Last updated: August 2, 2023

Person

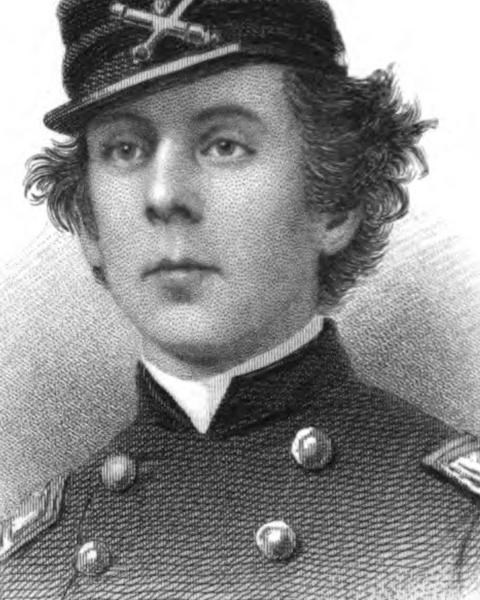

J. Howard Kitching

Hurd & Houghton

New York native J. Howard Kitching enlisted in the US Army at the start of the Civil War. Torn between patriotic duty and family obligations, he fought in several battles and rose to the rank of colonel. Kitching died in January 1865 of wounds he got at the Battle of Cedar Creek.

"Our officers also share the toils and privations of their men. Col. Kitching is an example to us all in this respect. He is untiring in the discharge of his duties and in his devotion to the welfare of his men. He often has no better accommodations than the humblest private in his command. Men will follow such a leader."

— E. R. Keyes

Early Life

Born in New York City in 1838, he was the son of John Benjamin Kitching. John was a British merchant in New York, who invested heavily in in developing technology. These new inventions included the telegraph, undersea telegraph cable, and the Ericsson engine.

Howard seems to have been a sickly youth, whose health improved with vigorous outdoor activities. He had a “passion for riding, boating, painting, and music.” He had a good singing voice and played the cornet but was less interested in more rigorous studies. Howard travelled to Europe with his father in 1855, hoping, without luck, to enroll in a school in Switzerland. Growing up in New York, Howard had visited the US Military Academy at West Point many times and witnessed aspects of cadet training. Yet, “his deep love for his mother, and her decided opposition to a military or naval education” prevented a military career. Howard joined his father in business. He married Miss Harriet Ripley, in Brooklyn, NY in the summer of 1860. That fall, Howard travelled across the South hoping the climate would help his poor health. Instead, he saw the enthusiasm and eagerness displayed across the new Confederacy in the lead-up to the Civil War.

Civil War

Training & Garrison Duty

Although sickly, and devoted to his parents, wife and new son, Howard enlisted in the 1st New York Cavalry, also known as the Lincoln Cavalry. “After drilling with them for several weeks, they were ordered to the seat of war, but family circumstances prevented his leaving with them.” This is the first of many times during the war when “family circumstances” required Howard to return home to his family. Howard then received a captain’s commission in the 2nd New York Light Artillery, organized in Staten Island.

In November 1861, the 2nd New York Light Artillery headed to Virginia to garrison Fort Ward, Fort Ellsworth and Fort Worth. This chain of forts in Alexandria Virginia, protected Washington, DC. According to Captain Kitching, Fort Ellsworth

“is a very fine piece of work on a splendid commanding position, overlooking Washington, Alexandria, and all the surrounding country, for fifteen or twenty miles…. Being second in command in the fort, gives me of course a great deal more to attend to than if I only had my own company to look after.”

During the winter of 1861-1862, Kitching wrote home often. He described army discipline, sickness, camp life and Christmas away from home.

In the Peninsula Campaign

Kitching volunteered to join an artillery battery in combat, as a junior officer. He deployed with Major General George McClellan’s Army of the Potomac in the Peninsula Campaign. According to the "Account of the Sixth New York Artillery from the Highland Democrat of Peekskill, NY,"

“In April 1862, while acting as Captain, in command of a company, in one of the forts around Washington, he volunteered to act as Second Lieutenant of a Regular battery before the enemy, rather than remain idle in the fort. This indicates a character determined to accomplish something for the good of his country, as well as for his own advancement. To this courageous temper Col. Kitching adds a disposition to thoroughly acquire a knowledge of what is the duty of a soldier. He is a strict disciplinarian, and in this is the secret of the success of the Sixth Artillery.”

Kitching first saw combat in the Battle of Eltham's Landing, May 7, 1862. At Eltham's Landing, General William Franklin’s division made an amphibious landing on the banks of the York River. Kitching wrote to his wife,

“My boating experience, as well as my knowledge of horses, was, I hope, of some service that night. If you could have seen me standing at the tiller, steering a huge raft, with one hundred and eighty horses on board, jumping and kicking, and trying their best to get overboard, whilst all the soldiers, worn out with hard work, were sleeping on all sides, you would have wondered what kind of craft I had got into.”

Kitching was at first confident and hopeful about the attack on Richmond. But as the Federal army slowed their advance, Kitching’s letters showed his frustration and homesickness. Captain Kitching fought “with great coolness” at the Battle of Gaines Mills, but under the stress of campaign, became seriously ill. He took sick leave and resigned his position with the Army of the Potomac.

With the Artillery Reserve

Kitching returned home to New York and quickly recovered. Despite the suggestion that he remain at home, he received a commission as Lieutenant Colonel in the 135th New York Infantry. In September 1862, the 135th, then stationed at Fort McHenry, in Baltimore, was redesignated as the 6th New York Heavy Artillery. The 6th left to garrison Harper’s Ferry and in April 1863, Kitching assumed command as colonel. Colonel Kitching and the 6th remained in and around Harper’s Ferry throughout the Gettysburg Campaign. Kitching’s troops fought at the Battle of Manassas Gap, in late July. Federal troops tried to push into the Shenandoah Valley and cut off the Confederate retreat. During the fall and winter, the 6th New York Heavy Artillery camped near Brandy Station in Culpeper County, Virginia. By the spring of 1864, Colonel Kitching reached brigade command. His troops guarded the ammunition and supplies of the Artillery Reserve. They first saw combat at the Battle of the Wilderness.

Commanding an Infantry Brigade

The fighting in the Wilderness and at Spotsylvania caused severe casualties. Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant realized he needed all his troops placed in combat positions. As a result, Kitching and his brigade shifted to a direct combat role as part of the Fifth Corps for the rest of the Overland Campaign. He wrote to his mother, “You had better direct your letters to Kitching's Brigade, Fifth Army Corps; as we are no longer a part of the reserve, but a regular infantry command.”

At Spotsylvania, they fought at Laurel Hill and in the Bloody Angle. Near the Bloody Angle, they attempted to man some cannon that stood abandoned near the front lines. Days later, the brigade held an important position guarding the flank of the Federal Army. Here, at Harris Farm, Kitching’s men repelled a Confederate attack. Leading the attack were Confederate Generals Robert Rodes, John Gordon, and Dodson Ramseur. Kitching’s Brigade received praise from Army Commander Major General George Meade.

“Headquarters Army Potomac, Orders.

May 20, 1864.

The Major-General commanding desires to express his satisfaction with the good conduct of Tyler's Division and Kitching's Brigade of Heavy Artillery, in the affair of yesterday evening. The gallant manner in which these commands (the greater portion being for the first time under fire) met and checked the persistent attack of a corps of the enemy led by one of his ablest Generals, justifies the Commanding General in this public commendation of troops, who henceforward will be relied upon as were the tried veterans of the 2d and 5th Corps, at the same time engaged.

By command of Maj. Gen. MEADE.”

Colonel Kitching’s brigade led the Fifth Corps march to the North Anna River. They often occupied advanced and isolated positions. They fought at the crossing of the North Anna River near Jericho Mills on May 23rd. On May 30th, at the Battle of Bethesda Church, Kitching’s men retreated from a Confederate attack. Once again, leading the Confederate troops were General Rodes, Gordon and Ramseur. Kitching wrote to his wife,

“I had no time to form line of battle; This terrible fire right into the head of the column broke the men, many of whom had fallen, killed or wounded, and in less time than I have been telling you, my brigade, excepting one battalion which I managed, to keep together, was sailing across the plain.”

The attacking Confederates, from North Carolina, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Virginia had fought Kitching’s men at Harris Farm and would face Kitching five months later at Cedar Creek.

Kitching’s brigade served in the trenches near Petersburg. He wrote about life in the rifle-pits and about the army’s disappointment at the failure of the Battle of the Crater. Following Confederate Lieutenant General Jubal Early’s raid on Washington, DC in July 1864, Kitching’s troops left the front lines, assigned to defend the capitol. Kitching wrote to his father,

“My officers and men are delighted to get into nice barracks after living as they have. It seems so queer to be able to lie down at night in quiet, without the danger of being blown to pieces by a mortar shell. I appreciate it, I assure you... You cannot imagine how I thank God in my heart for this quiet the absence of suffering and death which has accompanied our campaign in the field.”

Resignation from the Army

In September 1864, Kitching had the opportunity to visit his family and friends in New York. Kitching had a three-year-old son and he and his wife were expecting another baby in November. According to his friend and biographer,

“Late into the night we sat around him, urging him to leave the service. We pressed the fact that he had done his duty nobly, had shrunk from no sacrifice, and that now the claims of wife and child and mother were paramount, and from other family considerations, it was his duty to remain at home. There were those who needed the support of his strong arm, and now that the Lord had spared him so wonderfully, it seemed but right that he should return to other duties and allow his place to be filled by young men who had fewer claims upon them.”

As a result, Kitching applied to leave the Army. His discharge received approval on October 2, 1864.

But the next day his discharge was revoked. Kitching headed to duty with Major General Philip Sheridan in the Shenandoah Valley. Kitching wrote to his father,

"It is a terrible disappointment to me, for I had struggled with myself very hard...to decide whether I ought to be discharged at this time, and having made up my mind that it was my duty [to my family], and the order having been issued, it cut me terribly to have it revoked...What command I shall have, or what I shall do when I get there, I cannot tell yet."

Kitching arrived in Harper’s Ferry. He organized available troops into a "Provisional Division." This division formed around the nucleus of his old command, the 6th New York Heavy Artillery. The Provisional Division joined Sheridan’s Army of the Shenandoah. It arrived south of Middletown, Virginia, along the banks of Cedar Creek.

Battle of Cedar Creek

In the early morning of October 19th, 1864, General Jubal Early's Army of the Valley attacked out of a dense fog. Kitching's Provisional Division deployed on a ridge. He was next to troops under the command of future President Rutherford B. Hayes. Colonel Hayes asked if Kitching could hold the position, “This is a good position,” Kitching said, “and I can hold on here if you can hold on down there.” Hayes replied, “You need not feel afraid of my line...I will guarantee that my line will stand.”

Overwhelming numbers of Confederate troops attacked the ridge held by Hayes and Kitching. 7500 Confederates against 2500 Federals. These troops were same ones that overpowered Kitching’s men back at Bethesda Church. The Confederate lines overlapped and outflanked the Federal position on both ends of the ridge.

Kitching rode among his men, and tried to rally them, but without success. Major Edward Jones, commander of the 6th New York Heavy Artillery, was hit, and Kitching cried out: “Stop men, you will not let Jones be made a prisoner!” Some New Yorkers turned back to help save Jones. Shortly afterwards, Colonel Kitching received a wound in the foot. He refused to leave the field of battle until the loss of blood caused him to almost lose consciousness. The Provisional Division lost 220 men, more than one out of five.

Returning Home

Kitching went back to New York to recover from his wound; he and his wife welcomed a baby girl on November 14th. Soon after, doctors amputated his foot. Following another unsuccessful surgery, he died of fever due to his wound, January 11, 1865. As a result of his wartime service, Kitching received a brevet promotion to Brigadier General of Volunteers, to rank from August 1, 1864. His brigade returned to Petersburg, Virginia. They served through the Fall of Richmond and the Appomattox Campaign. On January 16, the officers of the 6th NY Heavy Artillery resolved,

"That the character of General Kitching as an officer and a gentleman, was such as commanded our highest respect and esteem. His qualities as a soldier and a leader, whether displayed in the quiet of camp or in the storm of battle always secured the earnest confidence of all. We feel that no one can supply his place with us. He died for his country, but his memory will ever live in our hearts as that of a good man. a true soldier and a gallant officer."

References:

More than Conqueror or Memorials of Col. J. Howard Kitching, by Theodore Irving.

" 6th Heavy Artillery Regiment." New York State Military Museum and Veterans Research Center. https://museum.dmna.ny.gov/unit-history/artillery/6th-heavy-artillery-regiment

Official Records of the War of the Rebellion, Volume XXXVI Part III, page 60.

The Battle of Cedar Creek: Showdown in the Shenandoah, by Theodore C. Mahr.

The Battles for Spotsylvania Courthouse and the Road to Yellow Tavern, May 7-12, 1864; To the North Anna River, Grant and Lee, May 13-25, 1864; Cold Harbor, Grant and Lee, May 26-June 3, 1864; by Gordon C Rhea.