|

Rocky Mountain National Park A History |

|

|

Chapter 1: TALES, TRAILS, AND TRIBES

WHEN HISTORY is not written, humans speculate about the past. It takes quite an imagination to envision the first human visitors tramping into the vast mountain chains of the American West. And so far no one has discovered the names of the first people who walked into a small segment of these mountains later to be named Rocky Mountain National Park. One might wonder what these early travelers looked like. Were they properly attired for their outing? What was their purpose in exploring such a rugged region? Were they wandering around in a search for good hunting or fishing? Did they appreciate the scenery? Did they stay long? Or did they travel through quickly, merely taking an adventurous break from otherwise humdrum lives? Written historical accounts offer few answers. Questions about these unnamed travelers continue to tax the minds of today's scholars. Geologists have examined the mountains and have provided timetables that cover thousands of years, allowing for the construction of nature's wonders, detailing the movements of glaciers, discovering when lakes, streams, and valleys were formed. Listening and recording, ethnologists asked elderly Indians to recall their youthful travels and, as a result, some thoughtful memories and legends were gathered for our consideration. Meanwhile, exacting historians, expecting to find written documents or eyewitness accounts for evidence, could only offer names of nineteenth century travelers and settlers who claimed to be the region's first visitors. But now all those pioneers are recognized as relative newcomers in the history of this area. For when it comes to identifying Rocky's first hikers, fishermen, and hunters, facts are scarce.

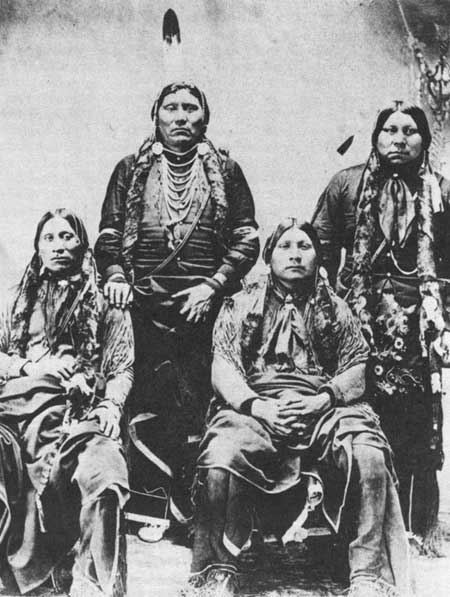

Those who paint the most believable portraits of this vague and early segment of our historical profile are members of the most recent generation of archeologists. Painstakingly reconstructing the past, archeologists examine artifacts ranging from stone projectile points and knife blades to ill-formed granite chips. Results of their studies now make it certain that man has been entering these mountainous regions for thousands of years. The first studies were of native Americans who ranged throughout Colorado during the nineteenth century, principally the Utes and the Arapahos. Early settlers spotted these tribes in the neighborhood, and at one time the federal government recognized their claims to this territory. No one doubted that they frequented Estes Park, Grand Lake, or the mountains in between, for they left some well-worn trails, a few pine pole wickiups, bits of pottery, and some lost or discarded hunting equipment and tools. The Ute and Arapaho tribes also left some intriguing stories about events occurring here, either factual or fancied, recalled from memory and legend. Building on that information and inspired by significant archeological discoveries on the nearby Great Plains during the 1920s and 30s, both amateur and professional archeologists started recognizing artifacts that could be dated much farther back into the dim past. While scholars may never validate an Indian tale regarding an act of creation, they have enabled our examination of Rocky Mountain National Park's human past to begin some ten to fifteen thousand years ago. It is now understood that migrating people arrived on the Great Plains of North America after crossing from Asia during the final stages of the Pleistocene or Ice Age. Only when the great continental ice caps began melting were nomadic hunters able to work their way southeastward from Alaska. Archeologists now assume that aboriginal entry into North America became possible by movement through an ice free corridor located between the massive ice cap and the glacier-filled Rocky Mountain ranges anytime between thirty thousand and ten thousand years ago. This early era of human activity has been termed the Lithic stage, referring to the use of stone as a primary source for tools and weapons. Gradually these people moved southward, perhaps taking decades to migrate. Their lives depended upon hunting, particularly in stalking herds of the now extinct mammoth. Out on the plains, only thirty-five miles due east of the Park at the Dent archeological site, twelve of these mammoth remains have been discovered. Crafted stone Clovis projectile points, clearly in association with those skeletons, allowed scientists to refer to these early inhabitants as "the elephant hunters of the West." [2] Using radiocarbon dating procedures, archeologists found this kill site to be eleven to twelve thousand years old. Called Paleo-Indians or Early Man, these people co-existed with now extinct megafauna or large mammals. As the earliest ancestors of tribes known to history, they undoubtedly hunted within this general region as the great continental ice sheets continued to recede northward. At least four carefully crafted Clovis and Folsom projectile points located in Rocky Mountain National Park correspond with this earliest arrival of hunters. Finding some of this evidence on Trail Ridge, one archeologist argued that even these few clues gave proof of people crossing the mountains sometime between ten thousand and fifteen thousand years ago. He did concede that later Indians might have transported these early points into the Park, but patination, or weathered "varnish" upon these stone points helped testify to their longevity at their alpine resting spots. Such scanty evidence, however, led the researcher to conclude "that this environment held little interest for peoples adapted to hunting the mammoth and the bison." [3] Nevertheless, discovery of these ancient projectile points, as well as dozens of a more recent age, showed Trail Ridge to be a usable east-west route for crossing the mountains soon after hunters inhabited the plains nearby. While wandering mammoth and bison hunters may have strayed across the mountains, no evidence suggests that they stayed. Periodic trips through the Park, while heading for better hunting grounds, may have been the rule for hundreds of years. Gradually, perhaps as a result of a warming, drier climate, the mammoths disappeared from the Great Plains and became extinct. Whether hunted into extinction by the Paleo-Indians (as some Scientists believe) or merely unable to adapt to a drier, warmer climate, no one knows for sure. But Early Man, meanwhile, adapted to that loss. Those people merely changed their appetites and targets, now selecting the superbison as their primary quarry.

Only forty miles northeast of Rocky Mountain National Park archeologists have located the famous Lindenmeier site, an ancient Folsom camping spot used repeatedly some eleven thousand years ago. The bison Antiquus, now also extinct, was hunted there. It was larger than the modern bison by twenty percent and had horns at least twice as large. Depending upon that animal as a primary food supply, bands of Paleo-Indians followed the herds, camping in such spots as Lindenmeier Valley, possibly exploiting seasonal fruits, nuts, and grass seeds to supplement their diets. They probably moved their camps from fifty to a hundred times each year. Without question these hunters were skilled at survival and understood well how best to exploit the natural resources around them. They also devised new hunting techniques, perfecting group or communal drives or attacks as they surrounded their hoofed meals. It also seems likely that these hunters developed a great familiarity with the land over which they roamed, becoming aware of every usable animal or plant. Hunting for unusual animals in unfamiliar territory could leave a person quite hungry. Certainly these people could predict the behavior of animals they hunted and knew when and where wild crops were ready for harvest.

The basic lifestyle of these nomadic hunters probably changed very little over several thousand years. Their shelters were merely animal hide tents, brush huts, or rock shelters; clothing was made from the skins of animals they butchered; dogs were their only domesticated animal. Over time they changed and refined styles in the manufacture of their stone knife blades, spear points, scrapers, and other equipment. And while making their implements and tools of stone and bone was artistically creative, their art remained primarily utilitarian. Most of the items made were quite disposable, easily refashioned in the trained hands of a Paleo-Indian craftsman. Hundreds of bits of their cast-off equipment became mementos of their ancient presence. Around eight thousand years ago, prehistoric Indians in this region of North America began to display traits of a new lifestyle. They became more exploitive of nature generally, decreasing their dependence upon herds of giant bison. This era, lasting in many ways into the period of written history, has been termed the Archaic stage. Hunting continued, of course, with the smaller modern bison as the key menu item for plains inhabitants. But hunters also became more active in exploiting regions beyond the Great Plains for a greater variety of foodstuffs and other materials. And so the Rocky Mountains began experiencing more visits from this time forward. Even so, use of Rocky Mountain National Park's resources may have been confined to its trails and passes as hunters left the plains and headed for Middle Park. From projectile points located at Forest Canyon Pass, on a slope above Chapin Pass, at Fall River Pass, on Flattop Mountain, near Oldman Mountain, as well as on numerous ridgetops, in valleys, and on mountain saddles, one archeologist concluded: "Evidence indicates intermittent occupation of the Park rather than continuous occupation. Travel back and forth across the Continental Divide was the primary reason why Indians entered the mountains. Small camps indicate seasonal hunting in the valleys and on the mountains." [4] Seasonal hunting, then, attracted Archaic man, just as it would later attract the nineteenth century "discoverer" Joel Estes. But mountain sheep and elk might not have been the only reasons Archaic hunters came to the high country. Significant fluctuations in the climate began to produce a much hotter and drier weather out on the plains. This period, known as the Altithermal, may have lasted for 2,500 years, from 5500 B.C. to 3000 B.C. Some scholars believe that ancient inhabitants left the plains entirely during this period, and may have vacated the Front Range of the Rockies as well. But other studies give evidence of continued use of these moister cooler mountains as refuges from a harsher climate. Evidently man used this area more heavily at this time period. Plants and animals necessary for their survival could be found here in abundance. More than just seasonal refugees, the people adapted. Recent discoveries at alpine sites south of the Park have demonstrated that some camp sites and large game drive systems date between 3850 and 3400 B.C. Even these well-used sites, however, are believed to have been temporary, seasonal camps, with Indians migrating to milder spots during winter. It is suspected that groups of people, primarily extended families, migrated each year from the lower elevations of the foothills up to the high country as seasonal conditions permitted and as wild plants ripened and animals became active. The most intriguing archeological remains from this era are the large stone structures of the game drive systems. Scholars have identified forty-two of these low-walled rock structures at locations along the Front Range crest. They are dry laid stone walls or closely built rock cairns, producing a slight barrier along the natural slopes. Some of these walls may stretch for hundreds of feet in length. One of these structures, for example, lies close to today's Trail Ridge Road. At one time pioneers speculated that these walls were fortifications, used by one tribe to defend its territory against an invader. Today, evidence points toward their use in hunting animals in country devoid of cover. Commonly used in other arctic or tundra environments, these slight walls served as devices that permitted hunters to direct or herd game animals toward men waiting with weapons. Quite a variety of walls were constructed, depending upon the lay of the land. Normally they were built by piling rocks in long rows, forming a perceptible barrier or wall. Sometimes the walls formed a U or V shape or had parallel rows; some also had pits nearby to help conceal an ambushing hunter. It is clear that building these rock-walled drive lines took considerable amounts of time and labor, but it is also assumed that these helpful structures were used repeatedly for centuries.

It is probable that twenty to twenty-five people were needed to conduct an animal hunt of this type, with some Indians driving the mountain sheep or elk toward awaiting hunters poised to kill. Spears tipped with razor sharp stone points, or darts thrown with an atlatl or spear thrower may have been used to kill the animals. Mule deer, mountain sheep, elk, and bison became the primary animals hunted. Black and grizzly bears, pronghorn, and mountain lions might also have been killed on occasion. Smaller animals, hunted at lower elevations near the seasonal camping spots and in other lower valleys, also augmented the ancient diet. These animals may have included wolves, coyote, beaver, porcupine, foxes, marmots, skunks, racoons, rabbits, squirrels, and other small birds and game. Hunting smaller mountain animals did mean that the hunters' quarry yielded far less meat than a typical superbison or even the modern bison. That meant that more animals had to be killed to provide the same amount of meat. So eating a wider variety of smaller game and also locating numerous edible plants and berries became a way of life. Indians harvested blueberries, raspberries, creeping wintergreen berries, Colorado currants, and many others. Their potherbs included fern-leafed lovage, fireweed, marsh marigold, and alpine sorrel. Roots dug, cooked, and eaten included American bistort and alpine spring beauty. In addition, dozens of other plants and animals found at different elevations from the foothills to the alpine regions were probably a part of their ancient menu. By the time the Altithermal ended and mankind repopulated the plains, these people could no longer be classified as merely hunters; rather, they had become foragers. Upon their return to the prairie, bison hunting regained its importance in their lives as one could expect, considering that a thousand pounds of meat would be available to a hunter from killing just one of these animals. Middle Park and the Great Plains once again returned to the center of ancient hunting activities. And those regions would remain primary hunting grounds into our historic era. Though now more flexible in their diets, these ancestors of the historic tribes depended upon bison; yet they could also return seasonally to hunt in the mountains as well. An abundance of archeological material, ranging from fire pits to grinding stones to tools to bits of burned bone, as well as hundreds of stone chips left from tool-making, gives ample proof of recurrent visitation to this region from 2500 B.C. onward. Between A.D. 400 and 650, the technological innovation of the bow and arrow was introduced. Perhaps brought into the region by Woodland Culture moving in from the east and the Colorado plains, remains of that equipment in the form of small, serrated, and corner-notched arrowpoints are found in considerable numbers throughout the Park. In addition, the first traces of pottery sherds can be dated from this era. It is possible that tribes known to history, Shoshoni or Ute, may have finally laid claim to these mountains and to the hunting grounds on either side. And for a while at least, between A.D. 650 and 1000, game-drive systems continued to be used.

Abner Sprague, one of the original settlers of the 1870s, remarked: "That the Indians made Estes Park a summer resort there is no question, as evidence of their summer camps were everywhere throughout the Park when the White pioneer came." Whether those old camps were Shoshoni or Ute, Arapaho or Apache, Sprague did not clarify and perhaps could not tell. But he did add: "There was no sign of permanent camp, such as a winter stopping place would have to be for them to live in comfort at these altitudes. . . ." [5] Judging from the observations of men such as Sprague as well as earlier explorers, such tribes as the Ute and Shoshoni probably laid the longest and strongest claims to these mountains through their occasional summer visits. Exactly when the Utes came into Colorado, along with their allies the Shoshonis and the Comanches continues to be an issue debated among ethnologists, anthropologists, and historians. Even where these Native Americans originated is in doubt. Perhaps they had migrated from the Great Basin or further southwest or from Mexico. Some scholars suggest that these tribes are simply the descendents of the earlier Paleo-Indian and Archaic peoples of the region. They may have emerged from the hunting-gathering Desert Culture identified farther west. The language of the Utes and their allies was similar, based in Shoshonean. Whatever their origins, it is now suspected that these people gradually invaded and dominated Colorado's three large western slope parks—South, Middle, and North—as well as its mountains sometime about a thousand years ago.

The Utes have been termed "central based wanderers" since they did not rely upon agriculture and had to travel to hunt or gather their food. Winter might find several families camped together, but springtime would start small bands on familiar trails toward hunting grounds, berry patches, or the like. Small family units hunted together, living off land that could not support large populations. They stalked deer or antelope or snared jackrabbits. They also dug roots and picked berries when those items became available. Their shelters consisted of both bison-hide tipis and brush-covered wickiups. Permanent dwellings were unnecessary since these people were nomadic. Their quest for food tended to separate the Utes into several bands during most of the year. Many families also separated from the bands to hunt or forage on their own. While food was not abundant, studies indicate that these people were probably not preoccupied by an endless task of food acquisition. Scholars do believe, however, that all bands of Utes knew times of great hunger.

There is some evidence that springtime brought an assembly of all the Ute bands for a tribal Bear Dance. The Utes, like other tribes in the mountain West, respected and honored those ursine competitors for the annual berry crop. The Bear Dance also provided some social contact for a people forced to forage alone and in relative isolation. Within this social and economic context, spots like Middle Park and Estes Park, similar to other valleys in the Colorado Rockies, may have served families of Ute, Shoshoni, or Comanche hunters for season after season over hundreds of years. The Utes, in particular, entered the pages of recorded history when they finally met the Spanish. By the early 1600s, Spanish explorers had pushed their way out of Mexico toward Colorado; prospectors and missionaries followed in their wake, working gradually northward. Eventually they encountered the Ute people. Although Spanish documents do not refer to the "Yutas" until 1680, it is probable that trade started prior to that date. The Utes began exchanging meat and hides for agricultural produce. They also began buying horses. High prices for such valued animals proved to be no deterrent to trade whatsoever and it was reported that they "started trading their children for horses." [6] Horses revolutionized the Ute lifestyle, just as they had that of Ute neighbors the Shoshoni and Comanche. Mobility was the key to change. By the early 1700s, combined forces of mounted Ute and Comanche warriors came raiding out of the mountains attacking the homes of plains-dwelling Apaches who were then living in eastern Colorado. Raids also began against Spanish settlements in New Mexico and continued sporadically until a treaty was finally negotiated with Spanish officials in 1789. But horses not only brought mobility and aggressive attacks; they also transformed the Utes into skillful bison hunters. Hunting trips onto the eastern plains meant that the buffalo soon became the Utes' "chief economic resource, providing tepee covers, blankets, sinew thread, bowstrings, horn glue, skin bags, moccasins, and meat in greater quantities than the Utes had ever known." [7] Bison meat could also be dried, reducing its weight by ten times, and then easily transported and stored for months. About one-half pound of this highly concentrated dried meat could serve as an adequate daily ration for an adult. Anthropologist George Frison clarified: "The flesh from two full-grown adult bison or twenty antelope would dry into about 100 pounds. This quantity has the potential to sustain a family group of six persons for about a month, which would tide the family over critical times during most winters." [8] Eventually the Utes and their Comanche comrades had a falling out. In 1748 a fight developed between these two aggressive tribes. It is supposed that the alliance between them was not very strong to begin with, and was certainly further aggravated when the Comanches obtained firearms from French traders who had entered the plains by this time. By 1755 the Utes had been forced to retreat back to the western slope of the Rockies. And there they remained, reasonably well protected throughout the next century. They did return to hunt on the Great Plains once or twice each year, but they tended to remain within the protective shadow of the Rockies. It was during this era of war-making and hunting that the Utes probably traveled across Rocky Mountain National Park's east-west trails. Trail Ridge, Flattop Mountain, and the Fall River routes were probably used, with Forest Canyon and its Pass an obvious pathway. Certainly the Ute tribe and other Indians were not confined just to these trails; many other passes, saddles, and canyons could have been used to cross the Front Range, and several were far more popular than those in Rocky Mountain National Park.

So within a few decades horse power had transformed Ute society. Of course certain aspects of their older way of life endured. Food gathering, for example, continued as usual and their diets remained diverse. Ute women continued to seek chokecherries, sunflower seeds, and various other edible roots and grass seeds. They also constructed willow weirs and caught fish, adding variety to their meals. The men continued to hunt mule deer and antelope, even though the bison was preferred. Any changes in their food supply were small when compared with the transformation of the Ute political and social structure. The horse allowed war-making to play a major role in their lives. Larger bands took the place of single families as the primary living unit, especially since numbers insured protection when enemies made retaliatory raids. When proceeding onto the plains for a bison hunt, several hundred Utes might join together for the expedition. War leaders also became far more important. Their influence also extended into other matters within Ute society, creating the basis of a political framework. Eventually seven major divisions or bands among the Ute evolved. Those living in the southern part of Colorado were the Weeminuche, the Mouache, and the Capote. Living in the west-central region were the Tabeguache or Uncompahgre. And three groups comprised the Northern Utes, namely the Grand River, the Yampa, and the Uinta bands. Estimates of their total population vary anywhere from 2,500 to 10,000 people. In 1875 the Commission of Indian Affairs listed 40 bands of Ute with a total of 9,625 persons. Whatever their number, the 1700s saw them at the height of their power. Historian Wilson Rockwell concluded that the eighteenth century "marked the zenith of Ute strength and glory." [9] Their century of glory and aggression was quickly tempered by the arrival of the Arapahos around 1790. Migrating from the Red River and Manitoba country far to the northeast, the Arapaho people were probably pressured into moving late in the seventeenth century due to constant attacks from the Assiniboin and Cree. Within a few generations, they had adapted to using horses, hunting bison, and gaining all the general characteristics of a Plains Indian culture. Eventually they moved across the Missouri River, entered the Black Hills region, and used the hunting territory of the upper Great Plains. Only a few decades later, however, during the 1780s, the Arapaho were attacked by the expansionist Sioux who came from the east. That pressure forced the Arapahos and their allies the Kiowa and Cheyenne to move farther south, eventually into the South Platte country adjacent to the Front Range of the Colorado Rockies. There, for a reason unknown to us, they began a continuous war with the Utes.

These Arapaho invaders were given a variety of names. The Shoshoni and Comanches called them "Saretika" or Dog Eaters as a comment upon one of their prized menu items. They were also called the Bison Path People, the Tattooed Breasts, and the Big Nose People, depending upon which characteristic caught the eye of the name-givers. The Pawnee called them "larapihu" or "tirapihu," meaning buyer or trader. Thus derived from their skill at trading, the name Arapaho—variously spelled—seemed to stick. The Arapaho called themselves "Inunaina," or simply "Our People." [10] Not long after entering the Great Plains the Arapaho separated into two major divisions, the Arapaho proper and the Gros Ventre. The Gros Ventre split off, migrated northward, and roamed the northern side of the Missouri River in Montana. The remaining Arapaho began traveling south and west. The Arapaho were subdivided into four bands, sometimes named the Long Leg or Antelope, the Greasy Face, the Quick-to-Anger, and the Beaver. Band names, like those of individuals, changed frequently. Each band had a chief and a council of the four chiefs made major decisions in concert and consensus. The Arapaho were not numerous, with their population probably never exceeding 2,500 persons. But their impact upon the Colorado region was greater than their numbers might indicate. Although they considered eastern Colorado their heartland, they were nomads and roamed a vast region of the plains and mountains. They hunted and raided nearly every square mile from the Wind River Mountains of Wyoming clear down to the Arkansas River valley in southern Colorado. Their movement and aggressiveness found them fighting the Crow Indians to the north, the Pawnees to the east, and the Utes and Shoshonis across the mountains to the west.

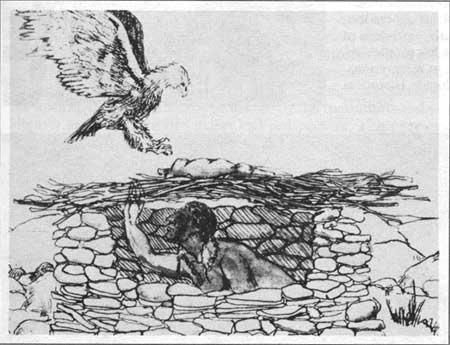

Living on the Great Plains over the period of several generations, the Arapaho became the apex of mobile, nomadic hunters. They excelled at horse riding; they were skilled at hunting bison, using the technique of driving herds off sharp-edged cliffs. These "buffalo jumps" allowed the Arapaho to turn a mass slaughter into a vast butchering site. Working upon the slain animals, the Arapaho could obtain hides for their tepees, bone for their tools, sinew for their thread, leather for their clothing, and food for their stomachs. Arapaho life centered around the hunt. And, at the beginning of the nineteenth century, the plains and mountains of Colorado supplied an abundance of their quarry. But it is probably their invasion of hunting grounds traditionally used by the Utes that brought them into a conflict with those older residents. Historian Virginia Trenholm reported an Arapaho belief that the "Man-Above created the Rockies as a barrier to separate them from the Shoshonis and Utes." [11] Clashes between those tribes were numerous and sparked the stuff of legend. Memories of this continual tribal conflict are a part of Rocky Mountain National Park's heritage. The very thought of Indian fighting Indian, of bloody battlegrounds, seemed to enchant early settlers who watched Indians become relegated to reservations. Yet tangible evidence and reliable accounts of most of those battles do not exist. Some of the tales are nevertheless intriguing. A story often repeated tells of a band of Utes peacefully camping at Grand Lake. Some Arapaho warriors with their Cheyenne allies crossed Willow Creek (Forest Canyon) Pass with an eye toward mischief. Ute scouts failed to spot the invaders and a surprise attack resulted. During the raging battle that followed, an effort was made to protect women and children by putting them upon a makeshift raft and sending it out upon the lake. As the fighting continued no one seemed to notice that a strong wind began blowing, ripping the raft apart, and drowning all of the women and children. The Utes won their battle, drove the attackers away, but then realized that they had lost their families. From that point forward, it was said, the Utes avoided Grand Lake because it was haunted by the spirits of those who had died there. There could be important elements of truth in this tale, but it might also be mere wishful thinking on the part of settlers who hoped the Utes would not return. They preferred the legend over the reality of worrying about being attacked. East of the Divide, early settler Abner Sprague commented that "it is well established that conflicts between tribes took place in the (Estes) Park." He did not explain whether artifacts, bones, or hearsay provided a basis for that "fact." But he did clarify the location: "One battle ground being located without question, Beaver Park and the Moraine between there and Moraine Park. There is the ruins of a fortified mound at the west end of Beaver Park, where the weaker party made their last stand." [12] Were these "ruins" really an Indian fort, or in reality a game drive system? The truth may never be known. One of the few eyewitness accounts regarding an actual fight came from Charles S. Strobie. In 1865 he was twenty years old and had just traveled across the plains from Chicago, forced to fight Indians along the way. He reported crossing "the Snowy Range by way of Berthoud Pass" in 1866 and living with Nevava's band of Utes "who were hostile to the plains Indians." Then he recalled: "I was the only white man with the Ute 'war party' when we had a fight with the Arapahoe and Cheyennes in Middle Park, near Grand Lake. We repulsed them and took seven scalps. Others were killed or wounded, but they were thrown across the ponies' backs and carried off." The victorious Utes, with Strobie tagging along, returned to their main camp near Hot Sulphur Springs where "we had scalp dances and parades every forenoon and night for two weeks." [13] Using Rocky Mountain National Park's passes and trails to catch enemies by surprise or to find better hunting grounds gave both the Utes and the Arapahos cause to enter this region. Other activities occurring in these mountains were probably less dramatic. One lesser known attraction, that of trapping eagles, may have drawn solitary Indians toward these peaks. It was common for Indians to seek high country locations, conceal themselves in a brush covered pit, and lure eagles toward a hunk of meat placed as bait upon the brush. Ethnologist Alfred Kroeber explained: "Only certain men could hunt the eagle. For four days they abstained from food and water. They put medicine on their hands. In four days they might get fifty or a hundred eagles. A stuffed coyote-skin was sometimes set near the bait." [14] Whether the summit of Longs Peak was actually used as an eagle trap, as later Arapaho informants claimed, cannot be verified. The first recorded climbers found no evidence of any pit or other traces of human activity when they arrived at the top of Longs Peak in 1868. Yet other mountains or high country ridges might well have been used for snaring eagles, creatures considered so valuable because of their decorative feathers.

Tales of trapping eagles on Longs Peak may sound improbable, but may not be as fanciful as a few other reported exploits. One example, told by an Arapaho, Gun Griswold, about his father Old Man Gun, detailed a bear hunting technique. Griswold recalled: "He used to daub himself all over with mud and lie down in the bear trail. A bear would come along and not know what to make of him, turn him over with his paw, feel his heart and his mouth. All at once Gun would spring up and give a terrible yell. The bear would jump back so quickly that he would break his back." [15] Today's fishermen who enjoy telling tall tales about "the one that got away" may find a nodding kinship with that remarkable hunter.

All the Indian claims upon these mountains, fought over for decades, were doomed to be quickly extinguished. The discovery of gold in Colorado brought thousands of prospectors and miners flooding into the territory after 1858. Most promises made to either the Ute or the Arapaho regarding their rights to this land underwent speedy revisions as the white population increased. According to the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851, territory of the Arapaho stretched between the North Platte and Arkansas Rivers, from the Continental Divide of the Rockies eastward onto the plains of Nebraska and Kansas. Only a decade later, through the Fort Wise Treaty of 1861, the federal government hoped to confine these wanderers to the much smaller Sand Creek Reservation located along the Arkansas River. In 1865 another reservation was chosen in southern Kansas and northern Oklahoma. And by 1878, the Arapaho had finally been removed from Colorado entirely, some living on the Wind River Reservation in Wyoming while others lived upon the Cheyenne and Arapaho Reservation in Oklahoma. The Utes lost their claims a little later, although just as rapidly. For a while they seemed to be protected by the mountains and were slightly more tolerant of settlers and prospectors. Their presence was not regarded as bothersome to the new invaders until later in the 1870s. Historian Robert Black noted that "often they were overlooked, which was the supreme insult." He added that "the average prospector or pioneer rancher had few objections to aboriginal comings and goings, but when certain Utes began to treat [Middle Park] as their own, slaughtering game, violating fences, and terrorizing housewives, there were vigorous complaints." [16] Earlier in the 1860s, treaties had granted the Ute people rights to the western one third of Colorado. But when gold was discovered in the San Juan Mountains Indians were forced to cede that region in 1873. Escalating violent clashes late in the decade led to growing public hatred toward the Indians. Demands for reprisals sealed the Utes' fate; the popular cry became "The Utes must go!" [17] And their fate meant removal from most of Colorado during the 1880s. Only a small strip of land in the southwestern corner of the state and a reservation in Utah would remain within their possession. So, within a generation, any Indian claims upon the area later to be come Rocky Mountain National Park were negotiated away. The Indians' influence in the region remained safely in memories and legends. As the Indians left, settlers of the Grand Lake and Estes Park region expressed a feeling of relief. As with most of Colorado's early pioneers, they preferred to have the Indians carefully confined. A Denver newspaper reflected a popular sentiment: "The great menace to the advancement and development of this grand southwestern country is no more. Eastern people can now come to this section in the most perfect security." [18] Reverend Elkanah Lamb, settler at the base of Longs Peak in the 1870s, expressed an attitude common to the frontier. "The Indians of the plains at that time" he wrote in his memoirs, "were an intolerable nuisance, always visiting our camps to buy, steal, and annoy." [19] His conclusions about "the Red devils" left little room for sympathy: "Seemingly the red man . . . [has] not the capacity or the necessary will-power for the improvement or possible development of nature's grand and prolific resources that are comprised of soils, forests, and mineral fields, and, therefore, it appears to be destined for the white man." [20] When rendered harmless, Indians became a curiosity, if not a source of pride. In 1914, as detailed mapping necessitated more names for mountain peaks and other features, members of the Colorado Mountain Club invited some elderly members of the Arapaho to return to the Estes Park-Grand Lake region. During a two week camping trip through the mountains, Oliver Toll dutifully recorded the words, place-names, stories, and observations of Gun Griswold, age 73, and Sherman Sage, age 63. As a result of their visit, dozens of Indian names were assigned to these mountains. Although half a century had elapsed since these men used the trails, their observations were prized as one last contribution from another culture. Commenting on this "rash of Indian names" suddenly dotting the landscape, Louisa W. Arps and Elinor E. Kingery, nomenclature authorities, stated that "the Rocky Mountain National Park area includes 36 Indian names, not counting names in translation like Gianttrack and Lumpy Ridge and Never Summer. This is one of the greatest concentrations of Indian names in one small area on the face of the U.S.A." [21] Even though the Indians themselves disappeared from the area quickly, mementos of their presence remained. If only in place-names such as Neota Creek, the Ute Trail, or Niwot Ridge, their centuries of traveling through and hunting in this region would be remembered. The bitterness between settlers and Indians over the ownership of this particular stretch of mountains disappeared with time. Some would argue that Indian ties to this region were transitory and shallow anyway; their homes were elsewhere. But perhaps the Indians were simply overwhelmed and became fatalistic; they had little choice but to leave and accept reservations and a new way of life. Some ancient tools and stone structures, some tracks and trails, and some legends stayed to mark their prior use of the land.

A Ute interpretation of the afterlife explains their concept of a final settlement. "Heaven with them is in three great strata," author Hamlin Garland recorded. "In the highest is the Ute spirit land, and all the Utes have wings. In the second are the buffalo and all the game and beautiful forests and meadows. In the lowest strata are the white men." [22] |

| <<< PREVIOUS | CONTENTS | NEXT >>> |

Rocky Mountain National Park: A History ©1997, University Press of Colorado All rights reserved. This text may not be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the University Press of Colorado. buchholtz/chap1.htm—26-Dec-2006 | ||