|

Geological Survey Bulletin 845

Guidebook of the Western United States: Part F. Southern Pacific Lines |

ITINERARY

|

|

SHEET No. 22 (click in image for an enlargement in a new window) |

MESCAL TO TUCSON, ARIZ.

|

Mescal. Elevation 4,064 feet. New Orleans 1,461 miles by north line, 1,490 miles by south line. |

At Mescal the north line (formerly the main Southern Pacific line from El Paso to Tucson) (pp. 131-162) is crossed by the south line (formerly the El Paso & Southwestern Railroad from El Paso to Tucson), which comes by way of Douglas (pp. 162-178). The two lines are closely parallel from Mescal nearly to Tucson, and practically the same features are to be observed over both lines. The tracks are now so connected by switches at Mescal that all westbound traffic, whether from Benson or Douglas, passes onto the north track; eastbound traffic comes to Mescal on the south track, trains for Douglas diverging just east of the station to the old El Paso & Southwestern tracks. Near Irene siding, 15 miles west of Mescal, the north track with its westbound traffic is bridged across the eastbound track and continues south of it into Tucson.

Desert conditions prevail all the way across southern Arizona, where the annual rainfall in the wide valleys is 10 inches or less. Most of the characteristic plants continue westward, notably the ubiquitous creosote bush, the mesquite, the yucca, the weird-looking ocotillo, and many cacti. On the adjoining mountains the rainfall is greater and there is a consequent difference in vegetation, and the higher summits carry extensive pine forests. The desert plants present many features of interest, especially in the flowering season, when some of them are of great beauty. On the lower rocky slopes grows the biznaga, or "barrel cactus" (Echinocactus wislizeni), with its large barrel-shaped body covered with curved thorns and bearing bright-red flowers in early summer. It contains much watery sap, which can be used to quench thirst very satisfactorily in case of necessity and has often been a life saver for man and beast. To obtain water the top is cut off and the liquid pressed out of the interior pulp, as shown in Plate 20, B. This pulp is also used in making candy. There are also the smaller Echinocactus johnsoni and clusters of the nigger-head cactus, E. polycephalus, which bears beautiful deep-red flowers in the early summer. All these cacti are covered with large spines and contain considerable water which is protected from evaporation by the thick skin of the plant. The desert rats, however, gnaw into some of them and clean out their watery pulp, leaving an empty shell. The yellow-looking, very spiny, branching cactus (mostly Opuntia fulgida) begins to be conspicuous in the region west of Mescal and is a prominent member of the desert flora all across southwestern Arizona.

Here also begins the sahuaro (Carnegiea gigantea), a treelike cactus with round fluted trunk which may reach a height of 50 feet; most of these strange plants bear branches that start high on the trunk and turn upward so as to produce the appearance of a giant candelabrum, as shown in Plate 31, B. The sahuaro is covered with thorns and in May bears at the top a cluster of white flowers, which in June develop into fruit that is in great favor with the Indians and birds. The Indians make from the fruit a kind of fig paste, also molasses, and an intoxicating drink. Garcés found the Indians greatly addicted to this drink at the time of his travels in 1775. Many birds make their nests in holes in the trunk, which they excavate in the soft pulpy material, but in a short time these cavities are sheathed with plant tissue which prevents sap leakage. It is stated by Spalding that most of these holes are made by the Gila woodpeckers Melanerpes uropygialis), but they are utilized by other species, such as the sparrow hawk, screech owl, purple marten, and flycatcher. To this giant cactus the elf owl (Micrathene whitneyi) resorts when breeding; it is the smallest of owls, only a little larger than the humming bird. The gilded flicker is also fond of the sahuaro and rarely found elsewhere. A woodpecker with a red head (male) and a black and white ladder-striped back so greatly prefers the branching cacti for its nest that it is called the cactus woodpecker (Dryobates scalaris cactophilus).

The sahuaro is a huge reservoir of water, made up of rods about an inch in diameter connected by plant tissue so that it has considerable strength to withstand the wind and also great capacity for rapid expansion when rain brings a supply of water. When dead the sahuaro loses its pulp, leaving a spectral skeleton of a bunch of tough wooden rods that burn with a bright flame; they are much used by the Indians for sheathing huts and making inclosures. The sahuaro prefers southward-facing slopes of rocky character where its roots can penetrate the soil between the rock fragments; basalt and tuff are favorable, but caliche appears not to be.

Members of the cactus family have remarkable ability to store water, because the roots extend widely, for the most part only a few inches below the surface, so as to absorb a quantity of water from the soil very quickly after a rain. It has been found by investigations by MacDougal, Spalding, and others at the Desert Botanical Laboratory at Tucson that once stored in the plant tissues, this water is retained with great tenacity as a provision for long, dry intervals. Water absorbed by plants is expended continuously in the process of living, mostly by evaporation through their green surface. While most of the cacti have leaves, as a rule these are minute or even microscopic (the conspicuous parts are botanically stems, not leaves), and the structure of their cells is such as to hinder transpiration and conserve the water stored. The slowness of chemical reactions in these and most other desert plants aid in the conservation of moisture. In the walls of the cells of the cacti are thin sievelike places which permit the easy passage of water from one cell to another throughout the interior. A barrel cactus was found to contain 96 per cent of water. A large sahuaro contains many gallons of water, sufficient to maintain it for a year or more. The water in some cacti is palatable, but that in others is very bitter, and it is interesting to note that those of the latter class are less protected by spines than those whose juice is acceptable. The spines of the cactus are straight or curved, hairy or feathery, and grouped in starry clusters or in rows. They have been used for fishhooks, needles, combs, and in various other ways by the primitive tribes. The flowers of the cactus vary in form, and most of them are beautiful in brilliant tints of purple, yellow, orange, and rose. (See pl. 31, A.) Some open by day; others, such as the night-blooming cereus, by night. Many of the species bear edible fruits, several of them delicious, and some of them yield seeds used by the Indians for food. In Arizona the cacti and some other desert plants are legally protected from removal, with a fine of $50 to $300 for each offense.

The maguey (mah-gay') (Agave parryi) and sotol (Dasylirion wheeleri) are scattered on many slopes, the former greatly preferring the rocky limestone areas. (See pl. 22, A.) Sometimes the maguey is called the "century plant," with the idea that it blossoms once in a hundred years, but the period is generally only six or seven years, and after the fruit is developed the plant dies. It is a useful plant to the Indians, who make tough fiber from its leaves. The bulbous base of its young staff when baked is like squash, and it also furnishes juice which when fermented becomes pulque (pool'kay) and when distilled yields the strong brandies "mescal" and "tequila" (tay-kee'la). Many piles of stones in the Southwest mark the sites of "mescal pits," where the plant was roasted by the Indians.

The broad stiff-leaved yuccas (Yucca macrocarpa and Y. baccata), called "dagger" or Spanish bayonet, bear large white flowers in bunches on a tall stalk, which develop into an edible fruit, "datil," somewhat like the pawpaw, that is utilized by the Indians. Their fiber is also used extensively for basket weaving. The abundant narrow-leaved yucca with its stalk of beautiful white blossoms (palmilla of the Mexicans) is called soap weed because its roots (called amole) make a soapy lather when pounded in water. Bear-grass (Nolina is a different plant but also contains an excellent fiber.

The more noticeable desert trees which grow in nearly all parts of western Arizona are the mesquite (Prosopis glandulosa), which often attains a height of 30 feet along the valleys, the palofierro, or iron-wood (Olnega tesota), and the paloverde (Cercidium and Parkinsonia), many of which grow to be more than 300 years old. There are a few chiriones, or soapberry trees (Sapindus marginatus), and desert willows (Chilopsis linearis) in the arroyos. The "Crucifixion" bush, consisting entirely of thorns, and the indigo thorn (Parosela spinosa) are interesting bushes of widespread occurrence. The very thorny catclaw, "uñas del gato" (Acacia greggii), merits its name, and there is another Acacia (constrieta) called "tisito," which bears globular yellow flowers of remarkable fragrance. On the higher lands are many junipers (sabinas), the piñon (Pinus edulis) with its delicious nuts, and many oaks.

Three miles west of Mescal, in the headwaters of Pantano Wash, there are outcrops and cuts in sandstone of Lower Cretaceous (Comanche) age that underlies the wide, low divide of the Mescal region, and farther west, notably near Pantano, there are scattered exposures of tilted conglomerates, sandstones with interbedded lavas, and Gila conglomerate (Pliocene and Pleistocene). A massive volcanic rock is exposed in the stream gorge about 80 feet deep just east of Irene, where the two tracks cross and where also the highway crosses the stream and railroad. Farther west, downstream, are exposures of agglomerate, a breccia or conglomerate of volcanic origin.

|

Pantano. Elevation 3,547 feet. Population 30.* New Orleans 1,472 miles. |

As the train approaches Marsh and Pantano sidings and from these places to Vail, there are seen to the south the Empire Mountains,35 culminating in Mount Fagan (elevation 6,175 feet). In these mountains there are many small mining prospects, mostly of silver ores; mines about Helvetia, on the western slope, have produced ore in moderate amount. This range extends south to the Santa Rita Mountains, in which there are several small mines, notably near Greaterville and Old Baldy. Some of the geologic relations are shown in Figure 46.

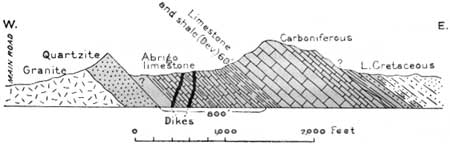

35In the various ridges of the Empire Mountains are exposed Bolsa quartzites Abrigo limestone, Martin and overlying Carboniferous limestones, sandstones and shales of Lower Cretaceous age, granites, and small areas of volcanic materials. The principal structural feature is an overthrust of a block of Carboniferous and Devonian limestone on pre-Cambrian granite that constitutes part of the summit and the northwestern slopes. To the southwest these limestones are overthrust onto Lower Cretaceous strata. Bolsa quartzite (Cambrian) is exposed in Davidson Canyon. The outer slopes of the mountains consist of sandstone, shale, and conglomerate of Lower Cretaceous age, which toward the east lie unconformably on the Paleozoic limestones, in places with a basal conglomerate consisting of pebbles and cobbles of various colored limestone, quartz, and other materials. This unconformity indicates a time break of many millions of years represented elsewhere by late Paleozoic, Mesozoic, and Jurassic strata.

|

| FIGURE 46.—Section 1 mile north of Helvetia mining camp, Ariz. |

|

Vail. Elevation 3,233 feet. New Orleans 1,480 miles. |

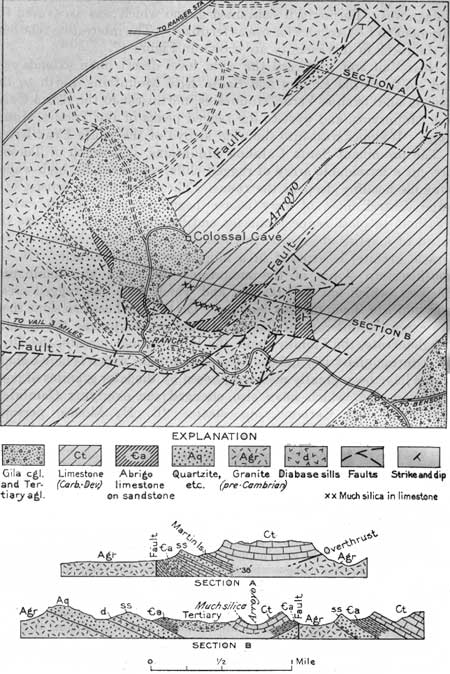

From points near Vail it may be seen that the Rincon Mountains merge into the Tanque Verde Mountains (tahn'kay vare'day), which in turn merge into the Santa Catalina Mountains, to the northwest. The ranges are separated by saddles, and each one has a prominent projection to the west. The prevailing rock in these ranges is a hard massive schist, but the Santa Catalina Mountains include toward the north a large mass of granite. On the west end of the Rincon Mountains Carboniferous limestone and other strata form foothill ridges which approach the railroad between Pantano and Vail.36 Three miles east of Vail, a cavern known as Colossal Cave extends far underground with many interesting galleries, some of them with stalactites and stalagmites. Formerly it contained guano which was excavated for shipment to Los Angeles for use as fertilizer. The interesting relations of the rocks in this vicinity are shown in Figure 47.

36The larger ridges consist of massive gray-blue limestone, Martin (Devonian) and Escabrosa (Mississippian), but in places this limestone is replaced by silica in large bodies which might easily be mistaken for quartzite. Under the Martin limestone is the Abrigo limestone, mostly very impure and sandy, carrying fragments of trilobites, lingulas, and other fossils characteristic of Upper Cambrian time. This is underlain by hard sandstone, which has been found by Stoyanow to contain Middle Cambrian fossils. Next below is hard reddish bedded quartzite with intrusive sills of diabase, which resembles the Dripping Spring quartzite of the Apache group. Under this is red shale like the Pioneer shale and at the base a conglomerate resembling the Scanlan conglomerate of the Apache group, lying on granite. The diabase closely resembles in character and relations the diabase in the Apache group farther north in Arizona. The beds are broken by many faults, and the higher limestones are pushed northeastward over the gneiss of the Rincon Mountains along the plane of a great overthrust. The movement on this thrust is measurable in miles. The thrust is well exposed on the northeast end of the larger limestone ridge, as shown in section A, Figure 47. Here the plane of displacement slopes to the southwest at a low angle. In this portion of the area a 38-foot bed of quartzite of unknown age overlies the Abrigo and apparently separates it from the Martin limestone, as in the Bisbee and Johnson areas.

|

| FIGURE 47.—Geologic map and cross sections in the vicinity of Colossal Cave, 3 miles east of Vail, Ariz. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Near Vail and westward the wide, level desert plain extends east and south to the Empire and Santa Rita Mountains, north to the Rincon and Tanque Verde Mountains, northwest to the Santa Catalina Mountains, and west to the ragged peaks of the Tucson Mountains. It slopes west into the wide arroyo of the Santa Cruz River.

The prominent Santa Catalina Mountains, just north of Tucson, present a formidable array of rugged cliffs, separated by high-walled canyons heading deep in the range. These mountains consist of a large central mass of very coarse pegmatite and granite, which weathers to picturesque pinnacles and balanced rocks; they are the latest of a series of granitic intrusions, one of which, known as the Oracle granite, is exposed in a large area around Oracle. On the southwestern slopes of the mountains the rocks are dominantly gneisses, which are well layered and which form the rugged crests and slopes of the numerous canyons. On the northeastern slope there are extensive outcrops of the Apache group, comprising the Scanlan conglomerate, the Pioneer shale, the Barnes conglomerate, the Dripping Spring quartzite, and the Mescal limestone, which is here a shale. These have been greatly metamorphosed by the later granites of post-Paleozoic age, which have also changed the overlying Cambrian, Devonian, and Carboniferous strata. (B. N. Moore, personal communication.)

It is believed that the steep southern and western sides of the Santa Catalina Mountains are determined by a great fault, for the strongly marked bedded structure of the schists dipping to the west is abruptly cut off on those sides, The upper part of the range appears to be the remains of an old erosion surface, now deeply dissected, on which the Mount Lemmon highland rises as a rounded swell, probably a residual mound. The northwest corner shows evidence of later upbending of 1,000 feet or more. (W. M. Davis.) Rising to the south foot of the mountains is a steep slope of sand and gravel underlain by sandstones and conglomerates of supposed late Tertiary age revealed in the deeper canyons. The beds dip steeply away from the mountain front and in places are considerably faulted. The high Tanque Verde and Rincon Mountains, east of Tucson, also consist of gneiss. All these mountains are included in a national forest, for their higher parts sustain a growth of valuable timber many live oaks and junipers occur from 4,500 to 6,000 feet, the yellow pine thrives between 6,000 and 8,000 feet, and there are small areas of fir and spruce above 8,000 feet. On the lower slopes sahuaros are numerous notably on the west slope of the Tanque Verde Mountains, 15 miles east of Tucson, where the State University has reserved an area in which these interesting plants are especially abundant and large.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

bul/845/sec22.htm

Last Updated: 16-Apr-2007