Last updated: March 6, 2023

Person

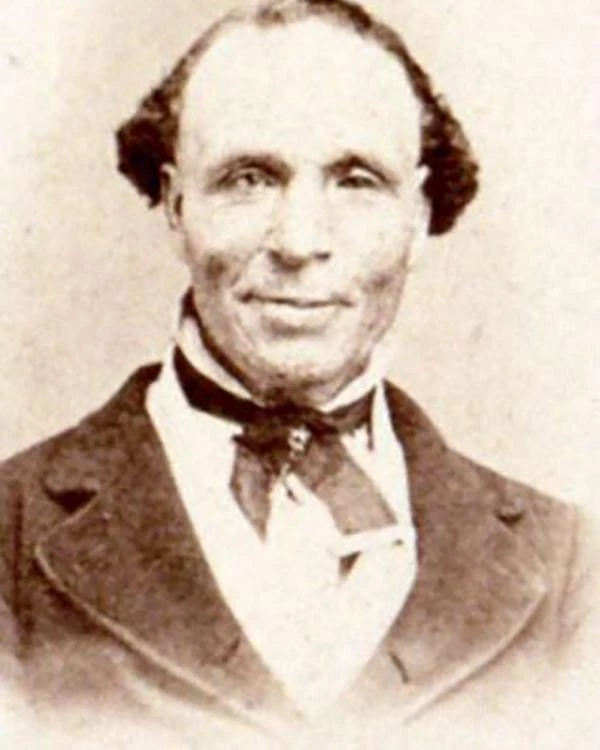

Elijah Abel

Photo/Public Domain

Elijah Abel (also spelled Able or Ables) was born in Maryland in 1810, possibly into slavery. An early convert to Mormonism (officially, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, or LDS Church) and one of the faith’s first Black members, Abel gathered with other Latter-day Saints in Kirtland, Ohio, soon after his 1832 baptism. Four years later, in 1836, Ambrose Palmer—a presiding Elder in Ohio—ordained Abel. Later that year, in December, Abel was ordained a Seventy (a member of an important council of Church leaders) by Zebedee Coltrin; this distinction gave him limited authority to organize and proselytize on behalf of the Latter-day Saints, with the primary duty of administering and spreading the LDS faith. Also in 1836, at the direction of LDS Church founder Joseph Smith, Jr., Abel received his ritual washings and anointings in the Kirtland Temple. He also received a blessing from Joseph Smith, Sr., the patriarch of the church. Abel’s patriarchal blessing was different from those received by his fellow white Saints. Smith pronounced him an “orphan,” promising that “thou shalt be made equal to thy brethren, and thy soul be white in eternity and thy robes glittering.” Abel’s blessing showed that, while Black people could claim some space in early Mormonism, they were also subject to a racial “othering” that differentiated them other church members.”

In the earliest years of his missionary service, Abel labored in New York and Canada, where his activities generated enough controversy among non-Mormons and his fellow missionaries that church leaders took notice. Non-Mormon residents of St. Lawrence County accused Abel of murdering a woman and five children, but he successfully fought the charge. After that, his fellow missionaries in Canada complained about the content of his teachings and claimed that Abel had threatened to assault a fellow missionary. (He admitted to the latter, but with the rejoinder that “knocking around with Brothers” was commonplace.) Church leaders chose not to take any disciplinary action against him.

In 1839 Abel left Canada for Nauvoo, Illinois, where Joseph Smith, Jr. and about ten thousand of his followers had relocated after their expulsion from the state of Missouri. Abel spent three years there living on property he purchased from Smith. During that time he employed his carpentry skills, even serving as an undertaker in what had become one of the state’s most populous cities. In 1842, for reasons that remain unclear, Abel moved to Cincinnati, Ohio, where he helped serve the local LDS community as a church leader. While in Cincinnati, Abel met and married Mary Ann Adams, a Black woman who had been born in Tennessee in 1829—making her approximately twenty years younger than her new husband.

Abel had grown close to the Smith family while in Nauvoo, and his activities in New York and Canada added to his notoriety. His visibility as a Black ordained elder, however, created some consternation among other church leaders. In 1843, during a regional conference in Cincinnati, apostles John E. Page, Orson Pratt, and Heber Kimball presided over a discussion of Abel’s standing in the church. Page argued that, while he respected Abel, “wisdom forbid that we should introduce [him] before the public.” In other words, given the nation’s deep divisions over issues of race and slavery, Page thought it unwise for the Latter-day Saints to appear racially progressive. Pratt and Kimball echoed Page’s concerns and the trio drafted a resolution to restrict Abel’s duties, confining him to local work and instructing him to work only with Cincinnati’s Black population. The conference marked the first documented placement of racially-based restrictions upon a priesthood officeholder.

Following the death of Joseph Smith at Carthage, Illinois, in 1844, Latter-day Saints moved to the Great Basin—where Abel found further changes for him as a Black member of the church. The exact reasons for these changes are not entirely known. One factor, however, appears to be the tensions that arose from the confluence of U.S. territorial expansion and the nation’s mounting sectional crisis that led to the Compromise of 1850 and legalization of slavery in the newly-formed Territory of Utah. In 1852 Brigham Young, Joseph Smith’s successor and Utah Territory’s first governor, addressed Utah’s newfound status as a slave territory by telling the territorial legislature that men of Black descent were not eligible for the priesthood. Consequently, neither Black men nor women would be allowed to participate in the temple endowment or sealing ordinances.

The following year Elijah and Mary Ann migrated to Salt Lake City along with their children Moroni, Enoch, and Anna. That same year, Abel petitioned Young to receive the temple endowment and be sealed to his wife and children. While Young officially kept Abel’s priesthood status intact, he denied the petition—marking perhaps the first documented instance of a person of color being denied this particular privilege. More broadly, this refusal was one of the first times that a person of color was denied participation in practices central to the Mormon faith.

After Young’s death in 1877, Abel again petitioned to be allowed to participate in the temple endowment and sealing ordinances. Once again, however, the church refused him. Despite being denied full access to the rights and privileges of the priesthood, Abel remained devout and soldiered on with his missionary activities. He served three more missions, making his last trip to the eastern states in 1883, the year before his death. Abel died on 25 December 1884, due to “exposure while laboring in the ministry in Ohio.”

When Young made his declaration in 1852 regarding Blacks and the priesthood, he also declared that at some future date Black church members would “have the privilege of all we have the privilege of and more.” In 1978, almost a century after Elijah’s death, the LDS Church re-opened the priesthood to men of African descent. More than twenty years later, in September 2002, the church sent apostle M. Russell Ballard to dedicate a monument that had been erected in Salt Lake City to honor Elijah and Mary Ann Abel’s “[contributions] to the early growth of the state and to their chosen faith.”

(Special thanks to UNM PhD candidate Angela Reiniche for compiling this information; thanks also to Chad M. Orton and Jessica M. Nelson for their editing help.)