|

BEAVER ALONG THE SHENANDOAH

By Otis B. Taylor,

Associate Wildlife Technician.

|

Within the last few years much interest has been

manifested in reestablishing beaver in Virginia. Successful efforts in

restocking have encouraged research in order to determine the former

status. The earliest explorers who traveled through the wilderness now

included in the Shenandoah National Park, and through the fertile valley

beyond, usually mentioned seeing beaver along the streams that form a

part of the watershed of the park. In consideration of the known fact

that beaver utilize all habitable streams, it may be assumed they

established themselves within the present boundary of the park. John

Lederer is credited with being the first European to reach the Blue

Ridge Mountains. In The Discoveries of John Lederer, In Three Several

Marches from Virginia to the West of Carolina and other parts of the

Continent: Begun in March 1669 and ended in September 1670, the

author states that on his first expedition from "The Head of the

Pamaeonock, alias York River, to the Apalataeon Mountains,---great herds

of red and fallow deer I daily saw feeding; and on the hill-sides, bears

crashing mast like swine.---Beavers and otters I met with on every

stream." Traveling westward from the York River, Lederer is believed to

have ascended the Blue Ridge Mountains within the present Shenandoah

National Park.

The park includes a portion of Augusta and

Rappahannock Counties. The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography

mentions the occurrence of beaver in the former county. In Volume 30,

page 179, we find the following comment:

"Early suit records of Augusta County, Virginia, show

that wolves, deer and elks abounded in the valley, also the beaver, and

the black fox, and for many years, the skins and furs of these animals

was the source of a considerable revenue. This continued until after the

Revolution, and the valley was visited regularly by traders from

Pennsylvania who came to purchase skins and furs. The fact that a

buffalo hide was worth only 33-1/3¢ in 1730, shows how plentiful

the buffalo abounded in the valley."

Tyler's Quarterly Magazine, Volume 1, page 42,

published the following comment on the "District of Rappahannock":

"The following is a summary of a report of Charles

Heilson, of the Duties received on the Exportation of Skins and Furs

within the district of Rappahannock from the 25th. October 1764 to the

25th of April 1769, to the College of William and Mary.---These ships

exported within the time mentioned 2250 buckskins, 4497 doe skins, 69

pds of beaver skins, 112 otter skins, 54 wildcat, 120 mink, 708 fox

skins, 1371 racoon skins, 171 muskrat and 15 elk."

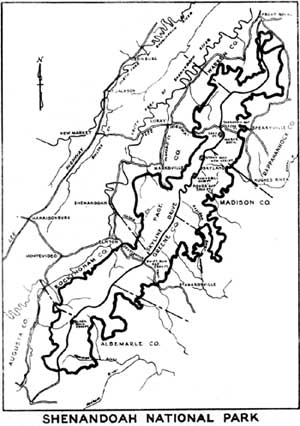

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

|

The reference to Rappahannock District may be

construed to mean a portion of land now included in Rappahannock County,

although this is by no means conclusive. The county was formed from

Culpepper County in 1833, taking its name from the river which forms a

part of its boundary. Rappahannock River received its name from an

Indian tribe which lived along its course.

Samuel Kercheval's History of the valley of Virginia,

Fourth Edition, 1925, states on page 30 that the settlement in the

valley commenced about 1734 or 1735. His comment on the status of beaver

and other wildlife is included, due to the proximity of Shenandoah River

to the park. Kercheval said:

"Much the greater part of the country between what is

called the Little North Mountain and the Shenandoah River, at the first

settling of the valley was one vast prairie and like the rich prairies

of the west, afforded the finest possible pasturage for wild animals.

The country abounded in the larger kinds of game. The buffalo, elk,

deer, bear, panther, wild cat, wolf, fox, beaver, otter, and all other

kinds of animals, wild fowl, etc., common to forest countries, were

abundantly plenty."

Note: "These prairies had an artificial cause. At the

close of each hunting season the Indian fired the open ground, and thus

kept it from reverting to woodland. This was done to attract the

buffalo, an animal that shuns the forest. The progressive deforesting of

the lowlands of the valley made the settlement by the whites very easy

and rapid.

Restoring beaver accomplishes much more than merely

reintroducing an animal that builds dams and houses. Their ponds are

used by waterfowl, wading birds, blackbirds, amphibians, reptiles,

mammals depending upon impounded water, numerous insects and

water-tolerant vegetation The resultant community is unique. In the

course of time the food supply of the beaver may become exhausted. It

seeks a new home and develops a new biological environment favorable for

other animals and aquatic plants. The abandoned pond eventually develops

into a low meadow where the trees upon which the beaver exists again

become established and to which the beaver may return. An orderly

succession is developed whereby beaver becomes the benefactor of many

wild creatures and provides an immeasureable interest for man.

Studies conducted by the Service indicate there are

today no beavers of the original stock anywhere within the boundaries of

Shenandoah National Park. A long-time program of restoration is being

launched on a modest scale this season, however, and it is hoped that

eventually the animals will be restored as a part of the park fauna.

|