Last updated: April 21, 2025

Person

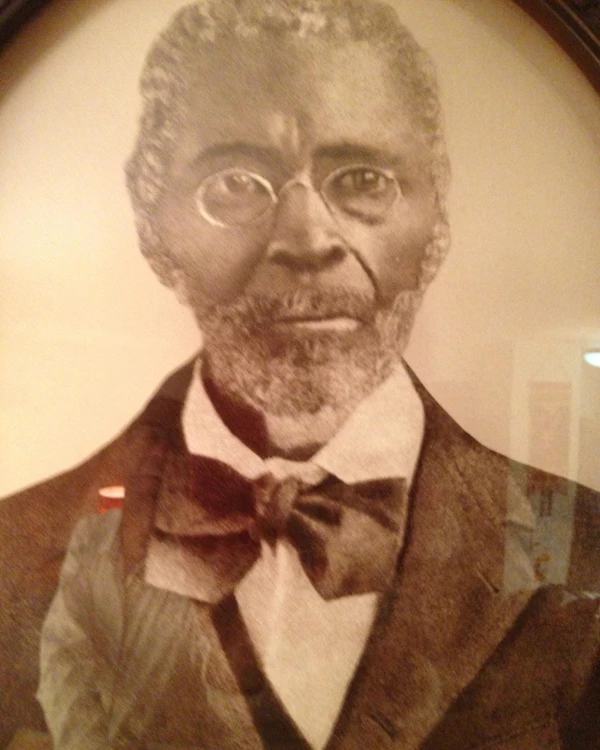

Charles Diuguid

Charles Diuguid was a blacksmith whose shop was almost directly across the road from the McLean House in the village of Appomattox Court House. He seems to have been relatively prosperous and even had six enslaved people listed as his property in 1860. At first glance Mr. Diuguid may appear to be a typical local craftsman, but he was uncommon in several ways. Charles Diuguid was African American, one of about one hundred “Free Blacks” in Appomattox County at the time of the Civil War. Also, the enslaved people in his household were his wife and five children.

Why did Charles Diuguid choose not manumit his family? Most likely because of the unsettling truth that it was easier to protect them as enslaved people than if they were free. Simply put, there were more due process protections for property under Virginia law than there were for free African Americans. A free African American could be arrested by almost any white male and charged with a plethora of crimes that would result in the African American being sold into involuntary servitude. African Americans could not testify against whites, so there was little to no way to mount a defense if an African American, free or enslaved, was charged with a crime. Property, however, was protected much more stringently.

Diuguid, like many free blacks, personally experienced his lack of rights and citizenship under the Confederate system when he was involuntarily impressed twice as an uncompensated laborer for the Confederate Army, first in 1861, to help dig earthwork defenses in Northern Virginia, and again in 1864 to help construct defenses around the besieged city of Richmond. In testimony to the Federal Claims commission Diuguid clearly understood that free blacks did not have personal rights. He reported that when the local sheriff “recruited” him, “I would have to go and if I didn’t go, he would have cuffed me. I had no more rights than the slaves.”

Diuguid was in Appomattox on the morning of April 9th when the Confederate Army surrendered. His land was along the line the Confederates formed west of the village in their last attempt to break through the Union forces that had effectively surrounded them. No one in Charles Diuguid’s family left any record of their thoughts or observation about the surrender. The only record associated with them is the unsuccessful claim Diuguid filed to get compensation for livestock that Union soldiers took at the time of the surrender.

The end of the institution of slavery may have given rise to hope for freedom, equality, and opportunity for men like Charles Diuguid and his family, but the advent of Jim Crow Laws and other forms of institutionalized segregation and discrimination meant that those hopes and dreams were unjustly deferred. Diuguid and his family had to struggle to create those opportunities for equality, first by exploiting loopholes in the Slave Codes to keep their family intact and then, after the war, through migration.iuguid and his family finally left Appomattox for Ohio in 1879.