Guidelines for Restoring Cultural Landscapes

The Approach

Introduction

Rather than maintaining and preserving a landscape as it has evolved over time, the expressed goal of the Standards For Restoration and Guidelines for Restoring Cultural Landscapes is to make the landscape appear as it did at a particular—and most significant—time in its history. First, those materials and features from the “restoration period” are identified, based on thorough historical research. Next, features from the restoration period are maintained, protected, repaired (i.e., stabilized, consolidated, and conserved) and replaced, if necessary. As opposed to other treatments, the scope of work in Restoration can include removal of features from other periods; missing features from the restoration period may be replaced, based on documentary and physical evidence, using traditional materials or compatible substitute materials. The final guidance emphasizes that only those designs that can be documented as having been built should be re-created in a restoration project.

Identify, Retain, and Preserve Materials and Features from the Restoration Period

The guidance for the treatment Restoration begins with recommendations to identify the form and detailing of those existing materials and features that are significant to the restoration period as established by historical research and documentation. Thus, guidance on identifying, retaining, and preserving features from the restoration period is always given first. An overall evaluation of existing conditions should always begin at this level. The character of a cultural landscape is defined by its spatial organization and land patterns; features such as topography, vegetation, and circulation; and materials, such as an embedded aggregate pavement. This step must include archival research, survey of existing conditions and the development of period plans.

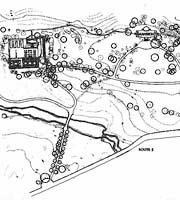

Restoration of the landscape as it appeared between 1830-1939 is the selected approach for the core area of the Vanderbilt Estate. Three historic periods in its development: 1895-1905; 1938-1941; and 1990-1991, with their character-defining spatial relationships and features were noted on period plans. A high level of accuracy and detail is essential to the success of any restoration project. (LANDSCAPES)

Protect and Maintain Materials and Features from the Restoration Period

After identifying those existing materials and features from the restoration period that must be retained in the process of Restoration work, then protecting and maintaining them is addressed. Protection generally involves the least degree of intervention and is preparatory to other work; it may be accomplished through permanent or temporary measures. Such actions could include the installation of temporary fencing around a vulnerable earthwork. Maintenance includes daily, seasonal, and cyclical tasks, and the techniques, methods and materials used to implement them. Repointing a stone burial marker from the restoration period is one example.

Once a restoration has been undertaken, an increased commitment to sustain the restoration period appearance will be necessary. Because of the dynamic nature of some features, particularly topography, vegetation and water, a landscape will exhibit cyclical changes, growth, and reproduction. Therefore, in some cases, maintenance efforts may need to be more elaborate.

Historic stones were protected and maintained during the recent restoration of the Alfred Caldwell Lily Pond in Chicago's Lincoln Park (NPS)

Repair Features and Materials from the Restoration Period

Next, when the physical condition of parts of features from the restoration period requires additional work, repairing is recommended. Restoration guidance focuses on those features and materials that are significant to the period. Consequently, guidance for repairing a historic material, such as masonry, again begins with the least degree of intervention possible, such as strengthening fragile or crumbling materials through consolidation (ex. Applying an inorganic substance such as barium hydroxide to friable masonry or applying epoxy consolidants to extensively deteriorated wood), when appropriate, and repointing with mortar of an appropriate strength. Repairing includes patching, splicing, or otherwise reinforcing materials using recognized preservation methods. Similarly, portions of a historic structural system of a footbridge could be reinforced using contemporary material such as steel rods. In Restoration, repairing may also include the limited replacement in-kind of extensively deteriorated materials or parts of features, and using surviving prototypes as a model. Using material which matches the old in design, color, and tute material is acceptable if the new material conveys the same visual appearance as the historic period. Creating a mold of an iron fence finial to replace another finial that is extensively deteriorated is one example.

A section of a historic wall at Stan Hywet Hall in Akron, Ohio, was in need of restoration. Here, the limited replacement of a section of the wall was undertaken utilizing surviving stone and stones that matched the old in form, size, and color. Compatible substitute material could also have been used. (NPS, 1993)

Replace Extensively Deteriorated Features from the Restoration Period

In Restoration, replacing an entire feature from the restoration period, such as an arbor, pool, or bench, that is too deteriorated to repair may be appropriate. Together with documentary evidence, any remaining physical fabric of the historic feature should be used as a model for the replacement. Using the same kind of material is preferred; however, compatible substitute material may be considered. When possible, new work should be unobtrusively dated to guide future research and treatment.

If documentary and physical evidence are not available to provide an accurate re-creation of missing features, the treatment Rehabilitation might be a better overall approach to project work.

The area known as the music pavilion at Tower Grove Park in St. Louis, Missouri, had been badly deteriorated including its central pavilion, marble busts, radiating walks, lawn areas and curbing. Utilizing photographic documentation, the pavilion and its associated landscape were restored to portray the pavilion as it would have appeared at a certain time. For example, the marble busts of eminent composers were replaced with pre-cast concrete replicas of the originals. (Tower Grove Park)

Remove Existing Features from Other Historic Periods

All cultural landscapes represent a continuum over time, but in Restoration, the goal is to depict the landscape as it appeared during a particular time in its history. Thus, work is included to remove or alter existing historic features that do not represent the restoration period. This could include features such as parking lots, modern farm equipment or timberform play structures. Prior to removing or altering spatial organization and land patterns; and features and materials that characterize other historic periods, they should be documented to guide future research and treatment.

This Demolition Plan, prepared as part of the restoration for the Tao House Courtyard, at the Eugene O’Neill National Historic Site in Danville, California, reflects the removal of features that were built after the period of significance. Those features removed, including walks, steps, patio and plant materials, may be attributed to a later design by landscape architect Ted Osmundson. (NPS)

Re-Create Missing Features from the Restoration Period

Most Restoration projects involve re-creating features that were significant to the landscape at a particular time, but are now missing. Examples could include a lost outbuilding, path or fence. Each missing feature should be substantiated by documentary and physical evidence. Without sufficient documentation for these “re-creations,” an accurate depiction cannot be achieved. Combining features that never existed together historically can also create a false sense of history. Using traditional materials to depict lost features is always the preferred approach; however, using compatible substitute material is an acceptable alternative in Restoration because, as emphasized, the goal of this treatment is to replicate the “appearance” of the cultural landscape at a particular time, not to retain and preserve all historic materials as they have evolved over time.

[top + right] This small footbridge in Central Park’s Ramble [above] has been re-created on the basis of historic documentation. The new bridge meets current code requirements, yet replicates the historic appearance, while utilizing compatible substitute materials. (Central Park Conservancy, NPS)

Special Considerations

(Accessibility, Health and Safety, Environmental, and Energy Efficiency)

These sections of the Restoration guidance address work done to meet accessibility requirements; health and safety code; environmental requirements; or limited retrofitting measures to improve energy efficiency. Although this work is quite often an important aspect of preservation projects, it is usually not part of the overall process of protecting, stabilizing, conserving, or repairing features from the restoration period; rather, such work is assessed for its potential negative impact on the landscape’s character. For this reason, particular care must be taken not to obscure, damage, or destroy historic materials or features from the restoration period in the process of undertaking work to meet code and energy requirements.

The selected treatment for the landscape at the J. L. Bush Storehouse Property, Greenwich, Connecticut, is restoration to the impressionist painters’ period. Here, sensitive grading preserved historic landscape features while providing access on the alignment of the original path. For example, grade relationships to the historic building and hedge have been retained. (LANDSCAPES)