The photographs below are displayed on the fence around Stonewall National Monument and they visually tell the story of the LGB rights movement.If you are at the park, the descriptions below help tell the story but these photographs and descriptions can be enjoyed by everyone, no matter where you are! For even more information, click on some of the pictures or check out the history of Stonewall.

After pouring their drinks, a bartender in Julius's Bar refuses to serve John Timmins, Dick Leitsch, Craig Rodwell, and Randy Wicker, all members of the Mattachine Society, an early American gay rights group, because they announced they were gay to protest New York’s liquor laws that prevented serving gay customers. New York, New York, April 21, 1966. Photo by Fred W. McDarrah/Getty Images

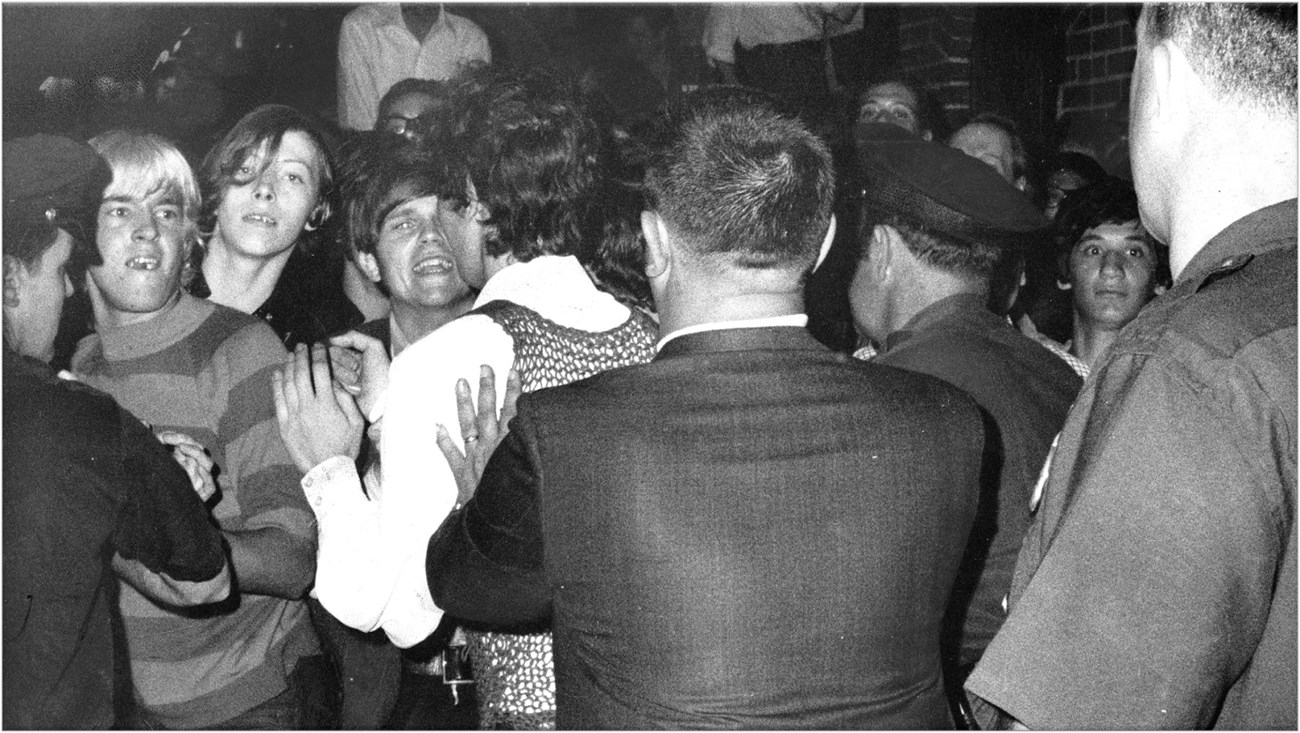

During the Stonewall Inn nightclub raid the crowd attempts to impede police arrests outside the Stonewall Inn on Christopher Street in Greenwich Village. The Stonewall Inn was frequently raided by police but this time it was different. The crowd outside began to push back against the police oppression. Many homeless LGB youth who slept in Christopher Park joined in. Photo by NY Daily News Archive via Getty Images

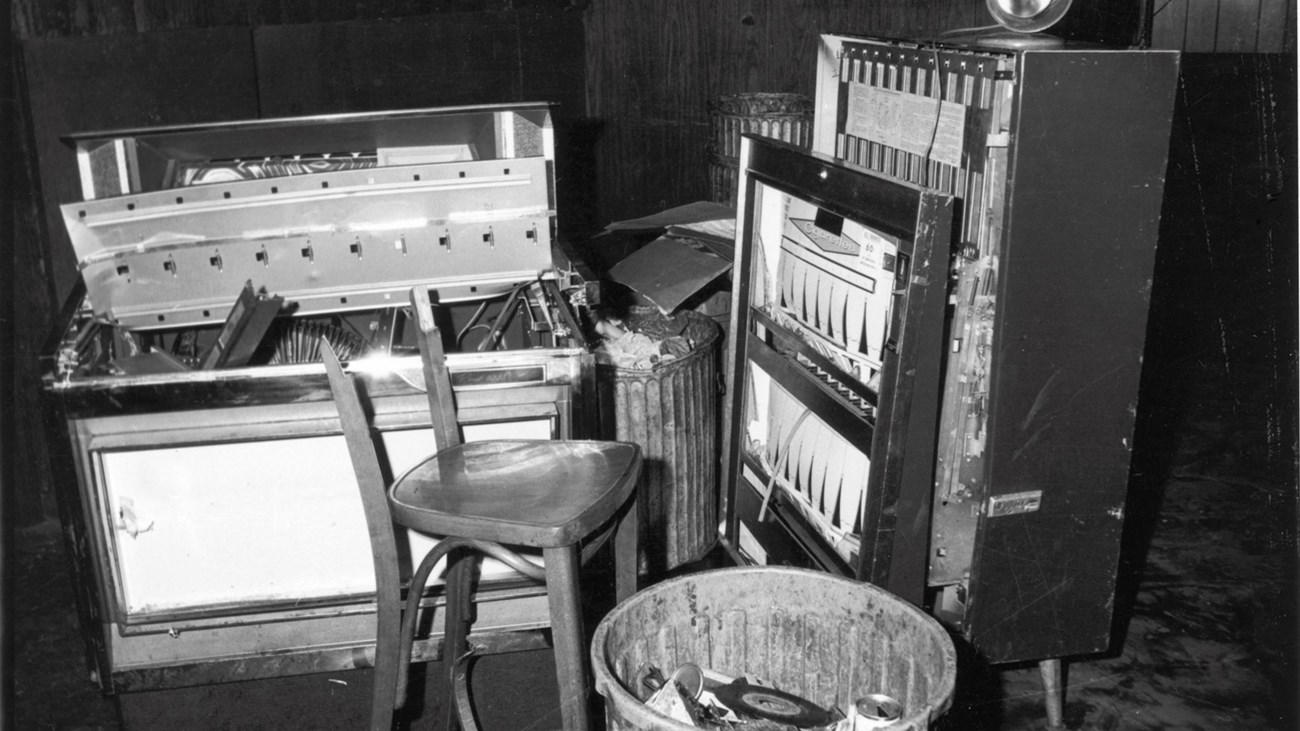

View of a damaged jukebox and cigarette machine, along with a broken chair, inside the Stonewall Inn (53 Christopher Street) after riots over the weekend of June 27, 1969. The crowd’s aggression outside of the Stonewall Inn forced the outnumbered police officers to retreat and barricade themselves inside the Stonewall Inn. Photo by Fred W. McDarrah/Getty Images

An unidentified group of young people celebrate outside the boarded-up Stonewall Inn (53 Christopher Street) after riots over the weekend of June 27, 1969. The bar and surrounding area were the site of a series of demonstrations and riots that led to the formation of the modern gay LGB rights movement in the United States. Photo by Fred W. McDarrah/Getty Images

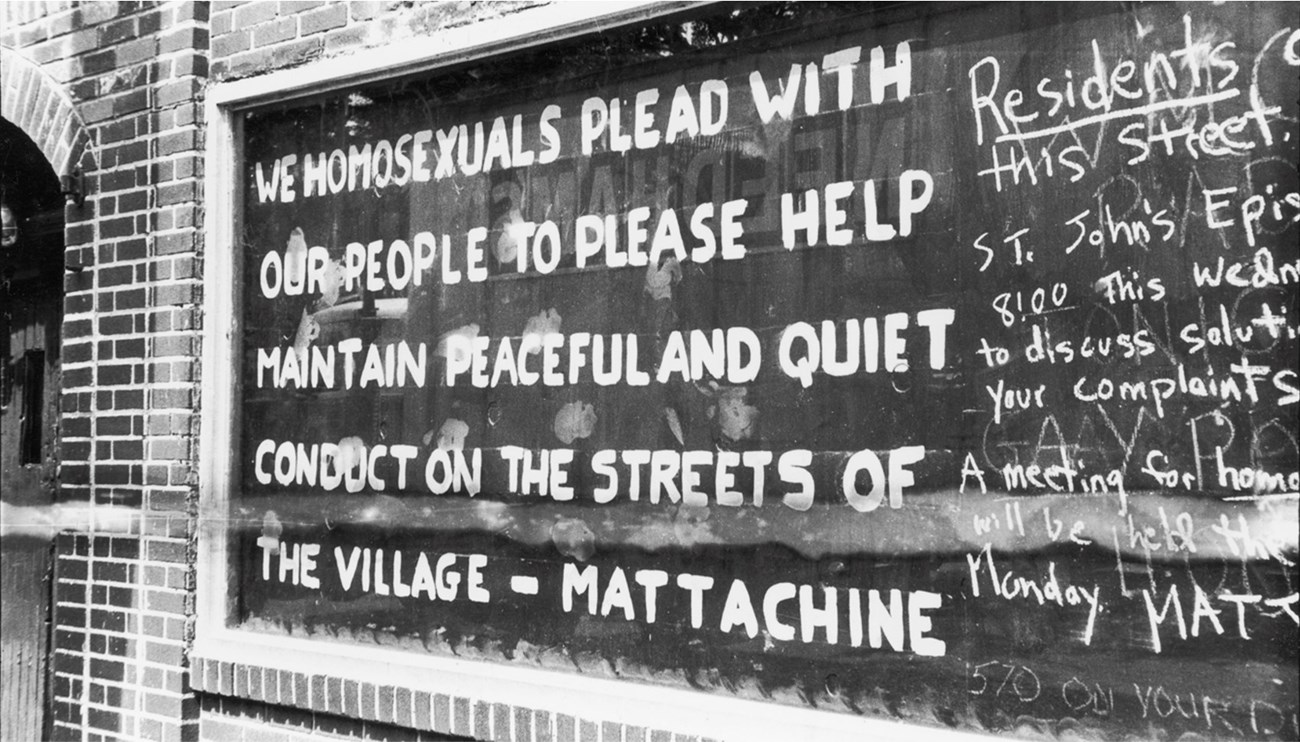

Hand-painted text on a boarded-up window of the Stonewall Inn (53 Christopher Street) after riots over the weekend of June 27, 1969. The text reads 'We homosexuals plead with our people to please help maintain peaceful and quiet conduct on the streets of the Village - Mattachine.' The Mattachine Society was an early American gay rights organization that existed in New York City before the Stonewall Uprisings. Photo by Fred W. McDarrah/Getty Images

Marsha P. Johnson hands out flyers in support of gay students at New York University while another person holds a sign reading ‘Come out of your ivory towers into the street.’ Marsha was a founding member of Gay Liberation Front (GLF) and co-founded Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR) with Sylvia Rivera. Photo by Diana Davies / New York Public Library

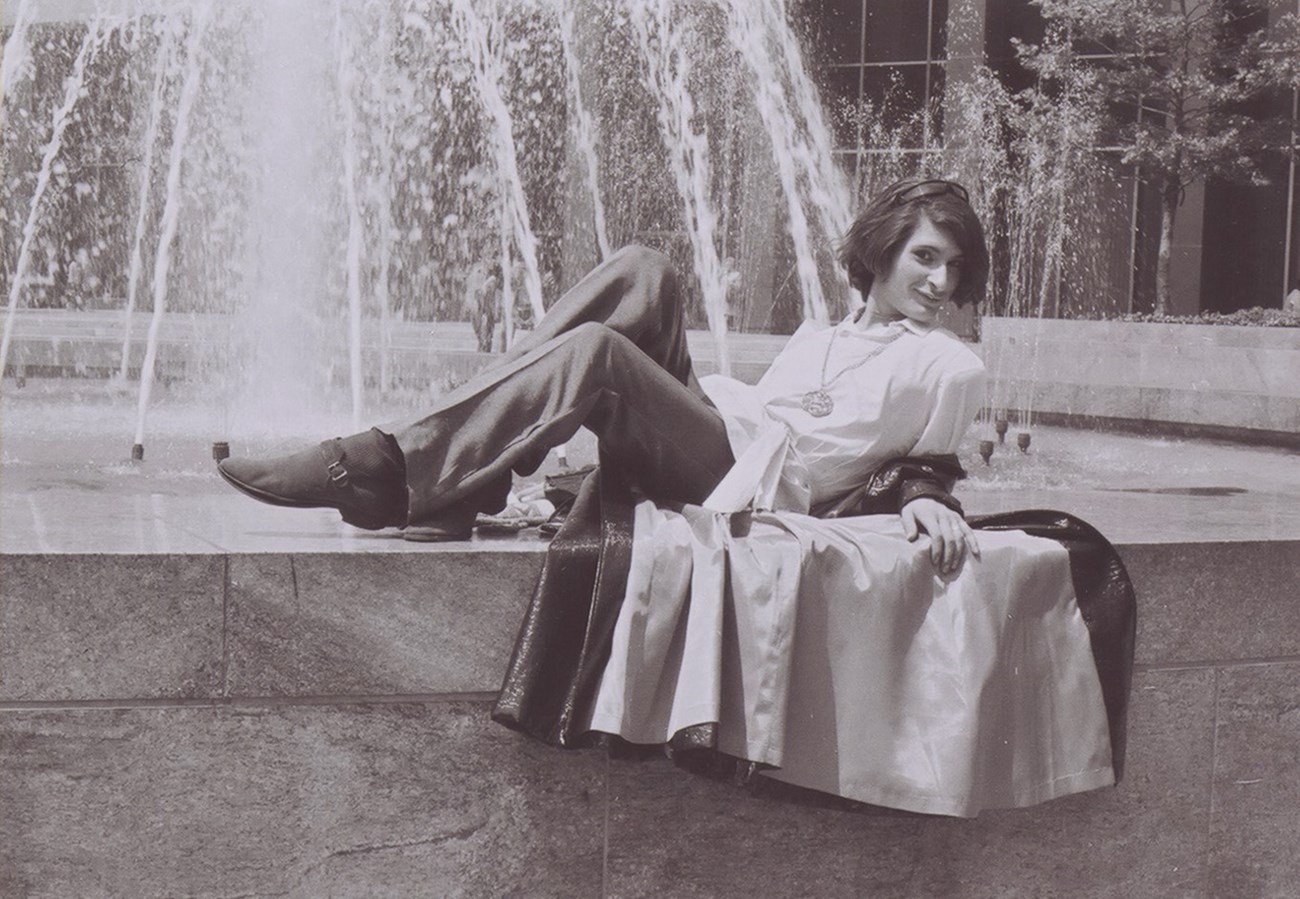

Sylvia Rivera laying back and posing on the edge of a water fountain. At a young age Sylvia began fighting for gay and rights while also helping homeless young drag queens, like herself, gay youth, and trans people. She was a co-founded of Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR) with Marsha P. Johnson. Photo by Kay Tobin / New York Public Library

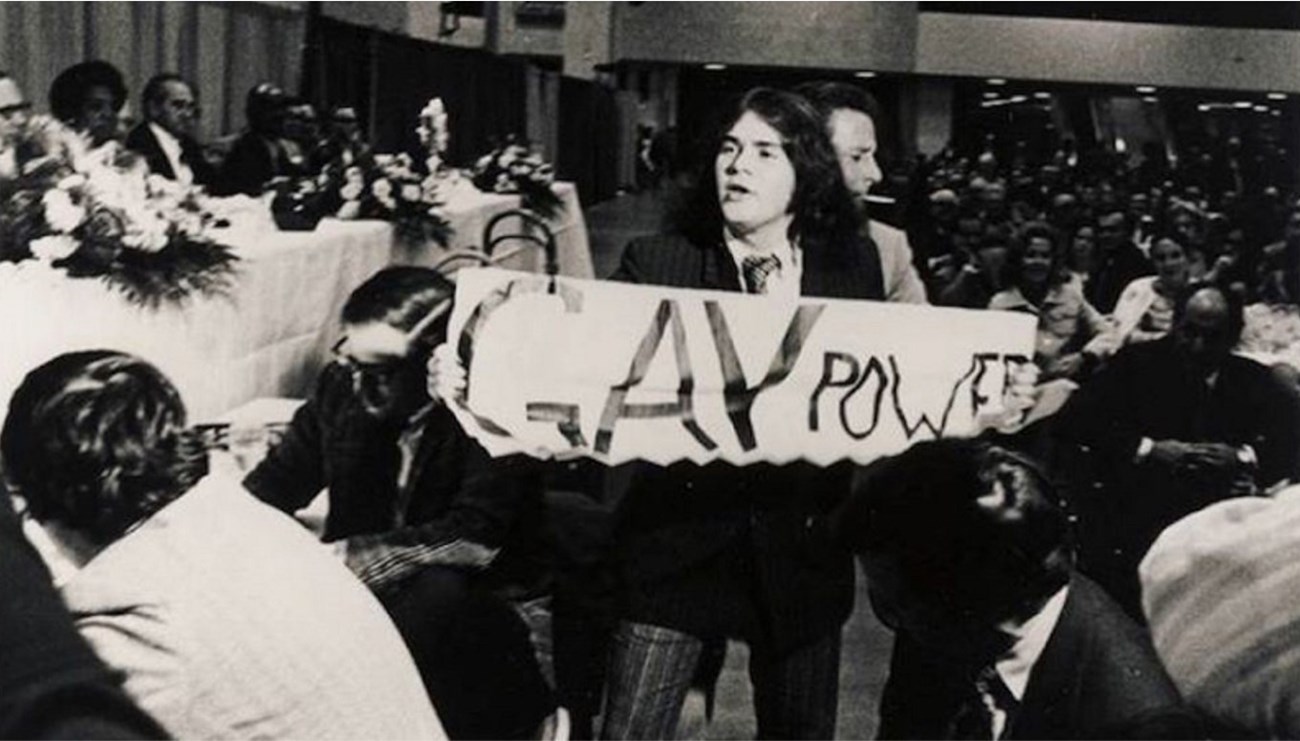

Mark Segal, founder of a radical gay activism group known as Gay Raiders, holds a sign that reads “GAY POWER” while crashing a Nixon Fundraiser to gain attention and to increase the visibility of gay people. This sort of public disruption was common for Segal who also crashed a CBS primetime news show that was watched by 60 million people in 1973 with a sign that read “Gays protest CBS prejudice.” Mark Segal / LGB History Project

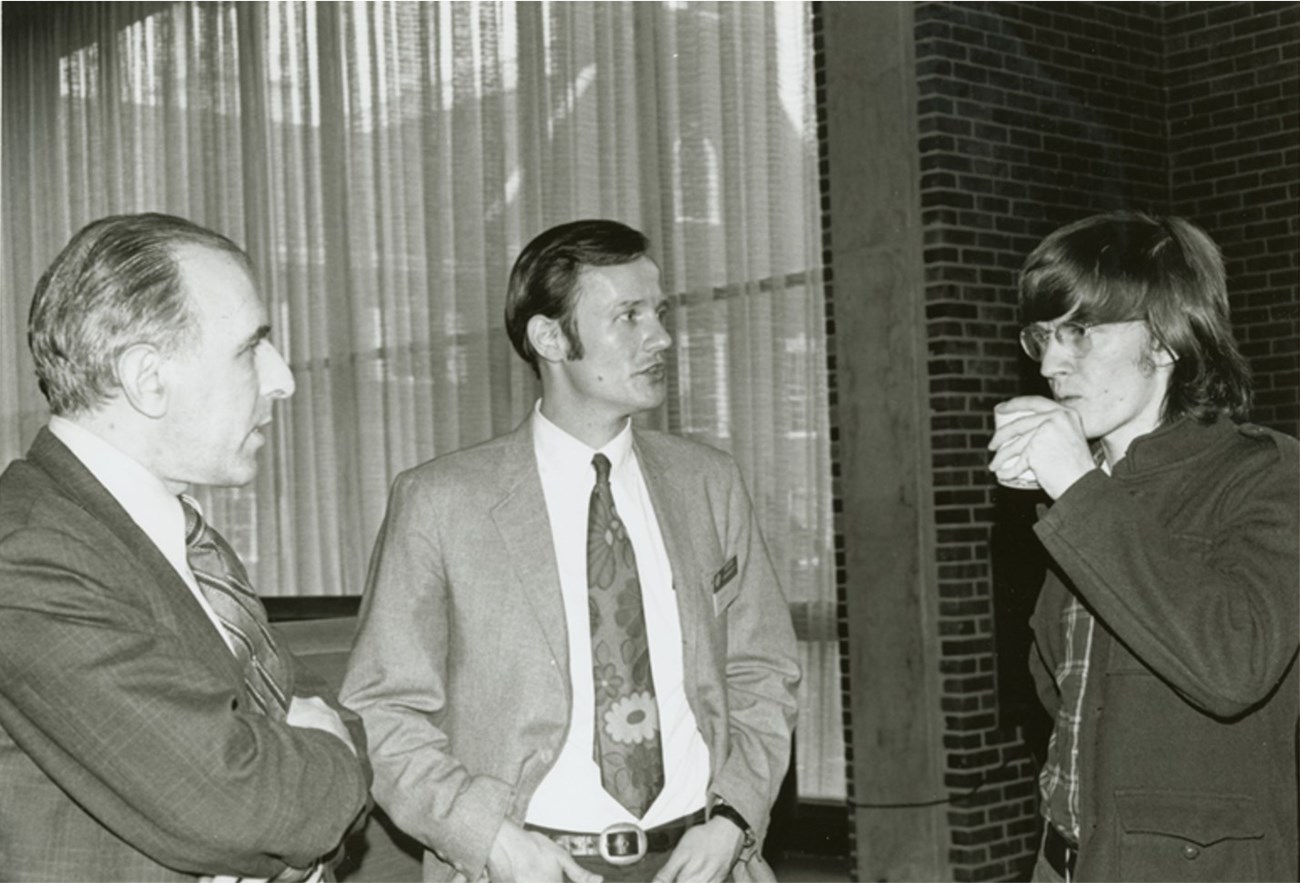

Frank Kameny, Randy Wicker, and Jim Owles attended the Rutgers Student Homophile League (SHL) sponsored Gay Liberation Conference that took place on the ground floor of the Rutgers Student Center. The SLH was the second known gay student campus organization to be formed. They were assisted by the first student organization at Columbia University, which had been organized before the Stonewall Uprising. Photo by Kay Tobin / New York Public Library

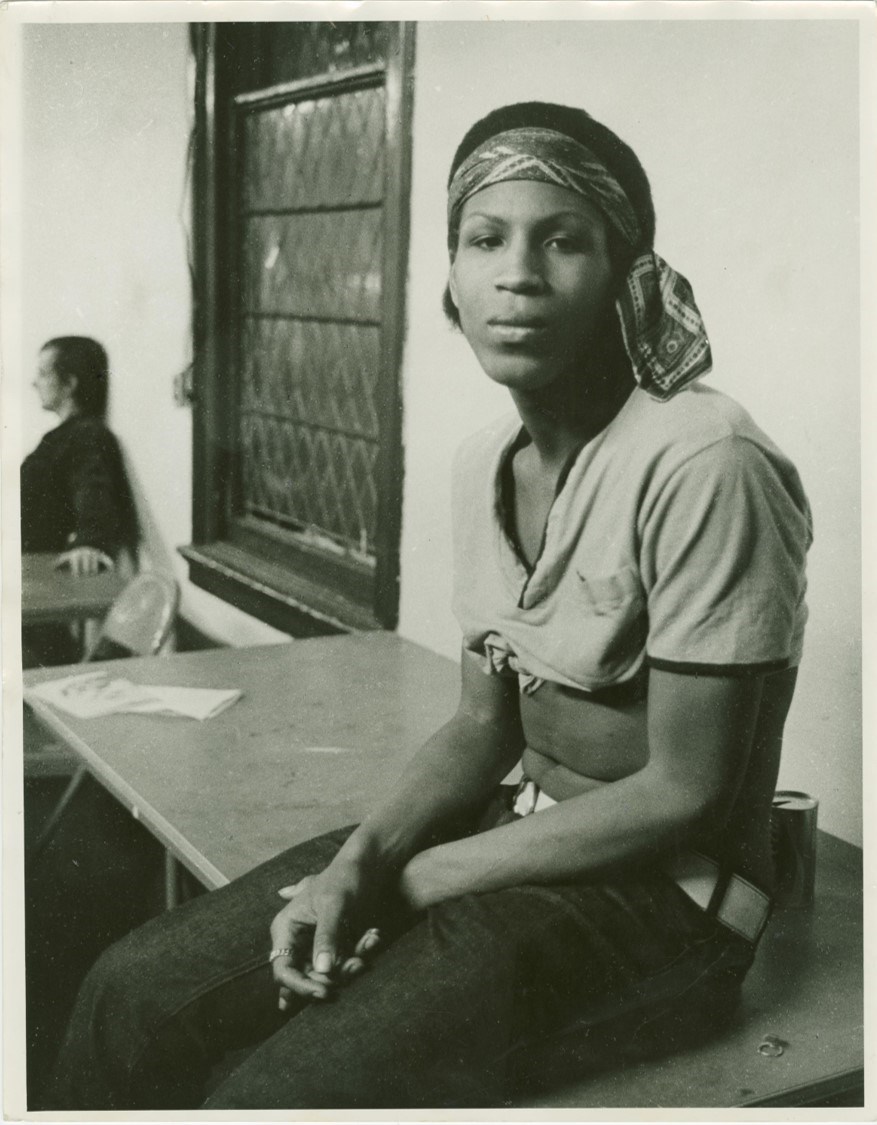

Zazu Nova, a black woman, sits on top of a table at a Gay Liberation Front meeting in 1970. Zazu was identified by many eyewitnesses as the person who may have thrown the legendary “first brick” at the Stonewall Uprising on June 28, 1969. She was a sex worker on the streets of Greenwich Village and went by “Queen of Sex.” She also was a founding member of New York Gay Youth organization to help support the gay youth of New York. Photo by Diana Davies / New York Public Library

The Gay Liberation Front (GLF) marches on times square with a banner reading ‘Gay Liberation Front.’ The GLF was a more radical gay rights activism group that seceded from the Mattachine Society. They openly marched on Times Square shortly after the Stonewall Uprising. Photo by Diana Davies / New York Public Library

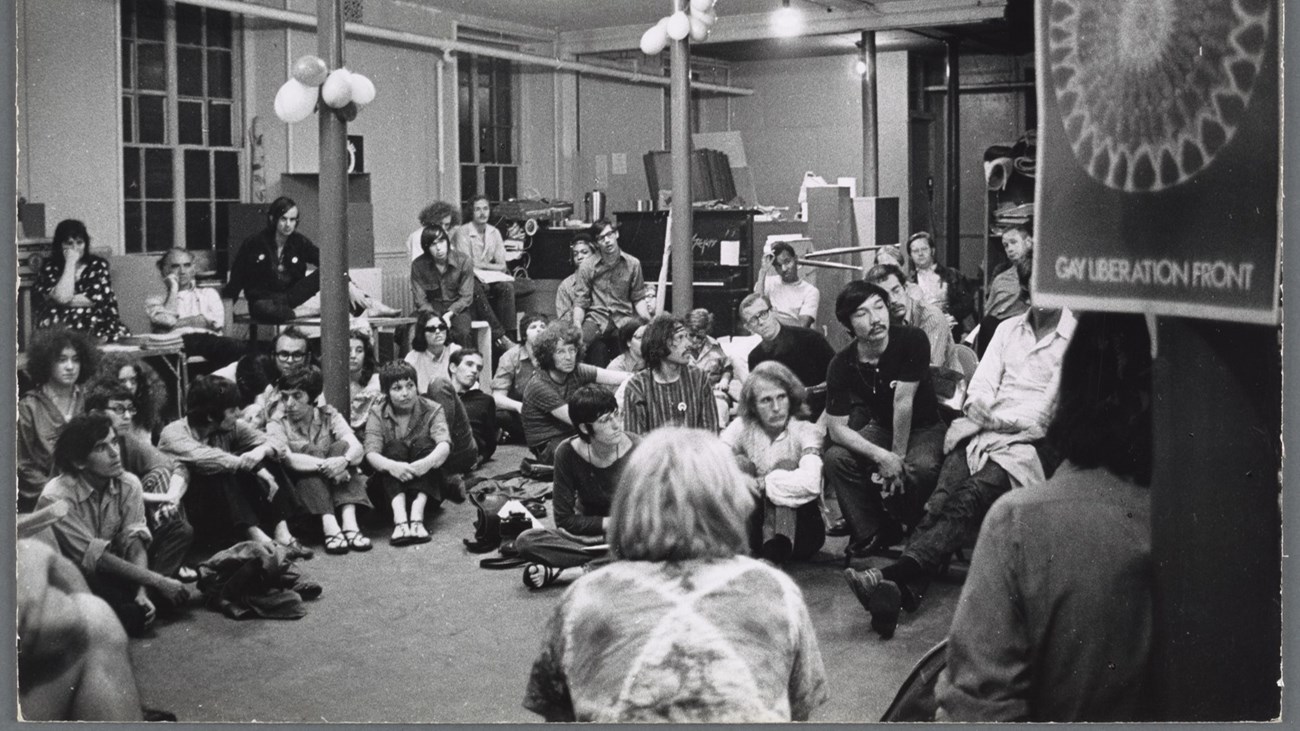

Many people sitting in chairs and on the floor with a Gay Liberation Front (GLF) sign in the foreground. GLF published their own newspaper, Come Out!, and became a springboard for many new semi-autonomous gay and lesbian groups that helped move the political movement for gay rights forward. Photo by Diana Davies / New York Public Library

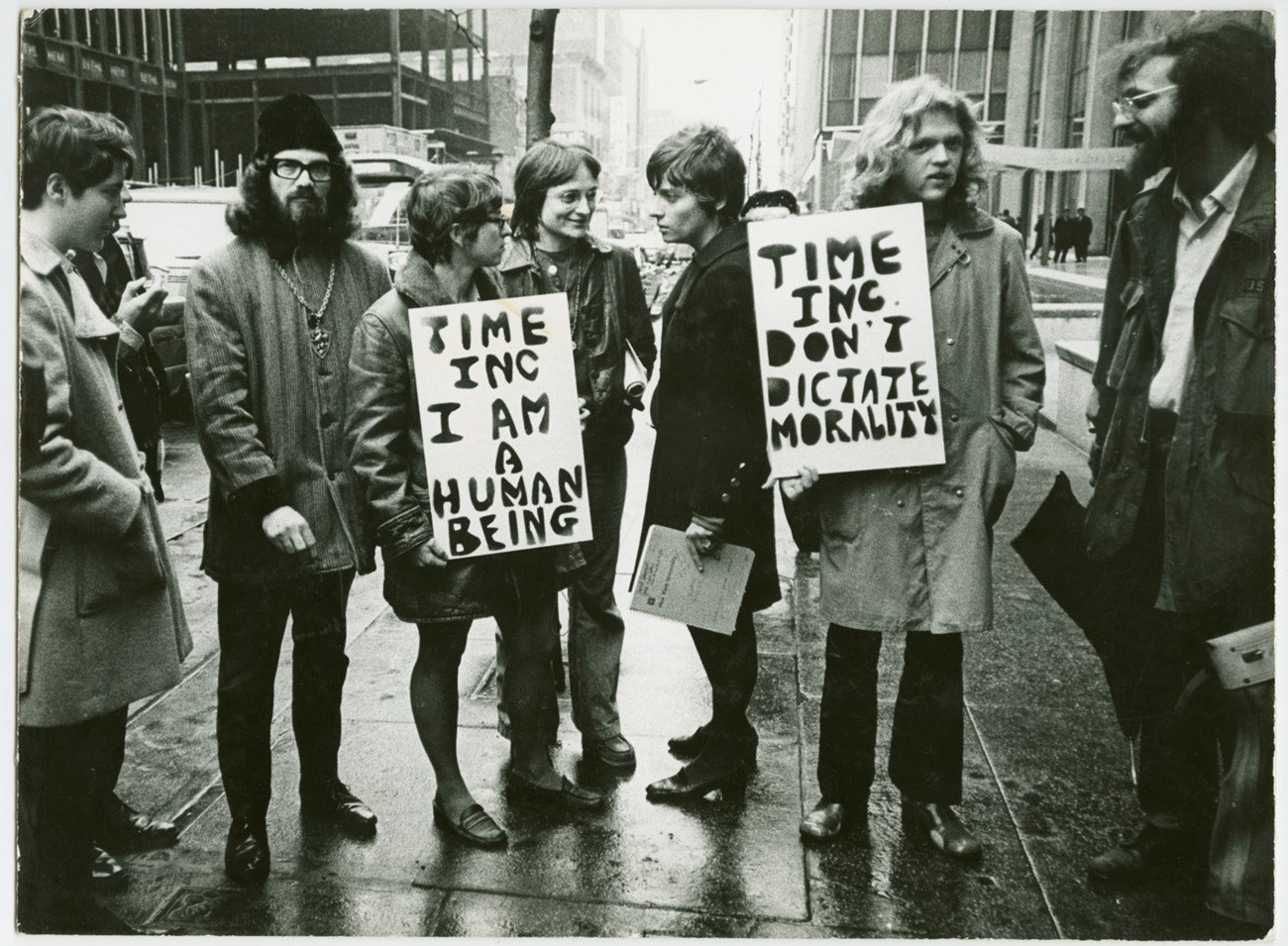

People standing on the sidewalk holding signs that read “Time Inc. I am a human being” and “Time Inc. don’t dictate morality.” While Gay Liberation Front (GLF) fought for gay rights, they also criticized the common notion of marriage, between a man and a woman, and the traditional notion of family. They fought against the idea that gay people were classified as morally and medically ‘defective.’ Photo by Diana Davies / New York Public Library

Gay Liberation Front (GFL) members Judy Cartisano and Stephanie Myers holding a sign that reads ‘Sappho was a right-on woman” at a gay pride demonstration. Sappho, the poetess of Ancient Greece lived on the island of Lesbo, where the word ‘lesbian’ comes from, about 600 BCE and wrote about the love of women for women. GLF member Sue Schneider wrote a poem called “Sappho was a right-on woman.” Photo by Diana Davies / New York Public Library

Three lesbians wearing ‘Lavender Menace’ shirts. The National Organization of Women President referred to lesbians as the “lavender menace,” for fear that lesbians would hinder the reputation of the women’s rights movement. To protest their exclusion, a group of lesbians wore ‘Lavender Menace' shirts to the NOW's Second Congress to Unite Women. This lead to NOW's support of lesbians in 1971. Photo by Diana Davies / New York Public Library

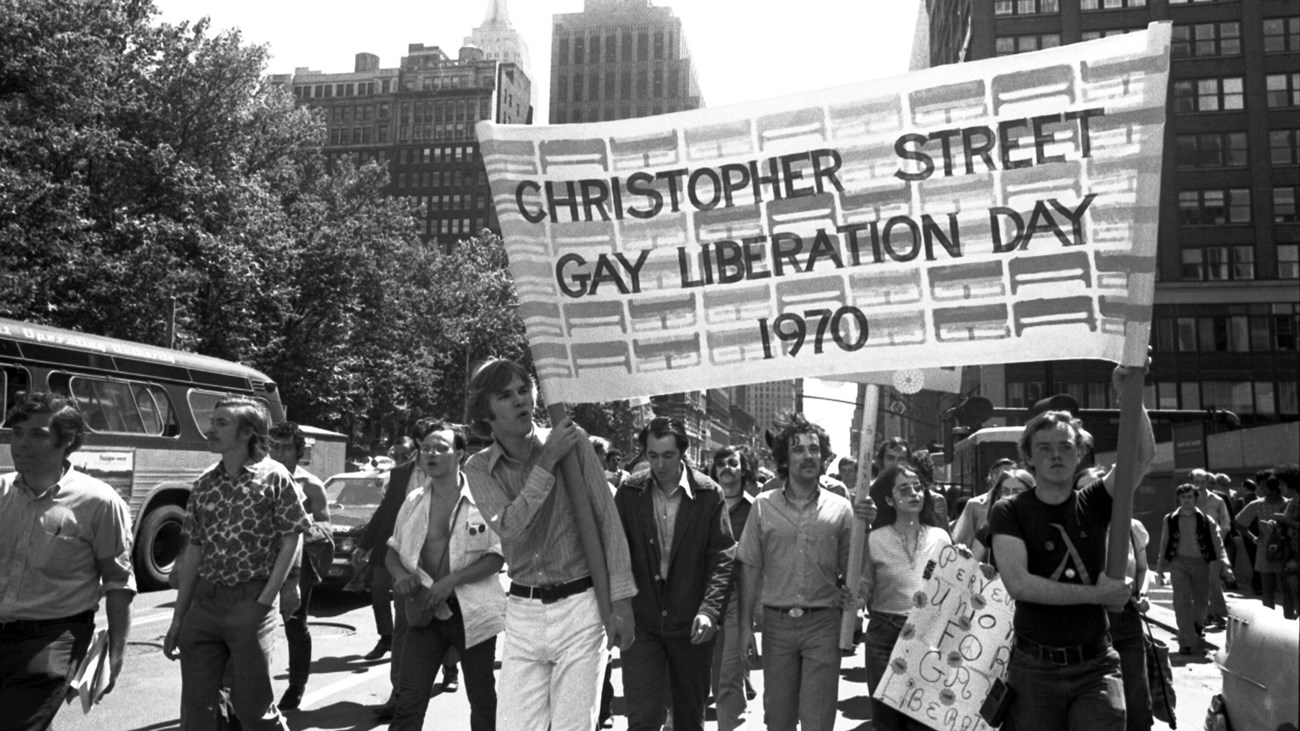

Men holding ‘Christopher Street Gay Liberation Day 1970’ banner while walking down the middle of the street in NYC. To mark the anniversary of the Stonewall Uprising the previous year, gay activists organized a march from Washington Place to Central Park on June 28, 1970. They were not sure if they would even reach Central Park but as more people joined the march it received a lot of media coverage and attention. Photo by Diana Davies / new York Public Library

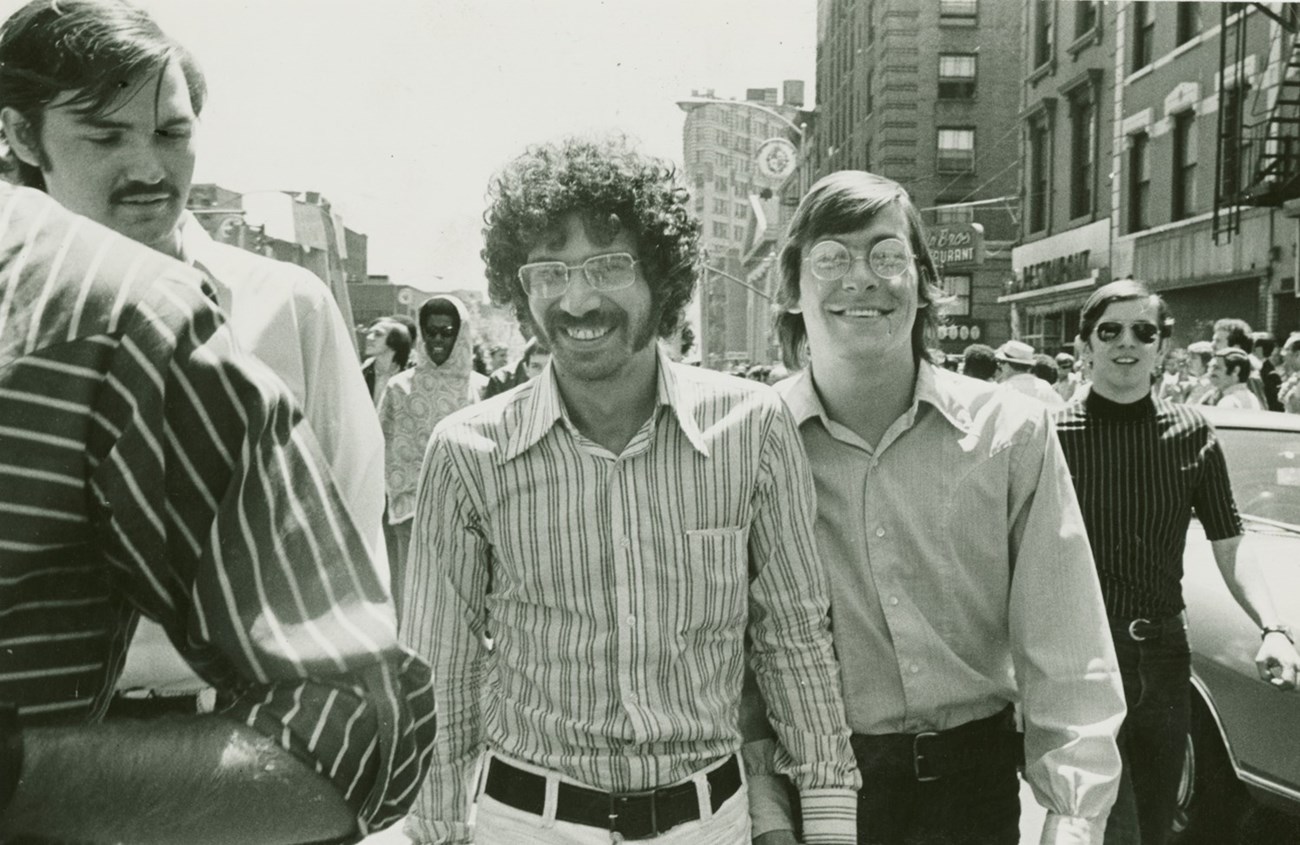

Two men holding hands and smiling while marching in the Christopher Street Liberation Day march on June 28, 1970. Many people that participated in this first march had worried about police intervention and other possible threats for openly fighting for gay rights. It took courage for LGB people to engage in public displays of affection for fear of being arrested or beat. The march was successful and helped raise awareness and visibility for gay rights. Photo by Diana Davies / New York Public Library

Thousands of people sitting in the park with signs read “lesbians unite,” “gay pride,” and “New York Mattachine.” The Christopher Street Liberation Day march ended with the “Be-In” event at Sheep Meadow in Central Park. The march and “Be-In” attracted thousands of people and successfully unified many gay rights activist groups and supporters to all embrace the one-year anniversary of the Stonewall Uprising, making it's place in history solidified. Photo by Diana Davies / New York Public Library

Stonewall National Monument (the monument) is a 7.7-acre site in the Greenwich Village neighborhood of New York City established by presidential proclamation in 2016. The monument encompasses both public and private property, including the privately owned Stonewall Inn, portions of the New York City street network, and 0.12-acre Christopher Park, which was donated to the federal government by the City of New York. Department of the Interior

(Left to Right) Artist Miss Simone, NPS Superintendent Shirley McKinney, and LGB activist Steven Love Menendez raise the Progress flag at Christopher Park. The ceremony also included a land acknowledgement from Janis Stacey (a member of the Two Spirit community), a performance by Broadway star Lillias White, and speeches from LGB activists Ann Northrop and Michael Petrelis. Photo by Donna Aceto

Viewed from Christopher Park’s central location, this historic landscape—the park itself, the Stonewall Inn, the streets and sidewalks of the surrounding neighborhood—reveals the story of the Stonewall uprising, a watershed moment for LGB rights and a transformative event in the nation’s civil rights movement. It was not the first time members of the LGB community organized in their own interest. Yet, the movement to commemorate Stonewall on the first anniversary of the event inspired the largest and most successful collective protest for LGB rights the nation had ever seen. As one of the only public open spaces serving Greenwich Village west of 6th Avenue, Christopher Park has long been central to the life of the neighborhood and to its identity as an LGB-friendly community. The park was created in 1837 after a large fire in 1835 devastated an overcrowded tenement on the site. By the 1960s, Christopher Park was a destination for LGB youth, many of whom had run away from or been kicked out of their homes. Christopher Park served as a gathering place, refuge, and platform to voice demands for LGB civil rights. Christopher Park continues to be an important place for the LGB community to assemble for marches and parades, including the annual NYC Pride; expressions of grief and anger; and celebrations of victory and joy. |

Last updated: February 13, 2025