Viewpoint

Place-based and Traditional Products and the Preservation of Working Cultural Landscapes

by Rolf Diamant, Nora J. Mitchell, and Jeffrey Roberts

Preserving working cultural landscapes is one of the most complex challenges facing resource management professionals today. These landscapes, whether located within or adjacent to parks and other protected areas, contribute in a fundamental way to the heritage value and purpose of federal and other land conservation designations. The significance and authenticity of these landscapes often depends on the continuity and vitality of the cultural systems and traditional production that have created, over time, characteristic patterns of land use and a unique sense of place.

Many of these traditional land uses and their related products, which, less than a generation ago were taken for granted, are in danger of being destabilized and displaced. Changing demographics, escalating land values, the industrialization of agricultural production, and competition from global markets are all contributing to the unraveling of traditional social and economic relationships to the land. The speed and scope of these changes are unprecedented and have significant implications for the management of cultural heritage, including the fragmentation and development of cultural landscapes, the loss of market share for traditional products, and the concurrent erosion of regional identity and distinctiveness.

These challenges require some rethinking of the conventional relationships between parks, protected areas, and land stewards on one hand, and local communities and producers on the other. It is no longer enough to strive for a friendly co-existence. Stakeholders must be more intentional and proactive in defining their mutual interests and crafting new, cooperative strategies for enhancing the competitiveness and sustainability of those land practices and production methods that contribute to the long-term conservation of working cultural landscapes.

Authenticity, Sustainability, and Cultural Landscapes

Much has been written about the conservation dilemmas of historic cities, working cultural landscapes, and other dynamic cultural heritage sites, particularly in relation to authenticity.(1) Renewed discussion of authenticity of cultural landscapes followed their formal recognition in the United States in the late 1980s and internationally in the early 1990s when they were determined eligible for inscription on the World Heritage List.(2) Also in the early 1990s, an international dialogue on authenticity took place in Bergen, Norway, and Nara, Japan (both in 1994), followed by national discussions in several countries, including the United States (San Antonio, Texas, 1996).(3)

The resulting "Nara Document on Authenticity" and the "Declaration of San Antonio" provided insights into key issues and began to address some of the dilemmas posed by cultural landscapes. First, they acknowledged that the concept of authenticity evolves. David Lowenthal, a key figure in the discussions, noted that "each culture and entity accords authenticity a different meaning—a meaning which moreover shifts over time."(4) Reflecting on this concept, Herb Stovel, Secretary General of ICOMOS in the early 1990s, observed that—

The definition of cultural heritage is broadening… A concern for the monumental had implicitly focused the attention of conservators on essentially static questions—on the ways in which the elements of existing fabric could meaningfully express or carry valuable messages. A concern for the vernacular, or for cultural landscapes, or for the spiritual, has moved the focus toward the dynamic, away from questioning how best to maintain the integrity of the fabric toward how best to maintain the integrity of the process (traditional, functional, technical, artisanal) which gave form and substance to the fabric.(5) |

Christina Cameron, the director general of national historic sites for Parks Canada, suggested that a broad definition of cultural heritage requires a broad definition of authenticity. In her remarks in San Antonio, Cameron observed that—

definitions of heritage have broadened from single architectural monuments to cultural groupings that are complex and multidimensional… This wider definition of heritage necessitates certain distancing from bricks and mortar into the less well-defined "distinctive character and components"—a phrase added to the test of authenticity a few years ago when world experts worked on cultural landscapes criteria.(6) |

Cameron's observation is important because until the Nara conference, most aspects of authenticity had focused primarily on materials and physical form.(7) Article 13 of the Nara Document expanded that definition of authenticity—

Depending on the nature of the cultural heritage, its cultural context, and its evolution through time, authenticity judgments may be linked to the worth of a great variety of sources of information. Aspects of these sources may include form and design, materials and substance, use and function, traditions and techniques, location and setting, and spirit and feeling, and other internal and external factors. The use of these sources permits elaboration of the specific artistic, historic, social and scientific dimensions of the cultural heritage being examined.(8) |

Significantly, this expanded list of attributes for authenticity has recently been incorporated directly into the Operational Guidelines for Implementation of the World Heritage Convention used for evaluating nominations to the UNESCO World Heritage List.(9)

The participants at the 1996 San Antonio meeting not only concurred with this expansion of the concept of authenticity, but they also expounded on the implications for cultural landscapes—

We recognize that in certain types of heritage sites, such as cultural landscapes, the conservation of the overall character and traditions, such as patterns, forms, and spiritual value, may be more important than the conservation of the site's physical features, and as such, may take precedence. Therefore authenticity is a concept much larger than material integrity.(10) |

The San Antonio Declaration addressed the issue of authenticity in direct and more explicit terms—

Dynamic cultural sites, such as historic cities and cultural landscapes, may be considered to be the product of many authors over a long period of time whose process of creation often continues today. This constant adaptation to human need can actively contribute to maintaining the continuum among the past, present and future life of our communities. Through them, our traditions are maintained as they evolve to respond to the needs of society. This evolution is normal and forms an intrinsic part of our heritage. Some physical changes associated with maintaining the traditional patterns of communal use of the heritage site do not necessarily diminish the site's significance and may actually enhance it. Therefore, such material changes may be welcome as part of on-going evolution.(11) |

The San Antonio Declaration also addressed the issue of sustainability, recognizing that "sustainable development may be a necessity of those who inhabit cultural landscapes, and that a process for mediation must be developed to address the dynamic nature of these sites so that all values may be properly taken into account." UNESCO's Operational Guidelines likewise recognize that the management of World Heritage properties "may support a variety of ongoing and proposed uses that are ecologically and culturally sustainable," provided that "such sustainable use does not adversely impact the outstanding universal value, integrity and/or authenticity of the property."(12)

Preserving Landscape Character from Forest to Field

The National Park Service became directly involved in the issues of authenticity and sustainability in the course of developing a management plan for the historic Mount Tom forest at Marsh-Billings-Rockefeller National Historical Park near Woodstock, Vermont.(13) The Service investigated a number of cultural landscape stewardship strategies, including third-party certification of stewardship practices and various ways of using harvested wood in the fabrication of value-added forest specialty products. Third-party forest certification offered a way for the park and the Service to receive market recognition for good forest stewardship through credible, independent verification in the areas of forest practices, environmental impact, social impact, and civic engagement.

In August 2005, Marsh-Billings-Rockefeller became the first national park or national forest in the United States to be third-party certified by the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC).(14) That certification, moreover, is the very first public or private woodland certification substantially based on preserving cultural as well as natural heritage values. Products made from wood harvested from the park can now carry the FSC label.

Eastern National, the park's nonprofit partner, commissions local wood craftsmen to make a variety of products from that wood, for sale at the visitor center store. These products have added significance because of their clear association with place, heritage, sustainable management, local production, and craftsmanship. What is not yet clear, however, is how best to label and market these and similar products from around the National Park System in the United States. Among the options under consideration are separate or distinct "brands" associated with individual parks and places and affiliated or shared brands associated with the National Park System as a whole.

Knowledge Gained from International Exchange

The questions related to certification and value-added products at Marsh-Billings-Rockefeller prompted the park to learn more about similar efforts in other places. That inquiry resulted in a professional exchange between the National Park Service, parks in Italy (including the Nature Conservation Service and the Lazio Regional Park Agency), and protected areas in the Czech Republic. The program has enabled park managers on both sides of the Atlantic to share ideas and experiences and promote best practices in sustainable tourism and the stewardship of national parks.

Since 2000, Italy and the United States have been cooperating on the protection and management of national parks and other protected areas. Under the bilateral agreement, Italy hosted an international workshop, "Local Typical Products: Parks and Communities Working Together for a Sustainable Future," at Cinque Terre National Park and a number of protected areas around Rome managed by the Lazio Regional Park Agency. Seven National Park Service managers and nonprofit partners joined their Italian counterparts to discuss strategies for marketing and branding traditional products and crafts produced in and around parks as a way of strengthening economic sustainability, resource stewardship, and ties between local communities and park areas.

At Cinque Terre National Park, participants studied the recovery and economic revitalization of a World Heritage cultural landscape of steep coastal vineyards. Of particular interest was the park authority's program to facilitate the leasing of abandoned vineyards to maintain the production of the traditional Sciacchetrà wine and retain the historic hillside terraces.(Figure 1) Cinque Terre is also developing one of the world's most comprehensive programs of sustainable tourism based largely on its environmental quality brand. The quality brand is a voluntary certification instrument that encourages tourist sector businesses, including accommodations and restaurants, to meet specific environmental and heritage sustainability benchmarks in their operations.

|

Figure 1. An innovative land leasing program at Italy's Cinque Terre National Park is bringing abandoned vineyards back to life. (Courtesy of the authors.) |

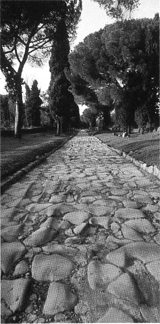

The second venue for the workshop was in the Lazio region, where the regional park agency (the first Italian regional parks authority devoted to managing a system of protected areas) showed how typical products and sustainable tourism strategies can be applied in urban park settings. These efforts were exemplified by the collaborative work in that region of the Parco Regionale dell'Appia Antica (Appia Antica Regional Park) and RomaNatura, the City of Rome's regional park authority.(Figure 2) RomaNatura has agreements with farmers in a 14,000-hectare greenbelt around Rome to preserve agricultural heritage, provide farm-based education experiences for Roman school children, and support local, sustainable, organic production for city markets. The greenbelt is the setting for the beginning of the Appia Antica (the Appian Way), the ancient Roman road to the port of Brindisi on the Adriatic Sea. The collaboration has helped stabilize traditional agricultural land patterns and protect the section of the Appian Way within the greenbelt against further urbanization. The Lazio Regional Park Agency has highlighted Roman specialties such as sheep's cheese in its atlas of typical park products, Natura in Campo (Nature Takes the Field).(15)

|

Figure 2. Agreements with area farmers to preserve agricultural heritage helps protect the Appian Way Regional Park outside Rome, Italy, against further urbanization. (Courtesy of RomaNatura.) |

By investing in the revitalization of traditional products, park managers in Italy are attempting to preserve an important sense of local identity and perpetuate local traditions and knowledge, even in the most densely populated cultural landscapes such as the Roman greenbelt. Many of these landscapes also serve as critical ecological corridors, buffer areas, and viewsheds. Managers are testing creative approaches to attract and employ young people, often producing or selling products with a clear social and economic agenda to strengthen the next generation's commitment to parks and heritage values. Workshop participants from both Europe and the United States found that "a well managed protected area can become a place where innovations in partnerships, integrated natural and cultural conservation, and thoughtful socio-economic strategies, can become a model for sustainable development."(16)

The Potential Role of Certification and Branding

At the invitation of the Quebec-Labrador Foundation's Atlantic Center for the Environment (QLF) and the United States Embassy in the Czech Republic, co-author and Marsh-Billings-Rockefeller superintendent Rolf Diamant spoke at a half-day seminar at the U.S. Embassy in Prague in 2006 on the marketing and promotion of local heritage products and their relationship to the conservation of parks and protected areas. Diamant also participated in a three-day stewardship workshop on the topic for park and cultural heritage professionals from the Czech Republic and Slovakia.(17) Czech and Slovak participants included craftspeople, small business owners, civic leaders, professionals, and volunteers working with local heritage organizations, museums, youth centers, schools, rural community development groups, environmental education centers, parks and protected areas, and greenways.

This exchange with the Czech Republic focused on a number of areas of mutual interest, specifically branding and certification systems, cultural authenticity, park related products, civic engagement, and public agencies as institutional consumers. The participants compared different national experiences in the use of independent evaluation and the application of certification systems in expanding consumer choice, encouraging sustainable practices, and guaranteeing greater public transparency in the management of park and protected areas. The workshop participants also touched upon other issues, including the authenticity of processes that help retain a continuity of landscape character, branding and co-branding, selling points and distribution systems, the cultivation of a stewardship ethic among young people, strategies for providing jobs and opportunities that would encourage young people to remain in rural areas, and the alignment of organizational procurement practices with organizational values in support of sustainability and products having a clear association with place, craftsmanship, public health, and resource stewardship.

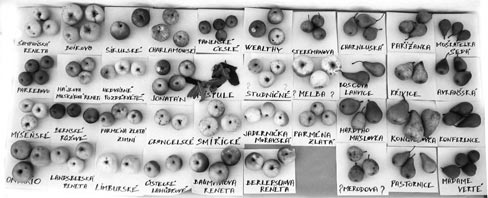

The group used the Bile Karpaty—the White Carpathian Mountains, an agricultural area on the Slovak border and the site of the workshop—as a case study. A landscape of mountain meadows, orchards, and sheep pastures, the White Carpathians are well known for traditionally produced and wood kiln-dried fruit, including many commercially unavailable heirloom varieties of apples and pears.(Figure 3) In the last 15 years, the area has witnessed a precipitous decline in traditional agriculture resulting from global commodity competition, the importation of fruit from other countries in Europe and Asia, and the industrialization of the fruit drying process in other countries using large-scale gas-fired kilns.

|

Figure 3. The White Carpathian Mountains abound in heirloom fruit varieties. (Courtesy of Traditions of the White Carpathians.) |

The sharp decline in orchard production and grazing has had major natural and cultural impacts on the White Carpathian region. Lost agricultural jobs have not been replaced, one result of which has been the steady migration of the region's young people to larger cities and towns in search of work. As abandoned mountain meadows transition to forest or non-agricultural uses, biodiversity decreases, threatening the high ecological values of the region. Meanwhile, the cultural connections to the region weaken, putting local foods, traditional methods and practices, and seasonal rituals at risk of disappearing.

The Centre for Sustainable Rural Development in the Carpathian village of Hostětin and its nonprofit sponsors have developed several intiatives to reverse this trend.(18) They include a nursery program to propagate orchard trees, a regional juicing and bottling facility for the production of organic and specialty fruit juices, a demonstration traditional wood-fired kiln for dried fruit, and a branding program—Traditions of the White Carpathians.(Figure 4)

|

Figure 4. This new regional juicing and bottling facility in the Czech village of Hostetin helps sustain local agricultural heritage. (Courtesy of Traditions of the White Carpathians.) |

The Czech Republic has one of the first national certification systems for heritage products—a spin-off of the Regional Environmental Center for Central and Eastern Europe's Natura 2000 "People for nature, nature for people," a public outreach project financed by the European Commission.(19) By successfully linking traditional land uses to biodiversity, the nonprofit Regional Environmental Centre (REC) Czech Republic is creating a broad-based alliance of local businesses, farmers and small producers, local and protected areas authorities, and other nonprofits and regional stakeholders.

Key steps in this certification project are—

1. Review and analysis of certification systems;

2. Development of integrated standards for regional products;

3. Establishment of an independent certification body;

4. Development of unified marketing and communication plans; and

5. Evaluation and selection of local fairs, markets, and retail selling points.

Certified products include food (cheese, cured meats, wine), crafts, and natural products (compost, mineral water, medicinal herbs). Certification involves an evaluation of product quality, environmental friendliness, regional origin, and uniqueness. The Czech Republic has also developed a sophisticated branding and graphics program that allows for regional variation within an overall national identity. Since the system's inception, the boundaries of the original participating regions have been expanded to embrace larger bio-cultural landscapes. The Czech alliance acknowledges how these broader, more integrated landscapes offer greater opportunity for success than initiatives limited to areas within delineated protected area boundaries.

The alliance anticipates that the program will help draw attention to protected areas within the Natura 2000 network of European protected sites and promote higher quality stewardship of the landscape and environment. That attention, in turn, will promote a more stable, sustainable model of tourism and rural economic development. Certification will also help all consumers distinguish between authentic products and substitutes from outside the region.

Creating an Atlas of Traditional Products in the United States

The lessons learned from these exchanges are now being applied to cultural landscapes across the National Park System in the United States. For example, the National Park Service's Northeast Regional Office and the Service's Conservation Study Institute in Woodstock, Vermont, are publishing Stewardship Begins With People: An Atlas of Places, People & Hand-Made Products.(Figure 5) The Atlas illustrates the many different ways national parks and other protected areas in the United States work in partnership with local communities to promote and market products that strengthen community ties to cultural landscapes and preserve threatened heritage values and authenticity. The Atlas is modeled in part on several publications produced by park colleagues in Italy and their nonprofit partners including Slow Food.(20) Each Italian park atlas beautifully illustrates an extraordinary array of authentic traditional food products—prodotti tipici—and identifies the park areas in which they are grown or made.(21)

An Atlas of Places, People & Hand-Made Products highlights the stories of friends, neighbors, and communities who practice a stewardship ethic and commitment to sustainability in and around national parks, heritage areas, and national historic landmarks. The publication describes examples from nearly two dozen national parks where people preserve authentic traditional cultures and significant cultural landscapes through their work and the products they make. The Atlas also recognizes recent initiatives undertaken by National Park Service concessioners and park nonprofit partners.

Stories appearing in the Atlas include—

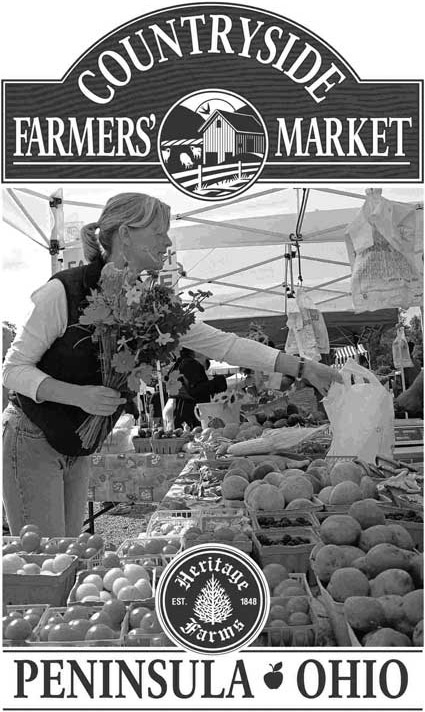

Cuyahoga Valley National Park, Brecksville, Ohio. Leasing farmsteads through the Cuyahoga Countryside Initiative, the park's effort to revitalize an Ohio landscape is well underway with three pilot enterprises demonstrating environmental stewardship while preserving traditional agricultural practices.(Figure 6)

|

Figure 6. New farmers markets are opening with producers who have long-term leases on historic farmsteads in Cuyahoga Valley National Park in Ohio. (Courtesy of Cuyahoga Valley National Park.) |

Canyon de Chelly National Monument, Chinle, Arizona. In 1864 the United States Army drove the Navajo people from their homelands and destroyed irrigation canals and well-established orchards. The Navajo returned in 1868 and brought peach orchard stock obtained from the Hopi. Canyon de Chelly National Monument is now home to 80 Navajo families, some of whom produce these heirloom peaches.(Figure 7)

|

Figure 7. Navajo families grow heirloom peaches in the Canyon del Muerto and other locations within Canyon de Chelly National Monument in Arizona. (Courtesy of Canyon de Chelly National Monument.) |

Haleakala National Park, Makawao, Hawaii. Formed to revive Hawaiian culture and stewardship practices, the nonprofit Kipahulu 'Ohana friends group has restored 14 l'oi, or taro patches, to active production. The friend's group plans to restore the entire 'ahupua'a, or tract of land from the mountains to (and including) the sea, to a self-sustaining community. The group wants to rebuild traditional 19th-century agricultural and aquaculture elements, remove invasive species, and reintroduce native and Polynesian plants.

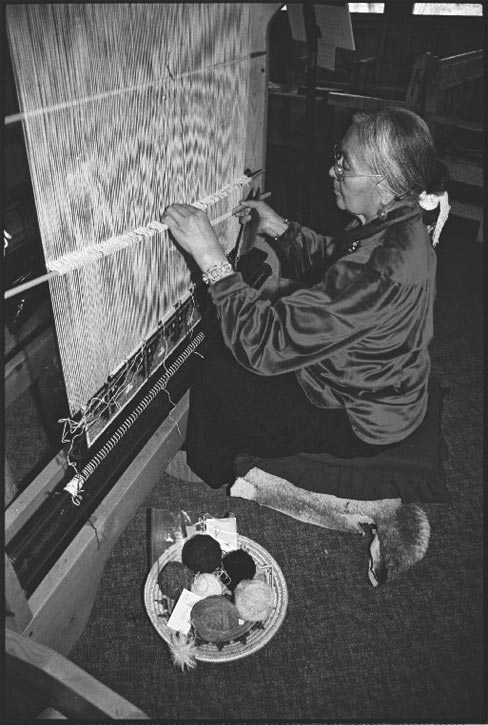

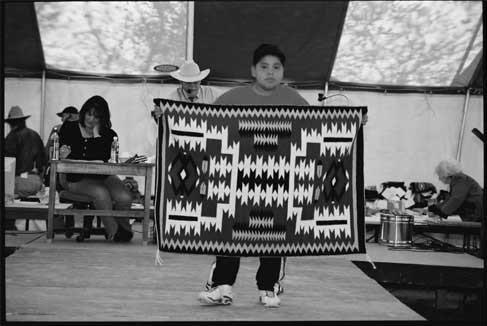

Hubbell Trading Post National Historic Site, Ganado, Arizona. This Arizona park fulfills its stewardship mission by supporting the local economy through collaboration with the Navajo Nation and the Western National Parks Association. Traditional weaving demonstrations and semiannual auctions help educate visitors about Navajo culture.(Figure 8)

|

Figure 8. Traditional Navajo weavings continue to be a mainstay at Hubbell Trading Post National Historic Site in Arizona. (Courtesy of the authors.) |

National Park Service Concession Environmental Management Program, nationwide. National park concessioners, including ARAMARK, Delaware North, Forever Resorts, and Xanterra, have green initiatives to increase the use of locally-grown and organic foods in their operations.

National Park Cooperating Associations, nationwide. These nonprofit partners play a growing role in marketing park products and developing and maintaining relationships with producers. The Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy's Warming Hut store on Crissy Field, for example, has a café menu that offers mostly organic or locally grown foods from around the San Francisco Bay Area.

Stewardship Begins with People

In order to preserve the authenticity and character of working cultural landscapes, communities must strike a delicate balance between continuity and change. Cultural traditions and associated land uses are critical to the equation, but these processes must be sustainable. Many cultural landscapes bear the imprint of 19th- and early 20th-century land use practices that have ceased to be economically viable. Consequently, the key to the successful conservation of these landscapes lies not in recreating the past at these sites, but in building on that past and crafting an economically viable future for these special places.

The case studies discussed above point to a new way of preserving the authenticity of cultural landscapes through the certification and marketing of local and regional specialty products. While often associated with traditional cultural practices, many of these products have close ties to contemporary activities that strengthen a sustainable economic relationship between people and the land. Over the last several years, park and protected area systems worldwide have become more cooperative and entrepreneurial in their interactions with the regions and local communities that have a critical role in the long-term stewardship of cultural landscapes.

Branding and certification are powerful tools for providing consumers with critical knowledge about the nature of the products they buy. They help individuals and organizations make free and informed choices that are in alignment with their values. Certification, however, is very fragile: Once a certification system has earned the public trust, it must constantly guard and renew that trust. It is very difficult, and in some cases impossible, to reestablish the credibility of a certification system once it has been compromised. If done carefully, a successful certification system enables people to make more educated choices between competing products with a clearer understanding of the intended and unintended consequences of their marketplace decisions.

The upcoming National Park Service publication, Stewardship Begins with People: An Atlas of Places, People & Hand-Made Products, is generating interest on both sides of the Atlantic. While conventional wisdom now suggests that "parks are not islands," parks and protected areas are only beginning to appreciate the many ways they can work with neighbors and partners to encourage stewardship of their cultural landscapes and achieve broader social benefits in the process. The idea has clearly arrived in many of the protected area systems of Europe and the National Park System in the United States, as evidenced by the surprising number of national parks and programs that have contributed stories and photographs for the Atlas.

Writer Wendell Berry has observed that "[most] people now are living on the far side of a broken connection."(22) The Atlas is one step in re-establishing a connection between parks and living cultures, between people and the food they eat, and between communities and the stewardship of park cultural landscapes and a more sustainable future for everyone.

About the Authors

Rolf Diamant is the superintendent of Marsh-Billings-Rockefeller National Historical Park in Woodstock, Vermont. Nora J. Mitchell is the director of the Conservation Study Institute and the assistant northeast regional director for conservation studies of the National Park Service. Jeffrey Roberts is the principal project advisor for Stewardship Begins with People: An Atlas of Places, People & Hand-Made Products.

Notes

1. In particular, we have drawn from Knut Einar Larsen and Nils Marstein, eds., Preparatory Workshop, Conference on Authenticity in Relation to the World Heritage Convention (Oslo, Norway: Directorate for Cultural Heritage, 1994); Knut Einar Larsen, ed., Nara Conference on Authenticity in Relation to the World Heritage Convention (Paris, France: UNESCO, 1995); and Gustavo Araoz, Margaret MacLean, and Lara Day Kozak, Proceedings of the Interamerican Symposium on Authenticity in the Conservation and Management of Cultural Heritage of the Americas (Washington, DC: US/ICOMOS, 1999).

2. National Register Bulletin 18 (1987) was the first to provide advice on the evaluation of cultural landscapes and was followed in 1990 by Bulletin 30 on rural historic landscapes. Bulletin 30 was the first to describe the importance of processes in landscape analysis—

Landscape characteristics are the tangible evidence of the activities and habits of the people who occupied, developed, used, and shaped the land to serve human needs; they may reflect the beliefs, attitudes, traditions, and values of these people. The first four characteristics are processes that have been instrumental in shaping the land, such as the response of farmers to fertile soils. The remaining seven are physical components that are evident on the land, such as barns or orchards. |

Linda Flint McClelland, J. Timothy Keller, Genevieve P. Keller, and Robert Melnick, National Register Bulletin 30: Guidelines for Evaluating and Documenting Rural Historic Landscapes (Washington, DC: National Park Service, 1990) 3-4. For an international perspective, see Bernd von Droste, Harold Plachter, and Mechtild Rossler, eds., Cultural Landscapes of Universal Value, Components of a Global Strategy (Jena, Germany: Gustav Fischer, in cooperation with UNESCO, 1995). The latter examines a series of case studies from all over the world following the inclusion of cultural landscapes in UNESCO's World Heritage Committee Operational Guidelines in 1992 (most recently revised in February 2005).

3. The international dialogue focused on the lack of attention paid to one of UNESCO's requirements that sites inscribed on the World Heritage List meet a "test of authenticity." The key references are Preparatory Workshop, Nara Conference on Authenticity in Relation to the World Heritage Convention, and Proceedings of the Interamerican Symposium on Authenticity in the Conservation and Management of Cultural Heritage of the Americas (see note 1 above).

4. David Lowenthal, "Criteria of Authenticity," in Larsen and Marstein, 36.

5. Herb Stovel, "Foreword, Working Towards the Nara Document," in Larsen, xxxiv. These discussions also stressed the importance of evaluating the authenticity of cultural heritage on a case-by-case basis and the impossibility of developing any fixed criteria for evaluation. Furthermore, the Nara conference highlighted the importance of working within an analytical framework and making the connection between heritage values and authenticity explicit. Stovel has argued that "without clarification of this fundamental relationship—cultural values and authenticity/integrity—between values and the genuineness of the manifestation of those values (physical or otherwise), advance in the clarity of thinking and practice will be difficult." In practice, therefore, it is critical to define the values of the landscape in question, which can include processes (traditions and land use), character, and physical components, in order to lay the groundwork for an authenticity evaluation. Stovel, "Foreword, Working Towards the Nara Document," xxxv; also Herb Stovel, "Notes on Authenticity," in Larsen and Marstein, 105.

6. Araoz, MacLean, and Kozak, 11.

7. Stovel describes the four areas of "design, material, workmanship, and setting" used to evaluate authenticity of World Heritage List property nominations in Larsen and Marstein, xxxiii. These areas are similar to those used in the National Register guidance on evaluation of landscape integrity. The exception is National Register Bulletin 30 on rural historic landscapes that identifies 11 characteristics, 4 of which are "processes that have been instrumental in shaping the land… [including] land uses and activities, patterns of spatial organization, response to the natural environment, and cultural traditions" and relates these to historic contexts and, presumably, to integrity. In reflecting later on the authenticity of landscapes, Dean Robert Melnick at the School of Architecture and Allied Arts, University of Oregon, and one of the co-authors of National Register Bulletin 30, noted that "standards for landscape integrity…must stem from an understanding of the landscape… That understanding requires, first, that the landscape is understood as a process as much as a product; that landscape is a verb as well as a noun." Melnick, "Strangers in a Strange Land: Dilemmas of Landscape Integrity," printed in compilation of draft papers for a conference "Multiple Views, Multiple Meanings," at Goucher College, Towson, Maryland, March 11-13, 1999.

8. "Nara Document on Authenticity" in Larsen, xxiii. Emphasis added.

9. Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention (Paris, France: UNESCO, 2005). The Guidelines are available online at http://whc.unesco.org/en/guidelines/, accessed January 3, 2005.

10. Araoz, MacLean and Kozak, xi.

11. Ibid., xii.

12. Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention, 28.

13. The Mount Tom forest, now a national historic landmark and part of the National Park System, is the oldest continuously managed woodland in North America and a storied landscape that illustrates the evolution of progressive forestry in the United States. The historical significance of the forest is directly related to the continuity of forest management and the legacy of careful stewardship.

14. The Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) is "devoted to encouraging the responsible management of the world's forests. FSC sets high standards that ensure forestry is practiced in an environmentally responsible, socially beneficial, and economically viable way." FSC standards for forestry stewardship "represent the world's strongest system for guiding forest management toward sustainable outcomes." Information about the FSC and its programs is available online at http://www.fscus.org/, accessed November 5, 2006.

15. Regione Lazio, Natura in Campo, Atlante dei prodotti tipici e tradizionali dei Parchi del Lazio (Nature Takes the Field, Atlas of Typical and Traditional Products of the Lazio Parks) (Rome, Italy: Assessorato all'Ambiente della Regione Lazio, 2006).

16. Federico Niccolini, Gay Vietzke, and Rolf Diamant, Protected Areas and Local Communities: Working Together for a Sustainable Future, International Workshop Final Report (Philadelphia, PA: National Park Service Northeast Regional Office, 2002).

17. The regional workshop, coordinated by the Quebec-Labrador Foundation, is part of a two-year program to promote stewardship of cultural heritage through a series of international exchange activities linking community-based initiatives in the northeastern United States, eastern Canada, and Central Europe. This program, "Stewardship of Cultural Heritage: An Exchange Program between Central Europe and North America," aims to strengthen the capacity of communities and local institutions in these regions to understand, maintain, and promote local cultural heritage in ways that support local and regional identity, cultural diversity, rural development, civic engagement, and the conservation of parks and protected areas.

18. The Center for Sustainable Rural Development, Hostětin, White Carpathians, is an educational and informational facility developed by the environmental nonprofit, Veronica. The center's program focuses on sustainable development projects and regional branding in the White Carpathian region.

19. Initially, the Czech Republic envisioned limiting its certification program to producers located within the boundaries of established protected areas but quickly decided to include larger regional cultural landscape and traditional heritage practices outside protected area boundaries.

The goal of the 2004-2005 "People for nature, nature for people" project was to "provide accurate and easily accessible information about the Natura 2000 Network in order to empower and involve citizens." Scottish Natural Heritage defines Natura 2000 as "a European network of protected sites which represent areas of the highest value for natural habitats and species of plants and animals which are rare, endangered or vulnerable in the European Community. The term Natura 2000 comes from the 1992 EC Habitats Directive; it symbolises [sic] the conservation of precious natural resources for the year 2000 and beyond into the 21st century." The Natura Network Initiative website (http://www.natura.org) offers detailed information on the initiative, its enabling legislation, and a list of participating sites. See Regional Environmental Center for Central and Eastern Europe (REF), "REF Country Office Czech Republic," http://www.rec.org/REC/Introduction/CountryOffices/CzechRepublic.html; Natura Network Initiative, http://www.natura.org/about.html; and Scottish Natural Heritage, "Natura 2000," http://www.snh.org.uk/about/directives/ab-dir03.asp, accessed September 24, 2006.

20. Slow Food is an international association founded in Italy in 1986 for the promotion of food and wine culture and agricultural biodiversity. The association opposes the "standardisation [sic] of taste, defends the need for consumer information, protects cultural identities tied to food and gastronomic traditions, safeguards foods and cultivation and processing techniques inherited from tradition and defend[s] domestic and wild animal and vegetable species." For more information, see the Slow Food Italian and International websites at http://www.slowfood.it and http://www.slowfood.com, accessed September 24, 2006.

21. Realizzato da Slow Food, in cooperation with Legambiente and Federparchi, Atlante dei produtti tipici dei parchi Italiani (Atlas of Typical Products of Italian Parks) (Rome, Italy: Ministero dell'Ambiente e della Cutela del Territorio, 2002); and Natura in Campo.

22. Wendell Berry, "In Distrust of Movements," Resurgence no. 198 (January-February 2000): 4.