Research Report

The Rhode Island State Home and School Project

by Sandra Enos

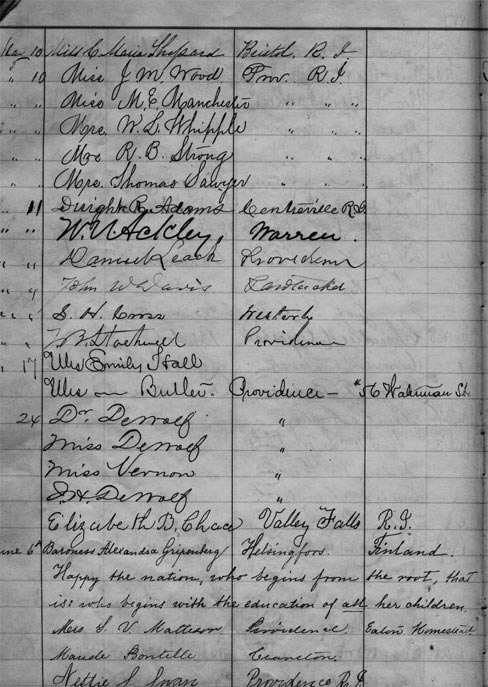

Established in 1884 by the Rhode Island General Assembly after extensive public debate, the Rhode Island State Home and School for Dependent and Neglected Children was one of the first public orphanages of the post-Civil War era in the United States. The State Home took in parentless and other children who had been living on poor farms, in private orphanages, or private homes under indenture arrangements and provided care in a wholesome and nurturing environment. Assisted by the Rhode Island Society for Prevention of Cruelty to Children and other overseers of the poor, the state-operated home attempted to break the cycle of pauperism by removing children from damaging environments, educating them, and placing them with good families.(Figure 1)

The State Home was based on an innovative child welfare model—called the Michigan model—that combined communal living with smaller "family" residential units. Elizabeth Buffum Chace, a Rhode Island reformer, wife of a textile factory owner, and a driving force behind the new orphanage and child welfare reform across the state, remarked of the model—

Life in it may be as much as possible like family life. There should be a large central building…a circle of cottages around the central house, all facing toward it, with plenty of space between them for free circulation of air…In each cottage I would place a good woman and a certain number of children: and this should be their home.(1)(Figure 2) |

The State Home also included a school and a working farm to support its operation.

Walnut Grove Farm, the site eventually selected for the new institution, was a considerable distance from the state's burgeoning welfare and correctional infrastructure. Over three decades, Rhode Island had constructed a state prison, workhouse, state poor farm, and a hospital for the incurably insane, all within a few miles of each other. Chace and fellow child welfare advocates felt strongly that in the interests of providing a wholesome environment for orphaned children the State Home had to exist separate and apart from any facilities having a taint of criminality or depravity.

Like many progressive reforms of the era, the home was born of great optimism. Within a few years, however, scandals related to the treatment of children and misappropriation of funds beset the home's board of overseers, and seemingly never-ending crises ultimately defined its nearly 100-year history. Several reports commissioned by the Rhode Island Governor's Office in the 1940s argued alternatively to shutter or expand the home in response to the changing needs of children and their families. When the home closed in 1979 amid accusations of warehousing children, it was one of the few remaining institutions of its kind in the United States.

In the late 1950s, Rhode Island College moved from downtown Providence to a site bordering the State Home. Although the College and the State Home, renamed in 1949 the Patrick I. O'Rourke Children's Center, were neighbors for more than 20 years, the two institutions had little interaction. The last residents left the O'Rourke Center in May 1979 when the state transferred the children to foster homes, independent living, or group homes. The Rhode Island Department of Children, Youth and Families used the cottages as office space for several years after the closure of the center. Rhode Island College took over the State Home property in 2002.

The State Home and School Project

Regional interest in the history of the State Home grew due to a series of seemingly unrelated events, now chronicled in the State Home and School website, that included the production of playwright Peter Parnell's adaptation of John Irving's novel, The Cider House Rules, by the local theatre company; the near demolition of the Yellow Cottage, the last surviving wooden building from the original State Home complex; and the discovery of log books, diaries, and infirmary journals that dated to the Home's establishment in 1884. These events led, in turn, to the formation in 2001 of a multi-year research, documentation, and preservation project. The project involved archeological excavations, special courses, conference presentations, reunions of former residents, oral history interviews, the reinstallation of replicas of the gates that once welcomed children to the home, a memorial to the State Home and School residents, an initiative to catalog and preserve the records of the State Home, the production of a new play by Sharon Fennessey, and the renovation of the Yellow Cottage.(Figure 3)

|

Figure 3. The recently renovated Yellow Cottage shown in this photograph is the State Home and School's only surviving wooden building. (Photograph courtesy of the author.) |

Former State Home residents have played a central role in the project, helping reconstruct the historical record and guiding project activities. They have expressed deep concern that people not forget about the State Home and School, and that people recognize it as part of the state's history. To that end, more than 30 former State Home residents, workers, and volunteers have shared stories and given oral history interviews of their experiences at the State Home. The interviews offer unique perspectives on the State Home and its legacy.

Through the oral histories, researchers can trace changes in institutional practices and child welfare policy and evolving concepts of childhood and children's needs. Former residents who spent considerable time at the institution referred to the State Home as their home and their neighborhood.(Figure 4) Others expressed the opposite, saying that although they had been a resident of the home, it was never their home and, as an institution, could never be. The home, it appears, simultaneously saved lives and made others terribly difficult.

The oral history effort culminated in the production of a CD of interview excerpts and an accompanying narrative titled "Let Us Build a Home for Such Children: Stories from the State Home and School."

With the research and documentation mostly complete, the State Home and School Project has shifted its focus toward drawing connections between the past and the present, between how people have cared for dependent and neglected children in the past and how people currently address the issue. The project plans to tell this story though its oral history and records archives, walking tours, public outreach, and continued research and development.

About the Author

Sandra Enos, Ph.D., is an associate professor of sociology at Bryant University in Smithfield, Rhode Island.

Note

1. L.B.C. Wyman and A.C. Wyman, Elizabeth Buffum Chace: Her Life and Its Environment (Boston, Massachusetts: W.B. Clarke Company, 1914), 85.