Last updated: October 21, 2024

Person

Senator Paul H. Douglas

Public Domain

"When I was young, I hoped to save the world. In my middle years, I would have been content to save my country. Now I just want to save the dunes."

In gratitude for his courage, his vision, and his leadership in the effort to preserve this unique landscape, Indiana Dunes National Park is dedicated to the memory of Senator Paul Howard Douglas.

Through careers in teaching and government that spanned half a century, he spoke for the poor and the old, workers and the unemployed, and for citizens denied the full rights of citizenship.

Paul Douglas believed in open space as a source of spiritual renewal, especially for those who spent their working lives, as he did, in cities. He felt that all citizens, rich or poor, should have access to that same source of strength and worked for the last 20 years of his life saving the Dunes so that here it might be so.

Saving the Indiana Dunes

Excerpts from A Signature of Time and Eternity: The Administrative History of Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore

"Indiana's Third Senator" Takes the Dunes Battle to Congress

Approaching Paul H. Douglas to herald the dunes preservation movement in Congress proved to be an excellent move. Although from Illinois, Douglas was no stranger to the Indiana Dunes. Following his 1931 marriage to Emily Taft, daughter of sculptor Lorado Taft, the couple built a summer cottage in the dunes. Summertime and weekends in the dunes with his family left an indelible mark on Douglas' soul. He regarded those times as "one of the happiest periods of our lives":

Like Anateus, I retouched the earth and became stronger thereby. We had rare privacy, with mornings of quiet study and work, afternoons of swimming and walks along the magnificent beach and in the fascinating back country.... What remained was idyllic and an ever-present source of physical and spiritual renewal. I seemed to live again in the simplicities of my boyhood.

Dorothy Buell first approached Douglas to sponsor a bill to authorize an "Indiana Dunes National Park" in the spring of 1957. Douglas, familiar with the negative stance of the Indiana Congressional Delegation, targeted Senator Homer Capehart. Douglas suggested that Capehart could become a hero by leading the dunes effort and thereby have the Federal park bear his name. Intrigued, Capehart told Douglas he first had to consult with the "boys in Indianapolis." The inevitable answer came: the boys "have other plans." Douglas decided he would introduce the legislation himself. Fittingly, he unveiled the bill to establish "Indiana Dunes National Monument" in Dorothy Buell's home on Easter Sunday 1958. He cited the popularity of the Save the Dunes Council as an indication of widespread public support enabling him to go against the wishes of Indiana's political and business community.

Few could have predicted the magnitude of the vehemence unleashed on Senator Douglas. Media, industry, and political organizations combined accusing Douglas with interfering in Indiana's affairs, serving as a Chicago carpetbagger plotting against Indiana's economic development, and working to establish a park to placate the minorities of Chicago. Douglas' opponents derisively referred to him as the "Third Senator from Indiana." Indignant Hoosiers pointed to an underground coalition of Illinois politicians and industrialists who were hiding behind Senator Douglas' "Save the Dunes" movement in order to stop the Port of Indiana. Douglas' nefarious coalition was also believed to be joined by dunes area industry which hoped to keep competitors out. Nevertheless, Paul Douglas introduced his bill, S. 3898, on May 26, 1958.

Later that June, Senator Douglas received a letter of support from renowned American writer, Carl Sandburg:

Dear Senator Douglas:

You should know that I am one of the many who appreciate your toils and efforts in behalf of an Indiana Dunes National Monument. I have known those dunes for more than forty years and I give my blessing and speak earnest prayers for all who are striving for this project. Those dunes are to the midwest what the Grand Canyon is to Arizona and the Yosemite to California. They constitute a signature of time and eternity: once lost the loss would be irrevocable. Good going to you!

Faithfully yours,

Carl Sandburg

In response to an inquiry from Senator Paul Douglas, the Park Service dispatched a team in September 1958 to evaluate an area of undeveloped duneland west and south of Ogden Dunes. The team identified an additional 850 acres which Douglas incorporated into a new 1959 bill, S. 1001. Park Service comments to the Department on S. 1001 were favorable, but there were a few amendments suggested. Park Service officials believed the designation of "National Seashore" was more appropriate than "National Monument." The Service also questioned the excluded areas around Dune Acres, Ogden Dunes, and Johnson Beach, preferring to consider all available land in order to have an area of sufficient size to accommodate heavy use. While the towns themselves should be excluded, the Service wanted unspoiled Johnson Beach to fall within the acquisition area.

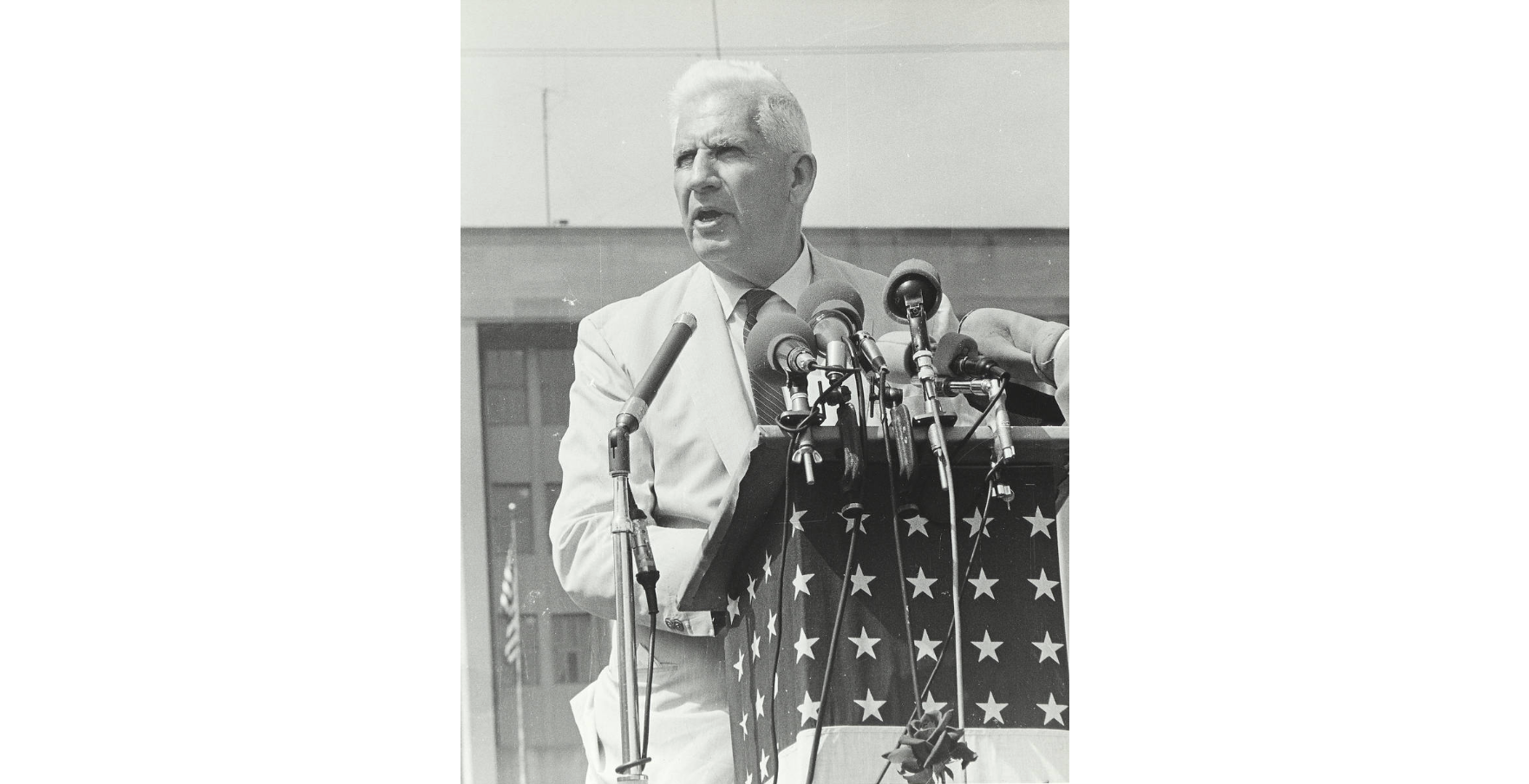

Image caption: Senator Paul Douglas standing in front of a podium

Source: University of Illinois at Chicago. Library. Special Collections Department

On June 13, 1959, Douglas delivered a powerful statement before the U.S. Senate committee considering the legislation:

I am appearing before you in support of S. 1001 to preserve 5000 acres of the Indiana Dunes and prevent them from being destroyed by the erection of one or more steel mills. I cannot exaggerate the importance of this measure. In the great industrial complex which stretches from Gary, Indiana to Milwaukee, Wisconsin, there already live over six million people. And in 20 years, it is estimated that this number will rise to at least 10 million. This great industrial complex which overlaps into three states, and which has Chicago as its core, is one of two or three great productive centers of the world, with an almost unrivalled variety of industries concentrated primarily in the field of heavy goods. But excellently equipped as this area is from the industrial and commercial standpoints, it is short on recreational facilities. Whereas London, Berlin, and Paris have each approximately 200,000 acres of parks and public wooded areas, this region probably does not have more than 65,000.

The great natural wonderland of this region was the Indiana Dunes which 40 years ago stretched for over 20 miles from Gary to Michigan City. Here were mile after mile of unrivalled beaches and high dunes, some wooded and some shifting. A marvellous inland area of woods is interspersed with a lake or two. Here virtually ever variety of tree and flower could and still can be found. It is a paradise for botanists and naturalists as well as the natural recreation area for pent-up people of this area.

In the last 40 years, however, tremendous inroads have been made in this natural paradise. Industry has come into the area. Four real estate subdivisions have greatly restricted the area open to the public. All that is left is a small state park created in the 1920’s largely through the voluntary contributions of Chicago citizens and which is greatly overcrowded, being visited by nearly half a million people in 1958, and about 5000 acres of land is owned by National Steel, headed by Mr. George M. Humphrey with whom we are all acquainted, and Bethlehem Steel. Both of these companies have announced their intention of building steel mills on this site while the State of Indiana has appropriated two million as a nest egg for the development of an industrial port at Burns Ditch for which a federal appropriation of from $35 million to $45 million will later be requested.

The issue is, therefore, squarely joined as to whether we should allow industry to gobble up all these places of natural beauty. In the movie we will show, the unique beauty of the Dunes will be displayed far more eloquently than my words can describe. I can only emphasize that if these mills are built there, with the industrial city which will grow up around them, not only will the Dunes be destroyed but the little state park will itself be made virtually unusable because of the pollution of air and water.

The population is growing rapidly. We are becoming more and more industrialized. Our population is moving citywards. Our cities are spreading over the countryside. We are running out of space and if we do not act quickly, all the places of beauty will be taken over and destroyed. We will have steel mills, cement factories, slag piles and more asphalt jungles and these, I suppose, will be hailed as signs of progress. But we will also have more psychiatric hospitals. When will we realize that all men should have the chance to enjoy the simple things of life which industry seems bent on destroying, namely, the water, the sky, growing and living things and beauty? Must man be compelled to live surrounded by people without having any chance at solitude? Mr. George M. Humphrey can find his solitude by going to his plantation in Georgia where he can invite guests if he so wishes. But the people herded together in our great industrial centers have no such chance and Mr. Humphrey and his associates should not be allowed to destroy the places of recreation for the people.

This brings me to another point. I have been in charge with trying to prevent the coming of the steel mills to Indiana and to obtain them instead for Illinois. Nothing could be farther from the truth. I think it would be fine for Indiana to have these mills, but they do not have to destroy the Dunes and waste $40 million of public money building another port to enable them to do so. There is already a 30-foot deep water harbor at Indiana Harbor where new steel mills could be located; there is a private U.S. Steel harbor at Gary which might be converted into a public harbor; there is an 18-foot harbor at Michigan City which could be deepened for the ore boats and the mills could possibly be located there. The Indiana branch of the Calumet River could be deepened and the mills built near the head of that river in Indiana. There are plenty of sites for steel mills on or near the Indiana shoreline. But there is only one Dunes. Do not destroy them.

The stirring speech delivered on the Senate floor was a forerunner of the conservation movement which blossomed in the late 1960s. It provided for an Indiana Dunes National Monument composed of 3,800 acres in the Central Dunes. On the same day, Representative John Saylor of Pennsylvania—the home state of Bethlehem Steel—submitted a companion bill in the House, H.R. 12689.

With the opening of the St. Lawrence Seaway in 1959, the dunes controversy intensified. Hoosier politicians and businessmen were eager to exploit the economic prosperity promised by the linking of the Great Lakes to the Atlantic Ocean shipping lanes. The Advisory Board on National Parks, Historic Sites, Buildings and Monuments reaffirmed that the Indiana Dunes should be incorporated into the National Park System. Senate hearings in May 1959, saw Douglas and a large group of supporters pleading in vain for swift action on the dunes park bill. An equal number of opponents, from Indiana's Governor to the President of Midwest Steel Corporation, testified against the proposed park. Even as Douglas spoke, an increasing number of power-shovels were decimating the Central Dunes. The same spring, Midwest Steel dusted off its thirty-year-old construction documents and began building a finishing plant on 750 acres at Burns Ditch. Simultaneously, Northern Indiana Public Service Company (NIPSCO) began clearing a 350-acre parcel to build a coal-fired generating plant west of Dune Acres. Douglas accused the industrialists of denuding as much duneland as possible in an effort to make the preservation argument moot.

Port v. Park, 1960-1962

A key element in the port versus park battle involved a U.S. Army Corps of Engineers report commissioned in 1960 to study Indiana's proposed deep—water port at Burns Ditch. The artificial channel, built by a contractor named Burns who was commissioned in 1926, drained the marshlands of the upper valley of the Little Calumet River for development as well as reduced the threat of flooding. For three decades, although not supporting the appropriation of public funds, a series of Corps studies evaluated the Burns Ditch site.

To no one's surprise, the October 1960 Corps report concluded that the mouth of Burns Ditch was the ideal location for the Indiana port and recommended that Congress appropriate the funds. The report called for dredging the lake approach channel to a depth of thirty feet and the outer harbor to twenty—seven feet. With breakwaters and shoreline facilities, the total cost came to $34,500,000. The Corps set the benefit—cost ratio at 5.66 to 1.

When the report arrived for approval at the Board of Engineers for Rivers and Harbors in Washington, D.C., Senator Douglas was ready. He asked why no other alternate sites were evaluated and why the public interest in parkland was not addressed. Until these questions were addressed, Douglas successfully urged the Board to return the report to the Chicago office.

Douglas' move deeply angered Indiana politicians who had boasted that the report's approval would be routine. An aide to Governor—Elect Matthew E. Welsh urged Welsh to "get to the bottom of it." He warned:

It appears to me that the entire project is in jeopardy and the situation is serious. Normally, the Corps of Engineers is considered immune to political pressures but in this instance it would appear from the known facts that Senator Douglas was able to exert considerable influence in securing this latest action by the Corps.

An important ally of Douglas was Save the Dunes Council member Herbert Read, son of artist and Council publicity director Philo B. Read. Read, a dunes advocate who worked for a Chicago architectural firm, became chairman of the Council's Engineering Committee after educating himself on harbors through reading a borrowed technical manual. The self—taught "harbor expert" was able to decipher the Corps of Engineers' formula for calculating benefit—cost ratios. The Engineering Committee demonstrated the Council's resolve to take the offensive. Ogden Dunes resident George Anderson, a railroad research engineer, assisted Read in identifying various harbor alternatives and technical report errors. Channeling the information to Senator Paul Douglas, the result saw the Corps agree to a series of restudies. Herb's wife, Charlotte Read, was also a Save the Dunes member- and future director of the organization.

Interestingly enough, pre—1949 Corps of Engineers' evaluations recommended against a Federally—funded Indiana harbor. As early as 1930, the Corps reported:

The harbor, if constructed, will be entirely surrounded by the plant of the Midwest Steel Corporation, which would make its use by the general public impracticable. The District Engineer recommends that no work be done by the United States at that harbor until it can be shown conclusively that it is of direct benefit to the general public.

Political agitation from Indiana forced another report in 1935 which garnered the same result. The district engineer found the commerce projections "highly speculative" and that the "existing facilities are adequate to supply demand for some years to come." Yet another restudy in 1937 resulted in a report issued in 1943 with an identical conclusion. The Corps recommended that "selection of the site for such an improvement should be based on a comprehensive review of the whole available frontage rather than the consideration of the site of Burns Ditch alone." The report concluded, however, that an evaluation of Indiana's shoreline was unmerited because there was no proof that a deepwater port was needed.

In 1960, for the third consecutive year, the Secretary's Advisory Board recommended Indiana Dunes as a new unit of the National Park System. Life magazine sympathetically displayed a photographic essay in the context of nature against industry. Revealing the destruction of Midwest Steel and NIPSCO bulldozers, one caption warned, "Over the dunes hangs the smoky specter of steel."

Nineteen sixty—one, the first year of President John F. Kennedy's administration and the Eighty—seventh Congress, was the first year in which more than one Indiana Dunes bill was introduced. In the first sign of compromise, Indiana Senator Vance Hartke introduced S. 2317 which provided for both port and park. Paul Douglas submitted S. 1797 which provided for an "Indiana Dunes National Scientific Landmark" of 5,000 acres which he subsequently amended to 9,000 acres. In the House, H.R. 6544 provided for an Indiana Dunes National Monument. Park Service comments, however, favored adopting the language of S. 1797 because the Secretary could lease the lands to the State of Indiana to preserve and manage. The National Scientific Landmark could be administered in conjunction with the Dunes State Park. The bill was designed to allay Indiana's concerns about Federal appropriation of the land. Protection of the leased land could be assured by careful monitoring of State management and protection.

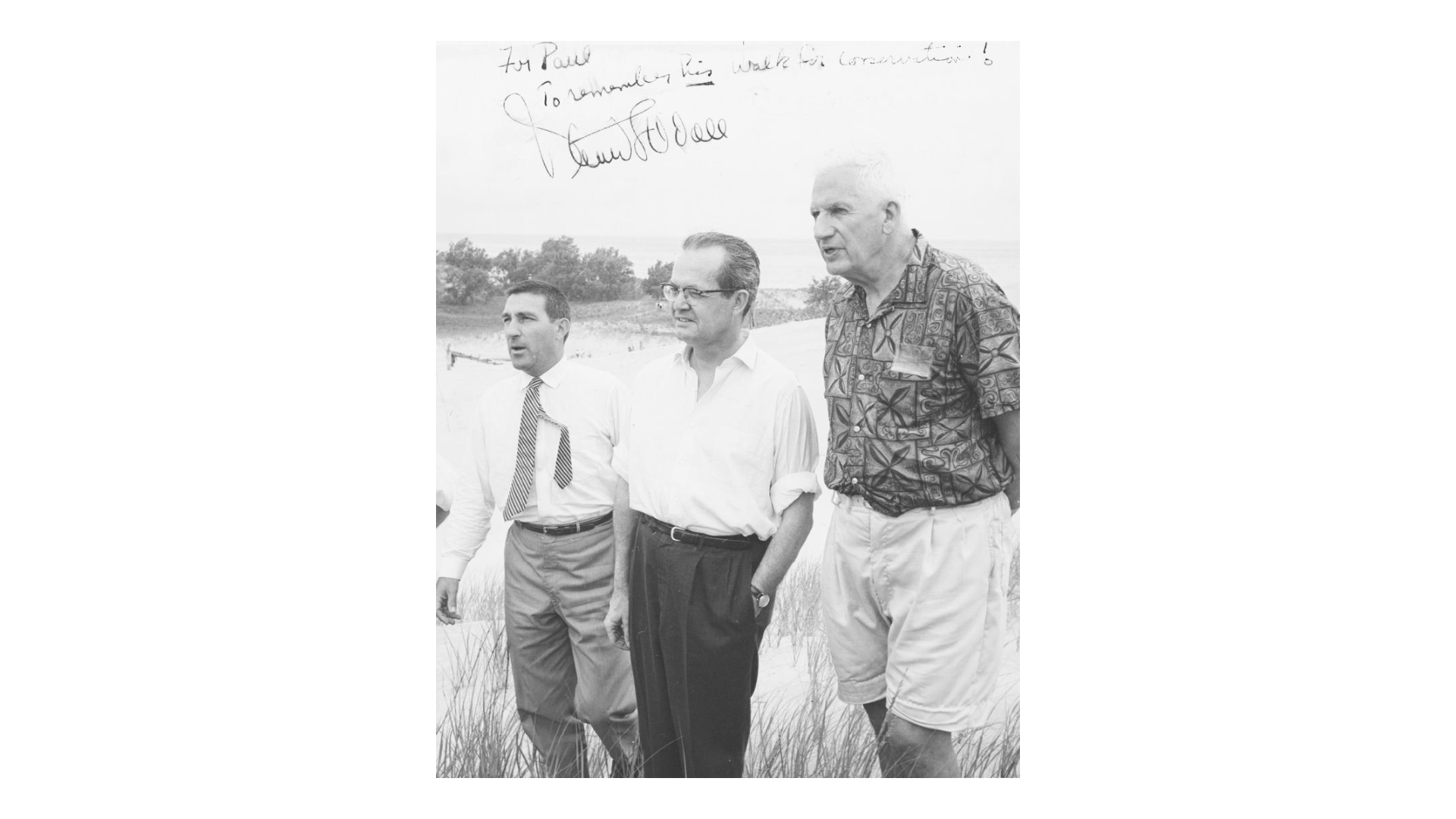

Image caption: Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall (left) and U.S. Senators Alan Bible (center) and Paul Douglas (right). Handwritten notation from Udall reads, "For Paul, To remember this walk for conservation!"

Source: Chicago Historical Society

Douglas coaxed Alan Bible, Chairman of the Parks Subcommittee of the Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, to accompany him and Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall to the dunes to see the proposed park firsthand. On July 23, 1961, Douglas, Bible, and Udall arrived before the Bethlehem Steel property accompanied by an impressive entourage: Director Conrad Wirth; Chicago Mayor Richard Daley; the mayors of Gary, East Chicago, Hammond, and Whiting; and Dorothy Buell. After enjoying a day of hiking and interpretive talks sponsored by the Save the Dunes Council, the participants were converted to the park cause.

In a widely publicized interview, Secretary Udall affirmed his desire to preserve the dunes as a national park and urged prompt Congressional action: "It is my hope that we might preserve as large an area of national significance, not only to serve Chicago or Indiana, but to serve the whole country and future generations as well." To Paul Douglas, Udall asserted,

"We ought to make a last ditch fight to save the dunes as a national park. Our great National Park System has no major unit in the midwestern heartland; your people need something above all. I hope that we can take a walk through the dunes again soon, and that it then will be a great national park."

Image caption: U. S. Senator Paul Douglas, Mayor Richard J. Daley, and Mayor George Chacharis at the Indiana Dunes, 1961

Source: Chicago Historical Society

Before the Senate hearings on S. 1797 began in February 1962, the newly—established Indiana Port Commission (IPC) issued a critical statement on the bill charging Douglas with trying to kill all port planning and sabotage Indiana's economic development. In effect, the IPC declared, the Federal park would encompass and strangle the state's own popular park. The IPC further accused Douglas and his park proponents of spreading malicious propaganda, a "vicious campaign" of heralding a "tourist Mecca" to prevent the public port under the "guise of conservation." Down—playing the tourist potential of the Federal park, IPC cited Secretary Udall's own words: "There will be very little public recreational development. It will, rather, be a preservation of the natural state of the dunes land area. The National Park System is not in the bathing beach business."

Image caption: Senator Douglas and Secretary Udall surrounded by press and citizens holding picket signs both for and against park conservation efforts.

Source: University of Arizona Libraries, Special Collections

On March 11, 1962, the New York Times quoted Senator Douglas:

If they don't let us have the park I will fight them to the death on the harbor appropriation.

While the park appeared for the first time on the administration's priority list, the port also enjoyed White House support. Indiana had a Democrat in the governor's mansion pledged to securing a public port, and the minority leader in the House of Representatives, Charles A. Halleck (Republican—Indiana), had most of the lakeshore area in his district and had launched his political career decades previously based on securing a public harbor for Indiana. Like most Hoosier politicians, Halleck was a self—declared enemy of the proposed park. On March 30, the Indiana Port Commission gleefully declared that Bethlehem Steel contracted for the removal of more than two million cubic yards of sand for use in a landfill at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois. The activity marked the first step in Bethlehem Steel's plans to break into the Chicago steel market by building a new $250 million facility, a move officially unveiled on December 2, 1962. Following the declaration, Douglas issued the following statement:

The announcement of Bethlehem Steel that it has sold two and a half million cubic yards of sand from the Dunes to a contractor who in turn has sold it to Northwestern University to fill in the lakefront at that institution, and that it will start to destroy the Dunes on May 1st, is a brutal and anti-social act. It is an attempt to confront the Congress and the President with an accomplished fact, before they can move to save this rarely beautiful area for the people… and for posterity. It is like attacking and mutilating a beautiful woman so that she may not belong to any one else.

The business manager of Northwestern University is reported to have friends of the Dunes that he did not care where the sand came from and that Northwestern was determined to go ahead with the contract, and furthermore, that he would not discuss the matter. I cannot believe that this attitude represents the real opinion of the President, trustees, faculty, alumni and students of this great university, and I appeal to them to reverse this position. If Bethlehem is deprived of a market for the sand it may be deterred from destroying the Dunes. Northwestern by using the sand becomes partner to the crime. Because a university is the repository of the intellectual heritage of the past, and helps to create the culture of the future, I still hope that Northwestern will not lend itself to this wanton destruction. For the Dunes are a priceless gift of nature, a peerless recreation area created over the millennia of time, and a famous laboratory for naturalists. They should be saved as the everlasting heritage of mankind…

May I also make one final appeal to the officers, directors, and stockholders of Bethlehem to call of their brutal plan. Does that corporation want to be known to the nation and to posterity as the ravager and destroyer of nature? Bethlehem has only a few days in which to redeem itself…

Time is of the essence. The friends of beauty and of the outdoors should rally to the defense of this uniquely beautiful area.

Fearing that the industrial—political coalition might succeed in decimating the Central Dunes, Senator Douglas vowed to oppose appropriations for Burns Harbor until the park became a reality. At this point, Douglas knew the Kennedy White House wanted the port more than the park. He observed that the President's advisors exhibited typical Eastern arrogance in that they considered nothing in the Midwest worthy of preservation.

Douglas' suspicions proved correct when he learned in early October 1962 that President John F. Kennedy had approved the Bureau of the Budget's inclusion of Burns Harbor in the 1962 Public Works Bill. Paul Douglas immediately went to the White House to speak to President Kennedy. He shared with the President his well—worn photographs of the dunes, comparing the area's beauty and uniqueness to that of Kennedy's own beloved Cape Cod National Seashore. Douglas seized the opportunity to raise doubts about the validity of the fluctuating cost—benefit projections contained in the Corps of Engineers report, which had been revised from 5.66 to 1 in 1960 to 1.47 to 1 in 1962. He argued that the issue transcended politics. The dunes had to be preserved at all costs.

The meeting with Kennedy resulted in the President rescinding his approval of the port project. Additionally, he instructed the Bureau of the Budget to re-evaluate the economic potential of the harbor as well as to seek an avenue of compromise to establish both a port and a park. On October 3, 1962, an emergency meeting took place in Senator Douglas' office with Bureau of the Budget (BOB) and Corps of Engineers officials listening to a recitation of errors contained in the Corps' Burns Harbor report. Such in—depth analysis to dispute the Corps' findings was a shockingly unprecedented act. The result saw BOB reject the port proposal. The elimination of the port from the administration's agenda outraged port proponents who universally denounced Douglas' interference. New battle lines were drawn in early 1963 as the highly charged port versus park struggle entered a new stage.

The Kennedy Compromise

While bulldozers were leveling the middle of the Central Dunes in order to build the new Bethlehem Steel plant, Senator Douglas introduced yet another park bill—S. 650—to save the remainder of the dunes. Boundaries were adjusted to include unsold tracts in Dune Acres as well as land west of Ogden Dunes owned by Inland Steel. For the fourth time the Advisory Board on National Parks, Historic Sites, Buildings and Monuments recommended that the area be preserved through the establishment of a national park.

Douglas privately felt the National Park Service was no longer as staunchly committed to the proposed park now that the largest unspoiled area outside the Dunes State Park was gone. While he had the tacit support of the administration, Douglas repeatedly encountered only lukewarm Interior Department approval. He believed this new attitude was dune in large part to tremendous political pressures as well as to the fear of harmful pollutants from the increasing number of area blast furnaces. Douglas later wrote disdainfully of the Service (by referring to it incorrectly) and its Director: "The Eisenhower—appointed head of the Bureau of Parks, Conrad Wirth,* who had endorsed the Dunes proposal, reversed himself in public before the opposition of Capehart and his merry men. He is regarded as a great conservationist."

In a repeat of the October 3, 1962, emergency meeting in Senator Douglas' Washington office, officials of the Department of the Army, Corps of Engineers, and Bureau of the Budget met with Douglas and Save the Dunes Council Members Herbert Read and George Anderson on June 28, 1963. The Council members detailed three alternatives for Burns Ditch Harbor designed to save the shoreline dunes of the Bethlehem Steel tract, also known as "Unit 192." This meeting led to a Save the Dunes Council—led tour of the area for Senator Douglas and George B. Hartzog, Jr., Associate Director of the National Park Service.

In August 1963, a Park Service report identified new areas to replace that lost to the steel mill. The report, compiled by an inter-disciplinary team from the Washington Office and Northeast (formerly called Region V from 1955 to 1962) Regional Office, excluded both the Bethlehem Steel and Burns Ditch Harbor areas from consideration, but did target areas to the immediate south for inclusion in the park. The report identified a national lakeshore composed of four distinct units with a combined shoreline total of eight and three—quarters miles.

In yet another high—level meeting in Senator Douglas' office with the same cast of players on September 5, 1963, the Corps of Engineers responded to the three harbor alternatives proposed by the Save the Dunes Council. Ominously, despite Douglas, Read, and Anderson's best arguments, the Bureau of the Budget (BOB) concurred with the overall Corps position. The proposals were "not acceptable to local interests," i.e., the two steel companies. In a last—ditch effort, the Council appealed to Bethlehem Steel officials themselves. Although the corporation agreed that the alternatives for preserving the lakeshore dunes were feasible, it had already made up its corporate mind.

In September 1963, BOB completed its study as requested by President Kennedy. The so—called "Kennedy Compromise" ensued. BOB recommended the establishment of an 11,700-acre national lakeshore. Under BOB direction, the Corps of Engineers report included alternate port sites, but for the recommended Burns Ditch Harbor site, the Corps listed reservations in accordance with the Save the Dunes Council view. Before Federal money could be expended, environmental and economic considerations had to be satisfied.* The "Kennedy Compromise Bill," drafted by the National Park Service, provided for an Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore in accordance with the August 1963, Park Service report. In a conference call to the Save the Dunes Council, Douglas recommended acceptance of the compromise even though the Central Dunes would be lost. To continue the fight, Douglas believed, would extend the deadlock indefinitely and then no duneland would be left to save. After much agonizing, the Council concurred.

On October 21, Senator Henry M. Jackson, Chairman of the Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, introduced S. 2249 on behalf of Paul H. Douglas, Clinton P. Anderson, Vance Hartke, Birch Bayh, and a score of other cosponsors. The support of both Indiana Senators Bayh and Hartke was a heartening testimonial to the spirit of compromise. In the House, Rep. Morris Udall of Arizona introduced a similar bill, H.R. 8927, which was cosponsored by, among others, Rep. J. Edward Roush of Fort Wayne, Indiana.

Despite the hopeful outlook engendered by the compromise, swift Congressional action was not to be. With the assassination of John F. Kennedy in Dallas the following month, the transition to the administration of President Lyndon B. Johnson, and the frenzied enactment of many of the New Frontier programs kept the Congress from considering the dunes park bills. Hearings were held in the Senate Public Lands Subcommittee from March 5 to 7, 1964. Approximately fifty witnesses testified. It became apparent on the first day of hearings that not all of Indiana's Congressional Delegation was willing to ride on the bandwagon of compromise.

The stalwart leader of the opposition was Representative Charles A. Halleck. Halleck recounted the effort since 1935 to secure a public port to "open Indiana as a gateway of the greatest agricultural and industrial area" in the nation. Halleck objected to surrounding the port and steel mills with parkland because it would destroy the area's economic potential, thereby depriving his constituents of thousands of jobs. He cited the overwhelming local opposition to the Federal Government preserving the dunes when the State of Indiana had already incorporated a prime dunes tract into the State Park System—a unit which Halleck affirmed Indiana would never give away. He criticized the National Park Service for advocating the inclusion of land which did not even feature dunes. As for Park Service plans to establish nature trails near the industrial zones, Halleck scoffed, "I can't conceive of anyone even walking across the street to explore some of those parcels."

A spokesman from the Gary Chamber of Commerce expressed his displeasure over the wide expanse of the park. A resolution from the Porter County Board of Commissioners stated unalterable opposition to any Federal park in northern Porter County. Another resolution from the town board of Beverly Shores also expressed opposition as did the Beverly Shores Citizens Commission which questioned the apparent discrimination in excluding "wealthy and powerful" Ogden Dunes and Dune Acres from the park. Other Beverly Shores representatives asked the committee to either include all of the town within the national lakeshore or compensate the town for the loss of sixty percent of its tax base.

The testimony of Secretary of the Interior Stewart L. Udall was decidedly favorable. Secretary Udall declared that to his knowledge the twenty—six Senators cosponsoring S. 2249 were the largest number of patrons for the establishment of any unit in the history of the National Park System. Udall recognized the national support base for the preservation of the dunes. He expressed disappointment in the preceding negative testimony in light of the best efforts initiated by John F. Kennedy in early 1963 to secure a compromise. Udall praised the committee for approving Point Reyes National Seashore on the Pacific Coast, Cape Cod National Seashore on the Atlantic Coast, and for considering the pending Fire Island National Seashore in New York. The Secretary pointed out that Mid—America was also a prime area for a national park unit in the form of Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore.

The highlight of the hearings was the well—delivered plea of Senator Paul Douglas. Calling the establishment of Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore the "most important conservation issue before the nation," Douglas lauded the efforts of the Save the Dunes Council:

"This is undoubtedly one of the most public spirited, courageous, and self—sacrificing volunteer groups in the nation."

In August 1964, the Senate Interior and Insular Affairs Committee reported S. 2249 favorably and it passed the Senate on September 29, 1964. With the 88th Congress facing its closing months, the conservationists remained hopeful as Representative J. Edward Roush presented a companion bill, H.R. 12096, in July 1964. They were realistic, however, faced by the powerful coalition of park opponents led by the uncompromising Charles A. Halleck and Inland Steel."[Do] not lose sight of the fact that this compromise plan gave up to the bulldozers the most beautiful section of the Indiana Dunes. The loss is tragic. No words and no amount of profit to anyone can possibly justify the inability or failure of our society and Government to preserve the irreplaceable 'Unit 2' section of the park."

Authorization of Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore

By the end of 1964, the Roush bill effectively died, bottled up in the House Interior committee. With the convening of the 89th Congress, Roush reintroduced the bill in early 1965 and it received the designation H.R. 51. Senator Paul Douglas and Representative Charles Halleck continued their port versus park political machinations. For his part, Douglas worked for the Senate to approve the Public Works Omnibus Bill of 1965 which included a stipulation providing that no funds be appropriated for Burns Ditch Harbor until Congress designated the Indiana Dunes a national lakeshore. When the bill reached the House, Halleck not only saw that the measure was deleted, but he inserted a clause forbidding any linkage between port and park. In conference committee, Senator Birch Bayh of Indiana worked for a compromise. In the final bill, Douglas prevailed when Congress approved the Burns Waterway Harbor (Port of Indiana), but appropriations could only come with the authorization of an Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore by the adjournment of the 89th Congress in late 1966.

From his years of experience in Congress, President Lyndon B. Johnson knew the history of the port versus park battle well. He adopted his predecessor's stand on the dunes, the so—called "Kennedy Compromise," without pause. In his February 8, 1965, State of the Union speech, President Johnson declared that the number of parks, seashores, and recreational areas did not satisfy the needs of an expanding population. Johnson proposed that maximum appropriations from the newly implemented Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF) be utilized to make the 1960s a "Parks—for—America" decade. He listed twelve proposed national park areas he intended to target LWCF monies to acquire. Two Great Lakes units were on the list: Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore, Michigan, and Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore.

In early 1966, the Department of the Interior produced an updated feasibility proposal to Congress on Indiana Dunes. Ten thousand copies were printed for the Department, made possible through the use of private funds. The Izaak Walton League ordered 7,000 copies direct from the printer for its own distribution. Needless to say, Indiana, Washington, D.C., and other areas were saturated with the positive report.

When House Interior and Insular Affairs Committee hearings resumed in April 1966, the National Park Service was confident that finally the dunes bill would be reported out of committee. Of notable importance, the State of Indiana's position had mellowed. It sought to capitalize on the proposed park out of its own self—interest. While Indiana welcomed the Federal Government acquiring lands immediately bordering on the Dunes State Park, the State remained diametrically opposed to donating its parkland. Rather, it wished to lease the new Federal areas and thereby forego National Park Service management. The State frowned upon acquisition of noncontiguous areas, such as the Inland Steel property, as an attempt to "strangle" the harbor and other industrial development.

The slow trend in acceptance for the park also gained momentum in 1966 because of the approaching Congressional elections. While the port versus park issue had always split along partisan lines, this dichotomy was especially acute in 1966. The proposed Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore was perceived as a "Democratic" program. Senator Douglas himself was facing a tough re—election campaign against Republican challenger Charles Percy. United in favor of the park by the top Democrat in the White House, Indiana's five Democratic representatives used their influence to promote the park bill as did Democratic Governor Roger Branigan, and Democratic Senators Vance Hartke and Birch Bayh. With the opening of the second session of the 89th Congress, Senator Paul Douglas personally called on members of the House Interior committee to enlist their support. These collective efforts bore fruit. The favorable committee report came in July 1966.

Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey called committee members and Speaker of the House John McCormack to urge progress. President Lyndon B. Johnson, aware that polls indicated Douglas was trailing Percy, also called Speaker McCormack and reiterated his firm support for the park bill. Save the Dunes Council members joined with professional lobbyists representing labor, civil rights, and other liberal causes to promote the national lakeshore to each member of Congress.

On October 11, 1966, the park bill went before the Committee of the Whole. Throughout the afternoon and again the following morning, Charles Halleck, Joe Skubitz (Republican—Kansas), and Rogers C. B. Morton (Republican—Maryland) led a concentrated attack against H.R. 51. In its defense, Interior Committee Chairman Wayne Aspinall declared:

Exhaustive hearings were held by the National Parks and Recreation Subcommittee both in the field and in Washington. Every conceivable argument for and against the proposal was heard. I can honestly say no other park proposal has been given more intense consideration in this session of Congress than has been given H.R. 51.

Speaker John McCormack, polling for votes on the floor, discovered that the measure would fail if it came to a vote. Entire delegations were absent, back in their districts campaigning. In a cunning political move, McCormack proposed to House Minority Leader Charles Halleck that the park bill be rescheduled for later in the week in order that more important business be discussed. Believing that even more Democrats would be absent, thereby ensuring a humiliating defeat for the bill, Halleck readily agreed. The Indiana Dunes vote was postponed until Friday, October 14.

The brilliance of McCormack's move soon became apparent. One of the Great Society's pivotal programs was up for a vote on the same day. Ironically, Senator Paul Douglas' other bill, the Demonstration Cities and Metropolitan Development Act (or Model Cities Act) was scheduled for consideration. The White House had used every avenue to ensure that all Democrats would be in attendance. So, too, had the conservationists who launched a massive telegram drive. According to Save the Dunes Council member and President of the Indiana Division of the Izaak Walton League Thomas E. Dustin,

"If there is anything we could have done besides hiring a sky—writer to spell out "save the dunes" over the Capitol building, I don't know what it could be."

The proposed Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore reaped the benefits of the shrewd, top—level political maneuvering. On October 14, 1966, a legislative miracle occurred when the House of Representatives passed H.R. 51 with an impressive 204—141 vote. On October 18, the conference committee sent the bill back to the Senate which promptly concurred with the House amendments. Another irony involved the simultaneous approval of H.R. 50, which provided for an appropriation for Burns Harbor. The port versus park struggle, almost nine years in the making, had come to a draw.

The park bill, authorizing $28 million for 8,100 acres, went to 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue for President Johnson's signature. Indiana Dunes was not to become the first National Lakeshore, however, as President Johnson signed the Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore, Michigan, bill on October 15. Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore came into being on November 5, 1966, with the approval of Public Law 89—761. Signed into law at the LBJ Ranch in the Texas hill country, the President heralded the Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore Act as a great victory for the United States. A statement from the President, released by the Office of the White House Press Secretary from San Antonio, read:

The bill to establish the Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore has been 50 years in the making. In 1916, the National Park Service first cited the need to preserve for public use the strip of uninhabited, tree—covered dunes, and white sandy beaches stretching along the south shore of Lake Michigan from East Chicago to Michigan City.

Over the years many bills were introduced in the Congress. But it took the foresight and determination of the 89th Congress—and the tireless work of Senator Paul Douglas—to save the last remaining undeveloped portion of this lakeshore area. Thirteen miles of dunes and shoreline will be preserved for public use and enjoyment.

Its beaches and woodlands will provide a haven for the bird lover, the beachcomber, the botanist, the hiker, the camper, and the swimmer.

Within a 100—mile radius of the Indiana Dunes there are 9—1/2 million people crowded into one of the greatest industrial areas of our country. For these people, as well as for millions of other visitors, the Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore offer[s] ideal recreational opportunities. Here man can find solace and relief from the pressures of the industrial world.

The Members of Congress who have worked with dedication for so many years toward enactment of this bill deserve great credit. In addition to Senator Douglas, I particularly commend the diligence of Senators Hartke, and Bayh, and Representatives Roush, Madden, and Udall.

During the Administration more than 980,000 acres in 24 States have been added to the National Park System by the Congress. Twenty major conservation measures were passed by the 89th Congress. None gives me greater satisfaction than this bill to preserve the Indiana Dunes.

The great scenic and scientific attractions of the Dunes moved poet Carl Sandburg to say "the Indiana Dunes are to the Midwest what the Grand Canyon is to Arizona and Yosemite is to California."

Our entire country is made richer by this Act I have signed today.