, rattling sound is heard—hence the name rattlerock.

|

|

| NPS History | History & Culture | National Park Service | Contact |

|

Last Modified: Sat, Nov 4 2006 10:00:00 pm PST |