Historical Background

THE Constitution—which ultimately emerged from

the crucible of debate and conflicting interests—was a bundle of

compromises and an imperfect instrument. Of the 39 delegates who

subscribed to it, few expressed complete satisfaction with their work.

And some even doubted it would endure. The public was even less

sanguine. The advocates of the instrument labored for nearly a year

before enough States ratified it and made it the law of the land. Yet,

once the document went into effect, it soon became the pride and bulwark

of the Republic.

In most respects, the Constitution sprang from the American colonial, Revolutionary, and Confederation experiences. For example, the idea that a nation was bound by a constitution that limited and defined the powers of government had long been part of the English political consciousness. But, beginning with the colonial charters, Americans preferred written constitutions, which both citizens and officials could refer to for guidance. Liberties were not to be trusted to the benevolence of rulers, and the discretion of magistrates and legislators was to be restricted to fixed principles. Government was regarded as a necessary evil that needed to be circumscribed.

In other words, the basic institutions of constitutionalism were being established long before the War for Independence and the drafting of the first State (1775-80) constitutions, the Articles of Confederation (1778), and Federal (1787) Constitution. These institutions were reflected in the royal charters, concessions by the King and royal proprietors, and legislative acts initiated by the people's representatives. All these recognized the basic importance of personal liberties in written form.

|

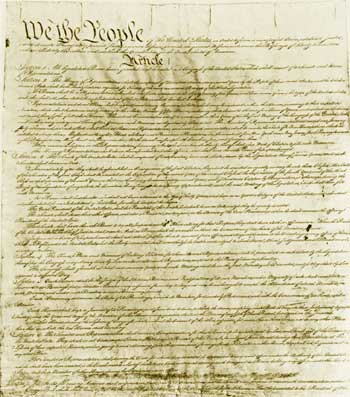

| Constitution of the United States (first page). (National Archives.) |

|

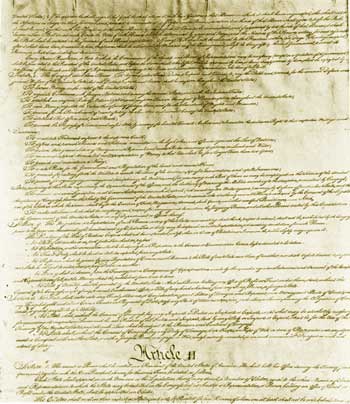

| Constitution of the United States (second page). (National Archives.) |

|

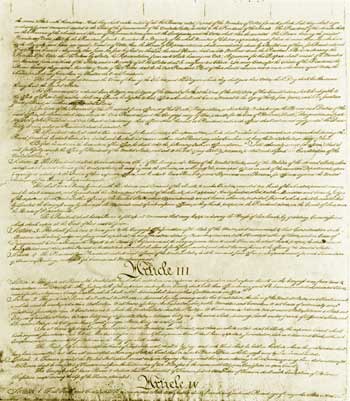

| Constitution of the United States (third page). (National Archives.) |

|

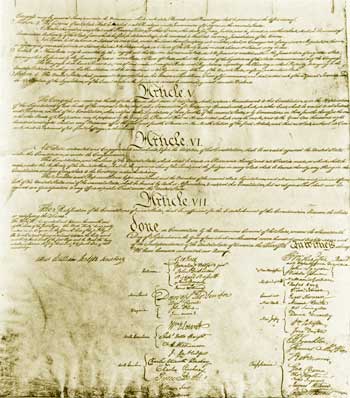

| Constitution of the United States (fourth, or signature, page). (National Archives.) |

|

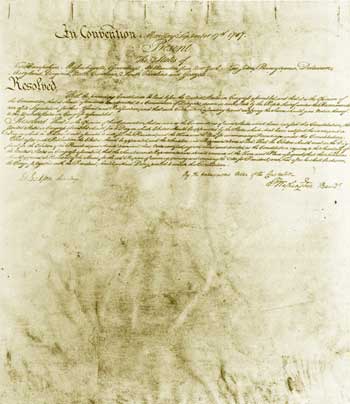

| Constitution of the United States (fifth, and last, page, known as the "Resolution of Transmittal to the Continental Congress"). (National Archives.) |

The system of checks and balances, which the framers utilized to prevent the dominance of any one branch of the Government over any other and to maintain stability between the States and the national Government, was traceable to the ideas of the French political theorist Baron Charles D. Montesquieu and to the English conception that a balance of power among the King, the aristocracy, and the House of Commons prevented the undue ascendancy of any one group or majority. Also affecting the Constitution were other aspects of English law and thought, especially the ideas of John Locke. Included among those was the belief of apostles of the Enlightenment that natural laws governed man as well as the universe. Various additional European influences and Greek and Roman political concepts also made their mark on the Constitution.

Within that framework, however, the instrument was the product of a body of men who were experienced in self-government and were practical politicians. Confronting a definite and unique situation, for the most part they shunned abstract political speculation, though they drew on the lessons of history and political theory. Principle, expedience, and compromise all played roles, and their interplay was incredibly complex. A new frame of government was created that in its totality embodied much that was unprecedented and that has served as a model for constitutions since established by various other countries.

Considering all the difficulties they encountered in fashioning the Constitution, its makers could not conceivably have covered all basic topics nor treated those they did without ambiguity. In many cases, the ambiguity was deliberate to prevent further disagreement in the Convention.

|

| Many of the ideas expressed in the Constitution are traceable to European thinkers. Two of those who exerted the greatest influence were John Locke (left) and Baron Charles D. Montesquieu (right). (Locke, detail from engraving (undated) by J. Posselwhite, after a portrait by Godfrey Kneller, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; Montesquieu, detail from engraving (undated) by H. C. Muller, after a portrait by Deveria, National Portrait Gallery.) |

Above all, the framers could not be expected to be visionary enough to foresee and address all major matters that might be of future concern to the United States, especially subsequent political, economic, and social complexities. Many questions were left to be arbitrated and answered over the course of time. For example, the founders did not furnish mechanisms for the acquisition of new territory, establish specific terms for the admission of new States, specify the number of judges who would sit on the Supreme Court, or indicate what major departments should be created. While the framers extended the powers of Congress by specific grants to the maximum degree they felt was safe, by means of the "general welfare" and "elastic" ("necessary and proper") clauses they made possible augmentation of the enumerated powers of Congress. The broad definition of Presidential responsibilities has also allowed a similar amplification. To provide for reform, omissions, unforeseen factors, and changes, the Founding Fathers offered a system of amendments.

Other revisions or additions have been made by legislation or custom—in the "Unwritten Constitution." This includes such elements as the power of the Supreme Court to decide on the constitutionality of Federal and State laws, a practice implied in the Constitution but originated by Chief Justice John Marshall; and the establishment of the Presidential Cabinet, a group of advisers made up of the heads of executive departments. The 22d amendment, which prohibits the President from serving more than two terms, is an example of a custom once part of the Unwritten Constitution that has been incorporated into the document.

This elasticity, or capacity for expansion, while making it certain that interpretation of the Constitution would generate disputation over the years, has at the same time allowed it to adjust to changing circumstances and endure throughout the decades.

During that time, the instrument, one of the oldest written charters of government, has won the laudation of the world. British Prime Minister William Gladstone effusively called it the "most wonderful work ever struck off at a given time by the brain and purpose of man." William Pitt, the younger, who had occupied the same office, said the document would be the "pattern for all future constitutions and the admiration of all future ages." But signer Robert Morris provided a more realistic appraisal: "While some have boasted [the Constitution] as a work from Heaven, others have given it a less righteous origin. I have many reasons to believe that it is the work of plain, honest men, and such, I think, it will appear."

|

|

http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/constitution/introg.htm

Last Updated: 29-Jul-2004