NPS photo. Plate Tectonics: The Birth of PinnaclesTo understand how Pinnacles National Park originated, imagine watching a time-lapse video that spans the past 60 million years, all the way to the present. As you fast-forward through this geological history, you witness the dramatic transformation of the landscape, revealing the story of Pinnacles. The Beginnings: A Changing EarthWhen the video starts, the continents resemble their current forms. Most of the world’s great mountain ranges are already in place, but the Pacific Ocean extends much farther inland, and many of California’s coastal mountains have yet to rise. These mountains, however, are on the brink of formation—thanks to the powerful forces of plate tectonics. The movement of the Earth’s tectonic plates, including the interaction of the Pacific Plate and the North American Plate, sets the stage for the creation of the landscape we now know as Pinnacles National Park.

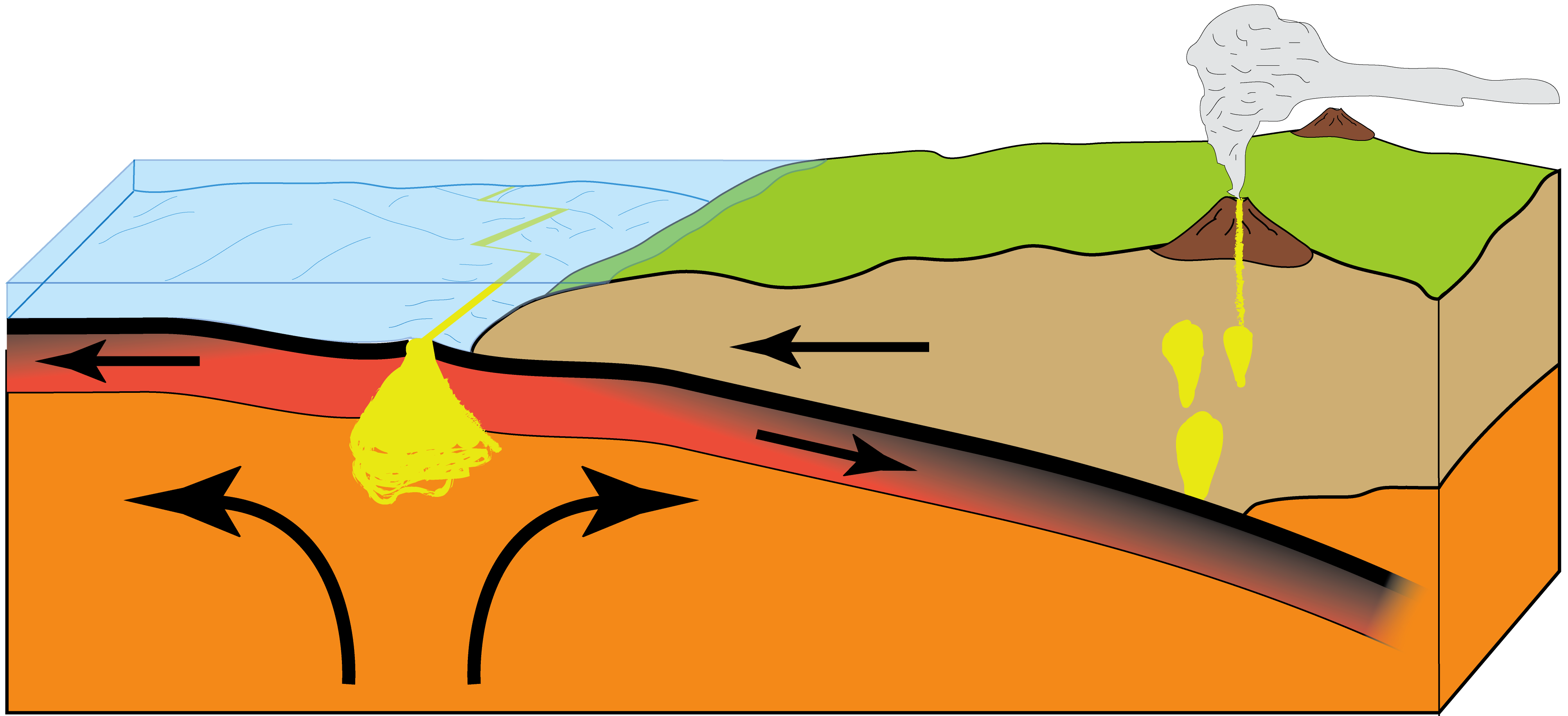

The Formation of the Coast Range: Plate Tectonics at WorkGeologists believe that the Earth’s crust is divided into immense plates that fit together like pieces of a giant jigsaw puzzle. These plates are constantly in motion, mostly shifting horizontally. According to geologic theory, plates interact in at least three ways, and two are significant to the formation of Pinnacles: subduction zones, where one plate moves beneath another, and transform boundaries, where plates slide past each other. Around 60 million years ago, when our geological "video" begins, the lighter-weight North American Plate began to override, or subduct, the denser Farallon Plate. As this occurred, the outer edge of the North American Plate acted like a bulldozer, scooping up enormous amounts of seafloor sediment. Over time, this sediment accumulated, forming a series of north-south ridges. These rows of mountainous rubble eventually became the Coast Range, stretching like parallel pleats along much of California’s western edge.

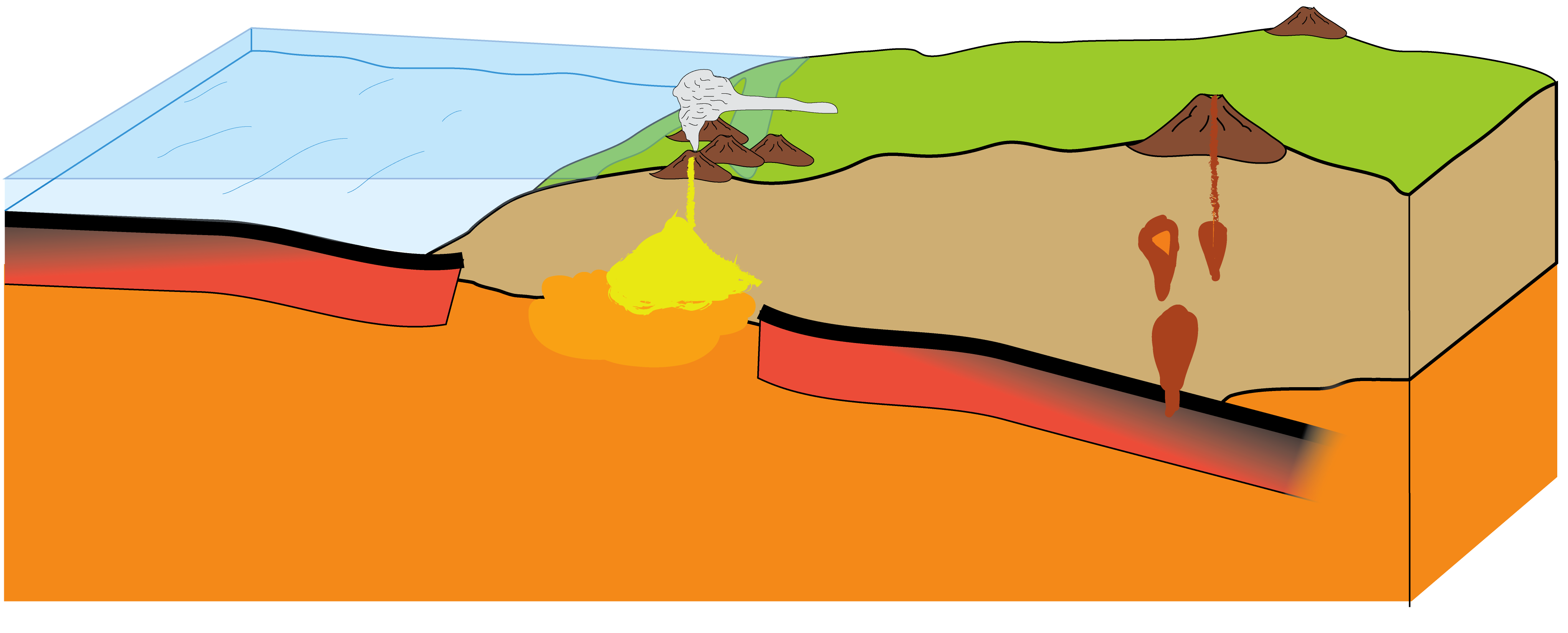

The Pinnacles Volcanic FieldBut all was not peaceful in the depths of the earth. The subducted Farallon plate pushed ever under and downward, began melting, and as the two plates continued colliding, the tension cracks and fissures that formed were ready releases for the molten rock below. Time and again the magma made its way upward -- sometimes flowing out like hot taffy, other times spewing forth in frenzied conflagrations. In some places the magma seeped into vertical cracks and hardened as a dike or wall. In other places it made its way along horizontal fissures to form a sort of underground lake which eventually solidified as a sill. Whatever the molten material’s form, one fact was certain: the age of volcanism had arrived.

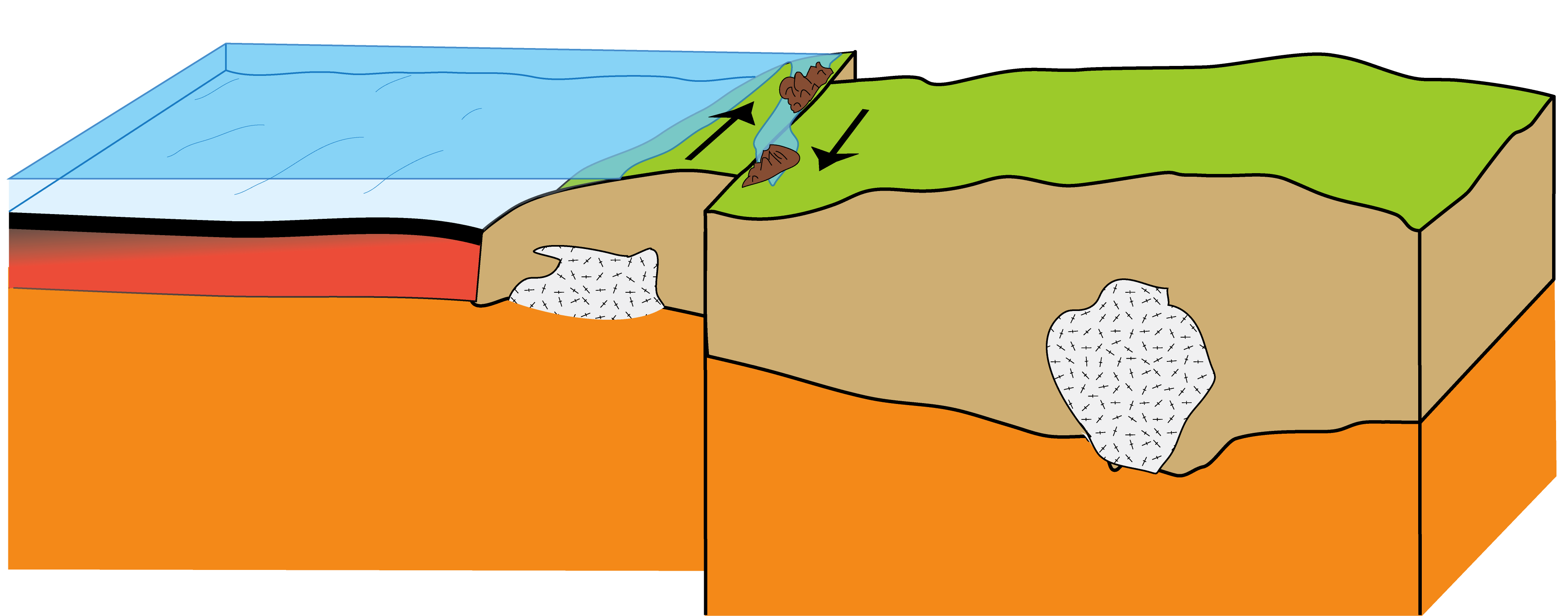

Movement Along the FaultNo one can say for sure exactly when the Pinnacles volcanic field came into existence, though scientists estimate that it was twenty-two to twenty-three million years ago. What they can say with some certainty is that it began near Lancaster in Southern California. In the scheme of things, this volcanic field was nothing extraordinary. Like most of its counterparts, it began slowly, building itself up in stages that alternated between blazing pyroclastics, viscous oozes, and seeming dormancy. Multiple eruptions from multiple volcanoes created layer upon layer of volcanic rock.Once the Farallon plate had been completely overridden, subduction ended. With no more magma to fuel them, the coastal volcanoes dried up and began eroding. But all was still not quiet in the tectonic zone. For right behind the Farallon plate was the Pacific plate, and rather than being subducted like its predecessor, it ground against the North American plate’s western edge until a small portion of the American plate snapped along the stress lines and became attached to the Pacific plate’s upper edge. A transform boundary had come into being. And so has the San Andreas Fault zone, a crack in the earth that stretched more than six hundred miles from the Gulf of California to the Mendocino coast north of San Francisco. Directly in its path, and now astride the two plates, was the Pinnacles volcanic field. As the newly broken sliver of California began its strike-slip displacement journey northwest, thanks to the movement of the Pacific plate, it took with it two-thirds of the Pinnacles’ volcanic mass. Pinnacles now lies 195 miles north of its birthplace near Los Angeles, CA. The journey is far from over, however, as the San Andreas Fault zone continues to slip at a rate of 1 inch/year. ErosionSomewhere along the way, the partial volcanic field -- trapped between the San Andreas on one side and a lesser fault (now called the Pinnacles fault) on the other -- began sinking downward until most of its bulk lay in a graben or ditch where it was protected by the fault-line ramparts rising high above it. In time the ramparts eroded, exposing Pinnacles to the full fury of wind, rain, and ice.Thousands of feet of overlying rubble gradually wore away. Steep ravines developed; monoliths and colonnades took their place beside massive walls and lonely pillars; boulders fell from lofty recesses to overtop narrow stream channels. It was a world of gentle canyons and fractured ridges, breathtaking vistas and eerie silence, glowing colors and inhospitable soil. But most of all, it was young while it was old, for Pinnacles was forever rearranging its features, changing the face fashioned yesterday and creating a new tomorrow. To learn how Pinnacles geology fits in with other national parks in the area, visit the San Francisco Bay Area Network geology page. |

Last updated: October 18, 2024