Archeological Resources at Grand CanyonThe oldest human artifacts found are nearly 12,000 years old and date to the Paleo-Indian period. There has been continuous use and occupation of the park since that time.Prehistory of Grand CanyonThe earliest known period of occupation, the Paleoindian period, began at approximately 11,500 Before Present (B.P.) and lasted approximately 3,000 years to the end of the last ice age. During this occupation, small, mobile bands of people hunted megafauna such as mountain goats, ground sloth, and bison; and gathered wild plants. Paleoindian sites are extremely rare in the Southwest; one known site has been found within the Grand Canyon. Around 9,000 years B.P. environmental changes led to the expansion of differing environmental zones across the Southwest. During this environmental expansion, Paleoindians adapted to new environments and developed new subsistence strategies. The descendants of the Paleoindians, known as the Archaic, hunted smaller game and moved seasonally across the landscape to procure seasonal resources across vast territories. Tool kits included atlatls for dart throwing and chipped stone tools and groundstone tools such as metates and manos for plant processing. Archaic sites generally consist of temporary camps, rock art panels, caves, rock shelters, hearths or fire pits, grinding and processing tools, projectile points, flake debitage, animal and plant remains. Archaic sites have been identified throughout Grand Canyon (Fairley et al. 1994). Experimentation with horticultural subsistence began in the Southwest around 3500 B.P. with the appearance of maize agriculture. Horticultural subsistence strategies still relied heavily on hunting and gathering local resources, though maize, beans, and squash were planted in locations where seasonal flooding allowed for the germination and growth of cultivated plants. With the adoption of a more sedentary lifestyle, storage cists and granaries were used to store surplus supplies and pottery appeared by A.D. 500. The gradual shift to village life is referred to as the Formative Period, lasting from A.D. 500 to 1540 (Neal et al. 1999). During the Formative Period, the semi-sedentary occupants of Grand Canyon began producing baskets, sandals, and storage features such as slab-lined cists and granaries. This tradition first appears in the Southwest around A.D. 1. The period, often viewed as a transition to agriculture, marks the beginning of horticultural subsistence strategies. Initially, dwellings appeared as shelters in overhangs and caves. By A.D. 500, circular pithouses appear in small aggregates, suggesting the beginning of village life. Pottery appears at this time, often graywares with black painted designs. In eastern Grand Canyon, these occupations have been associated with Cohonina peoples (Schwartz 1969). The appearance of ceramic vessels, both jars and bowls, seems to be associated with an increase in sedentary lifeways and the development of habitation structures. These structures began with semi-subterranean pithouses and shifted to above ground masonry room blocks or pueblos. The bow and arrow replaced the atlatl, and the geographic region of resource procurement expanded. A more stable subsistence strategy of combined agriculture and hunting and gathering allowed for the continued aggregation of individuals into small villages or hamlets. Ceramic technology and design styles became more elaborate and new technologies developed, including the use of cotton for textiles. Surface storage rooms developed into above ground habitation structures and later, contiguous pueblos in some locales. By A.D. 900 along the river corridor, Puebloan peoples were cultivating maize, evidenced by the presence of corn pollen on living floors (Schwartz 1969). Both Tusayan Gray Ware and Tusayan White Ware ceramics increased in eastern Grand Canyon, signaling the expansion of the Kayenta Branch from the southeast. During the later portion of the 10th century, masonry surface pueblos and semi-subterranean kivas appeared. Population growth was gradual, with the addition of single rooms to existing structures that resulted in linear pueblos of two to seven contiguous rooms. Ceramics continued to be dominated by Kayenta wares, with a gradual increase in ceramics from their northern neighbors, the Virgin Branch. While ceramic styles remained relatively stable, after A. D. 1100 an abrupt change in architecture occurred in eastern Grand Canyon. Habitation structures became more interspersed with storage rooms and bins, fire pits, and increased use of outdoor activity areas (Schwartz 1969). Pottery distributions continued to increase in Virgin Branch styles. Habitation appears to have moved to higher terraces, perhaps to fully exploit regions adjacent to water sources for increased fertile agricultural productivity. According to Schwartz (1969), it appears that rather than population influxes from different indigenous groups, trade connections with the north were more fully developed in conjunction with localized ceramic traditions. It is believed that by A.D. 1300, semi-nomadic, non-puebloan peoples also occupied the river corridor of Grand Canyon. These Pai and Paiute hunter-gatherers had a stable subsistence economy based on combined agriculture and hunting and gathering, supplemented by trade. Dispersed settlements included wickiup rings, rock shelters, extensive roasting complexes that included ceramics and abundant flake stone tools and debitage. It is also believed that these hunter-gatherers made use of perishables such as baskets, mats, sandals, and twine. These ancestors of the present day Hualapai and Havasupai continued to seasonally utilized both the rim and river corridor until interdiction by the U. S. Government. In addition to indigenous populations, Europeans also traversed the Grand Canyon. The historic period includes visitation by Spanish Missionaries, mining and tourism entrepreneurs, and more recently, hydroelectric power exploration and production. The prehistory of the river corridor in Grand Canyon closely follows the sequences of regional occupation and abandonment generally agreed upon by southwestern archaeologists. Localized variation in habitation, construction, and ceramic technologies are to be expected. No doubt the inhabitants of Grand Canyon were influenced by the same climatic changes that occurred across the entire southwest. Archaeologists also assume that population expansion along the river corridor itself was a direct result of population growth along the rims of the Grand Canyon. Because there are only a limited number of entrance and exit points into Grand Canyon, a majority of the sites recorded at permanent water sources and along access routes consist of multiple occupations through time.

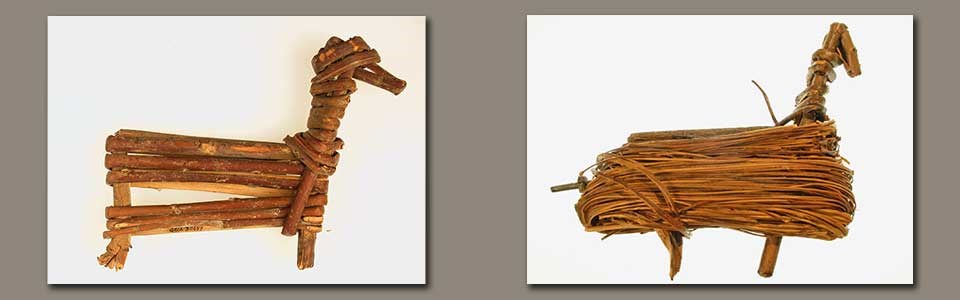

Split-Twig Figurines

--While their exact function remains a mystery, recent research suggests that split-twig ----figurines were totems associated with the Late Archaic hunting and gathering culture. Their occurrence in remote, relatively inaccessible uninhabited caves indicates that these figurines were not toys. They are usually found under rock cairns, indicating careful placement.

Take a virtual tour Grand Canyon Archaeology Virtual TourDiscover ancient places within the Grand Canyon where people lived long ago.What did the archaeologists find during the first major excavation to occur along the Colorado River corridor in nearly 40 years? Interactive 360° photos, show archaeologists at work, along with their tools, such as shovels, trowels, screens and buckets. https://www.nps.gov/features/grca/001/archeology/index.html

Visit our keyboard shortcuts docs for details

Discover ancient places within Grand Canyon where people lived long ago. What did the archeologists find during theses major excavations along the Colorado River ? Related Information Grand Canyon National Park Archeological Resources The River Monitoring Program generates data regarding the effects of Dam operations on historic properties, identifies ongoing impacts to historic properties within the APE [Area of Potential Effect], and develops and implements remedial measures for treating historic properties subject to damage.

Visit our keyboard shortcuts docs for details

Located three miles west of Desert View, Tusayan Ruin provides a look into the lives of the ancestral Puebloan people who called Grand Canyon "home" 800 years ago.

Grand Canyon's Associated Tribes

Learn more about Grand Canyon' associated tribes on Arizona State University's Nature, Culture, and History at Grand Canyon website.

Visit the Tusayan Ruins and Museum

Visit the 800-year-old ancestral Puebloan site and learn about the people who called this place home. |

Last updated: July 30, 2020