Last updated: April 10, 2024

Person

Robert Sutton

“…Corporal Robert Sutton was… in all respects the ablest… the wisest man in our ranks… His comprehension of the whole problem of slavery was more thorough and far-reaching than that of any abolitionist… it was his methods of thought which always impressed me chiefly: superficial brilliancy he left to others, and grasped at the solid truth.”1

-Thomas W. Higginson, Colonel, 1st South Carolina Infantry (African Descent)

Robert Sutton was born into slavery on the Alberti Plantation along Florida’s northeastern boundary with Georgia. According to Sutton, many years of his life in bondage consisted of sailing the Saint Mary’s River for the purpose of “lumbering and piloting” for his enslavers, who established themselves in the small village of Woodstock Mills - a steam powered sawmill which was run by 52 enslaved people, including Robert Sutton and his family. Sutton’s escape to freedom in the latter half of 1862 rested solely in his resilience, intelligence, and knowledge of the terrain before him. In a crafted “dugout” canoe, the tall Floridian made his way to Federal lines, and ultimately to the confines of Camp Saxton where he enlisted in the 1st South Carolina Infantry - an all Black regiment which was raised along the Beaufort River by Colonel Thomas W. Higginson. It was here that Sutton, as well as approximately 1,000 other recruits, received the training that would allow them to become an effective fighting force in a war for the freedom of approximately four million people.

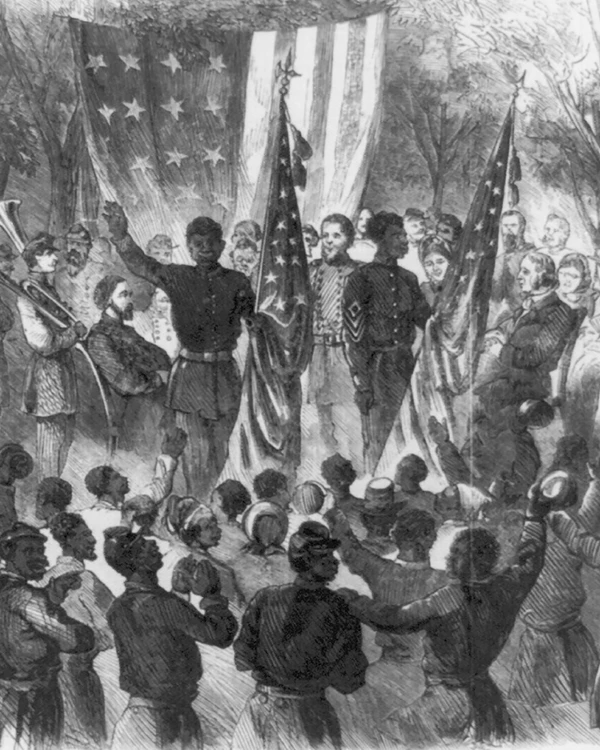

On January 1, 1863, or Emancipation Day, the 1st South Carolina, along with approximately 3,000 other formerly enslaved people from the Sea Islands and Beaufort County region, assembled at Camp Saxton for a reading of President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation. As Colonel Higginson presented the color-guard with the regimental colors, Sutton made a few points to the attentive crowd. According to Harriet Ware, a Bostonian missionary who was present, Sutton “…told them there was not one in that crowd but had sister, brother, or some relation among the rebels still; that all was not done because they were so happily off, that they should not be content till all their people were as well off…”2 Sutton spoke from a place of familiarity, as he had a wife and child confined to the shackles of slavery. Sutton’s pre-enlistment experiences are what drove him to encourage an expedition to his former enslaver’s plantation - a site which could also, in turn, supply the Federal force with an abundance of lumber. Little more than three weeks after Emancipation Day, Sutton, as well as the rest of the 1st South Carolina, had an opportunity to put their training to the test. As Higginson later described, “The whole history of the Department of the South had been defined as ‘a military picnic,’ and now we were to take our share of the entertainment.”3

On January 23, 1863, the regiment set sail down the Beaufort River toward Saint Mary’s River - approximately 120 miles South. A week later, the regiment had orders to retrieve supplies from a brickyard, ultimately to strengthen the defenses of nearby Fort Clinch. The Colonel mentioned that the objective was “near Woodstock, the former home of Corporal Sutton; he was ready and eager to pilot us up the river…”4 That evening, the regiment moved toward Sutton’s former site of enslavement and arrived on the morning of January 30. Colonel Higginson dispatched two companies of his regiment to the small village to secure the area while he prepared the remainder of the regiment to land. Higginson later recalled his observations when he reached the shoreline:

“The chief house, a pretty one with picturesque outbuildings, was that of Mrs. Alberti, who owned the mills and lumber-wharves adjoining… There was lumber enough to freight half a dozen steamers… I called on Mrs. Alberti, who received me in quite a stately way at her own door with ‘To what am I indebted for the honor of this visit, Sir?’ … I wished to present my credentials; so, calling up my companion, I said that I believed she had been previously acquainted with Corporal Robert Sutton? I never saw a finer bit of unutterable indignation than came over the face of my hostess, as she slowly recognized him. She drew herself up, and dropped out the monosyllables of her answer as if they were so many drops of nitric acid. ‘Ah,’ quoth my lady, ‘we called him Bob!’

It was a group for a painter. The whole drama of the war seemed to reverse itself in an instant, and my tall, well-dressed, imposing, philosophic Corporal dropped down the immeasurable depth into a mere plantation ‘Bob’ again… he simply turned from the lady, touched his hat to me, and asked if I would wish to see the slave-jail, as he had the keys in his possession…

I must say that, when the door of that villainous edifice was thrown open before me, I felt glad that my main interview with its lady proprietor had passed before I saw it. It was a small building, like a Northern corn-barn, and seemed to have as prominent and as legitimate a place among the outbuildings of the establishment. In the middle of the door was a large staple with a rusty chain, like an ox-chain, for fastening a victim down…We found also three pairs of stocks of various construction, two of which had smaller as well as larger holes, evidently for the feet of women or children… I remember the unutterable loathing with which I leaned against the door of that prison-house; I had thought myself seasoned to any conceivable horrors of slavery, but it seemed as if the visible presence of that den of sin would choke me. Of course it would have been burned to the ground by us, but that this would have involved the sacrifice of every other building and all the piles of lumber, and for the moment it seemed as if the sacrifice would be righteous. But I forbore, and only took as trophies the instruments of torture and the keys of the jail.”5

The regimental surgeon, Dr. Seth Rogers, mentioned later that Mrs. Alberti attempted to explain away the treatment of the enslaved people on her property, or in his words, she “…spent much time trying to convince me that she and her husband had been wonderfully devoted to the interests of their slaves, especially to the fruitless work of trying to educate them. The truth of these assertions was disproved by certain facts, such as a strong slave jail, containing implements of torture which we now have in our possession, (the lock I have), the fact that the slaves have ‘mostly gone to the Yankees,’ and yet other fact that Robert Sutton, a former slave there, said the statement was false. The statement of a Black man was lawful in Dixie yesterday.”6 The 1st South Carolina returned to the shores of Port Royal on February 2, at which point Colonel Higginson and Dr. Rogers visited the commanding General’s quarters “and laid before him the keys and shackles of the slave-prison, with my report of the good conduct of the men…” This action resonated with the officers of the regiment, as their expedition proved to be a success in paving the way for future factions of African American troops.

Higginson later reflected on this first campaign in his memoirs with a sense of fondness and optimism: “For a year after our raid the Upper St. Mary's remained unvisited, till in 1864 the large force with which we held Florida secured peace upon its banks; then Mrs. Alberti took the oath of allegiance, the Government bought her remaining lumber… By a strange turn of fortune, Corporal Sutton (now Sergeant) was at this time in jail at Hilton Head, under sentence of court-martial for an alleged act of mutiny, an affair in which the general voice of our officers sustained him and condemned his accusers, so that he soon received a full pardon, and was restored in honor to his place in the regiment, which he has ever since held.”7

The accusations against Sutton on the grounds of mutiny were ultimately rescinded. His reputation and war record had reflected an honorable profile which was mirrored in the words of Dr. Seth Rogers, written at the conclusion of the 1st South Carolina Infantry’s first active campaign in 1863: “I have rarely reverenced a man more than I do him… He ought to be a leader, a general, instead of a corporal. I fancy he is like Toussaint l’ Ouverture and it would not surprise me if some great occasion should make him a deliverer of his people from bondage.”8

1 Higginson, Thomas W. Army Life in a Black Regiment. Michigan State University Press, 1960, p. 48.

2 Pearson, Elizabeth Ware, editor. Letters from Port Royal: Written at the Time of the Civil War. 1906.

3 Higginson, 50.

4 Higginson, 63.

5 Higginson, 67.

6 Rogers, Seth. War-Time Letters From Seth Rogers, M.D. Surgeon of the First South Carolina Afterwards the Thirty-Third U.S.C.T. 1862-1863. University of North Florida, www.unf.edu/floridahistoryonline/Projects/Rogers/letters.html.

7 Higginson, 67.

8 Rogers