|

SAGUARO National Park |

|

desert plants (continued)

Non-Succulents

For the diversity of devices for adaptation to an inhospitable environment, the many species making up the non-succulent desert vegetation provide an absorbing field for study. As we have seen, there are two ways to survive the harsh desert climate; one is to avoid the periods of excessive heat and drought ("escapers"); the other is to adopt various protective devices ("evaders" and "resisters"). Short-lived plants follow the first method; perennials, the second.

Perennials

Chief among the requirements for year-round survival in the desert is a plant's ability to control transpiration and thus maintain a balance between water loss and water supply. In this struggle, the hours of darkness are a great aid because in the cool of the night the air is unable to take up as much moisture as it does under the influence of the sun's evaporating heat. Therefore, less exhaling and evaporating of water occurs from plants, and both the rate and the amount of water loss are reduced. This reduction in transpiration at night allows the plants to recover from the severe drying effects of the day. One biologist may have been close to the truth when he stated, "If the celestial machinery should break down so that just one night were omitted in the midst of a dry season, it would spell the doom of half the nonsucculent plants in the desert."

One of the common trees in the desert part of the monument is the MESQUITE (mess-KEET). In general appearance it resembles a small, spiny apple or peach tree with finely divided leaves. Its roots sometimes penetrate to a depth of 40 or more feet, thus securing moisture at the deeper, cooler soil levels, from a supply that remains nearly constant throughout the year. This enables the tree to expose a rather large expanse of leaf surface without losing more water than it can replace. A number of mechanical devices help the tree reduce its water loss during the driest part of the day (10 a.m., to 4 p.m.). Among these are its ability to fold its leaves and close the stomata (breathing pores), thereby greatly reducing the surface area exposed to exhaling and evaporating influences. In April and May, mesquite trees are covered with pale-yellow, catkinlike flowers which attract swarms of insects. These flowers develop to stringbeanlike pods rich in sugar and important as food for deer and other animals. In earlier days, the mesquite was also a valuable source of food and firewood for Indians and pioneers.

Mesquite in bloom. (Photo by Harold T. Coss, Jr.) |

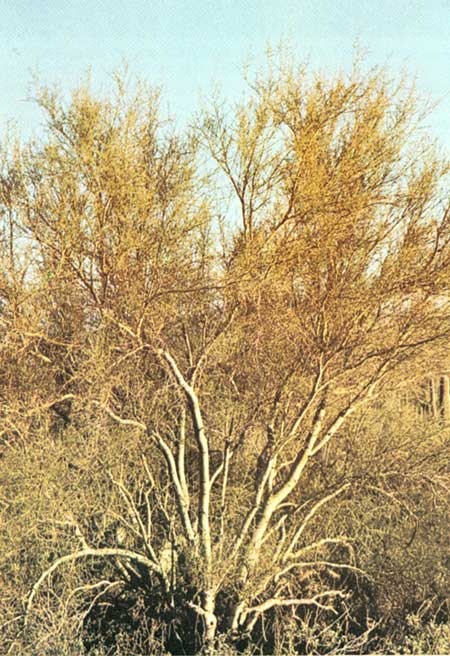

Another desert tree abundant in the monument is the YELLOW PALOVERDE. It is somewhat similar in size and general shape to the mesquite. Lacking the deeply penetrating root system of the mesquite, the paloverde (Spanish word meaning "green stick") has no dependable moisture source; but it has made unusual adaptations that enable it to retain as much as possible of the water collected by its roots. In early spring the tree leafs out in dense foliage, which is followed closely by a blanket of yellow blossoms. At this season the paloverdes provide one of the most spectacular displays of the desert, particularly along washes, where they grow especially well. Blue paloverde, growing in the arroyos, blooms well every year. Yellow, or foothill, paloverde, a separate species, blooms only if the soil moisture is high following winter rains.

Yellow paloverde, Tucson Mountain Section. (Photo by Fred E. Mang, Jr.) |

With the coming of the hot, drying weather of late spring, the trees need to reduce their moisture losses. They gradually drop their leaves until, by early summer, each tree has become practically bare. The trees do not enter a period of dormancy, but are able to remain active because their green bark contains chlorophyll. Thus, the bark takes over some of the food-manufacturing function normally performed by leaves, but without the high rate of water loss.

Carrying the drought-evasion habits of the paloverde a step further, the OCOTILLO (oh-koh-TEE-yoh) comes into full leaf following each rainy spell during the warmer months. During the intervening dry periods it sheds its foliage. The ocotillo, a common and conspicuous desert dweller, is a shrub of striking appearance, with thorny, whiplike, unbranching stems 8 to 12 feet long growing upward in a funnel-shaped cluster. In spring, showy scarlet flower clusters appear at the tips of the stems, making each plant a glowing splash of color.

A number of desert shrubs fail to display as much ingenuity as the paloverde. Some of these evade the dry season simply by going into a state of dormancy. The WOLFBERRY bursts into full leaf soon after the first winter rains and blossoms as early as January. Its small, tomato-red, juicy fruits are sought by birds, which also find protective cover for their nests and for overnight perches in the stiff, thorny shrubs. In the past, the berrylike fruits were important to the Indians, who ate them raw or made them into a sauce.

Commonest of the conspicuous desert non-succulent shrubs is the wispy-looking but tough CREOSOTEBUSH, found principally on poor soils and on the desert flats between mountain ranges. It is also sprinkled throughout the paloverde-saguaro community in the monument. A new crop of wax-coated, musty-smelling leaves, giving the plant the local (but mistaken) name "grease-wood," appears as early as January. The leaves are followed by a profuse blooming of small yellow flowers and cottony seed balls. During abnormally moist summers or in damp locations, the leaves and flowers persist the year round; but usually the coming of dry weather brings an end to the blossoming period. If the dry spell is exceptionally long, the leaves turn brown, and the plants remain dormant until awakened by the next winter's rainfall. Pima Indians formerly gathered a resinous material, known as lac, which accumulates on the bark of its branches, and used it to mend pottery and fasten arrow points. They also steeped the leaves to obtain an antiseptic medicine. Ground squirrels commonly feed on the seeds.

A large shrub of open, sprawling growth usually found along desert washes in company with mesquite is CATCLAW. Its name refers to the small curved thorns that hide on its branches. In April and May, the small trees are covered with fragrant, pale-yellow, catkinlike flower clusters that attract swarms of insects. The seed pods were ground into meal by the Indians and eaten as mush and cakes.

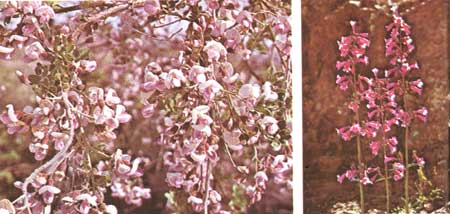

Ironwood blossoms (left). Parry's penstemon (right). (Photos by Harold T. Coss, Jr.) |

In lower elevations of the Tucson Mountain Section, the gray-blue foliage of IRONWOOD is a common sight, but the species does not range farther eastward. Its wisterialike lavender-and-white flowers blossom in May and June. The nutritious seeds are harvested by rodents and formerly were parched and eaten by Indians. The wood is so dense that it sinks in water; Indians used it for making arrowheads and tool handles.

Ferns—commonly, plants of dank woods and other moist habitats—seem entirely out of place in the desert; nevertheless, some members of the fern family have overcome drought conditions. The GOLDFERN is common on rocky ledges, where it persists by means of special drought-resistant cells.

Among the smaller perennials are many that add to spring flower displays when conditions of moisture and temperature are favorable. Perennials do not need to mature their seeds before the coming of summer as do the ephemerals; a majority start blossoming somewhat later in the spring, and gaily flaunt their flowers long after the annuals have faded and died. When the heat and drought of early summer begin to bear down, they gradually die back, surviving the "long dry" by their persistent roots and larger stems. One of the most noticeable and beautiful of this group of small perennials fairly common in the monument is PARRY'S PENSTEMON. It occurs in scattered clumps on well-drained slopes along the base of Tanque Verde Ridge. The showy rose-magenta flowers and the glossy-green leaves arise from erect stems that may grow 4 feet tall in favorable seasons.

Among the first of the shrubby perennials to cover the rocky hillsides with a blanket of winter and springtime bloom is the BRITTLEBUSH. Masses of yellow sunflowerlike blossoms are borne on long stems that exude a gum which was chewed by the Indians and was also burned as incense in early mission churches.

A conspicuous perennial that survives the dry season as an underground bulb is BLUEDICKS. Although it doesn't occur in massed bloom, it does add spots of color to the desert scene. Usually appearing from February to May, bluedicks has violet flower clusters on long, slender, erect stems. The bulbs were dug and eaten by Pima and Papago Indians.

Although neither conspicuous nor attractive, the common TRIANGLE BURSAGE is an important part of the paloverde-saguaro community in the Tucson Mountains. A low, rounded, white-barked shrub, bursage has small, colorless flowers without petals. (Being wind-pollinated, the flowers do not need to attract insects.)

One of the handsome shrubs abundant in the high desert along the base of Tanque Verde Ridge is the JOJOBA (ho-HOH-bah), or deernut. Its thick, leathery, evergreen leaves are especially noticeable in winter and furnish excellent browse for deer. The flowers are small and yellowish, but the nutlike fruits are large and edible, although bitter. They were eaten raw or parched by the Indians, and were pulverized by early-day settlers for use as a coffee substitute.

Among the attractive flowering shrubs are the INDIGOBUSHES, of which there are several species adapted to the desert environment. The local, low-growing indigobushes are especially ornamental when covered with masses of deep-blue flowers in spring.

Another small shrub, noticeable from February to May because of its large, tassel-like pink-to-red blossoms and its fernlike leaves is FAIRY-DUSTER. Deer browse on its delicate foliage.

The PAPER FLOWER, growing in dome-shaped clumps covered with yellow flowers, sometimes blooms throughout the entire year. The petals bleach and dry and may remain on the plant weeks after the blossoms have faded.

Quick to attract attention because of their apparent lack of foliage, the JOINTFIRS, of which there are several desert species, grow in clumps of harsh, stringy, yellow-green, erect stems. The skin or outer bark of the stems performs the usual functions of leaves, which on these plants have been reduced to scales. Small, fragrant, yellow blossom clusters, appearing at the stem joints in spring, are visited by insects attracted to their nectar.

Ephemerals

Every spring, after a winter of normal rainfall, parts of the southwestern deserts are carpeted with a lush blanket of fast-growing annual herbs and wildflowers—the early spring ephemerals. The monument does not get massive displays, however, since it is lacking in the species that make the best show. But it does have many annuals that are beautiful individually or in small groups. Many of these "quickies" do not have the characteristics of desert plants; some of them, in fact, are part of the common vegetation of other climes where moisture is plentiful and summer temperatures are much less severe.

What are these "foreign" plants doing in the desert, and how do they survive? With its often frostfree winter climate and its normal December-to-March rains, the desert presents in early spring ideal growing weather for annuals that are able to compress a generation into several months. Several hundred species of plants have taken advantage of this situation.

There is WILD CARROT, which is a summer plant in South Carolina and a winter annual in California (where it is called "rattlesnake weed"). In the desert, its seeds lie dormant in the soil through the long, hot summer and the drying weather of autumn. Then, under the influence of winter rains and the soil-warming effects of early spring sunshine, they burst into rapid growth. One of a host of species, this early spring ephemeral is enabled by these favorable conditions to flower and mature its seed before the pall of summer heat and drought descends upon the desert. With their task complete, the parents wither and die. Their ripened seeds are scattered over the desert until winter rains enable them to cover the desert with another multicolored but short-lived carpet of foliage and bloom.

The one-season ephemerals do not limit themselves to the winter growing period. From July to September, local thundershowers deluge parts of the desert while other areas, not so fortunate, remain dry. Where rain has fallen, another and entirely different group of plants, called the summer ephemerals, find ideal conditions for growth and take their turn at weaving a desert carpet. Their seeds have lain dormant over winter. These summer "quickies" are plants that, farther south in Baja California and Sonora, Mexico, flourish during the winter rainy season. Saguaro National Monument is doubly fortunate in that it lies within a section of desert having not only its own year-round vegetation, but also summer wildflowers "borrowed," for winter use, from its eastern and western neighbors, and winter wildflowers for summer decorations from its southern neighbors.

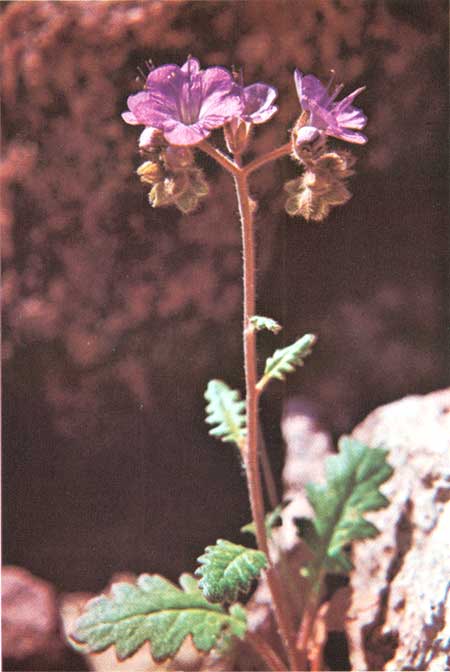

Phacelia, an ephemeral. |

The short-lived leafy plants of summer and winter are able to compress their entire active life into 6 to 12 weeks when conditions are most suitable. Thus, they can escape all the rigorous periods of the desert climate by living for 8 or 9 months in the dormant seed stage. Some of the spectacular and colorful flowers of the monument are among these ephemerals that survive desert conditions by escaping them. It must be remembered, however, that when drought conditions or abnormally cold spring weather upset the norm—a not unusual occurrence—response of ephemeral plants is greatly restricted. If suitable conditions do not develop during the season for growth of a particular kind of ephemeral, its seeds will simply wait a year or more until conditions are favorable.

How do the seeds of ephemerals "know" when it is time to germinate? Experiments have revealed that the seeds of annuals will germinate only when enough water percolates through the soil to dissolve away a "growth inhibitor" in their coats. A single light rain will not do the job. In this way premature sprouting into a too-dry environment is prevented. The winter annuals, furthermore, will only germinate when soils are cool, and the summer annuals when soils are warm. These finely tuned adaptations thus allow plantlife to take full advantage of favorable seasons in the desert.

Early spring ephemerals climax their show in March. From late February to mid-April they are completing their growth and putting forth the precious seeds that will assure survival for the next generation. At the head of this parade of flowers in the monument is a purple-blossomed immigrant from the Mediterranean, the now thoroughly naturalized FILAREE. In addition to the small purple flowers, which may appear as early as January, the conspicuous "tailed" fruits almost always attract attention. When dry, they are tightly twisted, corkscrewlike; when damp they uncoil, forcing the needle-tipped seeds into the soil.

INDIAN WHEAT is one of the first plants to lay a green carpet over the sandy desert floor in spring. The tan, individual flower heads are conspicuous, but their numerous, close-growing spikes form a thick, luxuriant, pilelike ground cover. The countless tiny seeds are eagerly sought each spring by coveys of Gambel's quail, and are also harvested by Pima and Papago Indians.

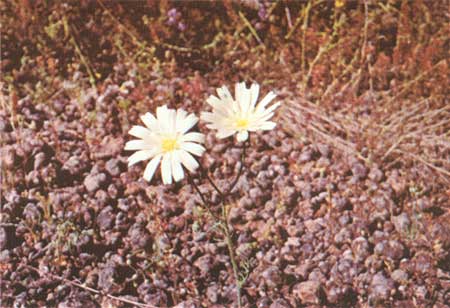

DESERT CHICORY is somewhat like the common yellow dandelion but is longer stemmed and less coarse. Its white or butter-yellow blossoms make it one of the noticeable spring annuals in the desert. It rarely grows in pure stands but appears in conspicuous clumps among other short-lived plants.

Somewhat similar in appearance to desert chicory is WHITE TACKSTEM, one of the handsomest of the spring quickies. It is usually found on dry, rocky hillsides and has white or rose-colored flowers. Its name is derived from the presence of small glands which protrude in the manner of tiny tacks partially driven into the stems.

White tackstem. (Photo by William Hoy) |

Following abnormally wet winters, FIDDLENECK covers patches of sandy or gravelly soil with a dense growth of bristly erect plants. These bear tight clusters of small yellow-orange blossoms arranged along a curling flower stem resembling the scroll end of a violin, hence the name. This plant, favored by the same growing conditions as creosotebush, frequently forms a dense though short-lived growth around the bases of those shrubs.

Associated with fiddleneck and creosotebush, SCORPIONWEED adds its violet-purple blooms to the spring flower display following winters of above-normal precipitation. The name is derived from the curling habit of the blossom heads, which may remind the observer of the flexed tail of a scorpion. Touching the plant may cause skin irritation in susceptible individuals. Unfortunately, scorpionweed is also widely known as wildheliotrope, thus contributing to the confusion engendered by duplication of popular names. The plant properly called WILD-HELIOTROPE is similar in general appearance, but the flowers are white to pale purple and their odor is more pleasing than that of the scorpionweed. Wild-heliotrope, or "quailplant," is another of the early spring ephemerals, but under favorable conditions, where soils are moist, it may continue to live and bloom throughout the year.

Growing in sandy locations and quite noticeable because of its large, yellow, showy, long-stemmed flower heads, the DESERT-MARIGOLD helps to open the spring blossoming season. Where moisture conditions are favorable, these plants may continue to bloom throughout the summer and well into autumn. Sometimes, during the hottest, driest time of the year, desert-marigolds are among the very few blossoms brightening the desert floor. Their bleached, papery petals persist for days after the flowers have faded, giving the plant the name paper-daisy.

Desert-marigold. |

One of the few species that makes a carpet of color in the monument is the tiny BLADDER-POD. This low-growing annual of the mustard family begins to cover open stretches of desert with a yellow blanket in late February or early March following wet winters. Bladder-pod is usually found in pure stands surrounding islands of cholla, creosotebush, and paloverde. It also mingles with other spring ephemerals, where it is promptly submerged by the ranker, taller-growing, more conspicuous annuals.

Illustrating one of the interesting phases in evolutionary variations among plants, the LUPINES are represented by several species which are able to survive and prosper in the desert. Some of the lupines are annuals of the quickie type; others are perennials with a life cycle of several years. Some of these longer-lived species join the ephemerals in the spring flower show, while others are more leisurely in approaching their blossoming time.

Bladder-pod. (Photo by J. Carrico) |

|

|

| NPS History | History & Culture | National Park Service | Contact |

|

Last Modified: Sat, Nov 4 2006 10:00:00 pm PST |