NPS photo archive.

Introduction

Regardless of the size of a volcanic eruption or when it occurred, volcanic activity is one of the Earth’s most awe-inspiring processes. Volcanic eruptions have always left indelible marks on all who witnessed them. Traditional knowledge of Native American tribes includes accounts of what appear to be volcanic eruptions.

By convention, prehistoric volcanic eruptions are those that occurred during the Holocene (the last 11,700 years), but prior to 1700 CE (common era). The usage of the term prehistoric doesn’t mean that these eruptions were not witnessed by people, just that they are further back in time when written records did not exist in North America.

Traditional knowledge that relates to prehistoric eruptions is part of the oral history of many Native American tribes. This knowledge even extends back to volcanic activity that occurred thousands of years in the past.

In addition to oral histories, archeological sites near some volcanoes show some of the ways people were influenced by eruptions.

Large eruptions may have impacted the lives of people in large areas covering hundreds of square miles, whereas small eruptions may have affected only people living in the volcano’s immediate vicinity.

Sunset Crater Volcano National Monument

Photo by Helga Teiwes courtesy of Desert Archaeology, Inc

The 1085 CE eruption of Sunset Crater Volcano in northern Arizona was witnessed by ancestral Puebloan people living in the area according to oral traditions that are still shared by their descendants in the Hopi and Zuni villages.

Sunset Crater eruption had significant impacts on ancestral Puebloan people living in the area as volcanic ash from the eruption covered an area of 140 square miles (400 square km) with ash deep enough (greater than 1 foot or 30 cm) to cause crop failure. Other areas with thinner ash deposits were made more fertile.

Archeological evidence found in one site near Sunset Crater Volcano indicates that people interacted with active volcanic features during the eruption. Corn imprints in pieces of volcanic rock from the eruption were found in an archeological site approximately 2.5 miles (4 km) from the Sunset Crater lava flow. These “cornrocks” likely were produced by deliberately placing corn around a hornito or spatter cone in a ritual behavior.

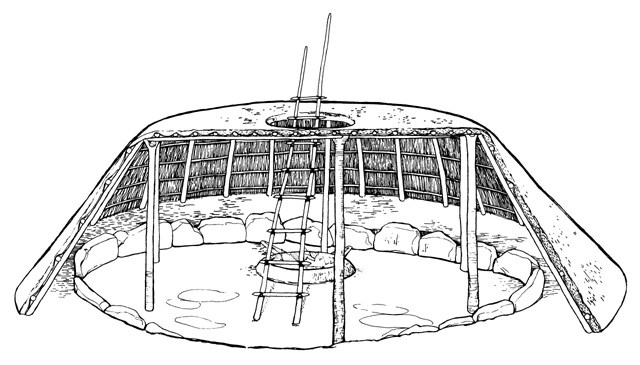

Buried under Sunset Crater’s lava and cinders are perhaps dozens of pithouses. Those excavated revealed few artifacts; even building timbers had been removed. This suggests people had ample warning of the impending eruption. The changed environment forced new adaptations, which included migration from the area.

NPS commissioned art collection.

Little Springs Lava Flow / Grand Canyon-Parashant National Monument

Photo by Helga Teiwes courtesy of Desert Archaeology, Inc.

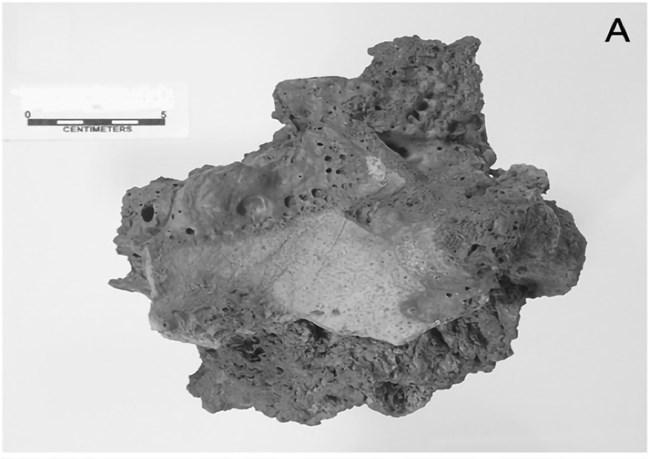

Ancestral Puebloan people apparently witnessed a Hawaiian eruption of a basaltic lava in the Uinkaret Volcanic Field in Grand Canyon-Parashant National Monument about 1,000 years ago. Several rocks that consist of welded cinders that also have pieces of broken of pottery found in them were found in an archeological site near the Little Springs lava flow. Similar to the ritual behavior that created “cornrocks” near Sunset Crater Volcano, it appears that people may have placed pots or pot sherds near a hornito or spatter cone during the eruption.

Craters of the Moon National Monument

Members of the Shoshone and Bannock tribes who inhabited the lava fields in Craters of the Moon National Monument likely witnessed eruptions. The Serpent Legend appears to reflect volcanic processes as it describes rocks beginning to melt, fire coming from cracks, and liquid rock flowing down.

(Ella Clark, Indian Legends of the Northern Rockies, p. 193-194)

Long, long ago, a huge serpent, miles and miles in length, lay where the channel of the Snake River is now. Though the serpent was never known to harm anyone, people were terrified by it. One spring, after it had lain asleep all winter, it left its bed and went to a large mountain in what is now the Craters of the Moon. There it coiled its immense body around the mountain and sunned itself. After several days, thunder and lightning passed over the mountain and aroused the wrath of the serpent. A second time flashes of lightning played on the mountain, and this time the lightning struck nearby. Angered, the serpent began to tighten its coils around the mountain. Soon the pressure caused the rocks to begin to crumble. Still the serpent tightened its coils. The pressure became so great that the stones began to melt. Fire came from the cracks. Soon liquid rock flowed down the sides of the mountain. The huge serpent, slow in its movements, could not get away from the fire. So it was killed by the heat, and its body was roasted in the hot rock. At last the fire burned itself out;the rocks cooled off;the liquid rock became solid again. Today if one visits the spot, he will see ashes and charred bones where the mountain used to be. If he will look closely at the solidified rock, he will see the ribs and bones of the huge serpent, charred and lifeless.

Bering Land Bridge National Preserve

Jessica Larsen AVO/UAF-GI.

The Lost Jim lava flow is described in the oral history of the Inupiat-speaking Kaweruk people native to central Seward Peninsula (Oquilluk and Bland 1981; Hopkins 1988). The following is a passage from chapter two of the book “People of Kauwerak: Legends of the Northern Eskimo,” by Oquilluk and Bland (1981). This passage recounts a story about Ekeuhnick, a legendary leader of the Inupiat people, that seems to be describing the eruption of the Lost Jim lava flow.

On the third day after the people moved, Ekeuhnick went to the spring again before the sun went down. He rested and watched the animals drinking at the springs. He enjoyed seeing them. Later, he started back towards the place his people lived.

Suddenly, he could feel the ground shaking under him. Three times the shaking of the ground passed under his feet. Then he heard a roaring and a loud rumble. He looked back and saw that the great mountain was blowing up. The noise got worse and worse and he began to get scared. A big black smoke came out from the top of the mountain. A terrible red tongue of fire came out of the top of the smoke. At the same time, red hot coals came out from the top and rolled down the side of the mountain towards the old place of his people. Ekeuhnick began to hear all kinds of confusion. He looked around and saw many kinds of birds and animals running and flying toward him.

The animals were all running away together, big and small, and the birds in the air. As the animals passed by, Ekeuhnick jumped up and rode on the back of a scared stampeding bear. He held it tight by the neck so they could keep up with the other animals. There was so much noise from the birds in the air and the animals he could not hear the noise of the mountain or anything else.

Together Ekeuhnick, the birds, and the animals fled fast away from the mountain. The birds and animals, every living thing was running and flying at the same time, all in the same direction.

Ekeuhnick’s people, far away and safe from the mountain, heard an awful noise like a terrible bellow coming from behind them. Everyone turned and looked. A great spear of fire was coming from the mountain from the top. Everything was blazing all around it. There was a red-orange color rolling all the way down from the top of the mountain to the bottom. The people were amazed and very frightened. Now those people began to see the things Ekeuhnick had told them about. It was happening, and his words were true.

All the birds and animals around began running and flying across the plain. They made so much noise that the people got more scared. It seemed everything on the mountainside was burning and the fire was coming down to the plain below the mountain. The people could see birds and animals running away before the fire and coming towards them.

The animals were traveling so fast that soon they came near to where the people were standing. Then Ekeuhnick jumped off the big bear. He joined his people. He was relieved when he looked back at the mountain so far away from them. His people were glad to see Ekeuhnick. They thought he was burned up by the mountain fire. Now that his words were coming true, they would talk together more about the things Aungayoukuksuk had foretold.

Two days after the eruption, Ekeuhnick woke up early and went to where he used to meet with Aungayoukuksuk. It was cold and the wind was blowing. The weather turned good when he came round to the place of the old man. He saw Aungayoukuksuk still sitting there in the same place. He was glad to meet Ekeuhnick again.

“Now,” said the old prophet, “you are to become my servant so you may serve and lead your people. You must go beyond this mountain on a long journey.”

Ekeuhnick sat down face to face with Aungayoukuksuk. He looked around the place. He saw a great change. There was only black rock, like water frozen, everywhere. There was no kind of green living things around and not even a bird or animal anywhere. He saw that the water was still running from the springs same as ever. The place seemed deserted, it was so quiet.

[Lanik A and Others. 2019. Bering Land Bridge National Preserve: Geologic resources inventory report. Natural Resource Report. NPS/NRSS/GRD/NRR—2019/2024. National Park Service. Fort Collins, Colorado]

El Malpais National Monument

Traditional knowledge of the El Malpais lava flows, of which the most recent erupted 3,900 years ago, are reflected in Navajo (Diné), Acoma, and Laguna stories. For example, Monsterway, a Diné ceremony, says that the El Malpais lava flows are the hardened blood of an enemy that had been killed by the Hero Twins near Mount Taylor.

Oral tradition of the Acoma people is that lava flows destroyed the corn fields of their ancestors.

Mount Mazama / Crater Lake National Park

Oral traditions of the Klamath tribes and Umpqua people indicate that people witnessed the eruption of Mount Mazama 7,700 years ago. Artifacts have also been found underneath the Mazama ash layer.

Hawai’i Volcanoes National Park

Hawaiian traditional knowledge is reflected in Moʻolelo, which are the stories, myths, and legends, that are part of the cultural fabric of Hawaiʻi. The characteristics of the volcano deity Pele reveal an understanding that volcanic processes are both constructive and destructive. Pele destroys landscapes and also creates new land. According to custom, she lives in Halemaʻumaʻu crater at the summit of Kīlauea.

Featured Parks

-

Crater Lake National Park (CRLA), Oregon—[CRLA Geodiversity Atlas] [CRLA Park Home] [CRLA npshistory.com]

-

Craters of the Moon National Monument (CRMO), Idaho—[CRMO Geodiversity Atlas] [CRMO Park Home] [CRMO npshistory.com]

-

El Malpais National Monument (ELMA), New Mexico—[ELMA Geodiversity Atlas] [ELMA Park Home] [ELMA npshistory.com]

-

Grand Canyon-Parashant National Monument (PARA), Arizona—[PARA Geodiversity Atlas] [PARA Park Home] [PARA npshistory.com]

-

Hawai’i Volcanoes National Park (HAVO), Hawai’i—[HAVO Geodiversity Atlas] [HAVO Park Home] [HAVO npshistory.com]

-

Lassen Volcanic National Park (LAVO), California—[LAVO Geodiversity Atlas] [LAVO Park Home] [LAVO npshistory.com]

-

Sunset Crater Volcano National Monument (SUCR), Arizona—[SUCR Geodiversity Atlas] [SUCR Park Home] [SUCR npshistory.com]

Last updated: April 18, 2023