|

THE APPALACHIAN TRAIL

And the Shenandoah and Great Smokies

BY MYRON H. AVERY

Chairman, The Appalachian Trail Conference

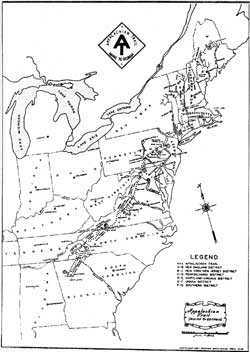

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

|

The Appalachian frail is too well-known a project to

require any extensive elaboration for those who deal, professionally,

with the recreational areas in the eastern Atlantic States under the

jurisdiction of the National Park Service. It is a route for foot

travel, distinguished, it may be said, by its practically endless

character. As it winds its course through fourteen states of the

Atlantic seaboard, it presents a unique opportunity for a study of the

changing zones of botany, geology and kindred sciences - a fascinating

pursuit for even those who observe such features only casually. For

instance, as one traverses the eastern Great Smokies along their

6,000-foot ridge crest, the traveler may well believe himself back again

in the cathedral-like spruce and fir forests of the Maine woods. The

Appalachian Trail Conference and its affiliated groups have also served

as a medium for conveying to the National Park Service their points of

view and suggestions.

But this project, of late, has acquired a deeper

significance. The national parks are in themselves a distinct type of

recreational area. Perhaps to those who forecast and determine the

future of these areas it would seem illogical and unnecessary that still

another type of recreational area should be created within the confines

of a national park. And it would seem all the more extraordinary that

this new type of area should exist for the benefit of a decided

minority. Yet such a development has occurred during the past two years.

The Appalachian Trail in the national parks - and we deal here with the

Shenandoah and Great Smoky Mountains National Parks - has assumed a

unique significance. This is not without importance even in a protected

area such as a national park.

From a mere trail it has become a narrow zone which

has received the status of a protected, insulated area. Here no new

paralleling motor roads are to be built. Where roads are now within a

mile of the Trail and where feasible, the Trail is to be relocated. A

system of simple shelters is to be built along the route. No development

generally imcompatible with the Trail is to be permitted in this zone.

The creation of this status has its genesis in an agreement executed

between the National Park Service and the U. S. Forest Service in

October, 1937. Subsequently thirteen of the fourteen States through

which the Trail route passes have adhered to the Trailway Agreement. The

area affected in the national parks is 159 miles, being divided almost

equally between the Shenandoah and the Great Smoky Mountains. The

significance of this agreement will be appreciated.

I have referred to the agreement as a boon to a

minority but I also view it as a distinct benefit to the National Park

Service. The pressure on the National Park Service to develop further

these two areas is a matter of common knowledge. It perhaps may be

beside the point to overstress their primitive aspect, for much of the

terrain in these two parks had been modified and altered in the course

of the economic development of the eastern United States. However, given

protection and with the benefit of trained and far-seeing planning,

these regions bid fair to revert to the primeval and become an

indication of the type of land that our forefathers knew. Pressure on

the Service for development will be ever-present. The ridge crest of

these areas is particularly susceptible. It will be readily understood

that the Trailway Agreement thus affords a medium for the preservation

of the existing status. While these agreements are not as unchanging as

the laws of the Medes and Persians in that they can be abrogated by six

months' notice, they do represent a distinct declaration of policy and

it may be presumed that neither the Service nor any state will reverse

its policy in this connection without overwhelmingly valid

considerations.

The effect of the Trailway Agreement on the future of

the ridge crest sections of these parks may be noted here. The Skyline

Drive in the Shenandoah National Park is an accomplished fact. In some

sections, by accident of terrain, the Trail and the Drive are in a

proximity which could be avoided now only by dropping the Trail an

undesirably long way down the mountain crest. Therefore, in the

Shenandoah National Park, where the situation was fixed when the

Trailway Agreement came into effect, no major change of route in the

Trail appears to be of advantage at the present moment.

The situation in the Great Smokies is quite

otherwise. This agreement is a shield which the Service may find of

advantage in resisting pressure for further road development along the

ridge crest of the Great Smokies. The agreement is, moreover, of

distinct value as a manifestation of the policy of the Service. It

should be recognized as such by those who declare themselves to be

vitally concerned with the preservation of the primeval and primitive.

The significance of this agreement and its effect, as long as it remains

unaltered, should be thoroughly appreciated. For its policy in this

connection the Service should receive due credit.

The existence of the Appalachian Trail has also been

of value in the development of these parks. It has brought to the

Service the view point of the users of these trails. A trail is

completed, physically, when, shall we say, the CCC detachment has

finished the grading. It is then, however, far from a usable thing. It

requires a definite system of signs; it must be mapped; essential

guidebook description must be prepared to induce its use. Further - and

this is of importance - a system of shelters, having due regard to the

practical situation, must be built. This is a matter of very real

concern in a region such as the Great Smokies where torrential rains are

experienced. The technician dealing with his specialty may not

appreciate all these essentials.

A TYPICAL LEAN-TO ON THE APPALACHIAN TRAIL

Thus, a well-planned shelter from an architectural

point of view often leaves much to be desired from the practical point

of view of the shelter user. In addition, the through Trail, which we

may regard as the master trail in each park, needs to be fitted in and

coordinated with the route to the north and south, outside of the park

boundaries. Private land ownership on each side of the park may produce

an anomalous situation of a trail ending, practically, nowhere.

Much progress has been made along these lines. We

note the situation in the Great Smokies. Since the problems have been

intensively pursued by the Conference after its meeting at Gatlinburg

some two years ago, eight lean-tos along the 62 miles of Appalachian

Trail here have come into existence. These are at intervals of an easy

day's journey for the traveler who would devote more time to the rewards

of his route. For the traveler who moves at a faster pace, the device of

"skipping" a lean-to meets his requirements. We are told that signs,

adequately designating the junction of all side trails and the main

Trail, have been installed for two-thirds of the Great Smokies. A more

reliable maintenance program for Western Smoky - where the Trail is

marked by paint blazes and an unworked footway - bids fair to care for

the problems reported here of inadequate Trail maintenance. A trail of

the type that exists in Western Smoky requires, of course, far more

frequent attention than the graded type where the route is

unmistakable.

While the Shenandoah is forced to yield the palm to

the Great Smokies as far as the lean-to situation is concerned, its

trail system, regarding the Appalachian Trail as the trunk line from

which side trails radiate to points of interest, has reached a stage

near completion. With the cooperation of the Potomac Appalachian Trail

Club, this park has carried out a systematic program of trail signing.

Maintenance problems are being systematically cared for. In addition to

five closed shelters available along its route, the open lean-tos for

the north half of the park, accessible to all comers, will have been

completed by the spring of 1940. The next year should see this chain

well toward completion.

I have emphasized that this recreational area of The

Appalachian Trailway is for a minority interest. Those who camp, walk

and seek their own recreation on foot represent a decided minority.

Perhaps at times their presence and views have been considered not an

unmixed blessing. Certainly, in terms of representation and use, the

cost of the construction of these trails (albeit a lower standard might

well serve the purpose) is disproportionate with the cost of highway

construction. This theory, of course, carried to its logical conclusion,

would overrun the national parks with roads. Trails, their users, and a

trail system may therefore, well be regarded as a means of defense

against over-development. As such trails and trail development are an

essential and an integral part of our park system, their existence is

justified on grounds of proper planning and use and not by a census of

the number of trail users and automobile riders, respectively. It is

perhaps well to appreciate this factor and evaluate it. At times,

emphasis on this comparison and insufficient use of trails (statistics

entirely correct in themselves), emanating from the officials in charge

of these areas, may unwittingly tend to create the impression that the

roads and kindred appurtenances are, in their view, the only

developments which justify the expenditure and activity involved. Such

an impression is indeed an unfortunate one to be abroad, for it can form

the basis of unfair and improper criticism of the Service policy. To

this end, the Trailway Agreement, as representing a distinct boon to

what we must admit without question is a decided minority, forms a very

useful answer of a recognition of the part that trails and trail systems

play in contrast with overdevelopment.

View from the Appalachian Trail in Great Smoky Mountains

National Park.

|

Perhaps when pursued to their ultimate conclusion,

these suggestions of inadequate use of any aspect of the recreational

features of the parks except the roads disclose some failure on the part

of the authorities in charge of these areas to appreciate the

practicabilities of the situation. It is not enough to have a trail

(ummapped, unsigned, unrecorded) built to some outstanding feature. It

is essential to have the existence of a route publicized and made known.

The mere completion of the trail will not, ipso facto, insure its use.

Yet one looks in vain for any activity which would publicize or

stimulate the use of these trails in the eastern parks. The Service has

available no maps, no guidebooks or publicity which meets this essential

need. An instance, however, of an approach to the problem is the

large-scale mounted maps being erected by the Landscape Architect along

the Skyline Drive in the Shenandoah National Park where there are trail

connections with the Drive. The outing clubs, as a voluntary

contribution, have picked up where the Service stopped. They have issued

the only maps and guidebooks for the area, and endeavored to stimulate

the use of these facilities through the medium of their publications.

Naturally, the response to this needed publicity manifests itself first

in the membership of those groups and this, curiously, brings the

suggestion that the facilities are being provided, with much expense,

for the benefit of a few organizations. The résumé of this

situation means this. A trail is not to be afflicted with some

apochryphal character. Its building is only the initial step. Granted

that facilities to that end have been inadequate, those who stress

insufficient use of any park facility except the roads must recognize a

failure to complete the job, to put it bluntly. The clubs and the

Conference have endeavored to remedy this deficiency to the extent their

limited resources permit and have to some degree.

A member of the Trail Club applying the type of blaze

used in the western Smokies to indicate a turn.

|

While this résumé is somewhat detailed,

it points to two factors in the situation of controlling importance. The

first is the assurance that the Service, through the Appalachian

Trailway Agreement, holds out to those who fear for the future of the

ridge crest in these areas. The second is that the Trail system - a

recreational feature of the park - through its medium of fitting into

the Appalachian Trailway Agreement, has been brought to a state of near

completion and better utilization than would have occurred had the

matter been pursued independently.

There is a third area under the jurisdiction of the

National Park Service which perhaps can be best summarized by saying

that it presents an outstanding problem to the Appalachian Trail

Conference. Perhaps the least said about the area the better. In any

event, it is a tribute to the original location of the Appalachian Trail

that the route of the Blue Ridge Parkway should be almost squarely

imposed upon it for its entire length of 150 miles. This section along

the curving rim of the Blue Ridge crest in Virginia is a section very

little frequented, inaccessible and somewhat removed from the activities

of maintaining organizations which care for the Trail elsewhere.

Perhaps in the course of economic development which

is manifesting itself here independently of the Blue Ridge Parkway, its

fate might have been sealed anyway. What relocations can now be made to

advantage are being made at the present time. For the most part, the

Trail parallels the Parkway. Ultimately, it is planned to make the last

major change in the Appalachian Trail route by shifting this section far

to the west through the publicly owned lands in western Virginia, which

afford a possibility not available at the time the Trail route was

originally projected.

This résumé of the development of the

Appalachian Trail in the areas under the jurisdiction of the National

Park Service is perhaps well made at this time to make clear the

situation to all those interested in these regions. Its primary

significance as a "Maginot Line" to those who fear overdevelopment and

as the perfection of a "finished" trail system seems at the moment - if

one's vision of the forest is not too much clouded by the presence of

the trees - to be outstanding. Perhaps it will also not be without

future significance.

|