Last updated: January 20, 2024

Person

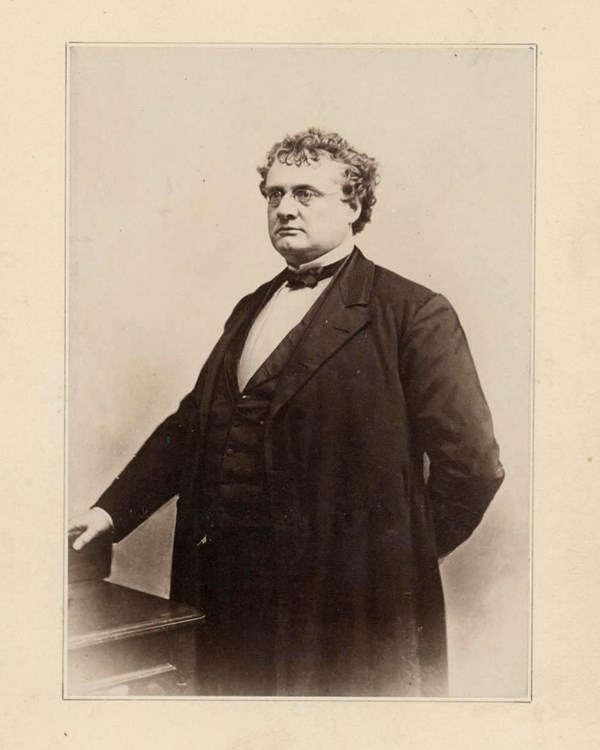

John Albion Andrew

Massachusetts Historical Society

According to his obituary, "At a period when the State required its wisest and best man at the head of the Government, John A. Andrew was selected."1

Known as the "great War Governor"2 of Massachusetts, John Albion Andrew's leadership during the Civil War and commitment to anti-slavery in his legal and political career earned him widespread admiration and respect. Andrew led the efforts to enlist African American men as soldiers and organized the famous 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment. As a friend and champion of "the poor, the wretched, the sick, even the vile,"3 Andrew's earnest and sympathetic character proved to be his strongest asset.

Born and raised in Maine, John A. Andrew attended Bowdoin College. After graduating in 1837, Andrew went to Boston, studied law under Henry H. Fuller, and passed his bar exam in 1840.4 As a man with strong religious views, Andrew attended the Church of the Disciples and befriended church leaders, including Reverend James Freeman Clarke and Reverend Leonard Grimes.5 Guided by a sense of religious and civic duty, Andrew's legal knowledge and beliefs worked hand-in-hand "on behalf of the oppressed and the defenseless."6

Andrew advocated for social causes by joining reform groups including anti-slavery organizations. He served as a member of the 1846 and 1850 Boston Vigilance Committees.7 Bostonians founded the 1850 Vigilance Committee in response to the passage of the new Fugitive Slave Law, the controversial law that empowered enslavers and their agents to capture and return freedom seekers to bondage with the full backing of the federal government.

Almost at once, Andrew began to provide legal defense to freedom seekers and those who aided them, including abolitionist Lewis Hayden. Following the rescue of freedom seeker, Shadrach Minkins, Hayden faced examination for his alleged involvement in the affair. Charges against Hayden stated that he had "harbored and concealed him [Minkins] in his house in Southac street."8 Acting as Hayden's counsel, Andrew successfully argued for his acquittal. Andrew also played an important role in the high-profile legal cases of freedom seekers Seth Botts and Anthony Burns.9

Andrew continued to fight against slavery by working within the legal system, and he remained "always ready to defend any person arrested under the Fugitive Law."10 In 1856, a Maine captain and his ship crew discovered a freedom seeker, William Johnson, on their boat. News of Johnson's capture and arrest reached Vigilance Committee members. After allies secured a writ of habeas corpus, Andrew represented Johnson in court and argued for his discharge as "Johnson was the only person on board the vessel at the time of his arrest, except the mate, who is also a colored man."11 After receiving no opposition to this motion, Johnson received a discharge.12

Financial records of the Boston Vigilance Committee include a reimbursement of $37.49 to Andrew for "expenses in Hyannis case,"13 which took place in the fall of 1859. A ship's crew headed to Boston had discovered a hidden freedom seeker named Columbus Jones. Stopping in Hyannis, Captain Gorham Crowell arranged for Jones to be sent back to Florida. News of Jones' capture and return to slavery spread. After arriving in Boston, Crowell and a mate found themselves facing charges for imprisoning and kidnapping Jones. In this case, Andrew argued on behalf of the prosecution.14

In addition to providing legal assistance, Andrew's role as a member of the Finance Committee helped secure funding needed to help freedom seekers find food, shelter, and other survival necessities through the collection of donations and solicitation of subscriptions. According to The Liberator, in 1859 the Committee of Finance reported having raised $6028 which had aided "more than four hundred fugitives."15

By the late 1850s, Andrew grew more involved in politics.16 Originally a member of the Whig party, Andrew went on to help organize the anti-slavery Free-Soil Party.17 In 1859, he served in the Massachusetts Legislature.18 Despite his limited experience in politics, Andrew ran as the Republican nominee for the seat of Governor and won the 1860 election. Sensing a war on the horizon, Andrew made it a priority to prepare the state for war. As a result, Massachusetts became one of the first states to answer President Lincoln's call for troops to defend Washington, DC at the outbreak of the Civil War.19 He also organized one of the first African American regiments in the North, the 54th Massachusetts whose actions at Fort Wagner helped inspire the enlistment of roughly 180,000 African American men in the Union Army. His leadership proved popular with the people of Massachusetts as he won the following annual reelections for his position.

After the Civil War, Andrew chose not to run for reelection and returned to his legal practice. He continued to advocate for social causes until his death in 1867. Buried in Hingham Cemetery, the Robert Gould Shaw and 54th Memorial located across the street from the State House in Boston stands as a testament to the long-lasting legacy of Andrew's achievements.

Footnotes

- James Freeman Clarke, Memorial and Biographical Sketches (Boston, MA: Houghton, Osgood, 1880), 50.

- Peleg W. Chandler, Memoir of Governor Andrew: With Personal Reminiscences (Boston, MA: Roberts Brothers, 1880), 27.

- "Characteristics of John A. Andrew," Lowell Daily Citizen and News (Lowell, Massachusetts), November 6, 1867.

- Samuel Burnham, "Hon. John Albion Andrew," Hon. John Albion Andrew (Boston, MA: New-England Historic-Genealogical Society, 1869).

- Clarke, 10.

- Clarke, 5.

- Manisha Sinha, The Slave's Cause: A History of Abolition (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2017), 393; Austin Bearse, Reminisces of the Fugitive Slave Law Days (Warren Richardson, 1880), 5, Archive.org.

- "The Slave Rescue Examination," Daily Evening Transcript (Boston, Massachusetts), March 3, 1851.

- "Trial for Resisting the U.S. Marshall in the Burns Slave Case," Boston Daily Evening Transcript, April 4, 1855; James Freeman Clarke, Memorial and Biographical Sketches (Boston, MA: Houghton, Osgood, 1880); Kathryn Grover and Janine V. Da Silva, "Historic Resource Study: Boston African American National Historic Site," Boston African American National Historic Site, (2002), 117.

- Clarke, 13.

- "Fugitive Slave Case in Boston," New England Farmer, July 19, 1856.

- "Another Fugitive Slave Case," Boston Recorder, July 24, 1856.

- Account Book of Francis Jackson, Treasurer The Vigilance Committee of Boston, Dr. Irving H. Bartlett collection, 1830-1880, W. B. Nickerson Cape Cod History Archives, Archive.org, 66.

- "The Hyannis Kidnapping Case," The Liberator (Boston, Massachusetts), June 24, 1859, Newspapers.com.

- "Aid to Fugitive Slaves," The Liberator, February 18, 1859, Newspapers.com.

- By 1858 Andrew had moved to what is today 110 Charles Street. National Park Service maps place him at this location. Grover and Da Silva, "Historic Resource Study," 116.

- Henry Greenleaf Pearson, The Life of John A. Andrew, Governor of Massachusetts 1861-1865, vol. 1 (Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin, 1904), 47.

- Chandler, 25.

- Clarke, 24; Chandler, 31.