Historical Background

WORKING late on the night of September 17 and

possibly into the morning hours to make the final revisions in the type

he had been holding since September 13, the printer had available for

Secretary Jackson on the morning of the 18th a large quantity,

apparently 500, of official six-page copies of the Constitution. For

about a day, this version, which contained one error (1708 instead of

1808 in Article V), was the only printed one.

Secretary Jackson departed on the morning of the 18th for New York, where he arrived the next afternoon. The following day, he transmitted to Secretary Charles Thomson of the Continental Congress the engrossed copy of the Constitution; the accompanying documents, including George Washington's letter of transmittal; and undoubtedly the official printed copies. That same day, the engrossed or one of the printed copies was read to Congress, but it took no action and set the 26th as the day on which the instrument would be considered.

|

| A Philadelphia newspaper's account of the adjournment of the Convention. (Pennsylvania Packet (Philadelphia) September 18, 1787. Library of Congress.) |

Meantime, the Constitution had apparently been read to the public for the first time, and the Philadelphia newspapers had been busy. At the September 18 meeting of the Pennsylvania assembly, in the east room on the second floor of Independence Hall, Speaker Thomas Mifflin read it before the legislators and numerous spectators. Although no copies have survived, possibly the Evening Chronicle published the document on Tuesday evening, September 18. All other five newspapers in the city definitely did the next day. Only the version in Dunlap & Claypoole's Pennsylvania Packet contained a "pure" text, for it included the 1708 error. All the other four renditions corrected this mistake and by error or design made additional changes, including those in abbreviation, spelling, and punctuation.

From these have stemmed a proliferation of printings, both in the United States and abroad, that have continued right up to the present day—in newspapers, magazines, broadsides, pamphlets, handbills, leaflets, almanacs, and books.

IN Article VII and in the fifth-page "resolution of

transmittal" to the Continental Congress, the Convention provided a

procedure for making the Constitution the law of the land. Each State

would call a convention, whose delegates would be elected by the voters.

After nine of these groups ratified, the new Government could begin

operation.

On September 26, 1787, the Continental Congress, including 10 or 12 men who had been in attendance at Philadelphia, began considering the document. A vociferous minority of Members raised numerous objections during 2 days of debate. They charged that the instrument was too sweeping and clearly exceeded the amendment of the Articles of Confederation that had been authorized; criticized omission of a bill of rights; and attacked various details. It was even proposed that a series of amendments be attached to the Constitution before it was submitted to the States. But on September 28 supporters and critics of adoption compromised on a noncommittal forwarding of the new governmental framework without change to the State legislatures, which were to set up the conventions. The copies sent to the States were apparently from a new printing that John Dunlap had subcontracted to John McLean (M'Lean), a New York City newspaper publisher.

|

| One of the first newspaper printings of the Constitution. It appeared in the Packet, published by Dunlap & Claypoole, who were also the official Convention printers. (Library of Congress.) |

DURING the yearlong political struggle that ensued in

the States prior to the establishment of the new Government, two

distinct factions emerged. The advocates of the Constitution adopted the

name "Federalists" and cleverly pinned on their opponents the label

"Antifederalists," which had formerly described those who had fought

against formation of the Confederation. Realizing that the "Anti" prefix

placed them in the role of obstructionists and that they had no positive

plan of their own to offer, the Antifederalists not only used the name

reluctantly but also often tried to reject it and to transfer it to the

Federalists, whom they claimed better deserved it.

With good reason. The so-called Antifederalists were not really opposed to a federation; and many of them, especially those who advocated immediate amendment of the Constitution, believed they were the true defenders of the federal system. Most of them favored preservation of the Confederation. One of their strongest objections to the Constitution was that, in their minds, it established a national rather than a federal Government. For these reasons, they made a vain attempt to claim the Federalist name, which they sometimes even employed in the titles of their tracts or in the pseudonyms they frequently attached to them.

Thus, the two terms are grossly misleading. The Federalists might more aptly have been called "Centralists" or "Nationalists" and the Antifederalists "Federalists" or "States righters." Furthermore, despite the bitterness of the ratification battles, the two designations imply a greater degree of basic antithesis than actually existed. Both sides sought an effective national Government and safeguards against tyranny, but they differed on the efficacy of specific constitutional provisions in achieving those goals. Use of the two labels is also unfortunate in that it falsely indicates a compartmentalization that was lacking. Within each of the two camps, a wide range and strong shades of opinions were manifested and some people switched allegiance.

The composition of the two groups differed in practically every State. A host of geographical, economic, social, and political factors determined alinement. Although clear-cut divisions were blurred, the Federalists loosely encompassed those whose livelihoods were significantly linked to commerce, such as merchants, shippers, urban artisans, and farmers and planters residing near water transport, as well as members of the professions and creditors. All these groups were mainly concerned about the economic benefits and property safeguards against State actions a stronger central Government would provide. Many of the leaders enjoyed national political experience and had served as officers during the War for Independence. Usually more worldly than their Antifederalist counterparts, many had been educated abroad and were more experienced in foreign affairs.

The Antifederalists tended to be more locally oriented. They included residents of isolated villages and towns, small farmers, frontiersmen, and debtors. These classes usually preferred maximum individual and local autonomy rather than the expansion of governmental power.

Exceptions to these generalizations, however, were numerous. All rich merchants and planters did not necessarily favor the Constitution, nor poor farmers and mechanics oppose it. Nor was the eastern seaboard totally Federalist and the West completely Antifederalist. Sometimes a healthy minority of divergent opinion existed among similar groups within a particular section of a State or region. Several Antifederalists were well-to-do creditors, and some Federalists were heavily in debt. Back-country farmers in Georgia, concerned about the Indian and Spanish threats, backed a powerful central Government. Local circumstances also contributed to the Antifederalist stance of a number of large estate owners in the Hudson River area of New York State.

The Antifederalists were as a whole probably more democratic than the Federalists, but many of the leaders were members of the aristocracy and maintained reservations about democracy; ordinarily only the poorer and less sophisticated Antifederalists espoused it. But neither side used the word "democracy" very often. When the Federalists did so it was usually with scorn; and, when the Antifederalists did so, it was more likely with favor.

The Antifederalists were saddled with numerous disadvantages. They were not only less well organized and united than the opposition, but they were also on the defensive because they were objecting to a bold and comprehensive new plan of government.

Many of them believed some changes in the Articles of Confederation were needed, especially in the field of commerce, but they could not effectively object to all those recommended in the Constitution.

The Antifederalists also had fewer leaders of national stature. They included only six men who had attended the Constitutional Convention: Luther Martin, John F. Mercer, Robert Yates, John Lansing, Jr., George Mason, and Elbridge Gerry. Only the latter two had stayed for its duration though they, too, had not signed the Constitution. Other members of the group were Richard Henry Lee and Benjamin Harrison of Virginia and Samuel Chase of Maryland, all signers of the Declaration of Independence; Gov. George Clinton of New York; and Patrick Henry and James Monroe of Virginia. Like Henry, Lee had been elected to but did not attend the Convention. He chose not to do so because he felt it would be improper for Members of the Continental Congress to take part. He was the author of a powerful statement of the Antifederalist case, Letters From the Federal Farmer to the Republican.

On the other hand, in the front rank of the Federalists were practically all the delegates to the Convention, including every one of the signers of the Constitution, among them such preeminent men as Washington, Franklin, Madison, and Hamilton; Randolph, who switched over from the Antifederalist side; signer of the Declaration Benjamin Rush; and diplomat John Jay, Jr.

The cohesive Federalists evolved a concrete program, conducted a vigorous and well-tuned campaign, and benefited from strong newspaper support. Skillfully presenting their case, they wisely chose to emphasize issues on which national consensus could easily be obtained and ignored those that would aline section against section, rich against poor, or debtors against creditors. They also worked more quickly than their opponents and organized more effectively. They were more deft in parliamentary maneuvering at the ratifying conventions. The many compromises they had made in the creation of the Constitution made it more defensible and also more acceptable to various groups that might otherwise have opposed it.

|

| Title page of the original edition (1787) of Richard Henry Lee's Letters from the Federal Farmer to the Republican, a leading Antifederalist tract. (Historical Society of Pennsylvania.) |

But the Federalists, too, faced several problems. They needed to convince the country that a totally new frame of Government was needed. And many of those they were trying to convince were not sufficiently aware of the Nation's domestic and international problems and thus did not understand the need for and value of the remedies recommended. A large part of the populace, especially because of the recent clash with Britain, was opposed to any more change, to a strong central Government, and to the imposition of too many controls on State and local governments. Then, too, these governments resented any augmentation of national power at their expense.

The Federalists also faced a significant handicap in that they needed to win the ratification contests in at least nine of the States, and particularly in the large and strategic States of Virginia and New York, as well as Massachusetts and Pennsylvania. The Antifederalists, on the other hand, could thwart the whole effort by winning any five States, and probably could accomplish the same if they won in either New York or Virginia.

The arguments of the Federalists and Antifederalists—voiced and written in speeches, letters to newspaper editors and others, tracts, pamphlets, and at the State conventions—ranged from the theoretical to the practical and from the low-keyed to the highly emotional. Regional, sectional, and individual differences were demonstrated.

The Antifederalists tended to defend the Articles of Confederation, though they felt they needed to be modified, or advocated a weak central government that would allow maximum participation of the people and insured State sovereignty. Most Antifederalists insisted that conditions were not as desperate as the Federalists painted and questioned the need for a drastically new Government. They felt the Constitution was too extreme a remedy for the problems of the Confederation. Thus, if they could not stop ratification of the document entirely, they committed themselves to its immediate revision by a second convention or by amendment.

Other fears were stressed: that many of the framers had ulterior motives, a charge that seemed plausible because of the secrecy of the Convention and the rush to ratify the Constitution; that the proposed new government, especially with its strong Executive and powerful Senate, would be more tyrannical than that of the British had been and would result in a monarchy or aristocratic rule; that, lacking a bill of rights, as the Constitution did, it would destroy personal liberties; that the checks and balances written into the document were insufficient to protect the rights of State and local governments; that power was being transferred from the many to the few to inhibit or prevent future political change and reform; and that the large States would overpower the small ones.

Patrick Henry, who had declined to serve in the Convention because he "smelt a rat," began his objections with the first three words of the Constitution. Who, he wondered, were the delegates to say "We the People"? They should have said "We the States." Otherwise, the Government would no longer be a compact among equal States but a "consolidated, national government of the people of all the states."

Another charge was that the Convention had ignored or exceeded its instructions from Congress to amend the Articles of Confederation, had abandoned their federal basis, and violated procedures for their amendment with the nine-State ratification requirement. The Federalists were also accused of having ties with foreigners and with being sympathetic to a monarchy.

The Antifederalists rarely mentioned national security or foreign affairs. Even when they did, they did not deny Federalist arguments but contended that the good that might be gained in these fields by the Constitution would be offset by the disadvantages of such great central power and that amendments to the Articles of Confederation could bring about the necessary improvements. There would be enough time to provide an adequate defense once war broke out, and direct federal taxation could be resorted to if the old requisitioning system on the States failed to work.

Another point made by some Antifederalists was that a single government would be unable to rule a country as large and complex as the United States, which was far larger than any earlier federation, without becoming tyrannical. Regional confederations were considered to be more effective.

Some aversion to the Constitution was sectional in nature. For example, the Southern States feared the commerce clause would allow the Northeastern States, which owned and built most of the ships, to control their trade. The maritime States might obtain a monopoly by securing the passage of navigation laws restricting commerce to American ships or of tariffs unfavorable to the South. It was felt, too, that the Senate might use its treaty power to surrender free navigation of the Mississippi, which was critically important to the region, as well as to the West.

The Federalists, who asserted that the Convention had followed the spirit of its congressional instructions, stressed the deficiencies in the Articles of Confederation. Viewing the Constitution as a workable compromise of divergent opinions and granting that it was not perfect, its advocates held that it was nevertheless vastly superior to the Articles and that subsequent amendments could purge its imperfections. Constitutional supporters, warning that delays in ratification would result in disastrous disunion and that a second convention would likely destroy the agreements already achieved, fought for quick and unconditional ratification.

Denying that the government they proposed would sweep aside States rights, the Federalists pointed out that all powers not specifically granted to it, like the protection of individual rights, were by implication State prerogatives; and that under any system of government large States could usually overpower small ones but that they would be less likely to do so within the framework of a friendly and voluntary union.

As a counter to Antifederalist charges that a federation would not work in such a huge country, the Federalists argued that the larger a federation was the less chance there would be that any of its members could dominate the others. Furthermore, the system devised at Philadelphia, they stated, was a balanced and federal structure in which no one institution or individual could gain undue dominance. It was, therefore, a judicious application of the principles of republicanism.

The Federalists wisely concentrated their fire on three practical issues with broad appeal. The first was national security, which most people agreed was weak under the Articles. Under that instrument, advocates of the Constitution said that, though the Continental Congress could declare war, it could not procure enough money and men to wage it. Direct taxation was required in wartime to obtain sufficient revenue. The standing Army and Navy the Constitution authorized could protect the country from invasion, enhance its prestige, discourage foreign intervention, and perhaps offer an opportunity to drive the British out of the posts in the Great Lakes area as well as to thwart Spanish designs in the Southwest. Some Federalists related the foreign-debt problem to national security. They held that the debt was a potential source of conflict and might result in attacks on U.S. commerce unless Congress was assured steady revenue, as it would be under the Constitution.

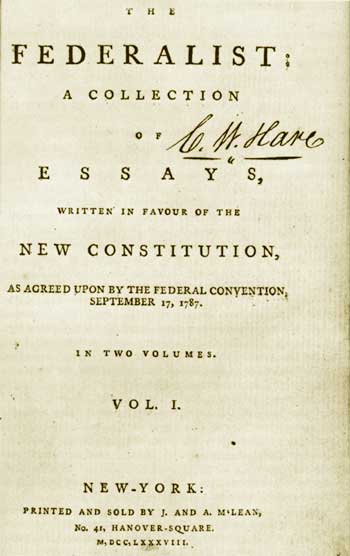

|

| In a series of anonymous newspaper essays during 1787-88, soon published in book form (1788) as The Federalist, Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay strongly advocated ratification of the Constitution. (Historical Society of Pennsylvania.) |

The second issue stressed by the Federalists was the bad economic situation, including the decline in shipbuilding and trade. They said this condition resulted primarily from the incapability of Congress to conclude favorable commercial treaties with other countries or to execute those it had negotiated. As a result, it was difficult to retaliate against foreign-trade restrictions, especially those of the British, or to arrange for American instead of British ships to carry goods.

The Federalists related both the national security and commerce issues to congressional ineffectiveness in meeting its treaty commitments. Unless Congress could help British merchants collect the prewar debts owed to them by Americans, the British could use that excuse to continue occupying the Great Lakes posts. And Britain would likely not agree to a commercial treaty until Congress had the power to speak for all the States.

Thirdly, the Federalists appealed to national pride. Referring to the insults inflicted on U.S. diplomats and appealing to the prevalent Anglophobia, they contended that the increased military power and governmental strength the Constitution afforded would enhance national prestige and elevate the United States in the eyes of other nations. If the document were not adopted, dissolution of the Union was likely and the States as independent entities would possess little power.

But perhaps the most simple and direct pleading of the Federalist cause was the letter Washington sent along with the Constitution when he submitted it to the Continental Congress. Its purpose, he wrote, was the "consolidation of our Union, in which is involved our prosperity, felicity, safety, perhaps our national existence."

Arguments were important, but the actual process of ratification involved practical politics.

|

|

http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/constitution/introh.htm

Last Updated: 29-Jul-2004