History of Paleontology in the National Park Service—Santucci, V. L. (page 3 of 9)

NPS painting by Sidney E. King.

Introduction

This period spans from the earliest sustained exploration of the New World by Europeans (1492) through the end of the 18th century. This portion of American history encompasses the exploration, colonialization, conflict, independence, birth and early organization of a new nation. This period extends up to the eve of the presidency of Thomas Jefferson and significant fossil discoveries on lands that would later be managed by the National Park Service.

The first published fossils from the New World

Long before the United States was an independent country and even longer before there was a US National Park Service, a remarkable fossil story was unfolding during the colonial period. During the late 17th century, fossils were collected from the bluffs and cliffs along the James and York rivers; lands which would later be included within Colonial National Historical Park. The fossils were shipped back to Europe for sale to collectors of natural history objects and some were eventually curated into European museums and other institutions. Information about this early fossil collecting was discovered while conducting research to gather baseline paleontological resource data for the national parks in the Eastern Seaboard states and the Atlantic Coastal Plain. These fossils hold an important place in the history of American paleontology.

The fossil-rich strata of the Virginia Coastal Plain and the shell beds along the cliffs of the James River, not far from colonial Jamestown, were well known to the local English settlers. These fossil beds (Pliocene Yorktown Formation) were a source of lime for producing mortar used in construction and are referenced in documents prepared by William Strachey, the first secretary of Jamestown, and by early naturalists John Banister and John Clayton (Ray 1983). Fossils and other natural history specimens were often collected by cartographers and seamen as objects to bring back to Europe to sell to naturalists or private collectors (Kenworthy and Santucci 2003).

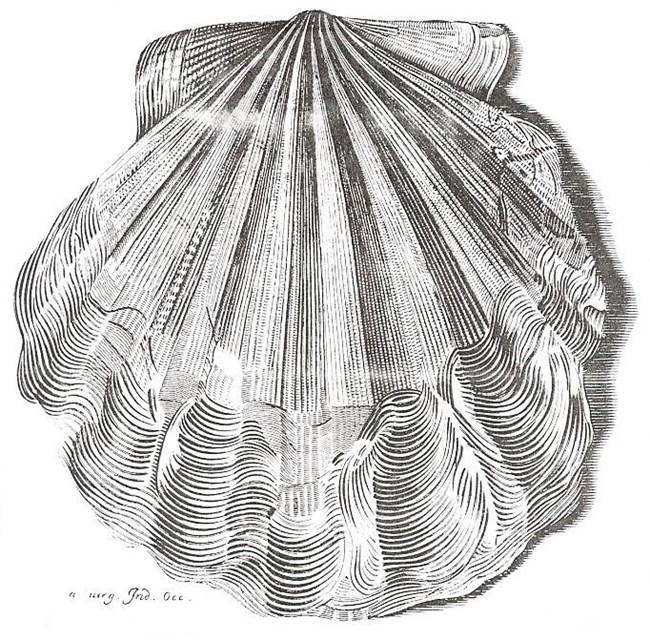

The fossil mollusks from the Virginia coastline and James River came to the attention of English naturalist and physician Martin Lister. In 1687, Lister published an illustration of one of the Yorktown Formation bivalve fossils (Pecten) in Historiae Conchyliorum (Lister 1687; Ward and Blackwelder 1975; Ray 1987; Tweet et al. 2014). The significance of Lister’s 1687 publication is likely more historic than scientific, as this work represents not only the first figured fossil specimen from a national park, but also the first figured fossil from America, the New World, and the Western Hemisphere!

During the aftermath of the American Revolution, the fossils from along the James River and the Yorktown Battlefield area (later to become part of Colonial National Historical Park) continued to draw the attention of scientifically minded soldiers on both sides of the conflict. American General Benjamin Lincoln, who served at the siege of Yorktown, reported the presence of fossilized cockles (bivalves), clams, and other shells in several different layers exposed in the steep banks (Lincoln 1783). The German naturalist Johann David Schöpf, who served as a physician for the British Hessian troops, visited Yorktown in 1783 and noted the shell beds and probable fragments of whale bones (Ray 1983).

An additional note of interest related to the history of paleontology is tied to Colonial National Historical Park. Thomas Say described and published on a number of invertebrate fossils from the Yorktown Formation near Colonial National Historical Park (Say 1822, 1824). In 1824 Thomas Say formally described, named and published on Lister’s fossil Pecten originally published in 1687, and assigned the genus and species Pecten jeffersonius in recognition of President Thomas Jefferson’s great interest in fossils (Say 1824). The genus was renamed Chesapecten approximately 150 years later (Ward and Blackwelder 1975), and in 1993 the Commonwealth of Virginia designated Chesapecten jeffersonius as the state fossil.

Mastodon tooth mystery from Ben Franklin’s home in Philadelphia

A single fossil specimen in the museum collections of Independence National Historical Park, Pennsylvania, represents a little-known history about our founding fathers and their interests in fossils. Ben Franklin, Thomas Jefferson and some of their contemporaries found fossilized remains of ancient animals to be fascinating natural history curiosities during a period of intellectual enlightenment. In 1767, Benjamin Franklin received some fossilized mastodon bones and teeth collected by a western lands speculator and Indian Agent named George Groghan.

In 1953, a mastodon molar was discovered in the basement of Franklin’s home on Market Street in Philadelphia. The home was built by Franklin in 1786 and today is part of the area referred to as Franklin Court within Independence National Historical Park. Franklin lived in Philadelphia while serving in the Continental Congress and the Constitutional Convention and used the home as a rental property. The mastodon tooth is the only fossil within the large museum collection for Independence National Historical Park.

1800–1865

Antebellum through Civil War

Related Links

-

Colonial National Historical Park (COLO), Virginia—[COLO Geodiversity Atlas] [COLO Park Home] [COLO npshistory.com]

-

Independence National Historical Park (INDE), Pennsylvania—[INDE Geodiversity Atlas] [INDE Park Home] [INDE npshistory.com]

Last updated: April 27, 2023