Last updated: July 14, 2023

Place

Springwells

Rusty Davis

Quick Facts

Location:

6325 W Jefferson Ave, Detroit, MI 48209

MANAGED BY:

Detroit Parks and Recreation Division

Amenities

20 listed

Accessible Rooms, Accessible Sites, Benches/Seating, Bicycle - Rack, Entrance Passes for Sale, Historical/Interpretive Information/Exhibits, Information, Information Kiosk/Bulletin Board, Parking - Auto, Parking - Boat Trailer, Parking - Bus/RV, Picnic Table, Playground, Restroom, Restroom - Accessible, Scenic View/Photo Spot, Toilet - Flush, Trailhead, Trash/Litter Receptacles, Wheelchair Accessible

SPRINGWELLS

Arguably one of the most historic sites in the State of Michigan, the Springwells site has deep cultural significance going back more than a millennium to the area’s first native inhabitants. From Woodland times (400-1200 CE) through the War of 1812 and up to the present, Springwells has been a central and integral component of the cultural mosaic and evolving landscape on the Detroit.

Springwells, now referred to as Historic Fort Wayne, is located just south of the city of Detroit. The freshwater springs located behind the sandy bluff at Springwells attracted long-term indigenous settlements and served as a major burial site dating from the Woodland period (400 CE -1200 CE) up through the early 1800s.

Earthworks

Researchers suggest that the Springwells’ earthworks along the riverside bluff ranged from six to as many as nineteen mounds. The earthworks stretched from the mouth of the River Rouge downstream, along the northern shoreline of the Detroit River and upstream, to an area due east of the Fort. The presence of a large group of burial mounds, within such a small area, suggests that the Springwells Mound Group was an important ceremonial context in southeastern Michigan for much of the 1st millennium CE.

Historical accounts suggest that on the eve of the War of 1812, the Springwells area continued to function as an important burial site, drawing Native people of the Great Lakes to the earthworks for mortuary ceremonies and to live. The springs were close to river bottomlands for seasonal cultivation and to nearby forest areas for hunting and gathering year-round. In front of the bluff at Springwells flowed the Detroit River, which offered nearby marshes, rich fishing sites, and access to communication and transportation routes throughout the Great Lakes region.

First Shot Fired of the War of 1812

Michigan Territorial Governor William Hull was appointed the new General of the Northwest Army in preparation for war in 1812. Knowing that Detroit was isolated, one of Hull’s first challenges was to build a military supply road from Ohio to Detroit. Starting in late May near Dayton Ohio, Hull and his soldiers moved north building a corduroy road and reached the Maumee River in present-day Toledo, Ohio in late June. While at the Maumee River, General Hull secured a boat to send supplies and some sick soldiers across western Lake Erie to Detroit, not realizing that war was declared. The British, already learning that war was declared captured the boat, seizing the supplies and sick soldiers.

On July 5, 1812, as General Hull approached Springwells, just south of Fort Detroit, he heard the distinct sound of artillery fire a few miles north in the vicinity of Detroit despite of his orders received three days prior from the Secretary of War William Eustis, informing him that War had been declared against the British but to await further orders before proceeding with the planned invasion. As Hull approached the Springwells, he learned his men fired the first artillery shots of the War of 1812 from this site into British Canada on the other side of the Detroit River.

General Hull immediately ordered the construction of floating batteries in order to bombard and burn Amherstburg downstream closer to Lake Erie and additional batteries to be erected at Springwells, opposite Sandwich in preparation for an invasion of Canada. Hull sent Colonel Lewis Cass from Springwells across the river and downstream to Fort Malden (Amherstburg) with a flag of truce to request the return of baggage and prisoners captured by the British. Hull’s message to British Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas St. George included an apology: “Sir, since the arrival of my army at this Encampment (five o’clock P M yesterday) I have been informed that a number of discharges of Artillery and of small arms have been made by some of the Militia of the Territory, from this Shore [Springwells] into Sandwich, I regret to have received such information, the proceeding was not authorized by me.” Despite an apologetic tone, Hull’s request for the return of baggage and prisoners was refused. Cass was blindfolded and escorted back to the encampment at Springwells. With Cass’s subsequent return to Detroit, antagonism grew on both banks of the Detroit River.

General Hull decided to establish a military encampment at Springwells. The location was ideal for a military encampment because the sandy bluffs created a better elevation, its closer to Canada than Fort Detroit, and was long considered a superior location for the defense of Detroit. On July 7th, five additional artillery pieces were brought from the Fort in Detroit to Springwells and placed on the riverbank in front of the military encampment to fire on the enemy at Sandwich and the U.S. Infantry marched from Springwells to Detroit.

Invasion of Canada

On July 8, 1812, the Ohio militia, who were camped at Springwells, marched to Detroit. The next day, General Hull received discretionary orders allowing him to invade the British in Upper Canada. According to Captain McAfee, “on the evening of 11th, the regiment of Colonel M’Arthuer, accompanied by some boats, was marched down to the Springwells, to decoy the enemy.” As Hull prepared to invade Canada, 200 Ohio Militiamen suddenly refused to go, stating that they could not serve outside the American territory. On July 12th, Hull’s army, weakened by the absence of 200 Ohioans, crossed over the Detroit River by way of Hog Island (Belle Isle) and landed in Canada unopposed. The British had evacuated Sandwich (“D” on the July 1812 map) to Ft. Malden hours before Hull’s invasion. Hull marched further down river to Sandwich and issued a proclamation to the inhabitants of Canada promising to protect them, urging their militiamen to abandon the British, and warning them that if they fought alongside the Native Warriors, they would experience a “war of extermination… No white man found fighting by the side of an Indian, will be taken prisoner. Instant destruction will be his lot.”

Surrender of Detroit

August 15, 1812 10:00 a.m.: British officers crossed the river to Detroit under a flag of truce carrying General Brock's demand for General Hull to surrender. Brock threatened that if Hull did not surrender, “uncontrollable” Native warriors would destroy the entire settlement. Hull ordered a council with his officers during which time he sent another messenger inquiring about the return of Colonel Duncan McArthur with the River Raisin expedition back to Detroit.

Native Confederation forces, led by Shawnee War Chief Tecumseh and the Mohawk War Chief John Norton (Teyoninhokarawen), left Amherstburg by canoe early on August 15th planning to disembark at Brownstown and to move north to Detroit along the American side of the river. Instead, Tecumseh and his forces paddled directly to Sandwich on the Canadian side, avoiding a difficult walk across the marshlands below the Rouge River, to assemble with Brock at Sandwich directly across from the open bluff at Springwells.

August 15, 1812 3:00 p.m.: Following the officer council, Hull brashly responded to General Brock’s threat, despite his troop losses in previous ambushes and shortage of soldiers, since his detachment had not returned. Hull refused to surrender in hopes that his errant forces would arrive and come to his aid: “I am ready to meet any force which may be at your disposal, and any consequences which may result from its execution in any way you may think proper to use it…”

August 15, 1812 evening: After Hull’s response reached General Brock, the British vessels Queen Charlotte and General Hunter moved closer to bombard Fort Detroit and its batteries. The British began to fire upon soft targets within the Fort, opening weak spots for Native Warriors to infiltrate the Fort, which was densely packed with women and children seeking safety. Portions of the Fort were set on fire and some civilians were killed. No U.S artillery could fire south or west towards the British at May’s Creek, because it was too far, and the views were obscured by trees, houses and fences.

During the evening, American Brigade Major Jessup, Major Taylor, Captain Snelling and Quartermaster Dugan “rode down the river [the short distance] to Springwells to view the enemy at Sandwich” and the “position of the Queen Charlotte,” concluding “that the enemy intended to effect a landing at that place” (McAfee 1816). Springwells was the most logical location for the British invasion as it was the narrowest river crossing and out of range of the American guns at Detroit. It was also on an open sandy bluff below the ribbon farms and above the marsh at the Rouge in an open area suitable for assembling and moving troops after crossing the river.

That same night, Native Warriors crossed the river and landed at Springwells. They then advanced along the western edge of the woods bordering the farmlands below the Fort. The Confederation Warriors moved undetected about 1 mile west from the shoreline as they surrounded the Fort.

August 16, 1812: On the morning of August 16th, with ample cover fire from British batteries on the opposite shore and from the British ships the Queen Charlotte and the General Hunter anchored on the river about a half-mile above Sandwich, General Brock led the British across the Detroit River to Springwells unopposed. They marched just north to May’s Creek and setup a defensive position along the ravine.

General Hull was confronted with a dilemma: lacking supplies, no reinforcements coming from River Raisin, situated within range of British guns, surrounded by Native Warriors, and General Brock positioned just outside of his artillery range, and a large civilian population. General Hull made the decision to capitulate. He hoisted a white flag and sent an officer out to meet General Brock. Brock had advanced to within twelve hundred yards of the Fort and was preparing to storm the walls, when he saw the American coming to make terms. Fort Detroit was subsequently surrendered and placed under British control. About 2,500 Americans soldiers were taken as prisoners of war and marched to British Canada. After securing Detroit, Native Warriors and British Soldiers proceeded to the River Raisin and took control of Frenchtown.

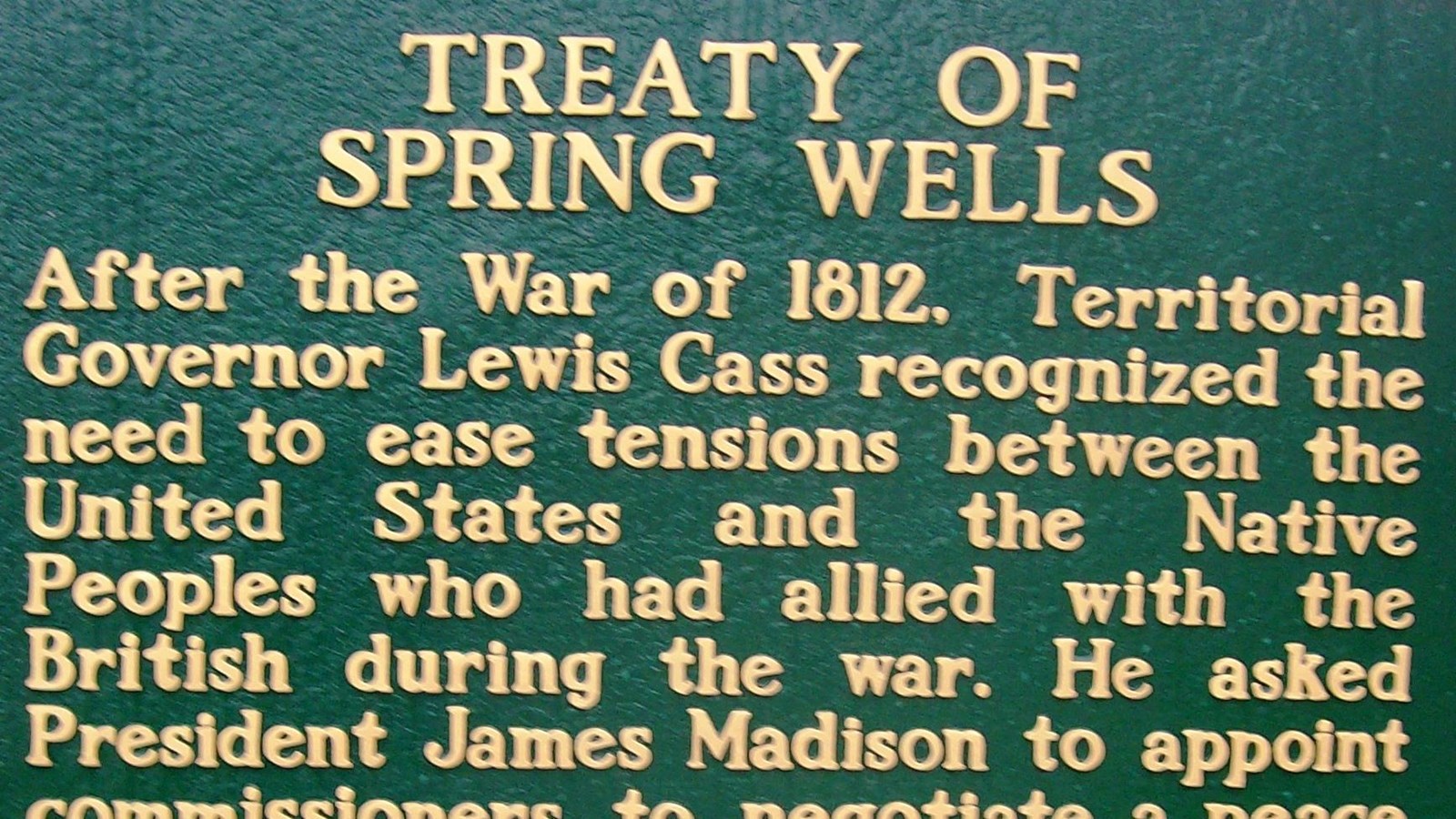

Treaty of Springwells,1814

On December 24th, 1814, the Treaty of Ghent finally ended the war between the United States and Great Britain. The British had attempted to secure an independent Indian State for the Tribal Nations in the Great Lakes during negotiations, but the United States refused. The Treaty of Ghent did obligate the United States to cease “hostilities with all the Tribes or Nations of Indians with whom they may be at war at the time of such Ratification, and forthwith to restore to such Tribes or Nations respectively all the possessions, rights, and privileges which they may have enjoyed or been entitled to in one thousand eight hundred and eleven previous to such hostilities (Treaty of Ghent 1814)". Nearly six months after the Treaty of Ghent was signed, the Great Lakes Native people stated that no treaty of Peace had taken place between them and the United States and “no measures had been taken to remove the original cause of hostilities”. Without a representative at the signing of the Treaty of Ghent, the Native Nations believed that "they were as much at War at this time as they have been during the whole contest.”

Lacking a Treaty recognized by the Native Nations to end the War of 1812, Native leaders, American military, and territorial officials, gathered once again on the bluff at Springwells below Detroit on September 8, 1815, to officially end hostilities. Against the backdrop of Springwells’ Woodland Period burial mounds and by the sacred spring, General William Henry Harrison, territorial officials and the leaders of eight Native Nations (Chippewa, Delaware, Miami, Ottawa, Potawatomi, Shawnee, Seneca and Wyandot) met to negotiate peace. The treaty terms absolved Native warriors for their part in the War of 1812 and placed them under the protection of the U.S. government, as the Treaty of Ghent had tried to accomplish nearly nine months prior. Tribal signatories were pardoned for their actions during the war and the U.S. agreed to restore Native possessions, rights, and privileges as of 1811. In effect, like the Treaty of Ghent, the Treaty of Springwells called for returning to the pre-war boundaries and agreements. Once signed, the Treaty of Springwells officially ends the War of 1812 and hostilities between the U.S. and the assembled Native Nations.

After the War of 1812

Following the War of 1812, Springwells drew additional attention for its strategic location on the Detroit riverfront. In 1815, newly promoted Brigadier General Duncan McArthur again suggested, “At Spring Well (sic), there is a natural position which completely commands the surrounding country and river for several miles”. During the implementation of “Indian Removal” in the aftermath of the River Raisin, Springwells functioned as a military encampment where local militias held meetings to support the 1832 Black Hawk War. Fears on both sides of the border that political turmoil among factions in Canada and supporters in the U.S. would erupt into another international conflict further intensified with “Indian Removal” and the Patriots War of 1837 that briefly resulted in some U.S. forces entering British Canada. By 1843, with continuing concerns over future disputes with Canada and fears of another British invasion like the one that crippled the United States at the River Raisin in 1813, construction of a massive fort at Springwells finally began. Christened Fort Wayne after General “Mad” Anthony Wayne, the star-shaped fort was built on the strategic flat sandy bluff overlooking the north bank of the river adjacent to the springs, largely displacing the remaining Woodland burial mounds.

PLAN YOUR VISIT Location: Historic Fort Wayne 6325 West Jefferson Avenue Detroit, MI 48209, Phone: 734-324-7295 Hours: 6:00 a.m. to 10:00 p.m. Admission Fee: YES

THINGS TO DO Parking: Parking Lot available River Access: River View Only Trail Access: Onsite Walking Paths

Passport Stamp: NO

Guided Tours available by the Historic Fort Wayne Coalition. To make reservations call 313-628-0796.

Arguably one of the most historic sites in the State of Michigan, the Springwells site has deep cultural significance going back more than a millennium to the area’s first native inhabitants. From Woodland times (400-1200 CE) through the War of 1812 and up to the present, Springwells has been a central and integral component of the cultural mosaic and evolving landscape on the Detroit.

Springwells, now referred to as Historic Fort Wayne, is located just south of the city of Detroit. The freshwater springs located behind the sandy bluff at Springwells attracted long-term indigenous settlements and served as a major burial site dating from the Woodland period (400 CE -1200 CE) up through the early 1800s.

Earthworks

Researchers suggest that the Springwells’ earthworks along the riverside bluff ranged from six to as many as nineteen mounds. The earthworks stretched from the mouth of the River Rouge downstream, along the northern shoreline of the Detroit River and upstream, to an area due east of the Fort. The presence of a large group of burial mounds, within such a small area, suggests that the Springwells Mound Group was an important ceremonial context in southeastern Michigan for much of the 1st millennium CE.

Historical accounts suggest that on the eve of the War of 1812, the Springwells area continued to function as an important burial site, drawing Native people of the Great Lakes to the earthworks for mortuary ceremonies and to live. The springs were close to river bottomlands for seasonal cultivation and to nearby forest areas for hunting and gathering year-round. In front of the bluff at Springwells flowed the Detroit River, which offered nearby marshes, rich fishing sites, and access to communication and transportation routes throughout the Great Lakes region.

First Shot Fired of the War of 1812

Michigan Territorial Governor William Hull was appointed the new General of the Northwest Army in preparation for war in 1812. Knowing that Detroit was isolated, one of Hull’s first challenges was to build a military supply road from Ohio to Detroit. Starting in late May near Dayton Ohio, Hull and his soldiers moved north building a corduroy road and reached the Maumee River in present-day Toledo, Ohio in late June. While at the Maumee River, General Hull secured a boat to send supplies and some sick soldiers across western Lake Erie to Detroit, not realizing that war was declared. The British, already learning that war was declared captured the boat, seizing the supplies and sick soldiers.

On July 5, 1812, as General Hull approached Springwells, just south of Fort Detroit, he heard the distinct sound of artillery fire a few miles north in the vicinity of Detroit despite of his orders received three days prior from the Secretary of War William Eustis, informing him that War had been declared against the British but to await further orders before proceeding with the planned invasion. As Hull approached the Springwells, he learned his men fired the first artillery shots of the War of 1812 from this site into British Canada on the other side of the Detroit River.

General Hull immediately ordered the construction of floating batteries in order to bombard and burn Amherstburg downstream closer to Lake Erie and additional batteries to be erected at Springwells, opposite Sandwich in preparation for an invasion of Canada. Hull sent Colonel Lewis Cass from Springwells across the river and downstream to Fort Malden (Amherstburg) with a flag of truce to request the return of baggage and prisoners captured by the British. Hull’s message to British Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas St. George included an apology: “Sir, since the arrival of my army at this Encampment (five o’clock P M yesterday) I have been informed that a number of discharges of Artillery and of small arms have been made by some of the Militia of the Territory, from this Shore [Springwells] into Sandwich, I regret to have received such information, the proceeding was not authorized by me.” Despite an apologetic tone, Hull’s request for the return of baggage and prisoners was refused. Cass was blindfolded and escorted back to the encampment at Springwells. With Cass’s subsequent return to Detroit, antagonism grew on both banks of the Detroit River.

General Hull decided to establish a military encampment at Springwells. The location was ideal for a military encampment because the sandy bluffs created a better elevation, its closer to Canada than Fort Detroit, and was long considered a superior location for the defense of Detroit. On July 7th, five additional artillery pieces were brought from the Fort in Detroit to Springwells and placed on the riverbank in front of the military encampment to fire on the enemy at Sandwich and the U.S. Infantry marched from Springwells to Detroit.

Invasion of Canada

On July 8, 1812, the Ohio militia, who were camped at Springwells, marched to Detroit. The next day, General Hull received discretionary orders allowing him to invade the British in Upper Canada. According to Captain McAfee, “on the evening of 11th, the regiment of Colonel M’Arthuer, accompanied by some boats, was marched down to the Springwells, to decoy the enemy.” As Hull prepared to invade Canada, 200 Ohio Militiamen suddenly refused to go, stating that they could not serve outside the American territory. On July 12th, Hull’s army, weakened by the absence of 200 Ohioans, crossed over the Detroit River by way of Hog Island (Belle Isle) and landed in Canada unopposed. The British had evacuated Sandwich (“D” on the July 1812 map) to Ft. Malden hours before Hull’s invasion. Hull marched further down river to Sandwich and issued a proclamation to the inhabitants of Canada promising to protect them, urging their militiamen to abandon the British, and warning them that if they fought alongside the Native Warriors, they would experience a “war of extermination… No white man found fighting by the side of an Indian, will be taken prisoner. Instant destruction will be his lot.”

Surrender of Detroit

August 15, 1812 10:00 a.m.: British officers crossed the river to Detroit under a flag of truce carrying General Brock's demand for General Hull to surrender. Brock threatened that if Hull did not surrender, “uncontrollable” Native warriors would destroy the entire settlement. Hull ordered a council with his officers during which time he sent another messenger inquiring about the return of Colonel Duncan McArthur with the River Raisin expedition back to Detroit.

Native Confederation forces, led by Shawnee War Chief Tecumseh and the Mohawk War Chief John Norton (Teyoninhokarawen), left Amherstburg by canoe early on August 15th planning to disembark at Brownstown and to move north to Detroit along the American side of the river. Instead, Tecumseh and his forces paddled directly to Sandwich on the Canadian side, avoiding a difficult walk across the marshlands below the Rouge River, to assemble with Brock at Sandwich directly across from the open bluff at Springwells.

August 15, 1812 3:00 p.m.: Following the officer council, Hull brashly responded to General Brock’s threat, despite his troop losses in previous ambushes and shortage of soldiers, since his detachment had not returned. Hull refused to surrender in hopes that his errant forces would arrive and come to his aid: “I am ready to meet any force which may be at your disposal, and any consequences which may result from its execution in any way you may think proper to use it…”

August 15, 1812 evening: After Hull’s response reached General Brock, the British vessels Queen Charlotte and General Hunter moved closer to bombard Fort Detroit and its batteries. The British began to fire upon soft targets within the Fort, opening weak spots for Native Warriors to infiltrate the Fort, which was densely packed with women and children seeking safety. Portions of the Fort were set on fire and some civilians were killed. No U.S artillery could fire south or west towards the British at May’s Creek, because it was too far, and the views were obscured by trees, houses and fences.

During the evening, American Brigade Major Jessup, Major Taylor, Captain Snelling and Quartermaster Dugan “rode down the river [the short distance] to Springwells to view the enemy at Sandwich” and the “position of the Queen Charlotte,” concluding “that the enemy intended to effect a landing at that place” (McAfee 1816). Springwells was the most logical location for the British invasion as it was the narrowest river crossing and out of range of the American guns at Detroit. It was also on an open sandy bluff below the ribbon farms and above the marsh at the Rouge in an open area suitable for assembling and moving troops after crossing the river.

That same night, Native Warriors crossed the river and landed at Springwells. They then advanced along the western edge of the woods bordering the farmlands below the Fort. The Confederation Warriors moved undetected about 1 mile west from the shoreline as they surrounded the Fort.

August 16, 1812: On the morning of August 16th, with ample cover fire from British batteries on the opposite shore and from the British ships the Queen Charlotte and the General Hunter anchored on the river about a half-mile above Sandwich, General Brock led the British across the Detroit River to Springwells unopposed. They marched just north to May’s Creek and setup a defensive position along the ravine.

General Hull was confronted with a dilemma: lacking supplies, no reinforcements coming from River Raisin, situated within range of British guns, surrounded by Native Warriors, and General Brock positioned just outside of his artillery range, and a large civilian population. General Hull made the decision to capitulate. He hoisted a white flag and sent an officer out to meet General Brock. Brock had advanced to within twelve hundred yards of the Fort and was preparing to storm the walls, when he saw the American coming to make terms. Fort Detroit was subsequently surrendered and placed under British control. About 2,500 Americans soldiers were taken as prisoners of war and marched to British Canada. After securing Detroit, Native Warriors and British Soldiers proceeded to the River Raisin and took control of Frenchtown.

Treaty of Springwells,1814

On December 24th, 1814, the Treaty of Ghent finally ended the war between the United States and Great Britain. The British had attempted to secure an independent Indian State for the Tribal Nations in the Great Lakes during negotiations, but the United States refused. The Treaty of Ghent did obligate the United States to cease “hostilities with all the Tribes or Nations of Indians with whom they may be at war at the time of such Ratification, and forthwith to restore to such Tribes or Nations respectively all the possessions, rights, and privileges which they may have enjoyed or been entitled to in one thousand eight hundred and eleven previous to such hostilities (Treaty of Ghent 1814)". Nearly six months after the Treaty of Ghent was signed, the Great Lakes Native people stated that no treaty of Peace had taken place between them and the United States and “no measures had been taken to remove the original cause of hostilities”. Without a representative at the signing of the Treaty of Ghent, the Native Nations believed that "they were as much at War at this time as they have been during the whole contest.”

Lacking a Treaty recognized by the Native Nations to end the War of 1812, Native leaders, American military, and territorial officials, gathered once again on the bluff at Springwells below Detroit on September 8, 1815, to officially end hostilities. Against the backdrop of Springwells’ Woodland Period burial mounds and by the sacred spring, General William Henry Harrison, territorial officials and the leaders of eight Native Nations (Chippewa, Delaware, Miami, Ottawa, Potawatomi, Shawnee, Seneca and Wyandot) met to negotiate peace. The treaty terms absolved Native warriors for their part in the War of 1812 and placed them under the protection of the U.S. government, as the Treaty of Ghent had tried to accomplish nearly nine months prior. Tribal signatories were pardoned for their actions during the war and the U.S. agreed to restore Native possessions, rights, and privileges as of 1811. In effect, like the Treaty of Ghent, the Treaty of Springwells called for returning to the pre-war boundaries and agreements. Once signed, the Treaty of Springwells officially ends the War of 1812 and hostilities between the U.S. and the assembled Native Nations.

After the War of 1812

Following the War of 1812, Springwells drew additional attention for its strategic location on the Detroit riverfront. In 1815, newly promoted Brigadier General Duncan McArthur again suggested, “At Spring Well (sic), there is a natural position which completely commands the surrounding country and river for several miles”. During the implementation of “Indian Removal” in the aftermath of the River Raisin, Springwells functioned as a military encampment where local militias held meetings to support the 1832 Black Hawk War. Fears on both sides of the border that political turmoil among factions in Canada and supporters in the U.S. would erupt into another international conflict further intensified with “Indian Removal” and the Patriots War of 1837 that briefly resulted in some U.S. forces entering British Canada. By 1843, with continuing concerns over future disputes with Canada and fears of another British invasion like the one that crippled the United States at the River Raisin in 1813, construction of a massive fort at Springwells finally began. Christened Fort Wayne after General “Mad” Anthony Wayne, the star-shaped fort was built on the strategic flat sandy bluff overlooking the north bank of the river adjacent to the springs, largely displacing the remaining Woodland burial mounds.

PLAN YOUR VISIT Location: Historic Fort Wayne 6325 West Jefferson Avenue Detroit, MI 48209, Phone: 734-324-7295 Hours: 6:00 a.m. to 10:00 p.m. Admission Fee: YES

THINGS TO DO Parking: Parking Lot available River Access: River View Only Trail Access: Onsite Walking Paths

Passport Stamp: NO

Guided Tours available by the Historic Fort Wayne Coalition. To make reservations call 313-628-0796.