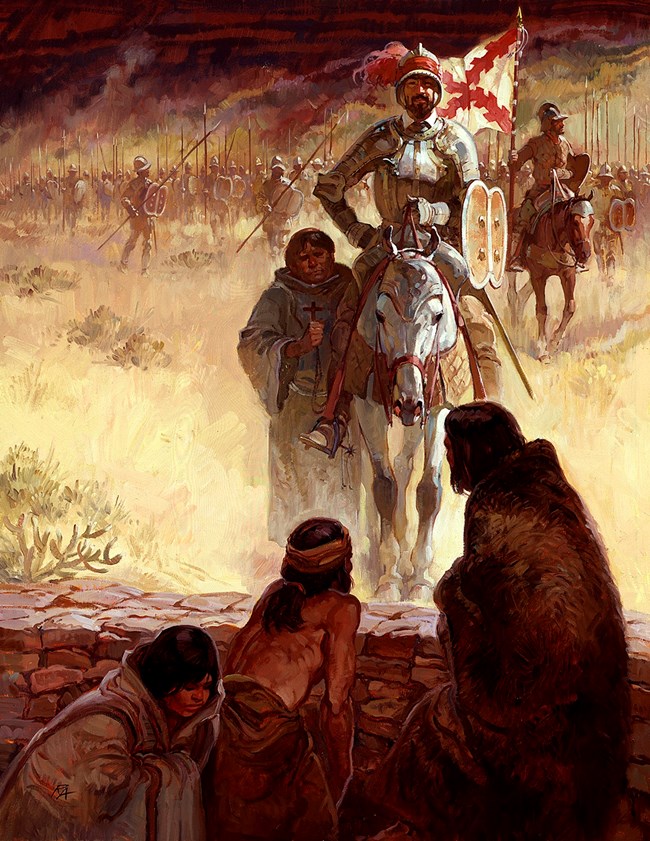

NPS Painting/Roy Andersen Change Comes to P`ǽkilâIn 1540, Francisco Vasquez de Coronado led an expedition to establish a new colony for Spain while looking for the fabled Seven Cities of Gold--Cibola. Leading an army of 1,200 men, most of which were Aztecs, Coronado made his way into the country north of Mexico. Six months into the march, they rode into a cluster of Zuni pueblos, Cibola, near present-day Gallup. He attacked the Zuni at Hawikuh, taking over the principal pueblo and its food stores for his famished soldiers.

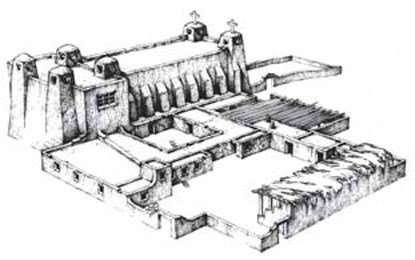

NPS Image/Lawrence Ormsby Colonizers and MissionariesNearly 60 years passed before Spaniards came to New Mexico to stay. New Spain's frontier had slowly advanced with the discovery of silver in northern Mexico. In 1581, explorers began prospecting for silver in the land of the Pueblos. Their failures foreshadowed a truth that determined much of Spanish New Mexico's history: that province held neither golden cities nor ready riches. But the fact that settlers could farm and herd there focused the joint strategies of Cross and Crown: Pueblo Indians could be converted and their lands colonized. Don Juan de Oñate was first to pursue this mixed objective, in 1598. Taking settlers, livestock, and 10 Franciscans he marched north to claim for Spain the land across the Rio Grande. Right away he assigned a friar to the pueblo the Spanish would call Pecos, the richest and most powerful in New Mexico. The new religion got off to a shaky start. After episodes of idol-smashing provoked Indian resentment, the Franciscans sent veteran missionary Fray Andrés Juárez to Pecos in 1621 as healer and builder. Under his direction the Pecos built an adobe church south of the pueblo, the most imposing of New Mexico's mission churches-with towers, buttresses, and great pine-log beams hauled from the mountains. The ministry of Fray Juárez from 1621 to 1634 coincided with the most energetic mission period in New Mexico, now a royal colony. It was a Franciscan-led time of mission building and expansion. Its success bred conflict. Church and civil officials vied for the Pueblo Indians' labor, tribute, and loyalty.

NPS Photo The Pueblo RevoltThe Indians suffered these struggles through religious and economic repression. Decades of Spanish demands and Indian resentments culminated in the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. The Pueblos, including Pecos Pueblo, united to drive the Spaniards back to Mexico. At Pecos, those loyal to the Spanish and the padres warned the local priest but most followed a tribal elder in revolt. They killed the priest and destroyed the church. Twelve years later, led by Diego de Vargas, the Spaniards came back to their lost province, peacefully in some places but with the sword in others. De Vargas expected fighting at Pecos, but opinion had shifted.

Though there was still some division within the pueblo, some of the people accepted him and supplied 140 warriors to help retake Santa Fe. A smaller church built on the remains of the church destroyed in the Pueblo Revolt was built by 1717. The Franciscans moderated their zeal. The practice of encomiendas (paying tribute) was abolished, but different forms of indentured servitude continued. As allies and traders, the Pecos became partners in a relaxed Spanish-Pueblo community.

By the 1780s, disease, Comanche raids, and migration reduced the population of Pecos to fewer than 300. Much of the good farmland was being used by encroaching cattle herds and new Hispanic Ranche, making agriculture increasingly difficult. Longstanding internal divisions-those loyal to the Church and things Spanish versus those who clung to the old ways-may have contributed to this once powerful city-state's decline. The function of Pecos as a trade center faded as the Spanish, now protected from the Comanches by treaties, established new towns east of the pueblo.

Pecos and the mission seemed almost ghostly when Santa Fe Trail trade began flowing past in 1821. The last survivors left the decaying pueblo and empty mission church in 1838 to join Towa-speaking relatives 80 miles west at Jémez pueblo, where their descendants still live today. |

Last updated: September 20, 2025