Last updated: November 28, 2023

Place

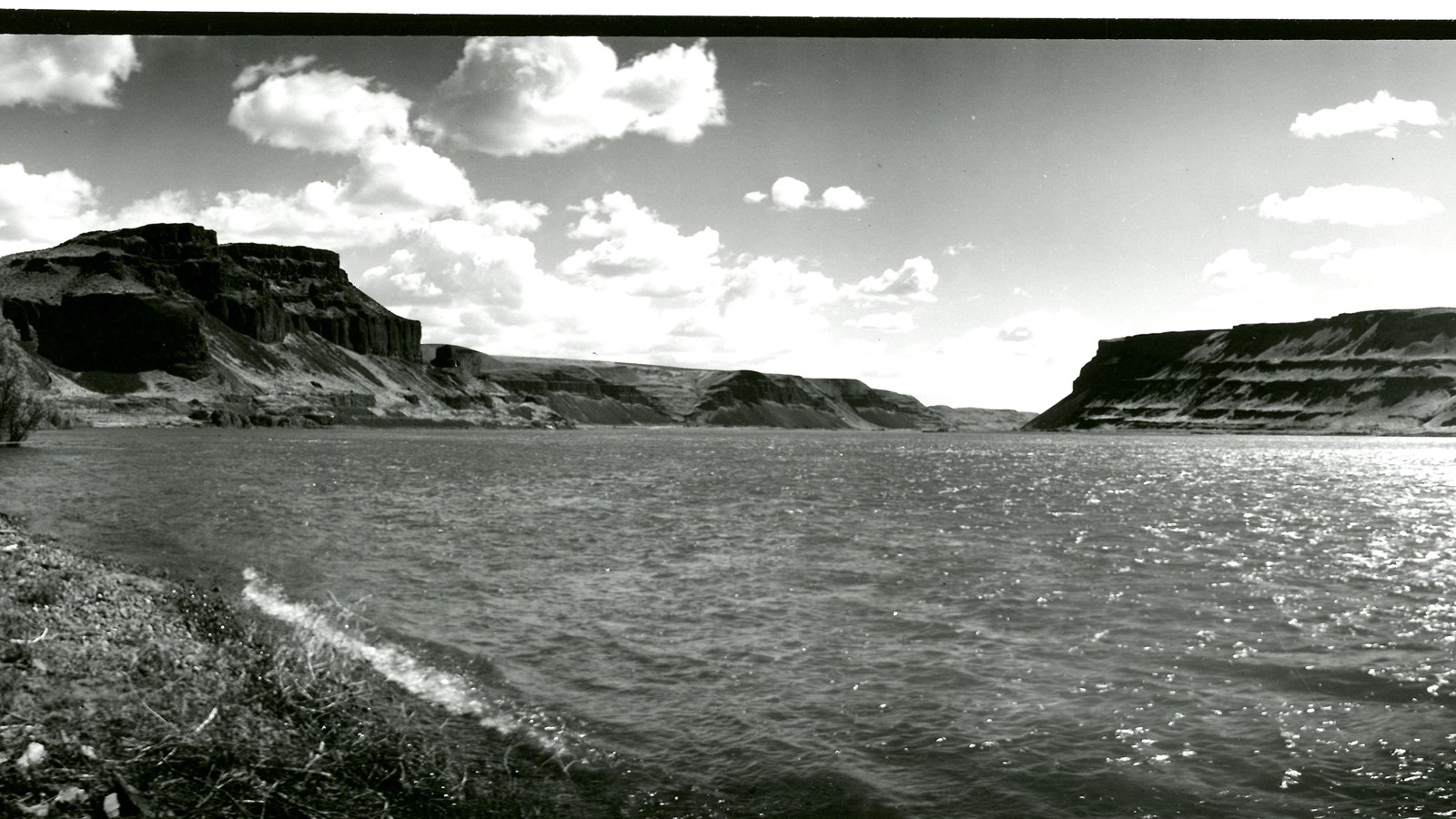

Confluence of the Columbia and Walla Walla Rivers

John J. Arnold, 1940, Spokane Public Library

Historical/Interpretive Information/Exhibits, Information Kiosk/Bulletin Board, Parking - Auto, Picnic Table

Lewis and Clark NHT Visitor Centers and Museums

This map shows a range of features associated with the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail, which commemorates the 1803-1806 Lewis and Clark Expedition. The trail spans a large portion of the North American continent, from the Ohio River in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to the mouth of the Columbia River in Oregon and Washington. The trail is comprised of the historic route of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, an auto tour route, high potential historic sites (shown in black), visitor centers (shown in orange), and pivotal places (shown in green). These features can be selected on the map to reveal additional information. Also shown is a base map displaying state boundaries, cities, rivers, and highways. The map conveys how a significant area of the North American continent was traversed by the Lewis and Clark Expedition and indicates the many places where visitors can learn about their journey and experience the landscape through which they traveled.

Many Indigenous people lived along the Columbia River seasonally. They would travel to their family’s regular fishing spot when the salmon were running, or when the weather was too frigid in the high country. For Sahaptian-speaking residents of the Columbia River Plateau, including the Umatilla, Cayuse, Yakama, and Walla Walla people, fishing for salmon was and is a way of life and of obtaining sustenance. It was and continues to be spiritually and culturally important.

William Clark’s sketch of the confluence of the Walla Walla and Columbia Rivers noted so many times the “lodges of Indians fishing.” The expedition passed through at a time when the salmon were swimming upstream—everyone was down at their fishing spot. Bobbie Conner, director of the Tamástslikt Cultural Institute on the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Reservation, explained,

Sahaptian-speaking people fishing here welcomed these distant visitors. Many probably knew the Nez Perce men, Walamottinin (Twisted Hair) and Tetoharsky, who were traveling with them. They sold the visitors dogs—dozens of dogs that the expedition members then killed and ate. The locals wondered why these men would rather eat dogs than the delicious salmon that were spawning.

On the party’s journey upstream the following year, another man who lived in the region and knew the river well accompanied the travelers. In exchange for the ride, he helped the party decide which villages to visit. Communities on the river looked very different in April 1806 than they had in October 1805, but more salmon were about to arrive, and things would soon change yet again.

The travelers first met Yelépt, a Wallulapum leader in 1805. He hosted the party for several days at his village on the visitors’ journey downstream in the fall and then upstream in the spring. They socialized, sang, danced, and rested. They traded canoes and horses and Yelépt helped them prepare for the upstream journey.

Fishing for salmon along the Columbia has long been a way of life for Indigenous people of the Columbia River Plateau. That continues to this day, despite the dams that have made it harder for the salmon to make their way upstream.

About this article: This article is part of a series called “Pivotal Places: Stories from the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail.”