![]()

MENU

SECTION I

SECTION II

History

Needs

Geography

Historic Sites

Competitors

Economic Aspects

SECTION III

Federal Lands

State and Interstate

Local

SECTION IV

Division of Responsibility

Local

State

![]() Federal

Federal

Circulation

SECTION V

Recreational Use of Land in the United States

SECTION IV

PROGRAM FOR DEVELOPMENT OF THE NATION'S RECREATIONAL RESOURCES

4. FEDERAL COMPONENTS

National Parks and Monuments

The objectives of the National Park Service include the protection of areas of Federal land having outstanding values of scenic, historic, prehistoric, or sites scientific character, and the use of these areas by the people, for inspiration, education, and recreation insofar as these uses are consistent with the preservation and protection of the areas.

The objectives of preservation for future generations and of present use are interwoven, but of two, the preservation is the more important and primary consideration. Areas may be reserved for protection, without present use, looking forward to such us in some future time. Present use that is destructive of the objects for which the reservation was made should not be permitted.

It is recognized that preservation and use may conflict. In such cases the public interest will govern, in an effort to secure a maximum of both objectives combined, without eliminating either objective.

Most of the areas administered by the National Park Service have been reserved from publicly owned lands; some have been gifts to the Government for public use.

PHOTO 14.—Spruce Tree House as seen from the porch of the new

community house at Mesa Verde National Park, Colo.

Congress has heretofore followed the policy that it is not desirable for the Federal Government to purchase privately owned lands for use as national parks or monuments, but, when a suitable area is offered as a gift, it may properly be accepted and thereafter administered by the Federal Government for the benefit of the Nation. In a number of cases Congress has appropriated funds for the purchase of private lands in established national parks and monuments. It might become desirable for the Federal Government to purchase areas of outstanding national value, either in cooperation with the States or alone. It is obvious that if the Federal Government does enter on such a purchase program, effective restrictions will have to be provided to limit the areas purchased to those which are clearly of great national value.

Beneficial types of recreation appropriate to the areas should be developed and offered to visitors. Recreation, in its broader sense, is one of the major purposes of the National Park Service, but it is inherently combined with the preservation of the outstanding values for which the areas were set aside.

Whatever the number of national parks and monuments, they should be selected in accordance with existing policies as indicated by previous congressional and administrative action, in order that the areas should be those of outstanding national importance.

It is the responsibility of the National Park Service to evaluate these various proposed areas in comparison with the existing established areas. Areas of Federal lands of outstanding national value should be preserved before they pass into private ownership or before the exceptional features of the areas are destroyed. Areas of secondary importance, not truly of national value, should not be established as national parks or monuments, for inclusion of such areas would dilute the value of the system and open the way for additional sub-standard areas, so that, if not carefully guarded, the time would come when a national park or monument would lose its significance as indicating an area of outstanding national value. Any existing national parks monuments that do not meet standard requirements should be eliminated from the system.

PHOTO 15.—Mount Seattle from the east.

Elimination, Extension, and Addition of National and Monuments.—The system of national parks and monuments is intended to comprise the outstanding areas of their respective types.

In order that the intention may be fulfilled, it is necessary—

1. To eliminate from the system areas not of outstanding national value.

2. To add to the system the areas of greatest national value.

The principal objective of General Grant National Park is to protect the giant Sequoias within its boundaries. This park is located not far from Sequoia National Park, the primary objective of which is also the protection of the Sequoias. It would seem desirable that these two areas should be combined under one national park designation and administered as a unit.

It is suggested that Zion and Bryce Canyon National Parks and Cedar Breaks National Monument be combined and administered as a single national park, consisting of three detached areas.

Grand Canyon National Monument should be added to Grand Canyon National Park, since it is adjacent to the larger reservation and is of similar type.

Death Valley National Monument is believed to be suitable for establishment as a national park.

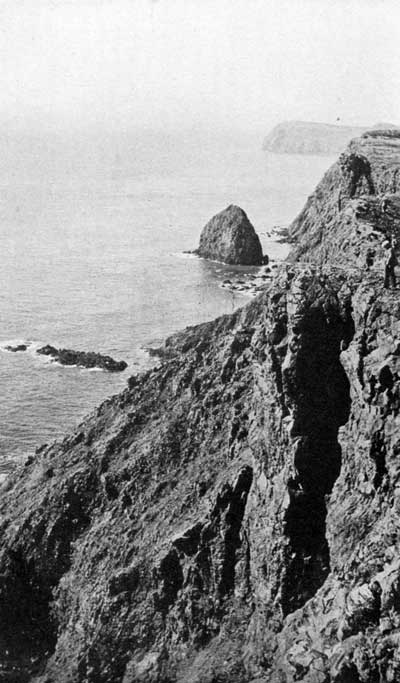

PHOTO 16.—The head of the Queets from the Queets-Quinault Divide.

Additions to Existing National Parks and Monuments.—In a program of enlarged and extended Federal activities in forestry, recreation, and wildlife administration, it will be desirable to enlarge greatly the national forests and also the national park system. The enlargement of the latter may be accomplished by increasing the area of some of the present reservations and by establishing new ones.

In a number of existing national parks and monuments, public usefulness would be increased by additions to them or revision of their present boundary lines. Boundary changes may be desirable for some of the following reasons;

1. To include additional important scenic features.

2. To provide a more nearly complete biological unit for the important types of wildlife in the area. Sometimes a park or monument includes the summer range, but not the winter range, of species that it is important to protect.

3. To provide a more suitable area for administrative purposes and for the accommodation of the public.

4. To provide a protective zone around the principal feature which the area is reserved to protect.

5. To permit the construction and maintenance of approach roads.

6. To facilitate administration by substituting topographic boundaries for land-line boundaries.

As a basis for determining the classification of areas as between national park and national forest categories, a comparative statement of the functions and objectives of national parks and national forests is included here:

National Forests.—The Department of Agriculture has defined the objectives and functions of national forests as follows:

The National Forests are primarily utilitarian in purpose. Their dominant function is to preserve and perpetuate the timber supply and to safeguard the watersheds of streams. Their resources are to be employed to meet the economic requirements of the Nation, to the fullest degree consistent with their adequate perpetuation. In pursuance of this principle, the cutting of timber, the utilization of forage, the storage of water for irrigation or power, the occupancy of lands for purposes of industry, commerce, or residence, and the exploitation of their mineral resources is permitted under proper regulation and control.

But the very existence of forests, streams, varied and abundant vegetative growths, fish, game animals, etc., in combination with a wide and varied range of topographic and climatic conditions operates to create within the national forests an integrated recreational resource, which, when properly coordinated with the industrial utilization of other resources, has a tremendous social and economic significance, that within limited areas may be of paramount importance and demand specialized and intensive development and management. The dedication of such areas to popular mass recreation is in no way inconsistent with the primary purposes for which the national forests were created but, to the contrary, is in complete accord with the principles of regulated use by which their administration is governed * * *

The definition of the objectives and functions of the national forests as given by the Department of Agriculture seems entirely acceptable in principle. The only place where differences of opinion might arise lies in the degree to which the Forest Service, in response to the demands of popular recreation, might depart from what is termed its primary economic function and set up a specialized and intensive development and management which would duplicate that already maintained by and pertinent to the National Park Service.

National Parks and Monuments.—National parks are the superlative natural areas, set aside and conserved unimpaired for the benefit and enjoyment of the people. Their development shall be conducive to the realization of the scientific and recreational values consistent with their inherent characteristics.

National monuments are the outstanding areas or objects of prehistoric, historic, or scientific value, set aside and conserved unimpaired because of their national interest.

(Other classified areas, such as national historical parks, national military parks, national cemeteries, etc., are administered by the National Park Service. Since, however, these types of areas are not at present involved in the problem of differentiating between national forests and national parks, they are not treated specifically in this statement.)

It is believed all areas of national park or monument quality—Kings Canyon, for example—should be included in the national park system and administered by the one agency of Government created to conserve them unimpaired for the benefit and enjoyment of the people. Areas of national park or monument character should not be jeopardized by concurrent commercial use.

National parkways, which are for recreational and not for commercial purposes, should be accorded similar protection and administration.

The act to establish a National Park Service states:

The Service thus established shall promote and regulate the use of the Federal areas known as national parks, monuments, and reservations hereinafter specified by such means and measures as conform to the fundamental purpose of the said parks, monuments, and reservations, which purpose is to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wildlife therein and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations.

PHOTO 17.—The Blue glacier, showing deep crevasses.

Recreation.—It is assumed that recreation is that which re-creates the individual. This is broader than the physical activity, or playground concept of recreation. In its broader sense, recreation includes spiritual and mental stimulation and exercise as well as physical activity. It is believed that any more restricted definition of recreation is untenable.

If properly utilized, both national forests and national parks will provide recreation. To hold that either administrative service should not provide for the recreational use of these resources is futile. The types of recreation germane to the purposes of the areas that each service administers should be defined.

Since national parks are superlative natural areas, the type of recreation they provide must be consistent with their natural characteristics. To provide this type of recreation is the primary objective of national parks and there is no other competing objective. Preservation and interpretation of primeval nature and of the scientific, prehistoric, and historic objects is an integral part of the main objective.

Since the national forests are primarily utilitarian in purpose, the type of recreation which they provide is therefore incidental and must be consistent with all other uses of the forest and must be correlated with them.

If the recreational values of a superlative area to be realized, the area must be dedicated to that alone. Otherwise it will be impaired. You cannot conduct banking in a temple and keep it a place of worship. Neither can you graze sheep and cattle and cut trees in a superlative forest and keep the forest superlative.

All such areas, then, if they are to be conserved unimpaired for the benefit and enjoyment of the people, should be dedicated to that purpose alone. And it is submitted that such areas should be classified as national parks and monuments, to be administered according to the standards for such areas.

It is evident that administration of great scenic areas, for appropriate recreational use, under two departments of Government is an unwarranted duplication of expenditure and effort. Moreover, the administration of national parks and monuments by the Forest Service would be inconsistent with the purposes for which it was created; just as the administration of national forests by the National Park Service would be a similar inconsistency.

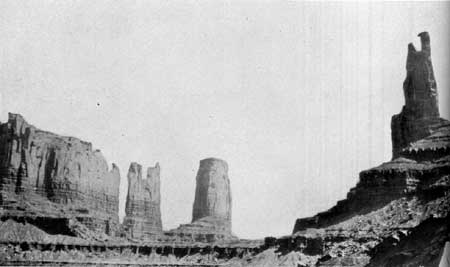

PHOTO 18.—Monument Valley on the Navajo Reservation, Ariz.

Boundary Adjustments.—The unit idea is the premise upon which boundary adjustments are advocated. That is, if a superlative natural area is to be preserved, it must be a unit capable of sustaining itself.

It would be futile to attempt to provide a city with pure water by controlling the area of the reservoir only. It is necessary to control the watershed above the reservoir to assure pure water within it. In like manner, it is futile to set aside a superlative area and attempt to preserve it unimpaired, without including the tributary areas which give rise to its outstanding character.

The unity of the area is particularly important to the psychological aspects of the problem. To take an obvious example: Cliff Palace in Mesa Verde National Park provides a superb and satisfying spectacle in the primitive setting of its secluded canyon. What would Cliff Palace be with an oil well stuck in front of it? It is necessary, then, in order to preserve the character of Cliff Palace to establish a suitable, protected area around it. Moreover, the archeological story of Cliff Palace adds to the pleasurable experience of the visitor. To preserve the primitive environment which made possible the life of the cliff dwellers on that arid mesa makes appreciation of the whole picture more vivid. Finally, there is the important matter of approach to the Cliff Palace area. This must be handled as part of the unit, for there are subtle values involved. These may seem to be intangible considerations but we acknowledge them frankly, and deal with them practically, in every city when we establish business and residential zones.

Perhaps in no instance is the unit character of an area more clearly exemplified than in the attempt to preserve its native biota. A park such as Yellowstone is established. Animal life and the vegetative cover are absolutely essential to the character of the area. But the winter game ranges are excluded. Civilization occupies them. The available range within the park is overgrazed; forest reproduction is consumed; the ground is laid bare and erosion occurs. The superlative features of the area are impaired because the foundations upon which they rest were not included.

Zion Canyon was set aside as a national park. The canyon itself is the superlative feature. But the watershed above the canyon is overgrazed. Run-off is violent. The wooded floor of Zion Canyon is washing away with repeated floods. Again, the unit character of the area has been ignored.

The development of a park is of vital importance in its utilization and preservation. Human utilization of such areas, in a manner consistent with their characteristics, imposes extremely complex problems. If the reserved area is too small or is improperly conceived and delineated, the necessary developments and accommodations must impinge more severely upon features which it was desired to save. This is particularly true of national monuments, such as Aztec Ruins, Casa Grande, Bandelier, Muir Woods, and Devils Tower, as well as of most of the national parks. Human and wildlife utilization of an area is of necessity more concentrated and destructive in a restricted area than in a spacious one. The development and utilization of a park are inescapable elements in the problem of its protection. They must be considered in delineating its boundaries.

Unless a park is treated as a unit it will be impaired. This applies equally to its spiritual aspects, its scientific, aesthetic, and historical values, its forests and wildlife, its development, human utilization, protection, and administration.

PHOTO 19.—Meteor Crater, Ariz. The pit caused by the impact of a

meteor with the earth. The crater is 570 feet deep and 4,000 feet in

diameter.

Commercial Considerations.—At times, there seems to be a tendency to assume that only areas of little or no commercial value should be set aside as national parks, or utilized for recreation. If this premise were generally accepted, there would be no superlative areas saved for there is not one such area which does not have potential economic value apart from its utilization for recreation. No one could deny that the coast redwoods of California and the virgin forests of the Olympic Peninsula would have economic value if cut for timber. But it is these merchantable trees which make the area superlative. This Nation can afford to reserve samples of its heritage for present and future enjoyment. And then, of course, there is the economic proposition that some of these same trees would be worth far more to look at than to chop down.

New Areas.—Aside from the Yellowstone, which was established when the area was in primeval condition, there never would have been another national park if the areas had been refused because of previous commercial exploitations. For instance, it was necessary to accept Grand Canyon, Zion, Bryce Canyon, Mesa Verde, Glacier, and others, with privately owned property and certain lifetime grazing permits in order to establish these parks at all. But the private holdings gradually are being eliminated and the grazing is decreasing as the permits expire.

Because civilization has moved into the choicest areas faster than they could be established as national parks, some parks now must be carved out of commercialized areas. To permit a previously established and temporary commercial venture to thwart the establishment of national parks now would mean the loss of almost all remaining areas of national park quality.

It is realized the attempt to preserve superlative areas is a highly specialized form of conservation, the benefits of which are not always apparent. It is a type of present use which will not limit the possibilities of future use. The Government is reserving certain archeological areas which will not be excavated for many years, with the belief that archeological knowledge and technique in the future will discover values which present methods of excavation would discard by the shovelful. In like manner, we should not "excavate." our great wilderness areas too heavily at present. For the health of man and of vigorous scientific inquiry, there is need of large superlative areas where nature can be enjoyed and studied as it was in the days of Audubon and Darwin. Thus, we try to leave the doors open to new social values and new scientific knowledge.

The following areas are among those previously under consideration, and it is recommended, in view of the proposed extension of Federal activities in both national forests and national parks, that these areas be studied again to determine how the public interest would be served best.

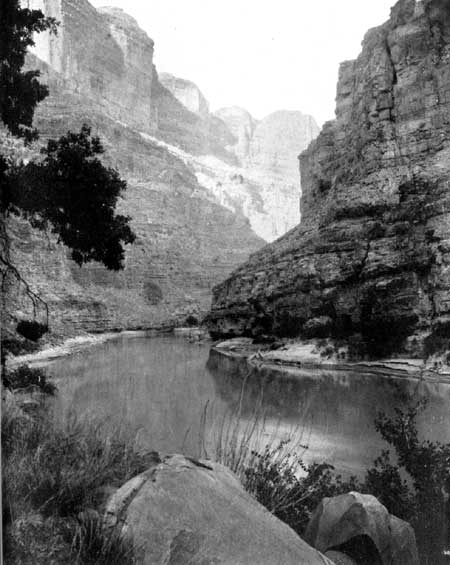

PHOTO 20.—Southeastern Utah. Cataract Canyon on the Colorado River

below the mouth of the Green River.

Additions involving lands now under the administration of the Forest Service:

1. Mount Olympus National Monument.—The present area of this national monument is approximately 300,000 acres, or about half of the original area set aside by proclamation of Theodore Roosevelt in 1909. The present boundaries should be revised in order to include the winter range of the Roosevelt elk and a large representative section of the finest forest west of Mount Olympus which is of a type not duplicated elsewhere in the United States. This exceptional forest is in an area of high rainfall, the total annual precipitation being 140 inches or more. These lands are now in the Olympic National Forest but, as indicated above, some of them were in the Olympic National Monument as originally established. The Olympic Mountains constitute one of the most primitive and untouched areas of beautiful mountain scenery in the United States.

2. Rocky Mountain National Park.—Inclusion of Arapaho Park country.

3. Yosemite National Park.—Inclusion of approximately 9,600 acres of superlative sugar pine forest near Carl Inn, on west boundary of the park (see also, p. 28, proposed Sierra Nevada Park).

4. Sequoia and General Grant National Parks.—(a) Kings River Canyon area.; (b) Redwood Mountain area (also involves private property); (c) Mineral King area; (d) land south of General Grant National Park (see also p. 28, proposed Sierra Nevada Park).

5. Crater Lake National Park.—Diamond Lake area and other boundary adjustments.

6. Yellowstone National Park.—Thoroughfare and upper Yellowstone country

7. Grand Teton National Park (legislation recently submitted to Congress).

8. Grand Canyon National Park.—Comparatively minor extensions of both north and south boundaries.

9. Carlsbad Caverns National Park.—Addition, perhaps as a detached unit, of a wilderness area now in the Lincoln National Forest.

10. Lassen Volcanic National Park.—Boundary changes, especially to the north, are recommended for study.

The following addition that has been proposed involves land now in the public domain.

11. Zion National Park.—Kolob Canyons, Utah.

The following additions that have been proposed involve land now in private ownership:

1. Carlsbad Caverns National Park.—Guadalupe Mountains in Texas.

2. Great Smoky Mountains National Park.—Extension to the Pigeon River, on the south, in order to provide a more complete biologic unit for wildlife; also an exchange of land between the Cherokee Indian Reservation and the park.

3. Hawaii National Park.—An extension of the southern portion of the park, including additional coast line. Some other areas are suitable for addition, if available.

Areas Suitable for National Parks and Monuments.— Areas believed to contain features that qualify them for designation as national parks or monuments, and should be further studied, include the following:

1. Areas in the Navajo Indian Reservation, Arizona and Utah, and in adjacent portions of the public domain in southeastern Utah. This region includes the present Canyon de Chelly National Monument, the Navajo National Monument, comprising three detached areas of archeological value, and the remarkable Rainbow Bridge National Monument. In addition to these established national monuments there is Monument Valley, a highly scenic area with great sandstone monoliths in a desertlike country of wilderness character, primitive in condition and of appealing interest. Navajo Mountain, the sacred mountain of the Navajos, is the highest point of elevation in the region. It is a prominent landmark, and offers an extensive view over an area of great scenic interest and variety. Coal Canyon and Blue Canyon are other scenic features of the region. In Utah the San Juan River flows through a country that is unusually scenic and but little known. The Goose Necks of the San Juan are one of several remarkable geologic features.

PHOTO 21.—In southeastern Utah. Goosenecks of the San Juan River.

Canyon de Chelly National Monument was established with the approval of the Navajo Indians and of the Indian Service. If it is found to be in the interest of the Indians to establish a national park in the Navajo Reservation, under an agreement that would be mutually satisfactory, then the scenic and archeological features of the area will entitle it to consideration.

2. Palm Canyon, Riverside County, Calif., near Palm Springs, is a part of the Agua Caliente Indian Reservation. It contains the finest groves of native palm (Washingtonia filifera) in the Southwest. The approval of the Indians and of the Indian Service would be a necessary preliminary to consideration of this area for a national monument.

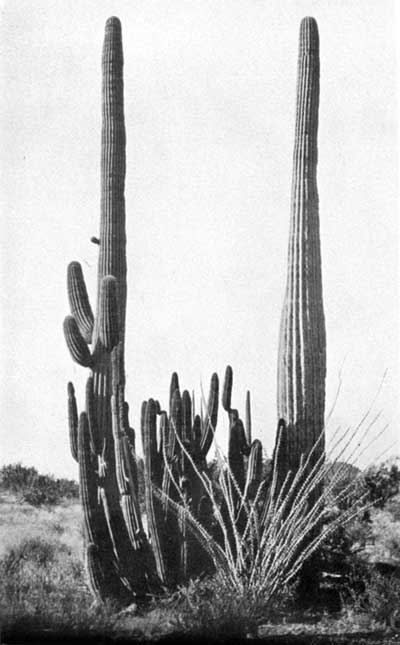

3. Organ Pipe Cactus Area, Arizona.—The two most spectacular, species of cactus in the United States are the saguaro (Carnegiea gigantea) or giant cactus, and the organ pipe (Lemaireocereus thurberi) cactus. The former is larger and more widely distributed and is the chief feature of the Saguaro National Monuments, near Tucson. The organ pipe cactus consists of a clump of separate stems, each about 6 inches in diameter, rising to a height of some 10 or 12 feet, and is found in the United States only in a comparatively limited area of southern Arizona. The area that has been suggested for a national monument lies south of Ajo, immediately to the west of the Papago Indian Reservation and adjoining the boundary between Mexico and the United States. It is remote from centers of population, is of primitive wilderness character, and lacks any important commercial use. The land is principally unappropriated and unreserved public domain, with the usual State school sections. The area includes a good representation of organ pipe cactus, some saguaro and other species of cactus, and typical desert species of plants and animals.

PHOTO 22.—Organ Pipe Cactus Area, Ariz. Showing saguaro cactus,

organ pipe cactus, and ocotillo.

4. Wayne Wonderland, Utah.—This is located on the Fremont River in Wayne County. It is principally public domain with some State school sections and has very little commercial use. The establishment of a national park or monument in this region was proposed by the Associated Commercial Clubs of Southern Utah. The area contains spectacular scenery of red and white sandstone formation, narrow gorges, several natural bridges, some cliff dwellings of prehistoric Indian tribes, petrified trees, and other features of interest. It is in a region that is now visited by few people other than local residents. If a project for a highway across the Colorado River to improve accessibility between south-eastern Utah and the rest of the State should materialize, this area would be on a route connecting Mesa Verde National Park with Zion National Park and its accessibility would be greatly increased.

PHOTO 23.—Wayne Wonderland, Utah. Looking up at Fremont River from

the upper end of River Gorge. Domes and cliffs of white and red sandstone.

5. Yampa Canyon, Colo.—Located in northwestern Colorado, and extending to the western boundary of the State, this area includes the scenic canyons of the Yampa River, and also the Lodore Canyon of the Green River. The canyons are principally in sandstone strata and have many vertical cliffs. At the junction of the Yampa and the Green Rivers is Pats Hole, which was called Echo Park by Major Powell because of the remarkable echo which repeats six or seven words, spoken rapidly. The area is a primitive wilderness, now utilized only for rather scant grazing. The region has few inhabitants, is remote from traveled routes, and cannot be reached by automobile. The Lodore Canyon was first explored by William Ashley in 1824, and has been traversed by a few parties of scientists and adventurers. A number of the caves have been occupied by prehistoric Indians. There are no stone dwellings among the archeological remains, but there are numerous granaries, artifacts, pictographs, and other evidence. This area is on the northern border of the region previously occupied by the cliff dweller or cave dweller. The land is mostly public domain, with the usual State school sections and a few tracts of privately owned land.

PHOTO 24.—Yampa Canyon, Colo. A typical rock wall in the Yampa Canyon.

6. Desert Plant Area, California.—One of the most picturesque and spectacular plants of the desert regions of the Southwest is the Joshua tree (Yucca brevifolia) or tree-yucca. The wood of this tree has some special uses, and it is also being cut for fuel because of the scarcity of other wood in its neighborhood. It is believed a representative stand of Joshua trees should be protected and held in public ownership. There is a suitable area in Riverside and San Bernardino Counties, Calif., southwest of Twenty-nine Palms and northeast of Palm Springs. The area has an interesting variety of desert plants and borders on both the Colorado and Mojave Deserts. There few native palms are found. Unlike much of the Joshua tree zone, it has scenic interest and variety. Readily accessible to the Los Angeles metropolitan district, the area will have extensive use and is correspondingly in need of protection. It is partly public domain and partly railroad land grant, with some State school sections and private land.

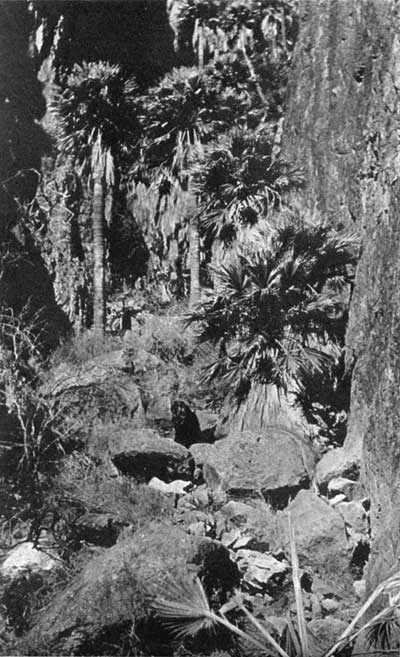

7. Kofa Mountains, Ariz.—There is only one area in Arizona where the native Washingtonia palm (Washingtonia filifera) is found and that is in the Kofa Mountains of Yuma County. The region is in a primeval condition and seldom visited. Its scientific value is probably greater than its recreational value at the present time. The land is mostly public domain. The area under consideration is about 36 square miles in extent. Signal Peak, the highest point of the Kofa Mountains, rises abruptly from the desert plain and has scenic value.

PHOTO 25.—Kofa Mountains, Ariz. Native Washingtonia palms; found

nowhere else in Arizona but in the Kofa Mountains.

8. Channel Islands, Calif.—There are eight islands in this group. The three largest and most desirable—Santa Catalina, Santa Cruz, and Santa Rosa—are privately owned. The other five—San Clemente, Santa Barbara, San Nicholas, Annacapa, and San Miguel—are Government land under the administration of the United States Bureau of Lighthouses. That Bureau has need for only a few lighthouse locations and would be willing to have the remainder of the islands used for other purposes. The Navy may have a use for one of the islands as an airplane field. A marine national park would be of much public interest and value. It would offer features of national interest that are not now represented in any of the present national parks. If some portion of the three larger islands were to be acquired for use as a base, the entire group could be used for a marine park offering excellent opportunities for the observation and study of marine life, as well as fishing, boating, swimming, and other sports. The islands have some rare plants, including the Torrey pine, some fossil remains of the imperial elephant, and extensive archeological remains of Indian villages. Geologic evidence clearly shows that at one time these islands were connected with the mainland and old beach lines, now high above the sea level, indicate that at another time the islands were more deeply submerged than at present.

PHOTO 26.—Channel Islands, Calif. The south shore of Anacapa Island,

which is Federally owned. Numerous sea lions frequent the rocks.

9. Meteor Crater, Ariz.—This is the location of a great crater that has been formed by the impact of a meteor with the earth. One scientist has referred to it as "the most interesting spot on the earth's surface." The meteor probably fell several thousand years ago. The crater is some 500 feet deep and some 4,000 feet in diameter. A large mass, or many detached masses of meteoric iron ore, rich in nickel, are believed to be located under the southern rim of the crater at a depth of 1,300 feet. The presence of some meteoric iron has been verified by drilling. The crater is owned by a mining company which hopes to mine the nickel ore, but which, as yet, has been unable to overcome the difficulties encountered, one of which is that the meteor is below the plane of water level. Probably within a few years either the mineral values will have been removed or else the attempt will be abandoned. The area is suitable for a national monument whenever title to the land may be acquired by the Government.

10. Indian Mounds along the Mississippi River in Iowa, Minnesota, and Wisconsin.—Among the interesting archeological remains in the United States are the ruins of cliff dwellings and pueblos in the Southwest and the Indian mounds of the North Central States. Some of the most valuable of the mounds are those grouped along the upper Mississippi River. State officials and organizations interested in conservation have proposed the best of these mounds, most of which are now in private ownership, be acquired, placed in public ownership and designated as a national monument. These mounds or burial places, frequently located on top of the bluff overlooking the Mississippi River, are of three types—lineal, conical, and effigy; in some cases the bones have been transferred from other locations. The region is scenically attractive as well as of high archeological value.

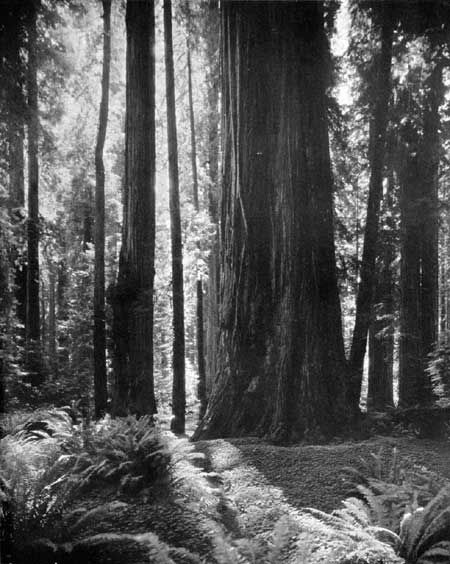

11. Redwoods, California.—There are two types of Sequoia: The "Big Trees" (Sequoia gigantea) and the coastal redwoods (Sequoia sempervirens). Groves of the former are included in Sequoia, General Grant, and Yosemite National Parks, and other groves are in State parks and in national forests. A grove of the coastal redwood is included in the Muir Woods National Monument. Better groves are now in California State parks. The redwoods are found in a narrow and intermittent strip a short distance back from the coast. The northern end of this strip is near the California-Oregon boundary line and the southern extremity is near Monterey. Most of the redwoods are in private ownership. Much of the original stand has been logged, and the rate of present and future logging depends largely upon economic conditions of the lumber industry. These redwoods are the outstanding forests of the United States and the finest stands should be preserved for future generations. The State of California has made important progress in acquiring some of the groves. Additional redwood forests should be acquired for preservation in their original condition before it is too late. They are unquestionably eligible for status as a national park.

PHOTO 27.—Redwood Belt, Calif. In southern Humboldt County. Photo by Moulin.

12. Big Bend Country, Texas.—Most of this region is in a primitive wilderness condition. It is bounded on the south by the big bend of the Rio Grande, and is adjacent to the international boundary between the United States and Mexico. The Rio Grande, within this area, passes through three great canyons: The Santa Helena, the Mariscal, and the Boquillas. These gorges, from 1,200 to 1,500 feet deep, are highly spectacular. The scenic Chisos Mountains, an isolated group, are also within this area. Rising to a height of 6,000 feet above the Rio Grande, they offer remarkable views. This is one of the most southerly regions of the United States, and contains some unusual animals and many rare plants. Sections of the area are of desert character, but portions of the Chisos Mountains section are well wooded. This is believed to be the most scenic area in Texas and eligible for a national park, and its establishment as such is advocated by officials of the State. Most of the land is in private ownership, though of a low value per acre. The State owns some 200,000 of the million acres in the area under consideration. There is no public domain in Texas.

13. The Lake Region of Northern Minnesota.—This region contains innumerable lakes and a network of waterways that offer splendid canoeing, fishing, and camping facilities. Much of this area is believed to be of greater value for recreational purposes than for commercial utilization. It should be kept in its wilderness condition, without unnecessary roads or other development. Part of this area is now in the Superior National Forest.

PHOTO 28.—Big Bend, Tex. Santa Helena Canyon, some 1,200 feet deep,

on the Rio Grande. The left cliff is in Mexico, the right cliff is in

the United States.

14. The White Mountains of New Hampshire and the Green Mountains of Vermont.—These mountains are among the most scenic portions of the Appalachian Range and it is believed that their recreational value outweighs the values that might be obtained by the commercial utilization of their resources. Within a comparatively short distance of heavily populated areas, they offer a recreational ground accessible to many. Parts of the area are now in the White Mountain National Forest and in the Green Mountain National Forest.

15. Luquillo Forest, P. R.—This forest is more tropical in character than any portion of the continental United States. It is in an isolated mountain mass at the eastern end of the island of Puerto Rico, known as the Sierra de Luquillo. The area is rugged and has numerous streams. The rainfall is high, varying from 130 to 150 inches annually. Every hill and gorge is clothed with a tropical rain forest, containing a combination of large hardwoods and tall mountain palms. In the lower reaches of the forest are many beautiful tree ferns. Most of this area is in the Luquillo National Forest. The greatest values of the Luquillo Forest will be secured by its utilization for public recreation, watershed protection and perpetual preservation as an unspoiled example of a high mountain tropical rain forest.

16. Okefenoke Swamp, Georgia and Florida.—This is believed to be one of the two swamp areas of the United States with such high scientific and scenic values that they should be in public ownership and retained in their primitive condition.

17. Dismal Swamp, Virginia and North Carolina.—Similar to Okefenoke Swamp already mentioned.

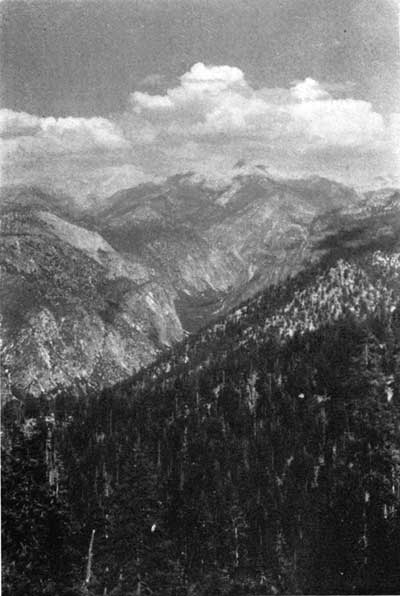

18. High Sierra Nevada country, California.—There is a strip of country along the crest of the Sierra Nevada of outstanding scenic value, which would link together Yosemite, General Grant, and Sequoia National Parks and the Kings River Canyon. This strip is now within national forests, but includes large areas that are above timberline, other areas of noncommercial timber, and still other areas where the recreational value is greater than the commercial value of both timber and grazing. This area is of such superlative scenic character that if it were not already in national forests it would be reserved as a national park, and since it is of greater value for recreation than for commercial use, it is believed it should be under the same jurisdiction as the adjacent national parks. Most of the area is of high elevation and remote from main roads. It would be desirable to include two extensions to lower elevations on the east face of the Sierra and in a few places lower areas would be included to furnish bases for accessible camp sites and other public facilities. In general this area would include regions of superb scenery of national importance, in which recreational values outweigh commercial values. It would link into one great national park what is now three established national parks, and the intervening area now under national forest administration.

PHOTO 29.—High Sierra Country, Calif. Kings River Canyon.

19. The Cascade Range, Wash. and Oreg.—There are a number of spectacular volcanic cones, also a variety of superlative mountain scenery in the Cascade Range of Washington and Oregon. Mount Rainier, one of these peaks, is an established national park. The other principal peaks would be reserved as national parks if they were not already in national forests. The Forest Service has designated large tracts in the Cascade Range as recreational areas and it is generally recognized that their value for recreation exceeds their value for commercial utilization. Since they contain scenery of national value, and since their chief use is recreation, it would seem that they should be designated as national park lands. The area proposed would include Mount Rainier, Mount Baker, Mount St. Helens, Mount Adams, Glacier Peak, and other outstanding peaks in Washington; and Mount Hood, Mount Jefferson, Three Sisters, and other spectacular peaks in Oregon. The total area would reserve as a national park some of the finest and most spectacular scenery of the country, and would preserve areas whose best uses are for watershed control, game preservation, and education and recreation.

Mount St. Helens with an elevation of 9,671 feet is perpetually snowcapped. Most symmetrical of all the volcanic cones of the Cascades, it is considered by many to be the most beautiful.

Mount Adams is similar to Mount Rainier in grandeur of bulk, mass, and general rugged aspect. Its elevation is 12,307 feet. The surrounding country is especially wild, undeveloped, and unpopulated.

Mount Baker, elevation 10,750 feet, is designated as Mount Baker National Forest Park, in recognition of its scenic rather than commercial value. Mount Shuksan, elevation 9,038 feet, is also scenic, and both Mount Baker and Mount Shuksan have large glaciers and perpetual ice caps.

The Glacier Peak region is rough, inaccessible, and not frequently explored. Glacier Peak is 10,436 feet in elevation.

The peaks in Oregon, including Mount Hood, Mount Jefferson, and Three Sisters, are of the same general type and their recreational use is national in character.

All of these peaks are of national park quality and might be grouped as one great national park—or two parks might be established, one in Washington and one in Oregon. In some cases the peaks would be detached areas, and in other cases some of the peaks might be connected.

20. Colorado River, Utah and Ariz.—One of the great wilderness areas of the United States is in southeastern Utah and northern Arizona, on both sides of the Colorado River, from its junction with the Green River to Grand Canyon National Park. This section of the Colorado River contains many spectacular gorges. Some of them have been seen by only a few adventurous explorers. The area has scant grazing value, but very high scenic quality and great geologic interest. It seems desirable to reserve a liberal area in public ownership. The present use is so small there would be little conflict with commercial interests. The population of the area is considerably less than one person to a square mile. As an indication of the absence of travel in this region at present, it may be mentioned that there is no road across the Colorado River between Moab, Utah, and Lees Ferry Bridge, Arizona, a distance of about 170 miles. The present value of this area is small; its future recreational value will be great.

21. Green River, Utah and Colo.—The Green River, from Flaming Gorge, Utah, through the Canyon of Lodore, in Colorado, and back into Utah, through numerous gorges to Split Mountain, is highly scenic in character. Some of the people of Utah halve proposed a national park in this area. The area under consideration would include the Yampa Canyon, previously referred to, as well as the Dinosaur National Monument.

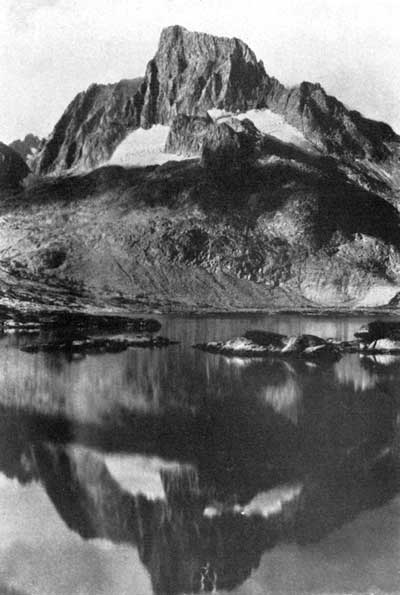

PHOTO 30.—High Sierra Country, Calif. Banner Peak.

There are on file some 138 proposals for additional national parks and monuments. Many of these have not been investigated. Presumably the greater part will be found to possess insufficient national interest to justify their establishment as Federal parks or monuments, but among the list it is believed there are some areas, in addition to those mentioned that should be reserved or acquired for national use.

These proposed areas may be classified approximately as follows, based on their chief feature of interest:

| Number of areas | |

| 1. Scenic: | |

| (a) Mountains | 22 |

| (b) Canyons | 10 |

| (c) Forests | 2 |

| (d) Lakes, lake shores, and islands | 4 |

| (e) Marine, ocean beaches and islands | 3 |

| (f) Caves | 3 |

| (g) Various | 11 |

| Total scenic areas | 55 |

| 2. Scientific: | |

| (a) Thermal | 1 |

| (b) Botanic | 6 |

| (c) Zoologic | 2 |

| (d) Geologic | 1 |

| (e) Paleontologic | 2 |

| (f) Ethnologic | 1 |

| Total scientific areas | 13 |

| 3. Prehistoric: | |

| (a) Cave dwellings and pueblos | 6 |

| (b) Pictographs | 6 |

| (c) Mounds | 2 |

| (d) Other | 2 |

| Total prehistoric | 16 |

| 4. Historic: | |

| (a) Exploration and discovery | 9 |

| (b) Migration and settlement | 7 |

| (c) Colonial period | 1 |

| (d) Military (forts and battlefields) | 17 |

| (e) Places associated with national characters | 15 |

| (f) Invention and industry | 2 |

| (g) Other | 3 |

| Total historic | 54 |

Reaches of the Ocean and Great Lakes.—In respect to one extraordinarily important resource for the enjoyment of a wide range of recreation, namely, ocean and Great Lakes shores, the publicly owned recreation facilities of the United States are seriously lacking. While there are numerous points of public access to beaches in many coastal States, those that are in private ownership, which cater to a far greater volume of use than all those publicly owned, are usually very limited. The maximum of use is usually concentrated upon them and they almost invariably are associated with a crowded, unplanned, and garish conglomeration of structures that frequently is little more than a beach slum.

Of the New England coast, only about 56 miles are in public ownership for recreational use, with approximately 35 miles of beach. Years of effort and clamor have not yet brought any of New Jersey's picturesque and valuable coast line into State ownership. The same is true of Delaware. Maryland, with a limited frontage on the open Atlantic and hundreds of miles on Chesapeake Bay, has not acquired an inch.

Virginia has, in actual ownership, 1,000 feet of frontage on salt water and this lies inside the Virginia capes. North Carolina owns a small amount of beach at Fort Macon; South Carolina has half a mile near Myrtle Beach; Georgia and Florida have none. Of the Gulf States, Texas is the only one owning any frontage on the Gulf (4.8 miles), and that is unsuitable for bathing. In the proposed Everglades National Park is a long coast line on the Gulf with a limited extent of excellent beach.

New York alone, of all the east and south, has had both the wealth and the will to provide any considerable extent of beach or other coastal frontage. Jones Beach, Orient Beach, Montauk Point, Hither Hills, Sunken Meadow, and other properties—10 in all—on the shores of Long Island comprise the most extensive and valuable holdings of this type in the possession of any State, with frontage totaling 55 miles, of which 34-1/2 miles are beach. Jones Beach carries the heaviest annual volume of use per acre of land of any State park in America. These properties serve the population of Greater New York and Long Island, but they are so difficult of access from more distant points as to be of comparatively slight interstate service.

The situation on the Pacific coast is somewhat better than that on the Atlantic. As part of her $12,000,000 park purchase program, California has acquired 52.5 miles of frontage, of which 29.79 miles are beach on the Pacific Ocean, its bays and inlets. Of this total, the bulk is in southern California. Several of these are properties described as "frontage on ocean, 6,000 feet; acres, 0," which indicates that for the most part they include little, if any, of the picturesque uplands that lend so much picturesqueness to her beaches.

"The State of California, and municipalities created by and holding from it, broadly speaking, now possess title, in trust for the people, to the entire coast of California between ordinary high tide and low tide, and to the submerged lands beyond so far as that ownership can be made effective."12 The actual use the beach is often controlled by the ownership of the abutting property. At high tide all of the strip owned by the State is submerged. Convenient access to the beach is essential to its full use by the public. Buildings for public use must be located on adjacent property. Therefore the beaches serve their full recreational use only when the State owns the property fronting on the coast.

12 Report of State Park Survey of California, prepared for the California State Park Commission by Frederick Law Olmsted, California State Printing Office, Sacramento, 1929.

Oregon's sole park water frontage is 23.6 miles in length, with 7.8 miles of beach. These properties are highly picturesque but limited largely to those sections of her coast where the mountains meet the sea, or to rugged shores where bathing is limited and somewhat hazardous. Four hundred and twenty miles of the State's 450-mile shore is owned by the State between high and low water, and has the legal status of a public highway. Washington's State-owned frontage resembles that of Oregon in picturesqueness and beauty. It lies on Puget Sound, Hood Canal, and the bays that open on the Strait of Juan de Fuca. It is a notable fact that of her 13 miles of salt water frontage, more than 11 are on properties obtained from the Federal Government without cost to the State.

For the entire United States, the States own 206.6 miles of frontage on salt water with 110.5 miles of beach. As previously stated, the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey reports that the total length of tidal shore line of continental United States, measured by a unit 1 mile long, is 21,862 miles. The total ownership of coastal property included in all of the State park systems is only 1 percent of the total tidal shore line of the United States. The possibilities for increased public recreational use of the seacoast are tremendous.

New York, Pennsylvania, Michigan, Indiana, Wisconsin, and Minnesota all possess parks fronting on the Great Lakes, though those of Wisconsin and Minnesota possess slight value for intensive recreation. Ohio, with its long frontage on Lake Erie, has not devoted a foot of it to recreation; neither has Illinois on her more limited Lake Michigan frontage. The total State-owned Great Lakes frontage is 63.9 miles with 26.4 miles of beach.

National Park Policy for Wildlife Administration.— One function of the national parks is to preserve the flora and fauna in their primitive state and to provide the maximum opportunity for their observation.

In the present state of knowledge, and until further investigations make revision advisable, it is believed that the following policies will best serve this dual objective as applied to the vertebrate land fauna.

Relative to areas and boundaries:

1. That each park shall contain within itself the year-round habitats of all important species belonging to native resident fauna.

2. That each park shall include sufficient areas in all these required habitats to maintain at least the minimum population of each species necessary to insure its perpetuation.

3. That park boundaries shall be drafted to follow natural faunal barriers, the limiting faunal zone, where possible.

4. That a complete report upon a new park project shall include a survey of the fauna as a critical factor in determining area and boundaries.

Relative to management:

5. That no management measure or other interference with biotic relationships shall be undertaken prior to a properly conducted investigation.

6. That every species shall be left to carry on its struggle for existence unaided, as being to its greatest ultimate good, unless there is real cause to believe it will perish if unassisted.

7. That, where artificial feeding, control of natural enemies, or other protective measures are necessary to save a species unable to cope with civilization's influences, every effort shall be made to place that species on a self-sustaining basis once more.

8. That the rare predators shall be considered special charges of the national parks in the proportion that they are persecuted everywhere else.

9. That no native predator shall be destroyed on account of its normal utilization of any other park animal, excepting if that animal is in immediate danger of extermination, and then only if the predator is not itself a vanishing form.

10. That species predatory upon fish shall be allowed to continue in normal numbers and to share normally in the benefits of fish culture.

11. That the numbers of native ungulates occupying a deteriorated range shall not be permitted to exceed its reduced carrying capacity and, preferably, shall be kept below the carrying capacity until the range can be brought back to original productiveness.

12. That any native species which has been exterminated from the park area shall be brought back if this can be done, but if said species has become extinct, no related form shall be considered as a candidate for reintroduction in its place.

13. That any exotic species which has already become established in a park shall be either eliminated or held to a minimum provided complete eradication is not feasible.

14. That the threatening invasion of the parks by other exotics shall be anticipated; and to this end, since it is more than a local problem, encouragement shall be given for national and State cooperation in the creation of a board which will regulate the transplanting of all wild species.

15. Presentation of animals. That presentation of the animal life of the parks to the public shall be a wholly natural one.

16. That no animal shall be encouraged to become dependent upon man for its support.

17. That problems of injury to persons or to their property or to the special interests of man in the park shall be solved by methods other than killing the animals or interfering with their normal relationships where this is at all practicable.

18. Relative to faunal investigations. That a complete faunal investigation, including the four steps of determining the primitive faunal picture, tracing the history of human influences, making a thorough biotic survey, and formulating a wildlife administrative plasm shall be made in each park at the earliest possible date.

19. That the local park museum in each case shall be repository for a complete skin collection of the area and for accumulated evidence attesting to original wildlife conditions.

20. That each park shall develop within the ranger department a personnel of one or more men trained in the handling of wildlife problems who will be assisted by the field staff appointed to carry out the faunal program of the Service.13

13 From Fauna of the National Parks of the United States, by George M. Wright, Joseph S. Dixon, and Ben H. Thompson; Government Printing Office, 1933.

National Capital Park System.—The National Capital Park system of the District of Columbia and its environs is administered by the National Park Service of the Interior Department. It comprises within the District 680 separate properties totaling approximately 5,334 acres, and in the adjoining States of Maryland and Virginia about 1,1266 acres. In the District of Columbia 3,053 acres or 57.2 percent are developed; 458 acres or 8.6 percent partially developed, and 1,823 acres or 34.2 percent undeveloped. Of the 1,166 acres in the States of Virginia and Maryland approximately 80 percent is undeveloped.14

14 Statistics from an unpublished statement of the National Capital Park Office entitled "National Capital Parks Reservation List", Revised to May 1, 1934.

An integral part of the regional recreational plan are the properties under the jurisdiction of the Maryland National Capital Park and Planning Commission in suburban Maryland.

In the District of Columbia there are also certain properties which functionally are a part of the recreational area system of the National Capital but not under the immediate jurisdiction of the National Park Service. These include several properties under the Playground Department of the District Government, school properties suitable for playground or playfield purposes under the Board of Education; the National Zoological Park under the Smithsonian Institution; the National Botanic Garden; the Capitol Grounds, and other areas under the Joint Library Committee of Congress; the Agricultural Department grounds and the National Arboretum under the jurisdiction of the Department of Agriculture.

The properties of the National Capital Park System may be classed as follows:

1. Circles, Ovals, Triangles, and Parklike Strips in Streets.—These are numerous but their total acreage is comparatively small. They are usually formally landscaped when developed. They serve as beauty spots, safety zones, and as sites for statues or other memorials.

2. Small In-town Parks or Squares.—These were for the most part set aside in the original plan of the city. They are formally landscaped when developed and serve as rest and relaxation places and as informal playgrounds for very young children.

3. Playgrounds and Playflelds.—These areas are of comparatively recent origin in the system and as yet are entirely too few in number and acreage to serve adequately the active adults of the city. Playgrounds are intended to provide convenient and properly equipped places for the play of the children of the city, while the playfleld or recreation center is designated to provide readily accessible opportunities for the sports and games of the youth and active adults.

4. Formal Landscaped Areas Which Provide Settings for Public Structures.—They serve also as rest and relaxation places and in some instances provide opportunities for active recreations. The Mall is a typical example of this kind of area.

5. Large Parks.—These are for the most part naturalistic or landscaped areas preserving the water front of the Potomac and Anacostia Rivers, the watersheds of various small streams in the District and the region, and areas of historic and scenic interest. Some of these properties are highly developed from the landscape viewpoint while others are kept in a naturalistic condition. Typical examples of large water front landscaped areas are East and West Potomac parks. These are developed chiefly for various kinds of active recreation, as is also true of the Anacostia River front and valley.

Typical examples of areas kept in a more or less naturalistic condition are Rock Creek Park, which reserves and protects the forested watershed of Rock Creek and some of its tributaries, the Glover-Archbold Park; the large area along the Potomac River comprised in the Mount Vernon Memorial Parkway, including Fort Hunt; Fort Dupont in the District; and other historic areas.

6. Parkways and Boulevards.—The parkways are chiefly parts of the water-front and stream-valley properties mentioned immediately above. The proposed Fort-to-Fort Drive will be a combination of both a parkway and a boulevard, forming a connecting loop through the suburban sections of the District and contacting nearly all the major park properties and many of the active-recreation areas.

The metropolitan character of the National Capital Park System is at once apparent from the foregoing statement of its present status, comprising areas both within the city and outside its boundaries.

There are several reasons which have inspired the extension of the park system into the region about the city and District and that make it desirable to continue this policy. Among these are the arbitrary and unnatural boundaries of the city, the expansion of the population and its overflow into the surrounding region, the great need for outdoor recreations of a working population so largely engaged in executive and of clerical pursuits, and the high per capita ownership of automobiles which enables a large percentage of the people to seek outdoor recreations beyond the boundaries of the city.

Unlike the park systems of other large cities of the United States, the National Capital park system is essentially national in character. While the system serves the recreational needs of the residents of the District and its environs it also provides recreational services to very large numbers of the people of the United States who are drawn to the city because it is the Capital of the Nation. The national character of the parks of Washington is clearly stated in the language of the act of September 27, 1890, providing for the establishment of Rock Creek Park: "that a tract land * * * shall be secured, as hereinafter set out, to be perpetually dedicated and set apart as a public park and pleasuring ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people of the United States."15 Because Washington is the Nation's Capital and the District of Columbia a Federal district, the providing of open spaces for parks and recreation always has been dependent on legislative action of Congress. "Prior to the passage of the act of June 6, 1924 (43 Stat. L., 463), creating the National Capital Park Commission, all park areas except those shown on the plan of the original city and small areas outside the original city at street intersections, were created by special acts of Congress.16

15 The italics are the Editor's.

16 Schmeckebier, Laurence F., The District of Columbia; Its Government and Administration, Washington, D. C., Institute for Government Research, 1928, p. 662.

The creation of the National Capital Park Commission, the members of which are appointed by the President, except certain ex-officio members, marked a most important step in the history of park planning and development in the National Capital and its environs. The Commission was specifically charged under the act creating it "to acquire such lands as in its judgment shall be necessary and desirable in the District of Columbia and adjacent areas in Maryland and Virginia * * * for suitable development of the National Capital park, parkway, and playground system" (act of June 6, 1924—43 Stat. L., 463, sec. 2). By act of April 30, 1926 (44 Stats. 374) the powers of the Commission were enlarged and its name changed to the National Capital Park and Planning Commission. The object of this change was stated as being "to develop a comprehensive, consistent, and coordinated plan for the National Capital and its environs in the States of Maryland and Virginia, to preserve the flow of water in Rock Creek, to prevent pollution of Rock Creek and the Potomac and Anacostia Rivers, to preserve forests and natural scenery in and about Washington, and to provide for the comprehensive, systematic, and continuous development of park, parkway, and playground systems of the National Capital and its environs."

Acting under the authority of the congressional legislation of 1924 and 1926, together with subsequent legislation, the National Capital Park and Planning Commission prepared a comprehensive plan of parks, parkways, and playgrounds.

The plan comprised two general groups of properties.

First. A system of active-recreation areas, playgrounds, and recreational centers. This suggested system included 226 major recreational centers and approximately 130 playgrounds. The total area of this proposed system of playgrounds and recreational centers is 1,068 acres.17 The plan involved the use of suitable school sites, properties belonging to other public agencies where arrangements could be made for such use, and the direct purchase of additional sites or extension of existing sites by both the School Board and the National Capital Park and Planning Commission. Considerable progress has been made in the acquisition of sites under this plan and some progress made in development of sites but, in general, it may be said that the chief defect of the park-recreation system of the National Capital as it exists today is in the inadequacy of spaces for children's playgrounds and playfields. Juvenile delinquency among the children is very high in those sections of the city lacking playgrounds, and the rate of delinquency among the youth of the city is appalling.

17 Statistics from an unpublished statement or the National Capital Park and Planning commission dated Nov. 1, 1911.

It is urgently recommended that Congress make available the necessary funds for carrying forward as speedily as possible the plans of the National Capital Park and Planning Commission for playgrounds and playfields and, especially, for completing acquisition of and making usable those projects already begun.

Second. The second group of areas in the comprehensive plan comprises areas intended to preserve the forests and natural scenery and historic sites in and around Washington, to restore the purity of the waters of Rock Creek, the Potomac, and Anacostia Rivers, protect the watersheds of streams tributary to Rock Creek and the above-mentioned rivers, and to preserve water-front areas, and areas suitable for parkways and boulevards.

Of that part of the general plan comprising properties in the region, the acquisition and development of the water front of the Potomac River from the Memorial Bridge to Mount Vernon has been accomplished as the first unit in the George Washington Memorial Parkway; Fort Foote on the Maryland side of the river and Fort Hunt on the Virginia side have been transferred by the War Department; and certain key properties at Great Falls and control over certain places in the bed of the river have been obtained.

Within the District, through purchase, gift, transfer, or allocation, much progress has been made in securing properties along the Potomac River especially in the southern part of the city. Three-quarters of the lands for the Fort-to-Fort Drive have been secured, including practically all the historic fort sites.

In Maryland, the Maryland National Capital Park and Planning Commission has acquired, through funds loaned and contributed by the Federal Government, 7 miles of stream valley parks totaling 580 acres. These not only add further protection to the watershed of Rock Creek and to certain tributaries of Anacostia River but also provide many opportunities for active recreation.

Outstanding among the regional projects is the George Washington Memorial Parkway, or River Valley Park, extending along both sides of the Potomac River for approximately 30 miles, from Mount Vernon on the south to and including the Great Falls on the north, and also including the historic Chesapeake and Ohio Canal and the Potowmack Canal constructed by George Washington. To insure this and future generations against despoliation of the banks of the Potomac River by objectionable and undesirable commercial enterprises already taking place; to preserve the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal not only because of its great historic value but also because of its recreational potentialities; and to retain the Great Falls of the Potomac in their natural state it is urgently recommended that Congress, as rapidly as possible, make available the necessary funds for carrying forward this project.

It is further recommended that Congress, as soon as practicable make funds available for complete acquisition of projects already under way in the District. The Park and Planning Commission has 50 such projects in the District in various stages of acquisition in which more than $5,500,000 have been invested for land acquisition. The Commission estimates that will require $2,000,000 to complete two-thirds of these; $3,500,000 would complete all of them. These projects include a large number of the much-needed playgrounds and neighborhood recreation center areas.

It also is strongly recommended that Congress make funds available for the progressive development of areas already acquired so that people may have the benefit of their use at the earliest possible date. This recommendation has special reference to the development of areas for playgrounds and recreation centers.

The present and proposed future expansion of the park-recreation system in the District and its environs together with a constantly expanding program of recreational services raises the question as to the best form of administration of recreation in the District and the region. At the present time the administration of public recreation is divided among three principal agencies: the National Capital Park Office of the National Park Service, the Playground Department of the District Government, and the Community Center Department of the Board of Education. Some plan of unification and coordination is highly desirable in order to secure maximum service from funds appropriated and from properties and facilities now available and to be provided in the future.

Considering the metropolitan and national character of the park-recreation system of the District of Columbia and its environs; and considering also that most of the facilities for outdoor recreation are under the control of the National Capital Park Office of the Park Service and that this Office is well equipped to handle all problems in design, construction, and maintenance of areas and facilities and that its Recreation Division could readily be expanded into a program administering agency, it is recommended that public park-recreation administration be unified and coordinated through the National Capital Park Office and that it work in close cooperation with the Board of Education and other public agencies rendering recreational services in the District.

It is further recommended that an advisory park-recreation committee composed of certain ex-officio members and outstanding citizens of the community be appointed to advise with the executive park-recreation officials of the National Capital Park-Recreation Office concerning the development and administration of a comprehensive program of recreational service in the District and its environs.

Continued >>>

Last Modified: Fri, Sep. 5, 2003 10:32:22 am PDT

http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/recreational_use/chap4-4c.htm

![]()

Top

Top