Last updated: November 30, 2021

Article

Chestnut Oak / Mountain Laurel Forest in Rock Creek Park

Sam Sheline, courtesy of NatureServe / Creative Commons BY

How to Recognize It

This natural community at Rock Creek Park is easy to spot because of the abundance of chestnut oak and near absence of American beech. The understory can be an almost continuous layer of mountain laurel, an evergreen shrub in the heath family. You’ll find the Chestnut Oak / Mountain Laurel Forest on or near ridgetops and hilltops where the soil is dry, acidic, and infertile. In Rock Creek Park, this natural community grows on coarse soil, over ancient river deposits of cobbles, gravels and sand that cap some ridges in the park. Listen to a podcast about this natural community.

-

Natural Community: Chestnut Oak / Mountain Laurel Forest

Rugged survivalists on a hilltop.

- Credit / Author:

- Abby Cox

Identifying This Natural Community

-

Old-age chestnut oak in the forest canopy

-

Near-absence of other oaks and American beech

-

Chestnut oak seedlings on the forest floor

-

Twisted, dark stems of tall mountain laurel shrub in the understory (look for their pink blooms in early summer)

-

Acorns over an inch long

-

Cobbles (rounded, potato-sized stones) at the base of large trees where erosion and frost action have exposed them

-

Location: a hilltop or upper slope

If so, welcome to Rock Creek Park’s Chestnut Oak / Mountain Laurel Forest!

Not sure? Check out Tips to Distinguish (below).

Seasonal Highlights

Spring Highlights

- Pink to whitish blooms of pink azalea, hillside blueberry, mountain laurel (late spring)

- White blooms of flowering dogwood

- Nesting birds vocally setting up territories and attracting mates

- Migratory birds arriving or heading north (look for them in early morning on the hilltops where the sun’s rays hit first, warming them and activating their insect prey)

- White-chested, solitary red fox might be seen hunting rodents or insects. A male fox will hunt to feed his mate before and after she gives birth in spring.

Summer Highlights

- Pink blooms of mountain laurel (early summer)

- Pinkish to red blooms of black huckleberry

- White blooms of striped prince's-pine (usually in two or threes), twin blooms of partridgeberry (early summer)

- Dark berries of hillside blueberry and black huckleberry

- Low-to-the-ground chestnut oak seedlings with their distinctively scalloped leaves

- Female red fox might be seen, her coat looking scruffy from pulling out fur for spring nests. Pups may accompany parents outside the den. Dens are sometimes dug in the soil that clings to the roots of large fallen trees.

Autumn Highlights

- White wood-aster in bloom

- Brilliant orange and red leaves of blackgum

- One-inch long acorns of the chestnut oak

- Yellow blooms of American witch-hazel

- Red berries of partridgeberry and flowering dogwood

- Migratory birds passing through on their way south

- Solitary foxes may be seen sunning themselves, foraging, or hunting. Red fox pups leave their parents in the fall.

Winter Highlights

- Evergreen leaves and dark contorted stems of mountain laurel

- Dark and deeply furrowed bark of chestnut oak

- Green bare twigs of hillside blueberry

- Open vistas that allow you to see the shape of the land, including rock outcrops

- Perhaps a solitary fox hunting or foraging for acorns - look for tracks in snow

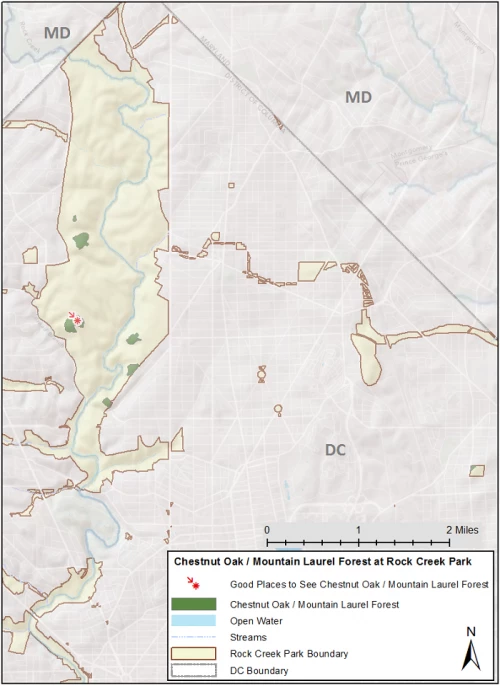

Where to See It

One of the best examples in the park of the Chestnut Oak / Mountain Laurel Forest can be found on the hilltop beside Picnic Area 16 on Glover Road. This stand is also visible from the White Horse Trail that cuts across the same forested knoll. A cross-sectional view of the soil profile there would reveal a thin layer of duff (decaying leaves and twigs) overlying a thick layer of sandy soil full of smooth stones such as you might find in a riverbed.

Area Occupied: 30.6 acres (12.4 hectares)

Plants

The Chestnut Oak / Mountain Laurel Forest has the look of a rugged survivor, with its deeply furrowed chestnut oak trunks towering over twisted branches of mountain laurel, all growing out of a cobble-strewn forest floor. Species diversity is low—you’ll see mostly chestnut oaks and mountain laurel—and the field layer contains little else besides chestnut oak seedlings.

Canopy Trees

The trees whose crowns intercept most of the sunlight in a forest stand. The uppermost layer of a forest.

- chestnut oak

- black oak (occasional)

- northern red oak (occasional)

- scarlet oak (occasional)

- white oak (occasional)

The Chestnut Oak / Mountain Laurel Forest is characterized, not surprisingly, by chestnut oak trees, noted for their distinctive leaves—egg-shaped with scalloped margins—and their strongly ridged bark.

Understory Trees

Small trees and young specimens of large trees growing beneath the canopy trees. Also called the subcanopy.

- blackgum

- red maple

- American beech (occasional)

- flowering dogwood (occasional)

- sassafras (occasional)

Blackgum is a tree commonly found beneath the canopy of chestnut oaks in this forest. It is one of the first trees to turn color in early October—a brilliant orange-red hue.

Shrubs, Saplings, and Vines

Shrubs, juvenile trees and vines at the right height to give birds and others a perch up off the ground but below the trees.

- mountain laurel

- hillside blueberry (occasional)

- black huckleberry (occasional)

- pink azalea (occasional)

- American witch-hazel (occasional)

- mapleleaf viburnum (occasional)

- common serviceberry (occasional)

Beneath the trees is a dense layer of mountain laurel shrubs with shiny leathery evergreen leaves and twisted trunks. Look for the striking white-and-pink flowers of mountain laurel in early June—they contrast remarkably well against the shrub’s dark green leaves. Pink azalea is another showy shrub that might be found here, with white to pink flowers that bloom in mid-spring, before the mountain laurel.

Scattered throughout this forest’s floor are small, deer-browsed hillside blueberry and black huckleberry bushes whose fruit ripens in summer. In the fall, the leaves of black huckleberry bushes turn a brilliant deep scarlet color. All of these shrubs are in the heath family.

Low Plants (Field Layer)

Plants growing low to the ground. This includes small shrubs and tree seedlings.

- chestnut oak seedlings

- green moss (occasional)

- partridgeberry (occasional)

- striped prince's-pine (occasional)

- white wood-aster (occasional)

The dense cover of mountain laurel and potentially extensive colonies of blueberry and huckleberry bushes cast a dark shade on the forest floor. Few wildflowers and grasses—either native or non-native—grow in their shadow on the coarse, infertile soils.

Non-Native Invasive Plant Species

Because of the harsh living conditions here, non-native invasive plants wouldn't normally be too much of a problem in this natural community. However, with some forest stands bordered by residential neighborhoods, there are constant seeds sources for non-native plants. Read about them on the Ecological Threats page.

Notable Variations

Today, American beech and red maple saplings and small trees are regularly encountered in the understory of this forest at Rock Creek Park, though they were almost certainly less common in the Chestnut Oak / Mountain Laurel Forest historically. Though these species are not likely to become as dominant in this community as in more mesic communities in the park, continued lack of fire may eventually result in American beech joining the canopy of the forest. This would change not only the species composition of the Chestnut Oak / Mountain Laurel Forest, but also its function as a fire-hardy forest on naturally fire-prone ridgetops.

This forest was intensively harvested for charcoal fuel production during early European settlement and the Civil War era. Telltale signs of historic logging include two or more trees sharing one trunk at the base (often the result of stump sprouting).

In some stands of Chestnut Oak / Mountain Laurel Forest that were intensely disturbed during the 1860s, mountain laurel is lacking. In fact, the understory has few native shrubs (none from the heath family) and very little ground cover for reasons that are unclear. We identify these stands, located on upper slopes or hilltops, as lower quality examples of the Chestnut Oak / Mountain Laurel Forest because the canopy is still predominantly comprised of chestnut oaks (though northern red oak may be a significant minority). One example of this can be seen on the north side of Fort DeRussey (where, unfortunately, linden arrow-wood* is abundant). (* indicates non-native)

Animals

Though the Chestnut Oak / Mountain Laurel Forest has one of the lowest species richness of any of Rock Creek Park’s forests, it still has much to offer the park’s wildlife. Chestnut oak acorns (over an inch in length) are among the largest of any eastern U.S. oak tree and are an important food source for many of the area’s animals.

The fleshy berries of the occasional hillside blueberry and black huckleberry bushes are eaten by squirrels, chipmunks, and many species of birds. The fruit of mountain laurel (a dry, woody capsule) doesn’t appear to be a significant food source for wildlife. Deer browse the twigs and leaves of all these shrubs. Although they don’t seem to care much for chestnut oak seedlings (except under duress), deer do eat the acorns of chestnut oak.

Sam Sheline

Because it occurs on some of the highest elevations in the park—places which get early morning sun—this community may be a good place to see migratory songbirds during spring and fall migration periods.

Wildlife finds shelter (from cold winter weather and from predators) in the dense evergreen foliage of mountain laurel. Red fox, a shy hunter, may frequent this forest.

Fallen dead trees, slowly returning their nutrients to the forest floor as they decompose, are great places for invertebrates and small mammals such as chipmunks and mice to find homes. Standing dead trees are preferred cavity nesting habitat for woodpeckers, squirrels, and many other animals.

back to top

Physical Setting

Area Occupied: 30.6 acres (12.4 hectares)

Stand Size: Small, isolated stands

Landscape Position: Some hilltops, ridges, and convex upper slopes

Soils: Dry, acidic, infertile, coarse, mineral soils

Geology: Primarily Potomac Formation (ancient river terraces)

Most of the few and scattered stands of Chestnut Oak / Mountain Laurel Forest in Rock Creek Park grow on hilltops, atop remnants of ancient river terraces consisting of cobbles, gravel and/or sand. These gravels and sands were deposited by a prehistoric river. Later, the land was lifted up by tectonic forces, leaving these deposits high and dry.

The soils on these hilltops and convex upper slopes are among the driest in Rock Creek Park because they are exposed to wind and sun from all directions. Rainwater percolates quickly through the coarse soil on these high surfaces, leaching away basic elements like calcium and magnesium and creating an acidic soil. Only a few plants thrive here due to the challenging conditions, which is why the natural community appears to consist almost entirely of two plant species well-suited to dry acidic soils—chestnut oak and mountain laurel.

Notable Variations

Gary Fleming

In Rock Creek Park, Chestnut Oak / Mountain Laurel Forest is usually found growing on the cobblestones of ancient river terraces that top some of the hills in Rock Creek Park and the surrounding area. This characteristic is not typical of Chestnut Oak / Mountain Laurel Forest elsewhere.

back to top

Natural Processes

Natural processes shape the land, create soil and topsoil, influence the water supply, and help determine the plants and animals that live in each natural community. Some natural processes act on large scales and affect more than one natural community at a time.

In This Community

Important natural processes in the Chestnut Oak / Mountain Laurel Forest include

- occasional fire

- exposure to sun, wind, and storms

- processes that create extreme dryness in the soils

- erosion

- canopy gap regeneration

In the Broader Landscape

In Rock Creek Park, two natural communities that have dry, acidic soil, and can survive (or even depend on) occasional fire are the Chestnut Oak / Mountain Laurel Forest and the Mixed Oak / Heath Forest. These two natural communities are grouped into a larger unit that ecologist refer to as the Dry Oak - Pine Forest Ecological System. An ecological system is a group of several natural communities that share many of the same natural processes and aspects of physical setting. By extension, they may also share many of the same plant and animal species. For example, these two natural communities both contain chestnut oaks, which thrive in dry soils and can survive fires.

No fires have occurred in Rock Creek Park in decades, but in the past, fires set by lightning and humans burned high and dry areas in the park, including areas now occupied by these two natural communities. Many of the plant species in these communities have built-in strategies for surviving occasional fires.

Ecological Threats

Each natural community faces ecological threats that could change its defining features, leading to its decline.

Non-Native Invasive Plants

The coarse, dry, sandy loam of the Chestnut Oak / Mountain Laurel Forest is not as hospitable to as many non-native invasive plants as some of the other natural communities in Rock Creek Park. Besides, dense colonies of native mountain laurel can make it difficult for all but the most hardy weeds to compete for root space and sunlight here. (* indicates non-native)

Ronald Kielb.

- autumn-olive (shrub)

- linden arrow-wood (shrub)

- winter creeper (vine)

However, where trails cut through this community, or where it borders residential neighborhoods, extra sunlight and rogue seeds can make their way into this community, giving other plant species a foothold. This is part of what is called edge effect.

Diseases, Pests, and Other Threats

Current and potential ecological threats for the Chestnut Oak / Mountain Laurel Forest in Rock Creek Park include these:

- Excessive deer browse: decimation of shrubs and oak seedlings

- Lack of fire: encroachment by fire-sensitive species like American beech; disease

- Gypsy moth: damage to oaks

- Dogwood anthracnose: decline of flowering dogwood

- Foot and horse traffic: erosion due to sparse field layer and thin duff (Exception: where mountain laurel shrubs add a protective layer.)

- Very hardy non-native invasive plants: competition with natives for soil nutrients, sunlight, and pollinators; degradation of animal habitat

Making a Difference

The well-being of natural communities depends not only on land managers, but on all of us—neighbors, visitors, fellow inhabitants of Earth!

Park Management

Park staff monitor and protect natural communities in many ways to help deal with threats from non-native invasive plants and insects, diseases, and more.

Here are a few ways Park staff are managing some of the ecological threats to the Chestnut Oak / Mountain Laurel Forest:

- Excessive deer browse: deer management plan in place since 2012 using lethal and non-lethal means 1

- Gypsy moth: bacterial and viral insecticides, naturalized fungus, release of parasitic wasps

- Potential arrival of diseases and invasive insects: Vigilance of Park staff and visitors

You Can Help, Too!

If you are interested in helping to take care of the natural communities of Rock Creek Park, here are some ideas:

Volunteer

- Learn about volunteering at Rock Creek Park.

- Team up with Rock Creek Conservancy, a citizen-based, non-profit organization that hosts volunteer restoration events for the benefit of the lands and waters of Rock Creek. Contact: www.rockcreekconservancy.org, (202) 237-8866, and info@rockcreekconservancy.org.

- Team up with Dumbarton Oaks Park Conservancy, another citizen-based, non-profit organization that hosts volunteer restoration events in partnership with the National Park Service to restore a 27-acre historic gem on one of Rock Creek’s tributaries in the nation’s capital.

In the Park

Trails:

Stay on trails and respect fences. Park staff sometimes put up fences to keep out deer or to discourage foot traffic in erosion-prone areas. You can help by staying out of fenced-in areas.

Pets:

Keep your pet on a leash so that it does not disturb animals or dig up plants. Clean up after your pet to help keep streams and rivers clean.

Keep Your Eyes Open:

Alert park staff if you see any of the following along the trail: diseased vegetation, infestation by non-native insects, invasion by non-native vegetation (especially Early Detection Rapid Response species), trash, unauthorized trails, or anything that looks amiss. Make a note of your location, take a picture if you can, and contact Rock Creek Park’s Chief of Resources Management at 202-895-6010.

At Home

Landscape with Natives:

Many non-native invasive plants started out as—or still are—popular landscaping plants, so you can help limit their spread by choosing native plants for your yard. If you do plant non-natives, remove seeds and berries before wind and animals spread them. English ivy won’t produce berries unless it’s climbing a vertical surface, so keep it off trees and walls.

Protect Streams:

Keep litter, fertilizer, pet waste, and yard waste off the streets where it can wash into the storm drains that lead directly to creeks. Consider installing a rain garden in your yard to slow down stormwater run-off and help recharge the groundwater.

Conservation Status and Classification

How vulnerable is a natural community to being eliminated? How similar or dissimilar is it to other natural communities? These questions are answered by naming and classifying natural communities, which helps us identify them and understand where each is found.

The U.S. National Vegetation Classification is the standard often used to classify natural communities.

Conservation Status

Conservation status indicates how vulnerable a natural community is. Conservation status can be measured globally and regionally.

Global Conservation Status: G5 – Secure

Subnational Conservation Status: D.C.: SNR – Not yet assessed

Classification

Official names reduce the confusion by providing a common language for talking about natural communities.

Abbreviated Common Name: Chestnut Oak / Mountain Laurel Forest

Common Name: Chestnut Oak Forest (Central Appalachian-Northern Piedmont)

Scientific Name: Quercus montana - (Quercus coccinea, Quercus rubra) / Kalmia latifolia / Vaccinium pallidum Forest

Scientific Name Translated: Chestnut Oak - (Scarlet Oak, Northern Red Oak) / Mountain Laurel / Blue Ridge Blueberry Forest

Classification Code: CEGL006299

Associated Ecological System: Dry Oak – Pine Forest Ecological System in Rock Creek Park

back to top