Last updated: November 2, 2024

Person

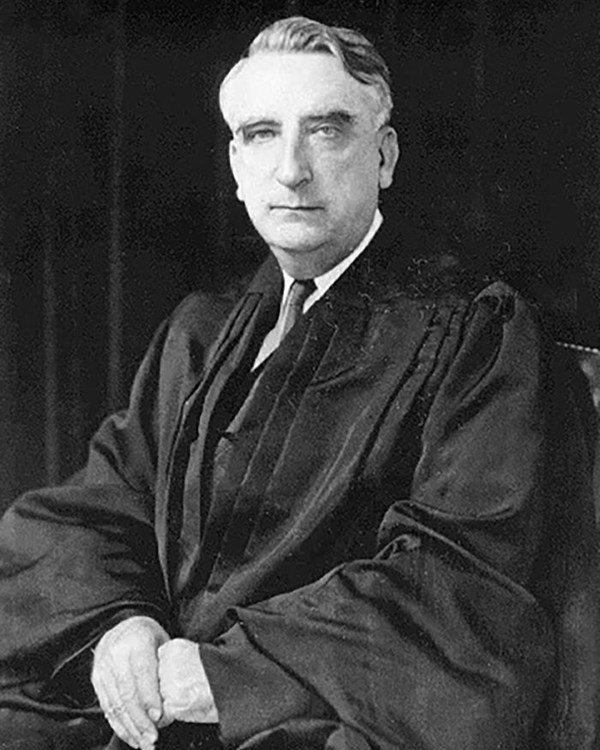

Chief Justice Fred M. Vinson

Chief Justice Fred M. Vinson was a lawyer and Secretary of the Treasury who was nominated by President Harry S. Truman on June 6th, 1946, to serve as 13th Chief Justice of the United States. Prior to this, he had a long and distinguished career in public service as a congressman and judge on the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit. As chief justice, he was one of nine justices who would hear oral arguments on December 9, 1952, concerning the five school segregation cases that made up the Brown v. Topeka Board of Education lawsuit.

As Chief Justice, Vinson wrote the Supreme Court’s opinion in famous Sweatt and McLaurin cases. Both Sweatt and McLaurin were Black prospective law students who had special conditions attached to their admittance to law school. Sweatt, who was originally denied admission to University of Texas law school altogether because of his race, could attend his own makeshift school in the basement of a building while the state built a separate law school for Blacks. McLaurin was admitted to University of Oklahoma law school, but had special accommodations: he would listen to lectures from an anteroom to the hall where white students sat.

With experience as a former lawyer, Vinson believed that no “special” Black-only law school could ever give its students what they could get in the law department of a well-known university, such as tradition, prestige, and networking opportunities. Vinson’s opinion went further, delivering a new logic to the role of the Constitution. He said that because both the lawyer and his clients had rights that needed protection under the Constitution, how could a school deny admittance to a qualified Black applicant who was seeking training to better serve his future clients? Adhering to this logic meant that segregation would be unconstitutional in all colleges and universities, not just in graduate and professional schools.

When the Supreme Court justices gathered in December of 1952 to offer opinions on the five court cases comprising Brown v. Board of Education and the future of segregated schools, the majority of them, Vinson not included, were in favor of ending segregation in public schools. Justice Vinson indicated that he was ready for segregation to end in Washington DC schools, but not in the rest of thecountry. However, Vinson would never see the court’s eventual decision to end “separate, but equal” in education come to life; on September 8, 1953, a month before arguments were scheduled to be heard, Vinson died of a heart attack. Vinson was succeeded by former governor of California, Earl Warren, through an appointment by President Dwight D. Eisenhower.