Last updated: January 16, 2023

Person

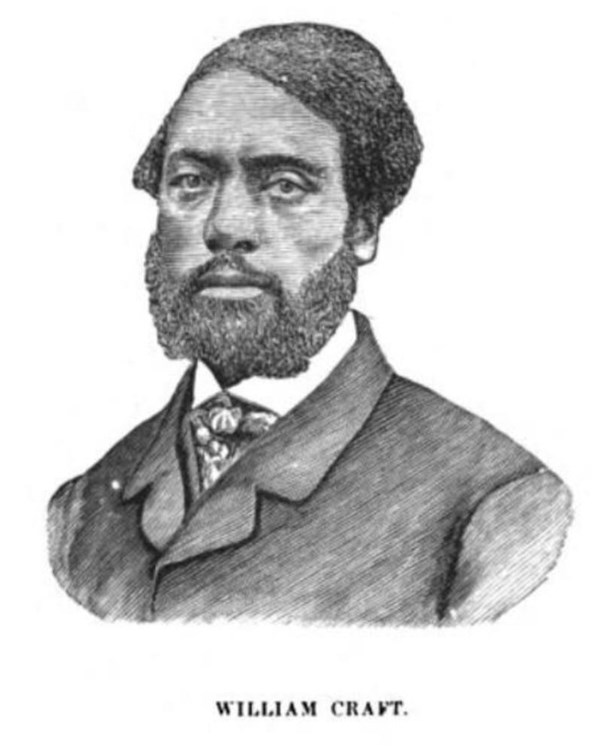

William Craft

Still's Underground Rail Road Records, William Still

Freedom seeker William Craft notably escaped slavery by acting as the enslaved man of his wife Ellen Craft, who disguised herself as a sickly, White gentleman.

Growing up enslaved in Georgia, Craft experienced the painful separation of his family. He recalled the irony that his enslaver "had the reputation of being a very humane and Christian man," however, "thought nothing of selling my poor old father, and dear aged mother, at separate times, to different persons, to be dragged off never to behold each other again."1 After selling Craft's parents, his enslaver sold three more of William's siblings. Due to his enslaver's financial issues, the bank took ownership of William (age 16) and his sister (age 14) and sent them to auction.2 Having been refused the opportunity to say goodbye to his sister, Craft recalled watching "tears trickling down her cheeks" as her enslaver took her away.3

While enslaved, William Craft worked as an apprentice to a cabinetmaker, building his craftsmanship skills that would help him later in life. Craft soon met Ellen Smith, an enslaved woman with lighter skin. Despite desiring freedom, they recognized the challenges that came with escaping and instead decided to get married and "settle down in slavery."4 Their plans changed in 1848 when William Craft devised a plan to escape. He proposed to his wife that due to her light skin color, she could dress as an ill, young, White planter, and he could play the role of the planter’s enslaved man. While Ellen Craft had her doubts, she agreed to use these disguises to escape to freedom.5

The Crafts began their journey to freedom on December 21, 1848. Upon leaving their home in Macon, Georgia, William Craft said to his wife, "Come my dear, let us make a desperate leap for liberty!"6 They traveled to Savannah, Georgia, and then made their way up the East Coast, taking various steamers and trains. When William Craft saw Philadelphia in the distance on Christmas morning, he recalled "I... felt that the straps that bound the heavy burden to my back began to pop, and the load to roll off."7 They rested a few weeks in Philadelphia at the home of abolitionists before continuing north to Boston.8

William and Ellen Craft joined the Black community in Boston's Beacon Hill, staying at Lewis and Harriet Hayden’s house. For the next two years, William worked as a cabinet-maker, opening his own shop at 51 Cambridge Street.9 Craft and his wife also participated in anti-slavery meetings, sharing their experiences and their story of their escape. However, the passage of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law threatened the Crafts' safety. In November of that year, two slave catchers successfully acquired a warrant to take the Crafts back into slavery. While abolitionists took Ellen Craft outside of the city, William Craft armed himself at his shop before going to the Haydens’ house. Years later, Craft notably recalled,

One night… Lewis Hayden and I had a keg of gunpowder under his house in Phillips Street [formerly Southac Street], with a fuse attached ready to light it should any attempt be made to capture us.10

Due to the efforts of the abolitionist community, the slave catchers left Boston. Realizing their freedom remained at risk, the Crafts decided to leave for England. Before their departure, their friend, Reverend Theodore Parker, remarried them "according to the laws of a free State."11

In England, William and Ellen Craft started their family while also continuing to advocate against slavery. They spoke at various events, including at the Great Exhibition in London, and also wrote about their escape in Thousand Miles for Freedom; Or the Escape of William and Ellen Craft from Slavery. During these years in England, newspapers document that William Craft frequently traveled to West Africa to encourage an end to the slave trade by "negotiating a commercial treaty with some of the chiefs on the western shores" as a representative of English merchants.12 According to The Liberator, in 1863 Craft left England to meet with the West African King of Dahomey to show him "the superior advantages of peaceful and legitimate commerce over the atrocious slave-trade with its concomitant barbarities."13

After the end of the American Civil War, William Craft and his family returned to Georgia. In 1873, they established the Woodville Co-operative Farm School to help newly emancipated men and women. Although initially successful, the Crafts had to shut down the school in the 1880s due to economic issues. William Craft and his wife lived the remaining years of their lives in Charleston, South Carolina with their daughter's family.14

Learn More...

"A Desperate Leap for Liberty": The Escape of William and Ellen Craft

Footnotes:

- William Craft, Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom; or, The Escape of William and Ellen Craft from Slavery (337 Strand, London: William Tweedie, 1860), https://archive.org/details/runningthousandm00craf/page/88/mode/2up?q=may, 9.

- Craft, Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom, 10-11

- Craft, Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom, 12

- Craft, Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom, 29.

- Craft, Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom, 29.

- Craft, Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom, 41.

- Craft, Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom, 79.

- For more information about the Craft’s escape to freedom, explore the story map: "A Desperate Leap for Liberty": The Escape of William and Ellen Craft.

- For more information about William Craft’s shop, see Site of William Craft’s Shop.

- Vincent Yardley Bowditch, Life and Correspondence of Henry Ingersoll Bowditch (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1902), https://archive.org/details/lifecorresponden02bowd/page/n399/mode/2up?q=craft, 373.

- William Still, Still's Underground Rail Road Records: With a Life of the Author. Narrating the Hardships, Hairbreadth Escapes and Death Struggles of the Slaves in Their Efforts for Freedom (United States: William Still, 1886), https://www.google.com/books/edition/Still_s_Underground_Rail_Road_Records/KD9LAAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&printsec=frontcover, 371.

- "A Notable Case. Libel Suit of William Craft Against Naylor & Co.," Boston Daily Advertiser, June 6, 1878, Genealogybank.

- "Dahomey," The Liberator (Boston, Massachusetts), February 20, 1863, Genealogybank.

- Barbara McCaskill, "William and Ellen Craft (1824-1900; 1826-1891)," New Georgia Encyclopedia, July 16, 2020, accessed March 2021, https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/history-archaeology/william-and-ellen-craft-1824-1900-1826-1891.