|

ORGAN PIPE CACTUS National Monument |

|

Animals (continued)

Animals of the Succulent Desert

Among the commonest birds of the desert are the thrashers, of which there are several species. Since most of them are year-round residents, they breed in the desert environment, building rather shallow, loose nests of twigs, usually lined with rootlets, in mesquites, shrubs, or cholla.

The thicket-loving crissal thrashers, largest of the group, have long, curved bills. They are delightful songsters, although the song is neither loud nor varied.

Curve-billed thrashers prefer the more open upper bajadas. There they may be seen and heard among the chollas and organpipes along the bases of the mountains and in the mouths of canyons, their favorite nesting sites. Among their companion songsters are mockingbirds and house finches.

Phainopeplas are particularly noticeable in winter, when they frequent the succulent desert. Their prominent crests and the silky black plumage and white wing bars of the males arouse the curiosity of persons unfamiliar with these charming residents. During the nesting season, these birds are much less in evidence, being busy rearing young among the mesquites along the dry wash borders. Mistletoe berries are among their sources of food and moisture.

The Sonora spiny lizard prefers rocky localities or tree-grown banks of desert washes. |

Cactus wrens build globular nests in chollas and make their presence known with their harsh, unmusical songs and chatter.

Nearly everyone is familiar with that desert clown, the roadrunner, whose ruffled appearance, awkward gait, and unorthodox food habits set it apart. These peculiar birds prefer to remain on the ground and will rarely fly unless closely pursued. They forage widely among the desert plants in search of insects and spiders, reptiles, young birds and rodents, cactus fruits—almost anything edible. They usually conceal their bulky twig nests in the center of a bush or low tree in dense thickets bordering sandy washes.

Several species of birds make use of nest pockets in the pulpy stem tissues of the giant saguaros. Among these are Gila woodpeckers and gilded flickers. As secondhand homes, these pockets are in considerable demand by tiny elf owls and ferruginous owls, which use them for sleeping retreats during the day, and by sparrow hawks that raise families in them.

Although not limited to saguaro forests, the sparrow-sized elf owls, smallest of the nocturnal predators, are more numerous where the big cactuses are abundant. They depend largely upon insects for both food and moisture. During the serenity of the desert twilight, these tiny creatures are active in the vegetation, their tremulous whistling notes adding to the beauty of the night.

Building their bulky stick nests in the forks of saguaros, the desert's large winged hunters—the redtailed hawk by day and great horned owl by night—between them keep up a 24-hour patrol on the search for reptiles and small mammals. The owl is a major influence in controlling skunk populations, the big night hunters seeming to be unaffected by the odorous musk.

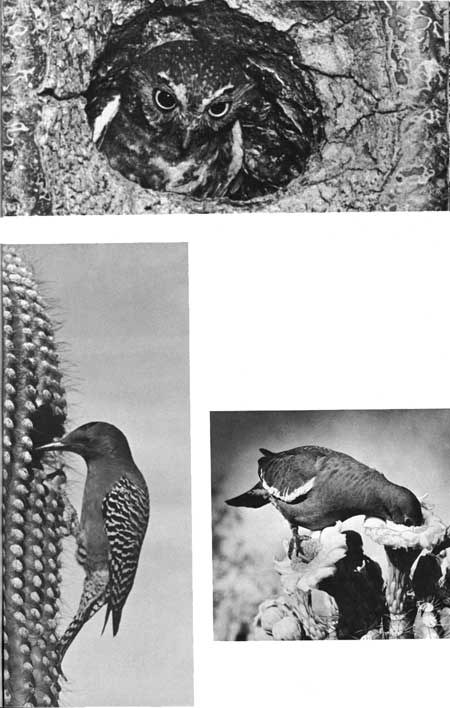

The saguaro cactus plays an important role in the lives of several species of birds. Gila woodpeckers (lower left) drill nest holes in the trunks. Elf owls (above) often sleep during the day in abandoned woodpecker holes. Whitewinged doves (below) obtain nectar from the blossoms and feed on the ripe fruits. Building conspicuous stick nests in forks of the branches, red-tailed hawks and horned owls are among other birds that take advantage of the saguaro's hospitality. |

Because they live only where they can find water, skunks are not found in many parts of the desert. Where water is available, several species, including the common striped skunk, may be present. Both the hog-nosed skunk and the hooded skunk occur along the Mexican border. The small spotted skunk prefers rocky hillsides, and it is rarely encountered on the open desert. Hunting at night, skunks are seldom seen by monument visitors, although they occasionally disturb campers. Their food consists of insects, mice and other small rodents, reptiles, bird eggs, and cactus fruits.

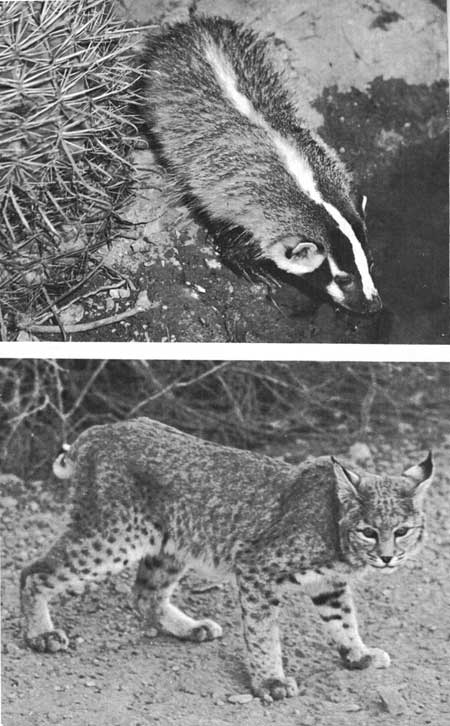

The badger, a close relative of the skunk, is occasionally seen, but its presence in the desert is usually revealed by fresh piles of earth at the entrance to holes, about 1 foot in diameter, which it digs when seeking rodents, its principal food.

Since many of the small animals of the succulent desert are abroad only at night, the uninformed visitor may be disappointed because he failed to see any during a drive through the monument. This lack is especially noticeable during hot weather, when even those mammals which are normally active during the day seek shade or remain underground, where lower temperatures and slightly higher humidity reduce the animals' loss of precious moisture.

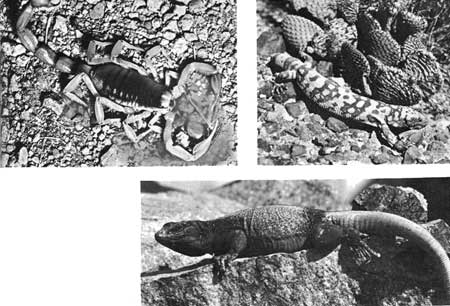

Several species of scorpions may be encountered hunting at night or hiding during daylight hours beneath a rock, under the bark of trees, or even inside houses. The majority are not dangerous although they can inflict painful stings. Stings of two small species may be fatal to children 4 years old or younger, and so great care should be exercised to protect cribs and playpens from invasion by scorpions.

Some of the nocturnal creatures, such as the white-throated woodrat, leave ample evidence of their presence although they remain under cover during the day. Woodrats, sometimes called packrats or traderats, build piles of desert debris, especially cactus joints, which are often seen among rocks or in cholla thickets. Within these armored mounds, the rats maintain intricate tunnels and runways and raise their young in well-protected nests. The cone-nose, a parasitic insect which infests woodrat nests, sometimes during May and June invades human habitations and may inflict an unpleasant and sometimes serious bite.

Active among stands of dead chollas, roots, and other wood materials, the so-called white ants, or termites, live in small underground colonies. When they invade woody material above ground, they build earthen travel tubes and cover the sites of their activities with a plastering of mud, for it is their habit to work in darkness. The presence of earth-plastered stems of dead chollas may attract your attention to the activities of these insects.

(Above) Badgers hunt the hard way, digging their prey from underground burrows. (Below) Bobcats are night prowlers, but they are sometimes seen in early morning and late evening. |

Visitors to the monument who have the time and equipment to use some of the less-traveled roads, and who can be in the extensive back country in the early morning or around sunset in winter, may expect to see some of the larger mammals. Among these, the mule deer finds browse shrubs on the succulent desert bajadas, along the desert washes, and among the rocks of the foothill slopes and canyon mouths. During the hot part of the year, deer may be found among the oak thickets on the slopes and upper canyons of the Ajo and Growler Mountains.

The gray fox is generally nocturnal in its habits. It roams widely throughout the desert and over the mountain slopes. It is probably the most abundant and widespread of the monument's canine predators and is not infrequently seen by visitors in the beams from their automobile headlights. The diet of these attractive animals consists of woodrats, mice, rabbits, and other small creatures, including an occasional snake, lizard, or bird. Gray foxes sometimes retreat during the heat of the day into the lower branches of a mesquite or paloverde tree.

Coyotes are roamers and cover a great deal of desert in their search for food. Their diet consists of rodents and other small animals and also considerable vegetable matter. Coyotes are also found throughout the mountainous parts of the monument wherever food is present. Although they are abroad at all times, they are usually seen and frequently heard during the hours around sunrise and sunset. You may be fortunate enough to see one at almost any time or place in the monument.

Bobcats are sometimes seen along desert washes and among the cactuses on the bajadas, but they prefer the rough and rocky terrain of the hills, mesas, and mountain canyons. They are active both day and night but are most often seen at dusk. They capture birds, desert rodents, rabbits, and other small animals for food.

Among the many species of lizards and snakes that inhabit the succulent desert, two perhaps are of general interest—the western diamondback rattlesnake and the Gila monster. The diamondback is the poisonous snake which may possibly be encountered, although the chance of seeing one is slight. During summer, these reptiles remain quiet throughout the day, coming out to hunt at night. Persons having occasion to walk in the desert at night should use a flashlight to avoid coming upon a rattler unawares. Climbers should always look before placing a hand on a rock or ledge. These snakes are alert and will often assume a defensive coil when approached. Their principal food consists of rabbits and small rodents; occasionally they catch a bird.

These desert creatures have varied means of defense. The desert hairy scorpion (upper left) can inflict a painful but not dangerous (to humans) sting. The large black-and-coral gila monster (upper right) has a poisonous bite. Sinister-looking but harmless, the chuckwalla (below) wedges itself in a rock crevice when threatened. |

The Gila monster, the only species of poisonous lizard found in the United States, is sometimes met as it ambles across the desert floor. These large black-and-coral reptiles, which may attain a length of 2 feet, should never be teased or handled. They usually try to escape when approached, hurrying to gain the protection of a low-growing shrub or to crawl among the stems of a cactus. They are fond of eggs and will raid the nests of ground-dwelling birds. They are reported, also, to eat small rodents, nestling birds, and occasionally a smaller lizard.

|

|

| NPS History | History & Culture | National Park Service | Contact |

|

Last Modified: Sat, Nov 4 2006 10:00:00 pm PST |