|

Geological Survey Bulletin 612

Guidebook of the Western United States: Part B |

ITINERARY

|

|

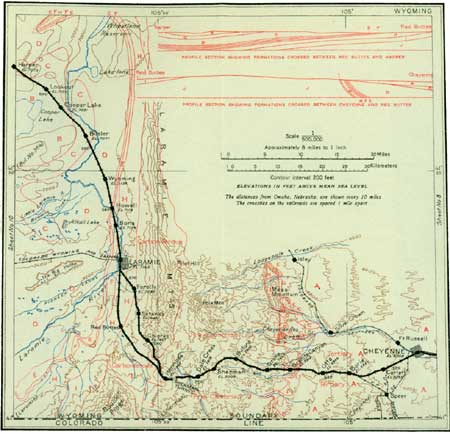

SHEET No. 9. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

|

Cheyenne. Elevation 6,058 feet. Population 11,320. Omaha 516 miles. |

The capital of Wyoming, Cheyenne (see sheet 9, p. 50), is 516 miles west of Omaha and nearly a mile higher. It is rich in memories of the "Wild West," memories which its inhabitants delight in perpetuating, for every year they hold one of the most picturesque gatherings in the country, known as "Frontier Days Celebration," at which Indians, cowboys, and plainsmen from all parts of the West, from Canada to Texas, gather for "bronco busting," steer tying, Indian dances, and the exhibition of all the unique and characteristic features of frontier life. And here gather from far and near spectators to see these performances.

Fort Russell, one of the larger Army posts, may be seen to the right, north of the railroad, as the train leaves Cheyenne. The city is supplied with water from reservoirs fed by springs that issue from the granite of the Laramie Mountains in Crow Creek canyon. Three miles east of the city the Union Pacific crosses the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad, and a mile west of it the train passes under the tracks of the Colorado & Southern. A little farther west, at Corlett, a branch turns south from the main line, running to Denver, where the westbound traveler can connect with the Denver & Rio Grande Railroad.1

1The branch from Cheyenne to Denver runs parallel with the Front Range of the Rocky Mountains, but at so great a distance that these mountains do not appear particularly impressive. It passes through a prosperous agricultural district in which are situated Eaton, Greeley, Brighten, and other towns. In this district the waters of the South Platte, the Thompson, the Cache la Poudre, and other smaller streams are diverted for irrigation, and from it great quantities of potatoes, beet sugar, canned fruits, vegetables, and farm and dairy products are shipped to market.

From Cheyenne the main line climbs a long, graded incline formed by the Arikaree beds, which extend far up the slope of the Laramie Mountains, where they abut against the foothills of the older sedimentary rocks or overlap the eroded edges of these rocks and the still older granite. (See fig. 7, p. 42.) The Arikaree and the underlying deposits were here probably tilted to some extent after deposition, but the large bowlders contained in them prove that the streams had a steep descent and were swift and powerful. The character of the Arikaree may be seen in the numerous cuts along the railroad and in the bordering bluffs of the valleys, which are plainly visible to the right, north of the incline. In these bluffs may be seen below the Arikaree the rocks of the Gering formation and of the White River group—the Brule clay and the Chadron formation—which contain fossil bones of Oligocene animals.2 The Brule clay may be distinguished from the train as long barren slopes just below the cliffs.

2The Oligocene epoch seems to have been one of relative quiescence compared with the Eocene, which was characterized by impressive volcanic activity and by the building of great mountain systems. The Oligocene formations are among the most widespread and most regularly distributed of the Tertiary formations of the Great Plains and cover a vast area in Nebraska and Wyoming. The sediments composing them were deposited by streams that meandered over low-lying plains and slowly built up the surface, much as the lower Mississippi is now building its delta or the Platte its flood plain, over which the train has just passed. Some of the old stream channels can be recognized by the filling of consolidated sand and gravel.

The plains country of Nebraska and eastern Wyoming was low during Oligocene time and the divides between the streams were not high enough to prevent flooding during high water. The whole country was virtually a great flood plain on which accumulated the sediments that the rivers brought from the mountains. With these sediments occur beds of pure volcanic ash, which must have been carried by the wind or floated by the streams for long distances. The volcanoes that had been so active in western America during the Eocene epoch had not ceased their eruptions—indeed they have not yet become entirely extinct, as is testified by the recent outburst of Lassen Peak, in northern California, although throughout later Tertiary and Quaternary time their fires have been gradually going out.

The lower Oligocene or Chadron formation is often called the Titanotherium beds because it contains bones of extinct mammals of that name. The titanotheres formed a comparatively short-lived family and seem to have been confined almost entirely to North America. Their remains are the most numerous and conspicuous fossils found in the lower Oligocene beds in western America. They were clumsy brutes of elephantine size having on the front of the skull a pair of great bony protuberances, which although hornlike in form were probably not sheathed in horn. (See Pl. VII, D, p. 41.) The head was long and large and of fantastic shape. In its thick heavy body and short, massive legs the titanothere resembled the modern rhinoceros. It was doubtless a sluggish, stupid beast, for its brain was small in comparison with the size of its body. The brain cavity was only a few inches in diameter and was surrounded by thick bone, as if to withstand shocks in battle. The titanotheres were the most formidable animals of the time, and though, so far as known, there were then no carnivores capable of doing them serious harm, yet they seem to have disappeared suddenly from North America. Their bones are not found in strata above a certain geologic horizon. The disappearance of a race of animals from any locality or even from the face of the earth does not necessarily require a long period of time. It is easily conceivable that the titanotheres were exterminated by some disease or that one of the physical changes which were so common in the West during Tertiary time made their life conditions here unfavorable and drove them to some other region, in which their remains have not yet been discovered.

The animals of Oligocene time seem to have been abundant as well as varied in kind. They had a somewhat more modern aspect than the animals that preceded them, for the processes of evolution had been active, and some of the primitive animals of Eocene time had developed into forms more nearly like those with which we are familiar now. Others seem to have left no descendants. Great numbers of Oligocene fossils have been found, and the life of the time is probably better known than that of any other epoch of the Tertiary period. Among the characteristic animals of this epoch were primitive forms of rhinoceroses, peccaries, ruminants, camels, insectivores, and opossums. Some of the creodonts or flesh eaters of Eocene time had developed into true carnivores, including many forms of both doglike and catlike animals. The saber-toothed cats which later developed into the saber-toothed tiger, one of the most formidable enemies of primitive man, first appeared in the Oligocene.

The horses whose history began with the diminutive four-toed Eohippus continued in the Oligocene where they are represented by many three-toed forms which were about as large as sheep. Hoglike animals were rather numerous, and although many of them were smaller than the modern swine some of them were very large. One of these, Archeotherium ingens (see Pl. VII, C, p. 41), was a formidable beast with curious protuberances on its head, the use of which is not known. Rhinoceroses similar to those now found in Africa and India lived in western America, and other rhinoceros-like animals known as anymodonts were abundant, but rhinoceroses did not reach their culmination in America until the Pleistocene epoch.

In addition to these animals of more modern appearance there were many that were so unlike anything now living that it is not possible to designate them by any common names. Among these are the animals of the protocerine group, of whose history little is known. They seem to have appeared suddenly in North America in Oligocene time and disappeared from this continent during the early part of the Miocene. They were deerlike creatures about the size of sheep. The head of the male was grotesquely ornamented with short bony protuberances and large scimitar-like tusks. Each front foot had four toes and each toe had a hoof like that of a deer or antelope. The supposed appearance of these curious animals is indicated in the restoration of one of the forms (Protoceras celer) reproduced in Plate VII, E.

The stations Corlett and Borie are passed between Cheyenne and Otto.

|

Otto. Elevation 6,946 feet. Omaha 530 miles. |

From several places near Otto station good views of the Front Range of the Rocky Mountains may be obtained to the left (south). Longs Peak is plainly visible, as well as the more massive and scarcely less elevated mountains north of it. Toward the right (north) the foothills east of the Laramie Range form conspicuous ridges that are plainly visible from the train. They consist of sedimentary rocks upturned to a nearly vertical position. These rocks range in age from Carboniferous to Cretaceous; the rocks of the most prominent ridge seen toward the north are those of the Casper formation and the less prominent ridges are formed by hard strata in the red beds of the Chugwater formation (Triassic or Permian) and by the rocks here called the Cloverly formation, the upper part of which may represent the Dakota sandstone of eastern Nebraska.1

1The table on page 41 shows the geologic formations exposed in the vicinity of the Laramie Mountains near the Union Pacific Railroad in the order of their age, the oldest at the bottom and the youngest at the top. The position of these formations in the complete geologic time scale may be ascertained by comparison with the table on p. 2.

Succession of the rock formations exposed along the Union Pacific Railroad east and west of the Laramie Mountains.

Period and

system.Epoch and series. Groups and formations. East of Laramie Mountains. West of Laramie Mountains. Tertiary. Pliocene. Ogalalla formation. Not represented. Miocene. Arikaree formation. Gering formation. Oligocene. White River group:

Brule clay.

Chadron formation.Tertiary (possibly including some Cretaceous). "Upper Laramie" formation. Cretaceous. Upper Cretaceous. Montana group:

Fox Hills sandstone.

Pierre shale.

Colorado group:

Niobrara limestone.

Benton shale, including Mowry shale."Lower Laramie" formation.

Montana group:

Lewis shale.

Mesaverde formation.

Steele shale.

Colorado group:

Niobrara limestone.

Beaten shale including Mowry shale.Lower Cretaceous. Cloverly formation. Cloverly formation. Jurassic or Cretaceous. Morrison formation. Morrison formation. Jurassic. Sundance formation. Sundance formation. Triassic or Permian. Chugwater formation. Chugwater formation. Carboniferous. Pennsylvanian. Casper formation. Forelle limestone.

Satanka shale.

Casper formation.Archean. Granite (including Sherman granite), gneiss, and schist. Granite (including Sherman granite), gneiss, and schist. The Tertiary sands and gravels of the ridge up which the train approaches the mountains form a thin covering over edges of older formations that range in age from Carboniferous to Cretaceous. The edges of the older formations are truncated—that is, the originally flat strata were tilted and their edges cut off obliquely by erosion before the Tertiary deposits were laid down upon them. Such a relation is called an angular unconformity. The attitude of these older rocks is known from exposures in the valleys both north and south of this ridge, and the relations are shown in the accompanying sketch section (fig. 7). The oldest sedimentary formation here is the Casper, consisting of gray to white limestone and red sandstone. Next is the Chugwater formation, which consists of red sandstone, red sandy shale, thin beds of limestone, anti thick beds of gypsum. Unconformably on this lies the Sundance formation, consisting of sandstone and shale and containing marine fossils that denote Jurassic age. This is followed with apparent conformity by the Morrison formation, which is noted for its huge fossil reptiles. Upon the Morrison, and apparently conformable with it, lies the Cloverly formation, consisting of two sandstones separated by shale. The upper sandstone is probably equivalent in age to the Dakota sandstone and is therefore the base of the Upper Cretaceous series. Above the Cloverly in conformable succession lie the Benton shale, the Niobrara limestone, the Pierre shale, and the Fox Hills sandstone.

FIGURE 7.—Tertiary sand and gravel overlying the truncated eroded edges of older rocks and forming the approach to the Laramie Mountains between Cheyenne and Granite Canyon utilized by the Union Pacific Railroad.

On reaching the foothills the train passes through a cut made in gray massive limestone and red quartzose sandstone of the Casper formation, which inclines steeply toward the east. Another aspect of this formation may be seen to the left (south) of the railroad, where it makes a steep cliff above the granite against which it is inclined. On Mesa Mountain, a flat-topped table-land which may be seen to the right, the Casper formation is nearly horizontal and forms the top of the mesa.

The limestone of the Casper formation at Granite Canyon furnished lime that was used by the railroad during the period of construction. This limestone is nearly pure calcium carbonate (98 per cent CaCO3), and on Horse Creek, 20 miles farther. north, about 55,000 tons is quarried every year to be burned for lime at the beet-sugar factories in eastern Colorado, where it is used in refining the sugar.

The ridge up which the train climbs in approaching the mountains is a remnant of the broad plain that once extended uniformly along the mountain front. The streams have made relatively little impression on the hard mountain rocks but have eroded away large parts of the soft Arikaree and other Tertiary beds of this plain, leaving the ridge as the one practicable route by which the railroad can ascend to the high table-land at the top of the Laramie Range.

This easy approach to the mountains was discovered in a peculiar manner. For more than two years engineers had searched in vain for a practicable grade by which the railroad might reach the summit of the range. On one of their excursions in the valley of Crow Creek they discovered Indians between them and their escort of mounted soldiers. In their attempt to find a point where the cavalry could see their signals for help the engineers reached the ridge, and in order to get to a place of safety they traveled down the ridge and found that it joined the plain east of the mountains without a break. This was just such a grade as they had been looking for, and further exploration showed that it was suitable for the road.

|

Granite Canyon. Elevation 7,312 feet. Omaha 535 miles. |

The station at Granite Canyon is built on granite porphyry, a crystalline rock of igneous origin. This particular granite porphyry is the oldest rock yet encountered on this route, being slope cut in the Brule clay, which lies directly on the granite porphyry. This is the westernmost exposure of this formation along the Union Pacific line. About 4 miles west of the Granite Canyon station, near Ozone, the road crosses a narrow strip of dark-colored granite gneiss, intruded ages ago into the older crystalline rock which constitutes the core of the Laramie Range.

|

Buford. Elevation 7,858 feet. Omaha 543 miles. |

From many points in the vicinity of Buford good views may be obtained of the high peaks of the Rocky Mountains far away to the left (south) and of the relatively low but rugged Sherman Mountains, a part of the Laramie Range, to the right. Two prominent points seen to the north are called Twin Mountains and are celebrated as one of the strongholds of the notorious desperado Slade.

At Buford is the quarry that has furnished ballast for the Union Pacific from Omaha to Rock Springs, Wyo., a distance of more than 800 miles. The quarry is in the crystalline rock of the Laramie Range, known as the Sherman granite.1 At Buford this granite has weathered to a depth of 50 feet or more. At the quarry the rock is loosened by heavy charges of explosive, which shatter it to small fragments, and it is then loaded on the cars by steam shovels. This quarry is said to have furnished about 10,000 carloads of ballast every year for the last 14 years and is still in active operation. Ballast is thus obtained at a cost of about 6 cents a ton, whereas the average cost of crushed rock used for railroad ballast is 49 cents.

1The Sherman granite forms a great mass intruded into older rocks in pre-Cambrian time. It is normally a coarse grained rock composed chiefly of pink feldspar, glassy-looking quartz, black hornblende, and mica, which in mass give it a spotted appearance. According to report it contains some gold at Buford but not enough for profitable extraction. It shows considerable variation in texture, color, and composition. One of the commonest varieties is coarsely porphyritic, the feldspar standing out in crystals 1 to 2 inches in length. Where the Union Pacific Railroad crosses Dale Creek, west of Sherman, the granite is rich in epidote, a green mineral, which together with the red feldspar imparts to it a mottled red and green color. Although hard when unaltered the Sherman granite breaks up readily into a coarse gravelly soil under the influence of heat, cold, and the action of water, so that it forms smooth, round hills. Where the rock is firm it weathers along widely spaced joints and forms heaps of rounded bowlders many of which may be seen from the train (Pl. VIII, A), particularly west of Buford.

|

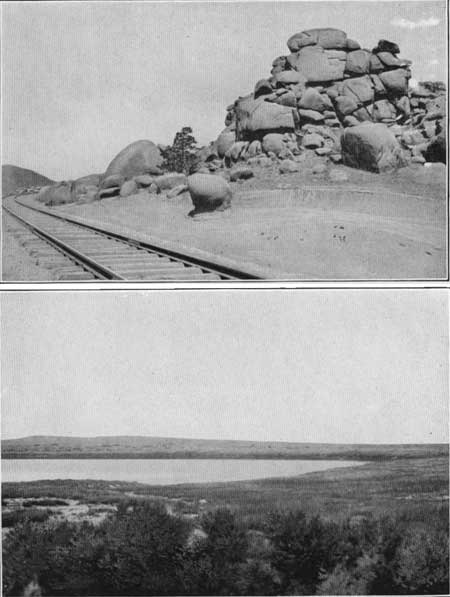

| PLATE VIII.—A (top), VIEW NEAR DALE CREEK STATION, WYO., SHOWING CHARACTERISTIC WEATHERING OF THE SHERMAN GRANITE. B (bottom), SMALL "SODA LAKE" ON THE PLAIN NEAR LARAMIE, WYO. The bed of the "lake," which contains water only in wet weather, is when dry covered with a white incrustation of salts, mostly alkali, left by the evaporation of water. |

|

Sherman. Elevation 8,009 feet. Population 115.* Omaha 547 miles. |

Sherman, so named in honor of Gen. W. T. Sherman, is the highest point on the Laramie Range reached by the railroad. It is claimed that from this point on a clear day may be seen Pikes Peak, about 165 miles, and Longs Peak, 60 miles to the south, and Elk Mountain, 100 miles to the west. The railroad was originally built a few miles north of its present location and crossed the divide at an altitude 237 feet higher than at present. On this old line a great stone monument was erected in honor of Hon. Oliver Ames and his brother Oakes, to whose energy and perseverance was largely due the construction of the Union Pacific Railroad.

The road here traverses the relatively flat summit of the Laramie Range, on what has been described as the Sherman peneplain.1 Along the track here and elsewhere in the Laramie Mountains there are numerous board fences or windbreaks. The snow drifts badly in the winter, and these fences prevent drifts from forming on the track.

1The uniform fineness and approximately uniform thickness of the Cretaceous sedimentary rocks on each side of the Laramie Range indicate that they once extended over the area now occupied by these mountains—in other words, that the mountains did not exist during Cretaceous time. At the close of that period the region was uplifted and the Cretaceous as well as the still older stratified rocks were steeply upturned on the eastern flank and slightly upturned on the western flank of the mountains. Then followed a long period of erosion during the Eocene epoch, when the sedimentary rocks were worn away from the top of the mountains, except where they were preserved by being infolded within the granite, and the crystalline rocks underlying them were eroded to a nearly level surface, or peneplain.

At the close of the Eocene epoch the range was again elevated and renewed erosion attacked this planed surface, deriving from it in part at least the material of the Oligocene and Miocene deposits that border the range on the east. These deposits could not all have been derived from this area, however, for in some places they extend over parts of this peneplain. The present irregularities of the plain were probably produced in large measure by late Tertiary or Quaternary erosion, which developed the canyons and removed large parts of the Oligocene and Miocene deposits.

|

Dale Creek. Elevation 7,918 feet. Omaha 550 miles. |

Dale Creek is a point on the new line that crosses Sherman Hill at a point 237 feet lower than the original crossing. This change not only saved the expense of climbing the heavy grades but did away with the famous Dale Creek Bridge, which was 650 feet long and 135 feet high. It also involved some notable feats in engineering. Along the new line there are many deep cuts in which the Sherman granite may be seen to advantage, and a tunnel is driven 1,800 feet through a spur of the same granite 3 miles west of Dale Creek. One hill near this creek, known as Gibraltar Cone, 100 feet high above the grade line, was drilled and loaded with about 1,000 kegs of black powder and 1,000 pounds of dynamite, and on July 4, 1900, this charge was exploded, blowing out the whole hill. The cuts are equaled by some of the great fills. The fill across Dale Creek is 900 feet long and 120 feet high in its deepest part, and 500,000 cubic yards of rock was used in constructing the embankment.

|

Hermosa. Elevation 7,862 feet. Omaha 554 miles. |

The name of the next station, Hermosa, which is Spanish for beautiful, seems appropriate, as may be realized by a glance to the left, toward the west. Across the broad Laramie Basin,1 which the road enters at this point, the mountains rise in rugged grandeur, and near by may be seen natural monuments carved from red sandstone in many forms. Some of these are illustrated in Plate IX.

1The Laramie Basin as usually defined is 90 miles long and 30 miles in maximum width and has a surface elevation of 7,000 to 7,500 feet. It is a hollow whose form is due to the general structure of the rocks that underlie it. It is overlooked by the Laramie Mountains on the east and the Medicine Bow Mountains on the west. These mountains are the northward continuation of the Rocky Mountain ranges of Colorado, the Laramie representing the Front Range and the Medicine Bow the north end of one of the inner ranges of the Rocky Mountains. The basin was formed by the warping and tilting of the rocks during the several periods of upheaval, and has later been modified by erosion. The Big Hollow, a depression in the general basin a few miles west of Laramie, is 9 miles long, 3 miles wide, and 200 feet deep. Other similar depressions are Big Basin, northwest of Laramie, Cooper Lake Basin, and many smaller hollows occupied by alkali lakes. The basin is partly drained by Laramie River, which crosses the Laramie Mountains through a deep ravine and finally joins North Platte River.

|

| PLATE IX.—NATURAL MONUMENTS ON THE PLAIN NEAR RED BUTTES, WYO., ERODED FROM RED SANDSTONE OF THE CASPER FORMATION. These monuments are 20 to 50 feet high. |

|

Red Buttes. Elevation 7,300 feet. Population 110.* Omaha 564 miles. |

From a point near Hermosa the road has two lines to Laramie. The westbound trains run by way of Red Buttes, and the eastbound trains come from Laramie over an easier grade by way of Forelle and Colores. Red Buttes is little more than a section house and takes its name from the natural monuments or buttes of red sandstone that are numerous in this vicinity (Pl. IX). From Hermosa to Red Buttes the route has lain on gently sloping red beds of Carboniferous age, consisting of the Casper formation, which was seen east of the mountains; the Satanka shale, made up of red shale and gypsum; and the Forelle limestone. These strata are overlain in some places by deposits of gravel, and at one place, a mile southeast of Red Buttes station, by gypsite. (For description see p. 48.)

About a mile south of Red Buttes is a deposit of gypsum, 20 or 30 feet thick, which is being manufactured into cement plaster or impure plaster of Paris. It is of the form known as rock gypsum and is a part of the Forelle formation. The most extensive gypsum deposits of this region occur at Red Mountain, 25 miles farther southwest.

Other natural products of commercial importance in this region are volcanic ash,1 bentonite,2 and soda.3

1Beds of volcanic ash occur about 4 miles south of Red Buttes. They are reminders of the volcanoes that were formerly so active in the Rocky Mountain region, but the location of the particular volcanoes that furnished this ash is not known. The material is pure white, soft, and fine grained. It occurs in beds that are comparatively young—that is, Tertiary or Quaternary. (See table on p. 2.) Volcanic ash is sometimes used as an abrasive, for scouring, polishing, or cleaning kitchen ware and other articles.

2About 6 miles west of Red Buttes, on the northwest shore of Creighton Lake, is a bed of bentonite, 3 or 4 feet thick; which appears as a white band in the black Benton shale, from which bentonite derives its name. Bentonite is a variety of clay used chiefly to give body and weight to paper, but to some extent in a dressing for inflamed hoofs of horses, in antiphlogistine (a proprietary remedial dressing), and as an adulterant of candies and drugs. It has notable powers of absorption, taking up about seven times its own volume of water. It absorbs twice as much glycerine as can be absorbed by diatomaceous earth, and for this reason has been suggested as a substitute for that material in the manufacture of dynamite. Other beds of bentonite occur farther west. It was first mined in this region in 1888, but with the closing of the western paper mills in 1905 its production practically stopped.

3Soda lakes occur near the Union Pacific line in Laramie Basin and at many places farther west. The waters of these lakes are strongly charged with sodium sulphate, and along their edges lie thick deposits of this salt that has been precipitated from the water, (See Pl. VIII, B, p. 44.) Three of these deposits were worked prior to 1895. The lakes lie in depressions in Cretaceous shale that contains a variety of salts, some of which were derived from the sea water in which the shale accumulated. Waters issuing as springs from this shale take the salts into solution, and rain falling on the surface of the shale dissolves them and carries them into the lakes. Water can escape from the depressions only by evaporation, so the salts accumulate in them. The soda deposits near Laramie have received more attention than any similar deposits in Wyoming. They cover about 60 acres, and the soda ranges in thickness from 1 foot to 16 feet.

|

Colores. Elevation 7,637 feet. Omaha 560 miles. |

On the track used by eastbound trains between Laramie and Hermosa is a station called Colores, from the highly colored rocks of the Carboniferous formations that are exposed near by. The eastbound trains pass over these red rocks for about 10 miles. The rocks contain water under pressure, and many large springs issue from them along the foothills. A spring near Colores furnishes water to fill a 4-inch pipe. Another spring east of Laramie furnishes the city supply—3,000,000 gallons a day. About 4 miles south of the city spring there is another large spring, which supplies a fish hatchery.

Toward the southwest, across the Laramie Basin, good views are obtained of the Medicine Bow Mountains, which constitute the north end of one of the main ranges of the southern Rocky Mountains and are so high that they are covered with snow during much of the year. Jelm Mountain, the nearest of this group, is a mass of ancient schist and granite gneiss brought up by faults and contains some minerals of special interest, among which are bismuth ores, allanite, and sperrylite.1

1Bismuth, which is used. extensively in the manufacture of drugs and of alloys that melt at low temperatures, occurs in Jelm Mountain in the form of carbonate and oxide. Sperrylite, or platinum arsenide (PtAs2), has been found at Centennial, near Jelm Mountain. It is very rare, and this is the only place where it occurs in quantity so large that serious attempts have been made to work it for platinum. At Albany, in this same region, is found allanite, a black mineral containing cerium, yttrium, thorium, and other rare elements. In some places the ore is nearly pure allanite; in others it contains numerous impurities. Cerium, which is now obtained as a by-product in the reduction of thorium from monazite, is alloyed with iron to make the "sparker" in the modern "flint and steel" mechanisms used as gas lighters. Cerium oxide is used sparingly in glass making to produce clear glass free from any greenish tint.

|

Laramie. Elevation 7,145 feet. Population 8,237. Omaha 573 miles. |

Laramie is the second city in population in Wyoming and is the center of large stock and manufacturing interests. The University of Wyoming, including the State Agricultural College, the School of Mines, the United States Experiment Station, the Wyoming State Normal School, the Wyoming State School of Music, and the University Preparatory School, is located here. The city, as well as the river, the mountain range, and the county, derives its name from Fort Laramie, which stands at the mouth of Laramie River. This most famous fort on the old Overland Trail was named directly or indirectly for Jacques La Ramie, a French fur trader of the early days. The old maps show the river as La Ramies Fork. Stansbury, Sublette, Bonneville, Parkman, and many others have described the old fort in its various stages from the small trading outpost of a fur company to a United States Army post.

Laramie was the home of Bill Nye, and here he founded the Boomerang, a journal of somewhat fitful existence, and wrote the articles for the Cheyenne and Denver papers that brought him into prominence as a humorist. It is worthy of notice that some 30 years ago Nye and James Whitcomb Riley published a railway guide. "What this country needs," they say, "is a railway guide which shall not be cursed by a plethora of facts or poisoned with information. In other railway guides pleasing fancy, poesy, and literary beauty have been throttled at the very threshold by a wild incontinence of facts, figures, and references to meal stations. For this reason a guide has been built at our own shops and on a new plan. It will not permit information to creep in and mar the reader's enjoyment of the scenery."

The city of Laramie rests on the red beds of the Chugwater formation, which may be seen at several places north of Red Buttes and are conspicuously exposed just north of the city. Cement plaster is manufactured from an impure gypsum known locally as gypsite,1 which occurs near the city. Pressed brick are made from the Benton shale for constructing buildings in the city and elsewhere.

1Gypsite is finely divided gypsum mixed with other matter, which does not interfere with its use for cement plaster. It is baked in ovens, its calcium sulphate remaining as a dry powder, which is mixed with water in plastering and then becomes hard.

Beyond Laramie is the station Bona.

|

Howell. Elevation 7,113 feet. Omaha 580 miles. |

The red beds of the Chugwater formation extend as far north of Laramie as Howell, although for most of this distance they are not visible, being covered with beds of gravel. West of Laramie is a low ridge where the Morrison (see pp. 41,42) and Cloverly formations are exposed. The railroad passes over them just north of Howell, but they are covered with surface debris and can not be seen from the train. About 2 miles north of Howell and also at Wyoming the traveler passes though deep cuts in the Benton shale.2

2The Benton formation in Nebraska consists of three members, two of shale and one of limestone, which are recognizable as far west as the east slope of the Laramie Mountains. West of the mountains the limestone is represented by shale indistinguishable from the other members. Near the base of the Benton on both sides of the mountains there is a hard sandy shale, called the Mowry, which weathers almost white and which contains numerous fish scales. Higher in the Benton is a sandstone, about 50 feet thick in the Laramie Basin, which seems to correspond to the Frontier formation of localities farther west. At some places indications of oil have been found in this sandstone.

In general there is no material difference in the Benton on opposite sides of the Laramie Mountains, either in physical character or in age, so that it is believed that when these beds were formed the Laramie Mountains did not exist and that the sea in which the sediments accumulated extended uninterruptedly over the area now occupied by the mountains. Some differences in nomenclature result from the fact that two standard geologic sections have come into use—one for the general region east of the mountains and the other for the region west of them. (See p. 41.) The Laramie Basin is in the transition zone between the two regions.

|

Wyoming. Elevation 7,138 feet. Population 194.* Omaha 584 miles. |

From Wyoming station the train passes northward over the Niobrara limestone, which, however, near the track is covered with beds of sand and gravel. Outcrops of it appear as light-colored bands southwest of the station on both sides of the river. Northwest of this station the road crosses a thick deposit of marine shale of middle Upper Cretaceous age, but the shale is here covered with the alluvial deposits of Laramie Valley.

At many places in this region during the summer there are large fields of gorgeously colored wild flowers. In some places the plain is colored red with the blossoms of a variety of loco weed, which is poisonous to horses, and in others large areas are covered with the deep-blue blossoms of the larkspur. Evening primroses are also abundant, but they seem to prefer the gravelly slopes at the side of the road.

For a few miles north of Laramie the train follows more or less closely Laramie River, here a placid meandering stream. Not many miles farther down its course, to the north, the river has cut squarely across the main Laramie Range, below which it flows out into the Great Plains country and empties into the North Platte. A large storage reservoir has been built near the mountains, and here the flood waters of the river are stored to irrigate the Wheatland tract, east of the mountains. This irrigation project was put though under the Carey Act by its author, ex-Senator Carey, later governor of Wyoming. Mr. Carey showed that he not only could draft a law but could operate under it, for the Wheatland project is said to be very successful.

|

Bosler. Elevation 7,077 feet. Population 264.* Omaha 592 miles. |

Just after crossing Laramie River, before reaching Bosler, the route leaves the marine Cretaceous shale and enters an area underlain by the sandstone of the Mesaverde, a coal-bearing formation of Upper Cretaceous age. The Mesaverde is of great economic importance west of the Rocky Mountains because it contains valuable beds of coal. This sandstone near Bosler is soft and has disintegrated so deeply that its character can not be readily discerned from the train. It is well exposed, however, at many places a little farther west.

|

Cooper Lake. Elevation 7,03l feet. Omaha 597 miles. |

Near the station of Cooper Lake a small alkali lake surrounded with white incrustations of sodium carbonate is visible near the track, but Cooper Lake itself can be seen only from a point several miles west of the station. This lake is about 4 miles long and 2 miles wide and occupies the lowest part of a broad depression. Like many of the smaller lakes of the Laramie Basin it has no outlet, and the considerable quantities of water entering it through the two creeks that head in the Medicine Bow Mountains to the south escape only by evaporation. For this reason the size of the lake is variable, depending on the balance between rainfall and evaporation.

|

Lookout. Elevation 7,120 feet. Omaha 600 miles. |

From Lookout station westward to Medicine Bow the railroad is relatively new. The road was originally built north of the line now operated, crossing Rock River about 10 miles northeast of the present crossing and following that river north of Como Bluff to Medicine Bow. The new route shortens the line 20 miles.

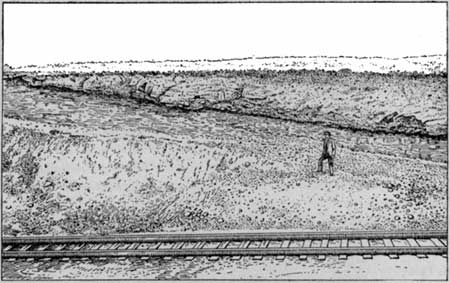

The station at Lookout is built on a sandstone that lies unconformably on the Mesaverde. About a mile west of the station this rock is exposed in railroad cuts and consists of soft yellow sandstone containing pebbles of quartz and other varieties of hard rock ranging from grains of sand to pebbles 2 inches in diameter. In a cut about 1-1/2 miles east of Harper this conglomeratic sandstone1 (see fig. 8) rests with uneven base—that is, unconformably—on a yellow shaly sandstone that contains marine shells.

1The conglomerate contains near the base sandstone concretions in which have been found fossil plants that seem to indicate Tertiary age, although these rocks have usually been regarded as a part of the Montana group of the Upper Cretaceous. These plants indicate that here, as elsewhere in this region, Tertiary beds lie unconformably on older rocks. The significance of this relation is discussed in the footnote on p. 2 and also in the footnote on p. 42. The conglomerate caps the hill south of Harper station, where it rests on rocks containing marine shells, but the contact is not easily determined owing to surface débris.

|

| FIGURE 8.—An unconformity in a railroad cut about 4 miles west of Lookout, Wyo., showing conglomeratic sandstone (A) of Tertiary age resting on marine shaly sandstone (B) of Cretaceous age. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

bul/612/sec12.htm

Last Updated: 28-Mar-2006