|

DESCENT OF THE CANYONS

By Norman D. Nevills.

(Mr. Nevills, a resident of Bluff, Utah, is a veteran

explorer of the canyons of the Colorado, Green, and San Juan

Rivers.)

Green River, Wyoming, 10 A.M., June 20, 1940 - There

were eight of us, including two women, and we breathed sighs of pleasure

and anticipation as I gave the signal to push the three rowboats into

mid-stream. Nearly 1,200 miles of canyons and rapids were ahead of us -

scenery to hold the most critical, spellbound. By use of a map, we hoped

to find a great natural bridge that would rival or possibly surpass in

size the world's largest known natural stone arch, the Rainbow Bridge,

309 feet high, in Rainbow Bridge National Monument, Utah. Major John W.

Powell, early explorer of the Green and Colorado Rivers, left this same

place just 71 years before us. This would be the first time that women

had attempted to follow the course set by the intrepid Major in 1869.

The 200 or so persons in the interested and friendly town of Green River

were rapidly lost to view. Our adventure was started.

The Colorado River, as we know it in the Grand

Canyon, has its source in the high mountains of Colorado and Wyoming.

Near the upper reaches of the proposed Escalante National Recreational

Area in Utah, the main Colorado River has its inception at the Junction

- the confluence of the Upper Colorado and the Green Rivers. Tradition

and interest are established in the canyons formed by the Green River to

the Junction, and a more remarkable and colorful series of canyons would

be hard to find.

The first few days of our trip saw us in the

relatively open country south of Green River, Wyoming. We became used to

our boats and their handling. The design of these boats was evolved from

a number of years' study of different types of craft used on my trips

on the San Juan River. These latest models were 16 feet long, 6 feet

wide, one-third open, and contained 7 water-tight compartments. They

were well adapted for rough water. My lead, or pilot boat, the WEN, was

also my lead boat in 1938 when I went from Green River, Utah, to Boulder

Dam during high water. Aside from design, an innovation in boat

construction was the use of a special 5-ply marine plywood. This

material, with its amazing strength and durability, assured us of

almost indestructible crafts.

About 68 miles below Green River, Wyoming, we entered

the portals of Flaming Gorge, Colorado, in the Dinosaur National

Monument. This was the first of the sixteen canyons we would pass

through to Boulder Dam. Sundown lights accentuated the red cast of the

deep canyon, and it was a real flaming gorge in which we made Camp No.

3. Our large load capacity simplified the camping problems. Two compact

nested cooking sets were ample for all meals. We used canned goods

almost without exception, and the menus were prepared in advance of our

starting, by my wife, Doris. Her unfailing good nature and cheerfulness

in trying situations throughout the trip contributed much to our

success. Her past river experience proved in good stead in preparing the

menus. This system conserved supplies, as we at all time knew exactly

what to open. Doris prepared all the meals, assisted by the other woman

voyager, Miss Mildred Baker of Buffalo, New York.

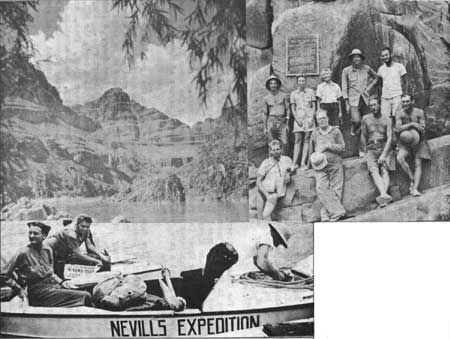

Near the end of the trail, the explorers were photographed in Separation

Canyon, at the plaque commemorating Major Powell's expedition of 1869,

when two men who climbed the canyon wall were killed by Indians. Mr.

and Mrs. Nevills are at extreme left, in top row. Photo at upper left

is of the lower Granite Gorge, in Grand Canyon.

The day following our entrance into Flaming Gorge, we

passed through Horseshoe and Kingfisher Canyons, on down into our first

real rapids, in Red Canyon. It was a welcome change to be in the depths

of these beautiful canyons; our progress was faster, the water was more

interesting, and the scenery was of incomparable beauty.

Early each morning, Doris would write a resume of our

previous day's events and send the message to the Salt Lake City

newspapers, by carrier pigeon. It was a thrilling sight to see the birds

swoop up and strike an unerring course. On a few occasions film was sent

out this way, and a few hours later the pictures were printed in the

newspapers.

Each succeeding mile brought us into deeper canyons,

and into rapids that increased in their furry. Our passage through

Lodore Canyon was marked by a near accident when one of the boats was

tossed up on a rock in Disaster Falls. Triplet Falls and Hell's Half

Mile were run successfully, and that saw us through the steepest part of

the Green River. There is a drop of 25 feet in Hell's Half Mile. Just

above Jensen, Utah, we landed the boats and walked one mile to see the

dinosaur quarry and the museum, in Dinosaur National Monument. Part of

the monument is in Utah, and part in Colorado. Nowhere else in the world

have dinosaur remains been found in such abundance and concentration as

in this quarry.

Day by day the miles were put behind us. There was

never a tiresome moment; always something new and different to interest

us. Time and distance passed quickly, and almost before we could realize

it we were down to Green River, Utah, one-third of our journey

completed. Here we stayed a couple of days to take on more supplies, get

out letters, and visit with friends and relatives who came to see us.

Here B. W. Deason, Salt Lake City assayer, left us, to rejoin the party

at Bright Angel, in Grand Canyon National Park. His place was taken by

Miss Anne Rosner, Chicago school toacher. Also to join the party was

Barry Goldwater, Phoenix merchant, and Arizona historian. For the next

117-1/2 miles through the Labyrinth and Stillwater Canyons to the

junction with the Colorado River, we would have smooth water unbroken by

any rapids. For this stretch we used outboard motors to relieve the

monotony and tiresomeness of rowing. And then would come Cataract

Canyon, the "Graveyard of the Colorado." The rapids to be encountered

there would pale to insignificance the rapids of the Green River. We all

felt undaunted, as our equipment and personnel were believed to be

adequate for the task.

Handling my other two boats, the JOAN, named after

our 3-year-old daughter; and the MEXICAN HAT II, were two men whom I had

trained on previous trips. Dr. Hugh Cutler, botanist of the Missouri

Botanical Gardens, handled the Mexican Hat II, and he also spent all

possible time in gathering flora and making a study of plant life. Dell

Reid, a prospector, and member of my 1938 expedition, guided the Joan.

Our photographer was C. W. Larabee, of Kansas, genial and excellent all

round man. Larabee's pictures were supplemented by the excellent

photography of Barry Goldwater, known for his photographs of Arizona.

Mining Engineer J. S. Southworth of California, rounded out our crew.

The unexpected abilities of Mr. Southworth were a real asset.

r On July 10th, we were proceeding down the river.

The water was low, and sandbars were troublesome. Overnight camp was

made at a geyser that was developed during oil prospecting operations.

Passing the San Rafael River we entered Labyrinth Canyon, and crossed

the northernmost boundary of the proposed Escalante National

Recreational Area. We were here in the lovely orange tinted sandstones,

and abounding on each side were monuments of many types and

descriptions. Major Powell called this the "Land of Standing Rocks." I

hope that this little known and exceedingly beautiful section will soon

be made more accessible so that thousands of people can see and enjoy

its weird and magnificent grandeur. The canyon rapidly gets deeper; soon

we were between two almost polished walls, and only occasional views of

the tops were possible. Each of the many interesting side canyons, with

cliff ruins and surface sites of prehistoric dwellers, was a trip and

adventure in itself. The miles passed rapidly amidst all this charming

and interesting display. Nature must have been in an extra benevolent

mood for spreading beauty, when moulding this canyon.

July 14th - Junction of the Green and Colorado

Rivers! The confluence of the Green and Upper Colorado forms a mighty

and impressive river. The formation here gives way to immensely high

cragbound cliffs that would be formidable obstacles to anyone trying to

gain access to the rim. Bishop and Wayne McConkie of Moab, were here to

meet us, and to see us run the first little rapids of Cataract Canyon.

We had planned to stay here at least half a day, but impatience to start

the task of navigating Cataract Canyon was too much, and after hurriedly

writing letters for the McConkies to take out, we embarked again.

Cataract Canyon is only 41 miles long, but it is filled with innumerable

rapids, many of them very dangerous unless every precaution is observed.

This section, owing to the number of fatalities occurring to earlier

parties, was well named the "Graveyard of the Colorado." Our good

fortune held through here, and our passage was marked with but one

serious mishap. In rapid 24, Dell Reed, boatman involved in the Disaster

Falls experience, this time had a close call when he got off the

channel. It took us several hours of hard work to extricate Reed and the

Joan, and we were glad to crawl into our sleeping bags that night.

There are mountain sheep in this area, but very

little else except rabbits and rattlesnakes. Towards the foot of

Cataract Canyon is the lateral tributary, Dark Canyon. Fabulous tales

are told of great prehistoric ruins in this canyon, so we spent several

days here in an effort to penetrate up from the river as far as

possible. Much work resulted in only getting 7 or 8 miles into the

canyon. Waterfalls are a great problem, and I am convinced that the

Cliffdwellers never used the lower end of the canyon to reach the river,

as there are no pictographs or other indications. It would be worthwhile

entering from the head and working down, as the upper reaches were no

doubt occupied in the past.

Mille Crag Bend marked the terminus of Cataract

Canyon, and now for the next 184-1/2 miles of Narrow and Glen Canyons we

would relax on the relatively smooth water, and give ourselves up to the

fascinating and charming beauty of Glen Canyon. The rest would prove

welcome in preparation for the rough, heavy rapids of Marble and Grand

Canyons. To this point every rapid had been run, but I doubted if this

record would maintain, as the constantly lowering river was making for

extremely rocky channels.

Upon entering Narrow Canyon we again put on our

outboard motors, and the 9 miles were quickly put behind. We were

impatient for a sight of the Dirty Devil, or Fremont River, marking the

head of Glen Canyon. In 1869 Major Powell, upon reaching this point,

called to Jack Sumner: "Is it good water, Jack?" "No, she's a dirty

devil," replied Sumner. And truly apt is the name, as at all times the

stream seems to have a dirty, unpalatable flow of water.

Eight miles from here we stopped at Trachyte Creek,

or Hite, to visit the Chaffins. They have a ranch and do a little

mining. A pleasant visit was made here, but we all felt the urge to be

on our way and explore the canyon in which the bridge should be found.

Upon leaving Hite I divulged for the first time where I expected to find

the bridge. About 90 miles below, in a side canyon of the Escalante, we

would prove or disprove our information of the tremendous big natural

bridge. With the motor, and a smooth river we made good progress. But

the second night out from Hite, Doris injured her leg at the point of an

old break, and it looked to be broken again. This was a serious mishap.

We decided to wait until morning; then, if the leg wasn't better and

showed a break, we would get her to Lee's Ferry, 90 miles distant. The

next morning showed an improvement, and another day's rest saw my wife

able to hobble around, with the use of an improvised crutch.

We reached the Escalante River at noon, and after

lunch most of us started hiking up the canyon. A small stream of not too

brackish water had to be crossed and recrossed, but it proved a blessing

in the extreme heat. My information indicated that we must go up to a

lateral canyon coming in from the south, and known as Forty Mile Creek.

It lay some 8 miles from the Colorado River. A walk of a mile up Forty

Mile Creek would find the bridge, we hoped! By sundown we reached Forty

Mile Creek, and it was decided to spend the night at the mouth of the

creek. We ate dinner, then rolled out on the sand to enjoy a night's

sleep.

Next morning, after a hastily consumed breakfast, we

were again on our way. A 15-minute walk brought us to the bridge. And

such a bridge! As we gazed at it its enormity began to be appreciated

and we soon realized that here was no ordinary natural bridge, such as

the types that are found all over this region. This bridge was huge.

Pictures were soon being taken, and Dr. Cutler volunteered to accompany

me on an attempt at an ascent. After much work we were on top, and by

use of a silk line we were able to get the various dimensions. From the

top to the wash below was 305 feet, just four feet short of the Rainbow

Bridge. The span was 297 feet while the bridge measured 114 feet in

thickness.

It would be hard to describe the wonder and thrill

that we felt in seeing this second largest known stone bridge in the

world. In honor of Dr. Herbert E. Gregory, whose work in this desert

country has contributed so much to our knowledge, we named this the

"Herbert E. Gregory Natural Bridge." This bridge lies within the area

encompassed by the proposed Escalante National Recreational Area. The

best approach is by going down the San Juan River to the Colorado,

thence up stream by power some 10 miles to the Escalante River. Our walk

back to the boats was every bit as thrilling as in going up. This little

known canyon has a place of its own in great scenic beauty. The high

glossy walls of Navajo sandstone are superb in their breath-taking

sheerness and beautiful natural tapestries. Someday there will be

thousands of people admiring this canyon.

A full length book would be needed to describe the

endless beauties and places of interest in Glen Canyon. Practically all

the side canyons afford adventures. To the fortunate few who have

partially explored some of these side canyons reposes a knowledge of an

area that some day will be the "Playground of America." Leaving the

Escalante we visited the Hole-in the Rock, famous crossing of the early

day Mormons, and we wondered at the courage and fortitude of a group of

people treking across such rugged and almost impassable country.

Outstanding of all the Glen Canyon attractions was our visit to Rainbow

Bridge, in the Rainbow Bridge National Monument. So much has been

written about Rainbow that it is unnecessary for me to elaborate. It is

significant, though, that "Nonneshosie" held us spellbound, in spite of

all the spectacular scenery to which we had become accustomed.

Almost too soon were we at the mouth of Glen Canyon.

On August 2, our three boats were tied up at Lee's Ferry. A few days

were spent there to check over our boats and supplies before starting

the last leg of the journey. Regardless of the record made so far, the

steadily dropping river made the 333 rapid-filled miles of Marble and

Grand Canyons between us and Boulder Dam seem seriously formidable.

August 4th -- The river was too low for satisfactory

navigating, but I gave the word to shove off with the hope that summer

storms in the headwaters would provide a bit of extra water. We soon

passed under the tremendous span of Navajo Bridge, and we were thrilled

by its spider-like beauty, literally hung in the sky. And 8 miles from

Lee's Ferry brought us to Badger Creek Rapid. I lined this one on my

high water trip, and it looked bad this time. But the next morning we

were up early, and after looking the rapid over again I ran all three of

the boats through.

The 61-1/2 miles of Marble Canyon afford wonderful

experience. There are plenty of thrills in the numerous heavy rapids.

But the beauty spots hold the stage -- multicolored marble walls, caves,

arches, springs, and cliff dwellings. The trip through this section is

one of the highlights of the whole river route. I have been in this

canyon with persons who couldn't swim, yet they never felt fear; only a

constant growing wonder at the varying and interesting points of scenic

interest. Beauty certainly lies in the eyes of the beholder, and this

and the other canyons have a knack of presenting a perfect galaxy of

scenery so that all will be pleased.

Passing the Little Colorado River, we entered the

Grand Canyon. The first afternoon we explored some old copper mine

tunnels; then we camped at the foot of Tanner Trail. A big fire was

built that could be seen from the South Rim of Grand Canyon National

Park, and advise of our safe passage to this point.

August 9th -- This marked a day of many thrills and

experiences. The 19 miles from Tanner Trail to Phantom Ranch at Bright

Angel Trail are guarded by some of the most formidable of all the

Colorado River rapids. We ran them all - Hance, Sockdologer, Grapevine,

and dozens of others - and the sight of the suspension bridge marking

Bright Angel Trail was most welcome. Here, under the genial

administrations of our hosts at Phantom Ranch we soon forgot the

hardships involved in handling the boats in such water. A few days saw

us again ready to set off down the river on the last 178 miles

separating us from Lake Mead.

Below Bright Angel, B. W. Deason joined us again, and

Anne Rosner went out. The steadily falling river was making navigation

increasingly difficult. But our concern over navigation was secondary to

our appreciation and enjoyment of the great majestic beauty of this

immense gorge. The sections of granite are particularly beautiful, as

they are shot through with color. We had no difficulty in finding

excellent camping places. As a rule our camps were made at the mouth of

a canyon where there would be a crystal clear stream of excellent

drinking water.

As we wound 'round bend after bend, getting ever

closer to Lake Mead, our anticipation in getting back to civilization

and relatives was considerably dimmed by the realization that probably

the greatest adventure in our lives was soon to be over. All of us had

experienced a trip that was unique and wonderful. We disliked the

thought of returning to humdrum ways. My good friend Harry Aleson, and

his companion, Louis West, met us at Separation Canyon. Their boat got

loose so we formed a rescue crew. The following day, after some steady

rowing, we rescued the boat. Separation Canyon marked the end of our

rapids, and it is surely a fitting and logical point to mark the head of

Lake Mead. Here in 1869 three members of Major Powell's crew attempted

to get outside by climbing up to the North Rim. They were met at the top

and killed by Indians.

In token to the courage and fortitude of Doris

Nevills and Mildred Baker, the first women to make this 1,100-mile trip

through the canyons of the Green and Colorado Rivers, the National Park

Service had a big boat, with some of our relatives, meet us at the head

of navigation. Our hearts were full with the sense of a great

accomplishment, and the pleasure of again being with relatives and

friends. To the several Divisions of the National Park Service whose

interest and help contributed so much in solving many of our problems, I

hereby express for myself and party our sincere and grateful

appreciation.

National Park Service Areas in Region III.

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

|